Abstract

Aims: In the absence of randomised data, we aimed to compare the transapical ACURATE and transfemoral ACURATE neo with the SAPIEN 3 prosthesis using propensity matching.

Methods and results: From 2012 to 2016, 1,306 patients at three German centres received either the ACURATE/ACURATE neo prosthesis (n=591) or the SAPIEN 3 prosthesis (n=715). Through nearest neighbour matching with exact allocation for access route and centre, pairs of 329 patients (250 transfemoral, 79 transapical) per group were determined. Patients were 81 years old on average and had a logistic EuroSCORE I of 19%. Predilatation and post-dilatation were more frequent in the ACURATE group (97.6% versus 52.1%, p<0.001 for predilatation and 40.4% versus 11.6%, p<0.001 for post-dilatation), but rapid pacing for implantation was used less frequently (37.1% versus 98.2%, p<0.001). More-than-mild aortic regurgitation at postoperative echocardiography was 12.0% for the ACURATE group and 3.1% for the SAPIEN group, p≤0.001). More-than-mild aortic regurgitation in the ACURATE group differed amongst the centres with 6.0% (3/50) in centre A, 34.1% (29/85) in centre B and 3.4% (6/181) in centre C. Patients in the ACURATE group less frequently had pacemaker implantation compared to the SAPIEN 3 group (11.9% versus 18.5%, p=0.020), 30-day mortality was 4.6% versus 2.1%, respectively, p=0.134, and one-year survival was 83.1% (95% CI: 77.6-87.4) versus 88.8% (95% CI: 84.0-92.2).

Conclusions: In this propensity score analysis, patients treated with the transapical ACURATE or transfemoral ACURATE neo prosthesis less frequently had pacemakers at 30 days but had more aortic regurgitation and lower one-year survival.

Introduction

Numerous randomised controlled trials have been conducted to compare outcomes between surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)1. With increasing use of TAVI1,2,3, refined techniques and devices, it is now paramount to compare devices in randomised controlled trials to identify the best device for the individual patient.

To date, only a few randomised controlled trials are available. The CHOICE study randomised patients to the self-expanding CoreValve® prosthesis (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) versus the SAPIEN XT (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) and found statistically lower device success and higher pacemaker rates in the self-expanding group4. The recently published REPRISE III study randomised patients to the mechanically expandable Lotus™ prosthesis (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) and to a self-expanding prosthesis and found non-inferiority to the CoreValve® and CoreValve® Evolut™ R (Medtronic) prostheses for the primary safety endpoint and superiority for the primary efficacy endpoint5.

To the best of our knowledge, no randomised data are available comparing the transapical ACURATE TA, the transfemoral ACURATE neo™ (Symetis, a Boston Scientific company, Ecublens, Switzerland), and the SAPIEN 3 (Edwards Lifesciences) prostheses. In the absence of randomised data, we aimed to provide further clinical evidence using a propensity-matched comparison of the transapical ACURATE TA and the transfemoral ACURATE neo with the SAPIEN 3 prosthesis.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND PATIENT SELECTION

Retrospective data collection of patients treated for aortic stenosis was conducted at three centres in Germany from 2012 to 2016. Treatment and patient follow-up were according to the standard of care at the respective hospitals. No core laboratory or clinical events committee was used; however, all clinical events were categorised by one study physician and the degree of calcification was assessed by two study physicians.

The self-expanding transapical ACURATE TA and transfemoral ACURATE neo systems, as well as the transfemoral and transapical balloon-expandable SAPIEN 3 system, have been described previously6,7,8. Endpoints including mortality are classified according to VARC-2 criteria.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

