Abstract

Aims: Vasodilator-free basal stenosis resistance (BSR) equals fractional flow reserve (FFR) accuracy for ischaemia-inducing stenoses. Nonetheless, basal haemodynamic variability may impair BSR accuracy compared with hyperaemic stenosis resistance (HSR). We evaluated the influence of basal haemodynamic variability, as encountered in practice, on BSR accuracy versus HSR when derived from simultaneous pressure and flow velocity measurements, and determined its diagnostic performance for HSR-defined significant stenoses.

Methods and results: Simultaneous coronary pressure and flow velocity were obtained in 131 stenoses. The impact of basal haemodynamic conditions on BSR was evaluated by means of their relationship with the relative difference between BSR and HSR. Diagnostic performance of BSR, FFR, iFR, and resting Pd/Pa was assessed by comparing the area under the curve (AUC), using HSR as reference standard. The relative difference between BSR and HSR was not associated with basal heart rate, aortic pressure or rate pressure product. Among all stenoses, as well as within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range, BSR AUC was significantly greater than resting Pd/Pa and iFR AUC; all other AUCs were equivalent.

Conclusions: With simultaneous pressure and flow velocity measurements, basal conditions do not systematically limit BSR accuracy compared with HSR. Consequently, diagnostic performance of BSR is equivalent to FFR, and closely approximates HSR.

Introduction

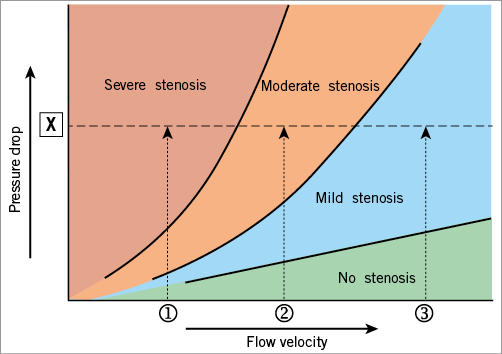

The haemodynamic consequences of a coronary stenosis are most adequately identified by the stenosis-specific relationship between the pressure drop across the stenosis and the flow (velocity) through it1-3. In the catheterisation laboratory, assessment of both coronary pressure and flow velocity allows the calculation of the hyperaemic stenosis resistance index (HSR), defined as the pressure drop across the stenosis divided by distal coronary flow velocity under hyperaemic conditions4. Such an index of stenosis resistance, as a summary of the stenosis-specific pressure drop – flow velocity relationship, “normalises” the pressure drop for the magnitude of flow at which it was obtained, and thereby might provide a more complete evaluation of the haemodynamic consequences of the stenosis than a pressure-only evaluation (Figure 1). Consequently, HSR was found to provide a notably high discriminative value for inducible ischaemia on myocardial perfusion imaging4.

Figure 1. Stenosis pressure drop – flow velocity relationship. The stenosis-specific pressure drop – flow velocity relationship implies that the pressure drop across a stenosis increases with increasing flow through the stenosis. Hence, a given pressure drop across a stenosis, X, may represent a stenosis severity ranging from mild to severe, depending on the flow velocity at which it was obtained, 1 to 3. The stenosis resistance index, defined as the ratio of the pressure drop across the stenosis to distal coronary flow velocity, “normalises” the pressure drop for the magnitude of flow at which it was obtained, providing a more objective assessment of haemodynamic stenosis severity, and allows the attribution of the measured pressure drop to stenosis severity 1, 2, or 3.

Since the pressure drop across a stenosis and distal flow velocity change in the same direction with altering coronary flow through the stenosis, the stenosis resistance index is less affected by the magnitude of flow at which it is calculated. This suggests that stenosis resistance assessment during basal conditions may provide a clinically useful measure of physiological stenosis severity. The concept of stenosis resistance calculated during basal conditions (basal stenosis resistance index [BSR]) recently demonstrated equivalent diagnostic accuracy for inducible myocardial ischaemia compared with current clinical standards, including FFR5. Nonetheless, BSR did not match its hyperaemic counterpart HSR perfectly in that study, which was attributed to the presumption that basal condition variability impairs the diagnostic accuracy of basal indices, and that hyperaemic conditions are required to reveal the flow-limiting potential of coronary stenosis adequately6.