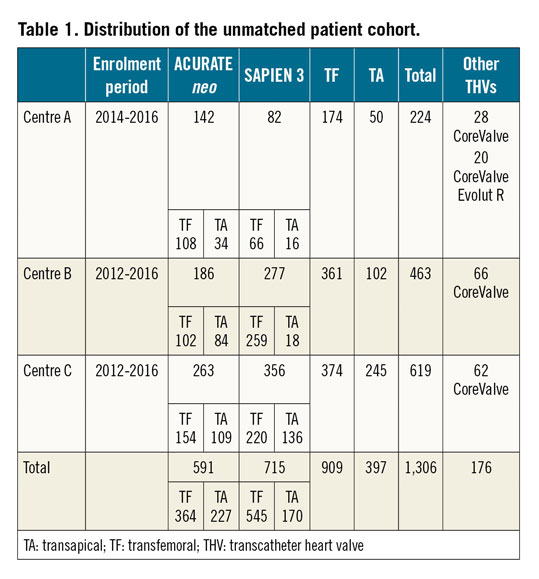

The unpaired patient population included all patients in whom an implant was attempted. Figure 1 shows the variables used for the propensity-score analysis. The estimation was performed with logistic regression analysis. The variables centre and access route were exactly matched. Calculated score estimates with callipers of 0.2 (x standard deviation of the logit of the estimated propensity score) were used for matching. The algorithm was the greedy nearest neighbour matching method.

The follow-up time was calculated from procedure date to the last available subject information. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages of the total and continuous variables as mean±SD. Confidence intervals were calculated when appropriate. The unmatched groups were compared using Pearson’s chi-square and one-way ANOVA. Matched groups were compared using the Wilcoxon and McNemar tests and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis using the log-rank test. The hazard ratio was calculated with Cox logistic regression. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, Version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