For the ongoing development of BSR, the index should be validated in a contemporary data set outside of that in which it was developed, using currently available pressure-flow wires, and the influence of haemodynamic variability during the resting state must be assessed to see if it accounts for an impairment in diagnostic efficiency of BSR compared to HSR. Accordingly, in the present study we sought to evaluate whether the variability in basal haemodynamic conditions encountered in routine practice may explain potential differences between BSR and HSR, and how the diagnostic performance of BSR compares with other indices of stenosis severity, including FFR as the current standard of care, when assessed, for the first time, in a contemporary cohort of simultaneous pressure and flow velocity measurements.

Methods

DATA SOURCE

We included patients who were scheduled for coronary angiography or percutaneous coronary intervention at the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom. The sample from Amsterdam included 56 lesions, collected between November 2001 and January 2012. The sample from Imperial College London consisted of 75 stenoses, collected from 2010 to 2013. Exclusion criteria were restricted to significant valvular pathology, and prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery. The local ethical review boards approved the respective study protocols, and all subjects gave written informed consent.

CARDIAC CATHETERISATION AND HAEMODYNAMIC MEASUREMENTS

Cardiac catheterisation was performed according to standard clinical practice, and angiographic images were recorded in a manner suitable for quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) analysis. After diagnostic angiography, a 0.014-inch dual sensor-equipped guidewire (ComboWire®; Volcano Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to obtain simultaneous recordings of distal coronary pressure and flow velocity. Measurements were performed during basal conditions, as well as during hyperaemia induced by either intravenous infusion (140 µg/kg/min), or intracoronary bolus injection (20-60 µg) of adenosine.

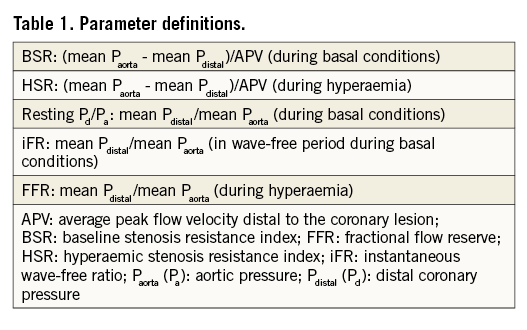

HAEMODYNAMIC DATA ANALYSIS

Data (ECG, coronary pressure and flow velocity) were extracted from a digital archive (ComboMap® [Volcano Corporation] or personal computer). Pressure drift was identified either by returning the pressure sensor to the catheter tip at the end of the procedure or by means of pressure drop-flow velocity curves, using the zero-flow pressure intercept as a measure of pressure drift. Haemodynamic data analysis was performed off-line using a custom software package written in MATLAB® (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The derived physiological indices were defined as depicted in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

First, the effect of aortic pressure, heart rate and rate pressure product during basal conditions on the difference between BSR and HSR was evaluated by testing their correlation with the relative difference between BSR and HSR7. Second, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed for BSR, iFR, FFR, and resting Pd/Pa using HSR as the physiological reference standard, in which HSR >0.80 mmHg/cm/s was considered physiologically significant4. ROC curves were compared by comparing the area under the ROC curves (AUC) using the method proposed by DeLong et al8. Additional ROC curves were constructed and comparison of AUCs was performed for stenoses within the clinically important 0.6 to 0.9 FFR range7. Within both cohorts, classification agreement of BSR, iFR, and FFR with the reference standard was evaluated at the respective predefined ischaemic cut-off values of 0.66 mmHg/cm/s for BSR5, 0.86 for iFR9, and 0.75 for FFR10, and was compared by means of McNemar’s test of symmetry.

Data are presented as mean (±standard deviation) or median (1st and 3rd quartiles [Q1, Q3]). Comparison was performed by Student’s t-test, or the chi-square test, as appropriate. A p-value below the two-sided α-level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PATIENTS

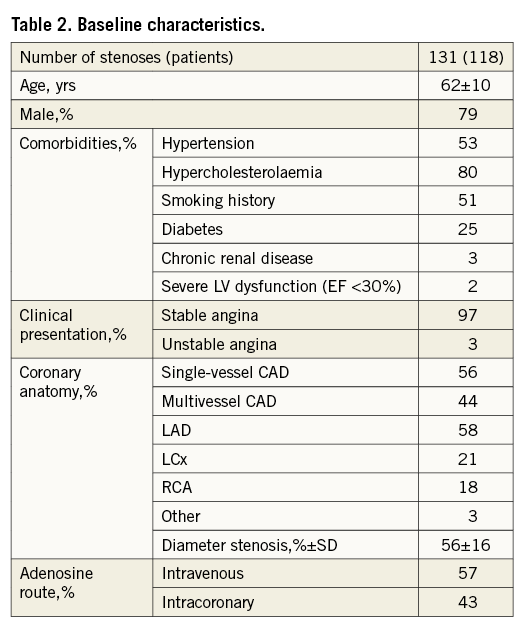

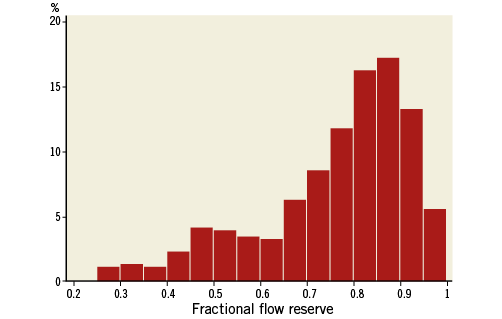

In 118 patients, a total of 131 coronary stenoses were evaluated by means of simultaneous coronary pressure and flow velocity measurements. Demographics and angiographic stenosis characteristics are summarised in Table 2. Stenosis severity distribution by FFR is depicted in Figure 2, showing a preponderance of stenoses (57.3%) that fell within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range. Hyperaemia was induced by means of intravenous (IV) adenosine in 57% of stenoses, while an intracoronary (IC) bolus injection of adenosine was used in the remaining 43% of stenoses.

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of fractional flow reserve values across the study population.

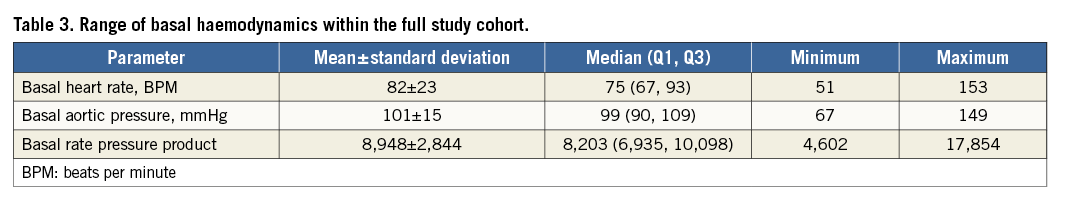

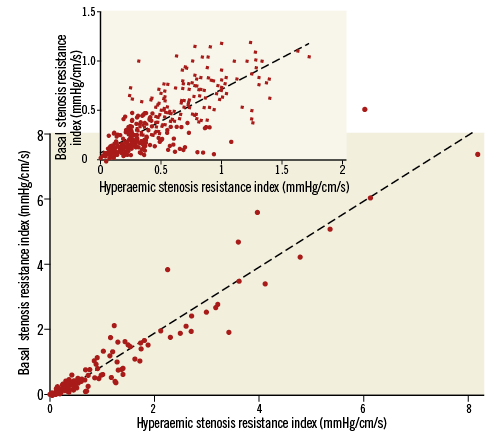

The ranges of basal haemodynamics in this study population are depicted in Table 3. Across all stenoses, BSR was linearly related to HSR (R=0.95 [R2=0.90], p<0.001) (Figure 3). The relative difference of BSR compared with HSR (BSR – HSR/HSR) was not associated with heart rate (R2=0.003, p=0.546), mean aortic pressure (R2=0.000, p=0.894) or rate pressure product (R2=0.009, p=0.288) during basal conditions.