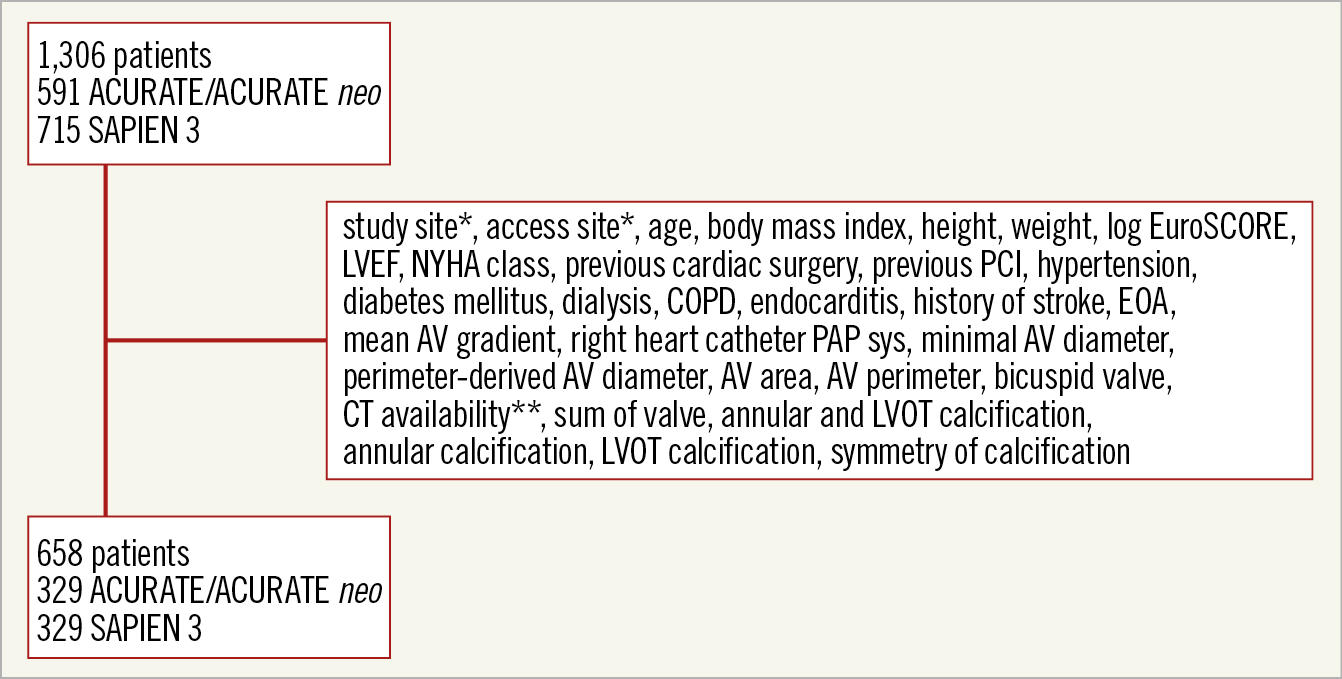

We retrospectively collected data at three German centres from the date of the first use of the transapical ACURATE and transfemoral ACURATE neo prostheses at the respective centres until 2016. Centre and access route details of the unmatched population are provided in Table 1, which also includes other transcatheter heart valves implanted during the same time period. Of the 1,306 patients in the unmatched cohort, 658 patients remained after propensity matching (Figure 1). There was an exact match for centre (57 patients in each group in centre A, 90 in centre B, and 182 in centre C) and access route (250 transfemoral and 79 transapical patients in each group).

Figure 1. Propensity matching. *exact match. ** only patients with available CT scans were included in the analysis. AV: aortic valve; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT: computed tomography; EOA: effective orifice area; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; PAP sys: systolic pulmonary artery pressure; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