Figure 3. Relationship of basal stenosis resistance index (BSR) to hyperaemic stenosis resistance index (HSR). The inset depicts the relationship of BSR to HSR within the relevant range of BSR values <1.2 mmHg/cm/s.

DIAGNOSTIC PERFORMANCE AGAINST HSR

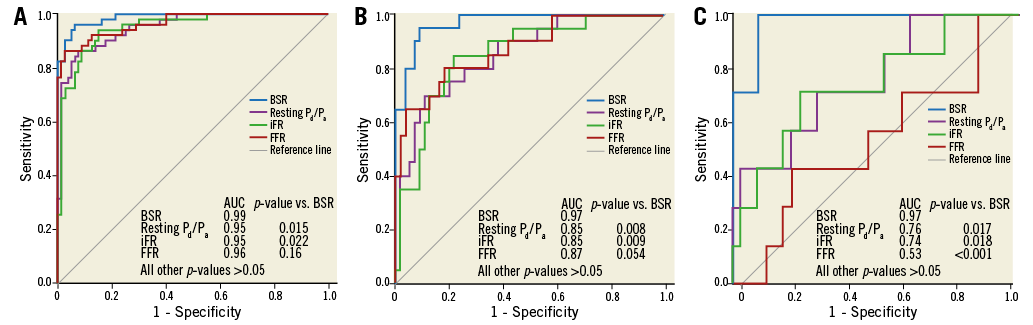

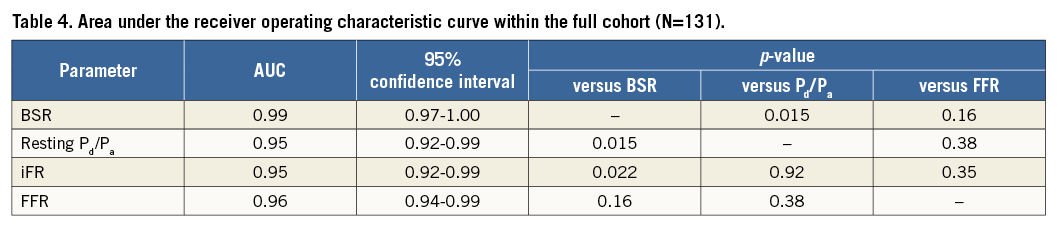

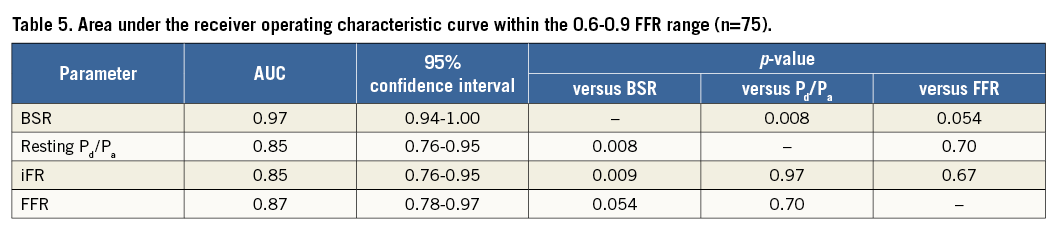

ROC curve analysis for HSR-identified physiologically significant coronary stenoses yielded an excellent AUC for BSR, iFR and FFR (Figure 4A, Table 4). The numerically higher AUC for BSR compared with FFR did not reach statistical significance (p=0.155). Notably, the AUC of BSR was significantly higher than the AUC of resting Pd/Pa, and also significantly higher than the AUC of iFR (p=0.015, and p=0.022, respectively), while the numerical difference in AUC between FFR and resting Pd/Pa or iFR did not reach statistical significance (p=0.38, and p=0.35, respectively).

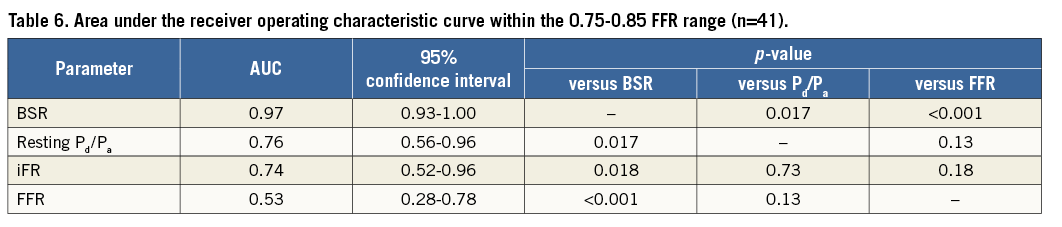

Figure 4. Receiver operating characteristic curves against the hyperaemic stenosis resistance index as the reference standard. A) Within the full study cohort. B) Within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range. C) Within the 0.75-0.85 FFR range. P-values for the comparisons with BSR are indicated; all other p-values >0.05 (Table 4-Table 6).

Of all coronary stenoses, 57.3% fell in the 0.6-0.9 FFR range. Within this clinically important range, the AUC of BSR was significantly greater than that of iFR and resting Pd/Pa (Figure 4B, Table 5), and was numerically greater than the AUC of FFR, with a trend towards statistical significance (p=0.054) (Figure 4B, Table 5). The AUC of FFR was equivalent to that of iFR, and resting Pd/Pa (p=0.67, and p=0.70, respectively). These findings were emphasised for stenoses in the 0.75-0.85 FFR range (41 stenoses in this data set), where the AUC of BSR was significantly greater than the AUC of FFR, iFR and resting Pd/Pa (p<0.02 for all comparisons with BSR) (Figure 4C, Table 6). Notably, in this FFR range, HSR was normal in 34 (83%), and abnormal in 7 (17%). The findings for BSR were similar: BSR was normal in 35 (85%), and abnormal in 6 (15%) of these stenoses. For stenoses in the 0.81-0.85 FFR range (31 stenoses in this data set), HSR was normal in 27 (87%), and abnormal in 4 (13%). Findings for BSR were equal, with normal BSR in 27 (87%), and abnormal BSR in 4 (13%) cases.

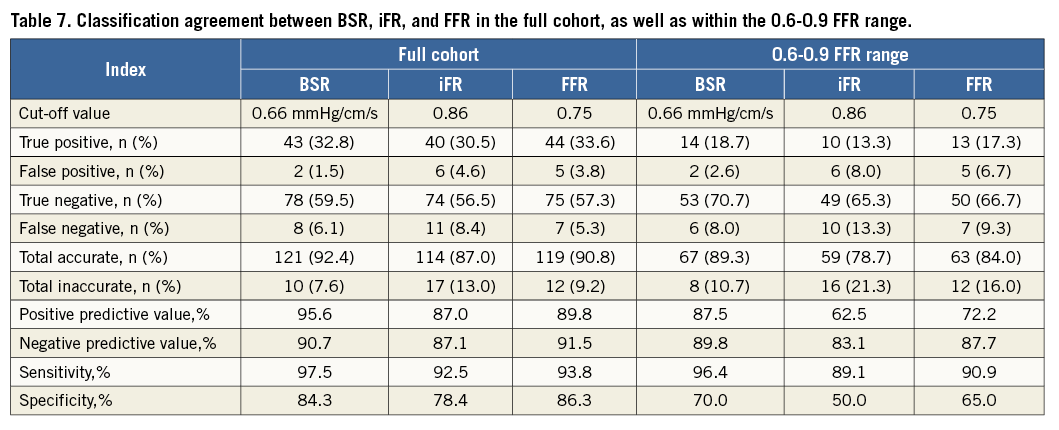

Classification agreement with the reference standard was higher for BSR than for FFR or iFR, both in the full cohort (92.4% for BSR versus 87.0% for iFR, and 90.8% for FFR; Table 7, left panel), as well as within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range (89.3% for BSR versus 78.7% for iFR, and 84.0% for FFR; Table 7, right panel). However, these numerical differences did not reach statistical significance (p>0.05 for all), although the difference in classification agreement between BSR and iFR within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range showed a trend towards statistical significance (p=0.057).

Discordance in stenosis classification between BSR and HSR occurred in 7.6% of stenoses (10 out of 131). In the eight cases where BSR was ≤0.66 mmHg/cm/s while HSR was >0.80 mmHg/cm/s, BSR and HSR agreed with coronary flow velocity reserve (CFVR) in 50% of cases. Moreover, in the two cases where BSR was >0.66 mmHg/cm/s while HSR was ≤0.80 mmHg/cm/s, BSR agreed with CFVR in both cases.

Discussion

We observed that variations in basal haemodynamic conditions as encountered in routine clinical practice do not systematically lead to differences between BSR and its hyperaemic counterpart, HSR, and that, when derived from simultaneous coronary pressure and flow velocity measurements, BSR agrees very closely with HSR both in terms of a linear relationship between the two parameters, and in terms of stenosis classification. Moreover, the discriminative power of BSR is at least equivalent to that of FFR across the complete range of coronary stenosis severities, and BSR yields a numerically greater discriminative power compared with FFR within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range, showing a trend towards statistical significance. Finally, the simultaneous assessment of both pressure and flow during basal conditions provides a significant increment in discriminative value compared with basal pressure-only evaluation.

Our observations support the fundamental proposition that basal conditions allow accurate assessment of functional stenosis severity, and that BSR can equal hyperaemic indices in terms of diagnostic performance. Moreover, our results suggest that simultaneous assessment of pressure and flow velocity may provide important diagnostic advantages when stenosis discrimination is most challenging, when physiological stenosis severity is within the intermediate FFR range or clusters around the cut-off, even in the absence of a hyperaemic state.

PHYSIOLOGICAL VARIATIONS IN BASAL VERSUS HYPERAEMIC HAEMODYNAMICS

It has been argued that basal conditions do not allow functional stenosis severity assessment for two main reasons: 1) because it was assumed that haemodynamic variability is more extensive in basal conditions compared with hyperaemic conditions, impairing the diagnostic accuracy of basal indices6, and 2) because flow velocity at rest is assumed to be insufficient to allow discrimination of functionally significant from functionally non-significant coronary stenoses, particularly in coronary stenoses of intermediate physiological severity, i.e., within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range7.

In our study population, we observed that there was a strong correlation between absolute BSR and HSR values, and that the relative difference between BSR and HSR was not associated with heart rate, aortic pressure or rate pressure product during basal conditions. This implies that variations in basal haemodynamic conditions as encountered in routine clinical practice do not systematically lead to differences between BSR and its hyperaemic counterpart, HSR, and indicates that BSR is not susceptible to variations in heart rate and blood pressure during resting conditions. As such, our data support the hypothesis that the technical limitations of separate assessment of pressure and flow velocity data for the calculation of BSR have limited its accuracy in comparison with HSR, as will be discussed below.

Our results further confirm that resting flow does allow accurate discrimination of functionally significant from functionally non-significant coronary stenoses. BSR yielded a notably high discriminative power against HSR, with an AUC closely approximating 1.0. This equivalence was maintained within the intermediate 0.6-0.9 FFR range. Moreover, dichotomous agreement of BSR with HSR was excellent, even in stenoses within the intermediate FFR zone, and in those close to the FFR cut-off value. Hence, our data add to the accumulating evidence suggesting that resting conditions allow adequate stenosis discrimination, even within the challenging intermediate 0.6-0.9 FFR range, if combined pressure and flow assessment is utilised to maximise the discriminative power provided by resting conditions.

THE PERTINENCE OF SIMULTANEOUS PRESSURE AND FLOW VELOCITY MEASUREMENTS FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF BSR

In the BSR validation study, HSR was found to yield significantly higher discriminative value for inducible myocardial ischaemia compared with BSR5. It is important to acknowledge that, in that study, BSR was determined from intracoronary haemodynamic data obtained by means of two separate sensor-equipped guidewires: coronary flow was measured subsequent to coronary pressure. This methodology by definition limits the fundamental advantages of combining pressure and flow velocity in a single index, as it partly dissipates the intrinsic relationship between the pressure drop across a stenosis and flow velocity. Because physiological variations in coronary pressure and flow velocity - secondary to haemodynamic perturbations resulting, for example, from changes in heart rate or blood pressure - are not optimally accounted for when pressure and flow are not simultaneously obtained, and such variation is by definition most pertinent in basal low-flow, low-pressure drop conditions, this methodological limitation most likely affects the diagnostic accuracy of BSR more than that of HSR. Therefore, the difference in discriminative power between BSR and HSR identified previously may particularly be explained by the absence of simultaneously obtained intracoronary pressure and flow velocity data. Consequently, we observed that, when measured with a dual sensor-equipped guidewire, allowing simultaneous assessment of coronary pressure and flow velocity11, BSR yields an excellent discriminative value for HSR-identified physiological coronary stenosis severity.

DISCRIMINATIVE POWER OF COMBINED PRESSURE AND FLOW, COMPARED WITH PRESSURE-ONLY

Despite the fact that the discriminative power of BSR, and FFR for HSR-identified physiologically significant stenoses was high across the full range of stenosis severities, a pertinent drop in discriminative power was noted for FFR within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range. It is especially this range of FFR values that is considered most challenging in terms of stenosis discrimination7. Within the 0.6 to 0.9 FFR range, excluding lesions in which agreement between all parameters may be expected a priori12,13, there was a trend towards a superior discriminative power of BSR over FFR (BSR AUC: 0.97 vs. FFR AUC: 0.87, p=0.054). Moreover, 65% and 74% of stenoses in the FFR grey zone would be reclassified by HSR or BSR, respectively, and 13% of stenoses with a negative FFR close to the cut-off value would be reclassified by either HSR or BSR. These observations may explain the incremental discriminative power previously documented for HSR over FFR for identification of stenosis-related inducible myocardial ischaemia4,5, despite a high concurrence across the full range of stenosis severities. This diagnostic advantage probably derives from the fact that BSR and HSR directly measure flow instead of estimating it from coronary pressure. This advantage seems important considering the fundamental importance of coronary flow in myocardial function and ischaemia14, recent observational data suggesting that measurement of flow significantly enriches the diagnostic and prognostic information derived from coronary pressure measurements15,16, and the documented incremental prognostic value of HSR over FFR in stenoses of intermediate physiological severity17.

The observations in the present study suggest that simultaneous measurement of coronary pressure and flow velocity may provide the most efficient discrimination of physiologically significant from physiologically non-significant coronary stenoses, even in the absence of a hyperaemic state. Nonetheless, although conceivable, it remains to be elucidated whether these differences translate into pertinent differences in clinical outcomes.

PRESSURE-ONLY VERSUS COMBINED ASSESSMENT OF PRESSURE AND FLOW VELOCITY: CLINICAL PRACTICE

Despite the fact that our results point in the direction of an improved diagnostic efficiency by measuring both intracoronary pressure and flow velocity, even in the absence of a hyperaemic state, there is an important practical consideration currently favouring pressure-only physiological assessment of coronary stenosis severity in clinical practice. Doppler flow velocity measurements are relatively difficult to obtain when compared with pressure measurements, and reliable assessment of Doppler signals currently depends on operator experience with this specific tool. Moreover, wire characteristics of contemporary dual sensor-equipped guidewires are vastly less favourable as compared to workhorse guidewires, complicating physiological assessment with this armamentarium. Therefore, technical advances with respect to dual sensor-equipped guidewires are required to facilitate widespread clinical adoption of advanced physiology techniques, such as indices of stenosis resistance.

Considering the rigorously documented feasibility and clinical potential of coronary pressure measurements in daily practice, it is important to note that both across the full range of FFR values, as well as within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range, iFR was equivalent to FFR in terms of discriminative power, as well as classification agreement with the reference standard. In accordance with previous studies, the diagnostic accuracy of resting Pd/Pa was equivalent to iFR and FFR as well. Our study confirms the findings in smaller studies that the diagnostic efficiency of iFR for identification of physiologically significant coronary stenoses equals that of FFR across the whole range of lesion severities, as well as within the 0.6-0.9 FFR range18,19. These data further support the clinical applicability of iFR as a vasodilator-free alternative for FFR, while awaiting further technical improvements of combined pressure/flow measurements to support the clinical feasibility of derived parameters, such as BSR.

Limitations

Considering the retrospective nature of the data, this study should be considered proof of concept, and should be interpreted in the light of several limitations. The data presented were predominantly obtained in stable patients. As such, our findings cannot be extrapolated to patients with acute coronary syndromes. Assessment of intracoronary flow velocity is sensitive to technical failures, and its accurate measurement depends on operator experience, which limits the practical applicability of currently available Doppler flow systems. All measurements in this study were performed by operators with ample experience in intracoronary flow velocity measurements. It must be noted that no gold standard for stenosis-specific inducible myocardial ischaemia is available to date. With this limitation borne in mind, we used HSR as the physiological reference standard in the present study, an approach governed by the well-documented value of the stenosis-specific relationship between coronary pressure and flow velocity, as well as the understanding that HSR is least susceptible to variability in hyperaemic conditions and has a high specificity for inducible myocardial ischaemia4,17,20.

Our current observations indicate that haemodynamic variability during basal conditions as encountered in routine clinical practice does not systematically lead to differences between BSR and its hyperaemic counterpart, HSR. However, in contrast to other studies, no pharmacological perturbation of haemodynamics was performed in the present study. Nonetheless, since pharmacological perturbation of haemodynamics is not routinely performed in the assessment of physiological stenosis severity, our findings on the influence of haemodynamic variability in the magnitude encountered in clinical practice support the conclusion that basal conditions allow the assessment of physiological stenosis severity by means of BSR.

Different adenosine routes (both intravenous and intracoronary) and doses were used to induce hyperaemia. Although this might be seen as a potential limitation, it better reflects the real-world utilisation of FFR. Although larger doses of intracoronary adenosine can be used, the dose used in this study (20-60 mcg) adheres to the doses used in the clinical validation of FFR, and achieves FFR values equivalent to 140 mcg/kg/min of intravenous adenosine infusion, as was recently discussed in detail21. Moreover, FFR determined with low-dose intracoronary bolus administration of adenosine has been shown to provide similar clinical benefits compared with FFR determined with intravenous infusion of adenosine22.

Conclusion

We documented that the discriminative power of BSR was substantially equivalent to that of FFR when simultaneous pressure and flow assessment is performed to maximise the discriminative power provided by resting conditions. Nonetheless, due to practical limitations, ongoing technical advances are awaited for optimal identification of the potential of simultaneous pressure and flow velocity measurements in clinical practice.

| Impact on daily practice Since the worldwide adoption of FFR remains low, a vasodilator-free approach using basal stenosis resistance index may provide an opportunity to facilitate a more widespread adoption of physiologically guided coronary revascularisation in clinical practice, and circumvent any uncertainties and ambiguities associated with the dosing and administration of adenosine. The present study supports the superior diagnostic accuracy of BSR over pressure-only resting physiological indices and documents the close agreement of BSR with the hyperaemic stenosis resistance index (HSR), as long as contemporary dual sensor-equipped guidewires are used for its assessment. |

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the nursing staff of the cardiac catheterisation laboratory of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (Head: M.G.H. Meesterman), and of Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, for their skilled assistance.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 224495 (euHeart project), and by grants from the Dutch Heart Foundation (2006B186, 2000.090, and D96.020). S. Sen (G1000357) and S. Nijjer (G1100443) are Medical Research Council fellows. J.E. Davies (FS/05/006) and R. Petraco (FS/11/46/28861) are British Heart Foundation fellows.

Conflict of interest statement

J. Davies is a consultant for Volcano Corporation, and holds licensed patents pertaining to the iFR technology. T. van de Hoef, M. Echavarria-Pinto, J. Escaned, and J. Piek have served as speakers at educational events organised by St. Jude Medical and Volcano Corporation. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.