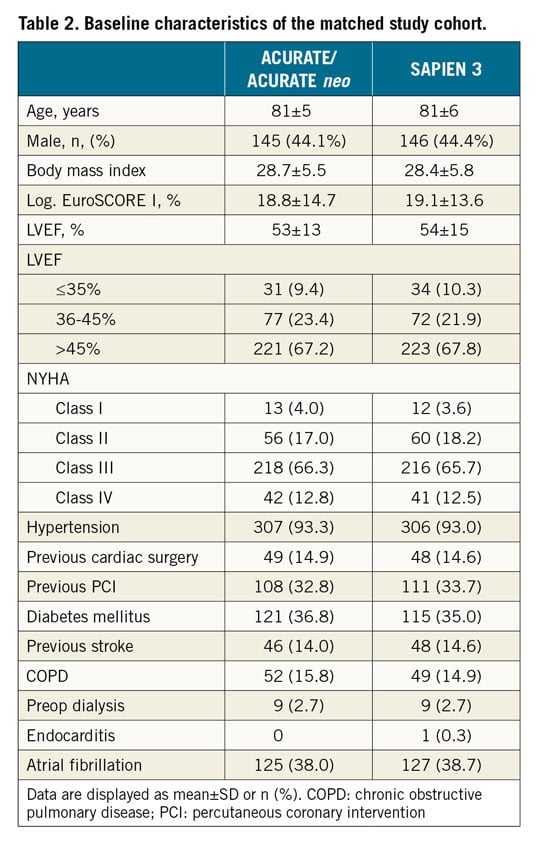

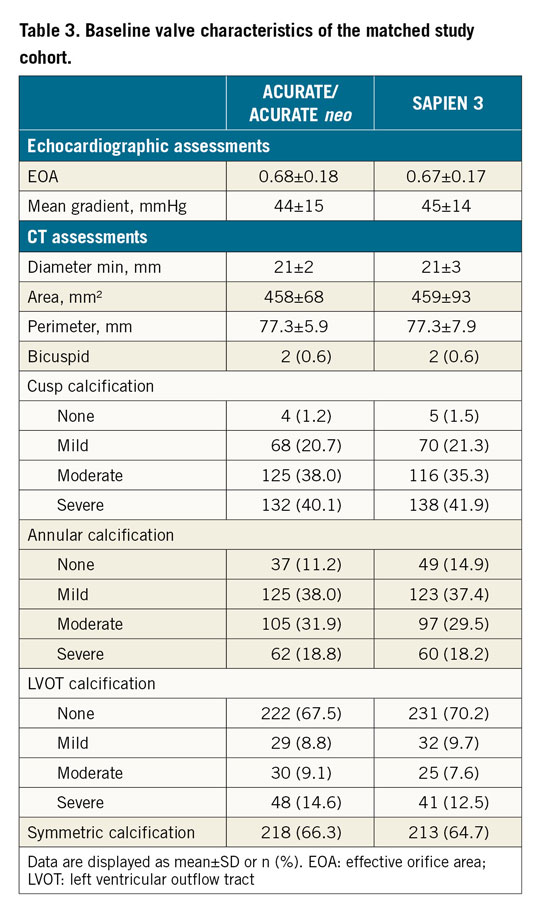

In the unmatched cohort, the ACURATE/ACURATE neo group had more females, smaller annuli, lower gradients, less cusp and annular calcification, more left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) calcification and more symmetric calcification compared to the SAPIEN 3 group (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2). In the matched cohort, baseline characteristics were similar between the groups. Mean patient age was 81 years and the logistic EuroSCORE I was 19%. More than three quarters of the patients had moderate to severe cusp calcification respective to none to mild LVOT calcification (Table 2, Table 3). The baseline and valve characteristics per centre are provided in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4.

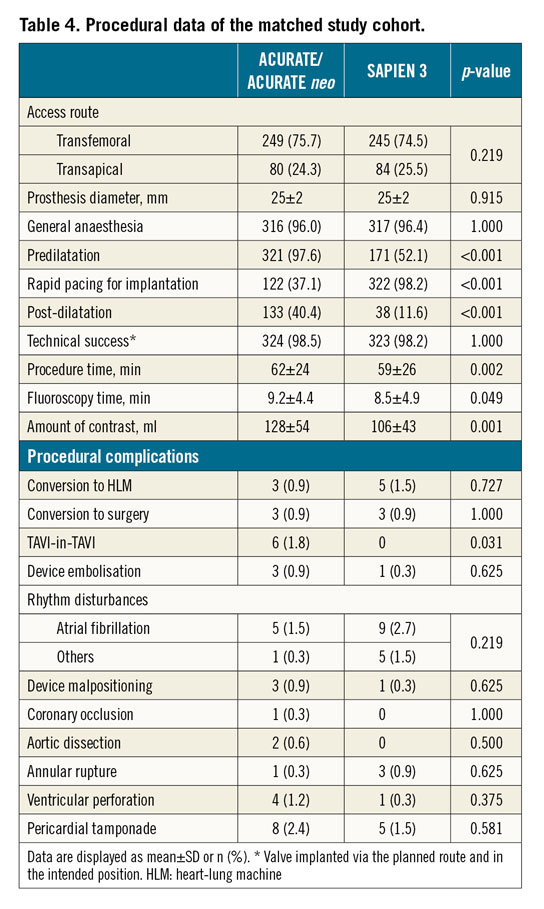

Nearly all patients (96%) received general anaesthesia. Patients treated with the ACURATE neo had significantly more predilatation performed (97.6% versus 52.1%, p<0.0001), less rapid pacing for implantation (37.1% versus 98.2%, p<0.001) and more post-dilatation (40.4% versus 11.6%, p<0.001). There was a significant difference in the rate of post-dilatation amongst the three centres (7.0%, 18.3% and 35.7%, p<0.001). There were no differences in technical success and procedural complications between the groups except for TAVI-in-TAVI, which was more frequent in the ACURATE group (n=6, 1.8% versus 0%, p=0.031) (Table 4, Supplementary Table 5).

All six TAVI-in-TAVI patients were treated via transfemoral access. Cusp calcification was mild in one patient, moderate in three, and severe in two; annulus calcification was absent in one patient, mild in four and severe in one. Calcification of the LVOT was absent in all cases. Rapid pacing for implantation was used in three cases and post-dilatation in two. Device malpositioning occurred in two, one of which resulted in a device embolisation. All TAVI-in-TAVI patients were alive at follow-up. Postoperative echocardiographic data are available for four patients; in all, aortic regurgitation was absent.

The average hospital stay was 18±12 days (range 2-94) for the ACURATE group and 17±10 days for the SAPIEN 3 group (range 4-71 days), p=0.831.

For 20 patients in centre A (8.9%), 23 patients in centre B (5.0%) and 27 patients in centre C (4.4%) no post-procedural gradients were documented. Postoperative echocardiography revealed a lower mean gradient in the ACURATE group (8.6±4.6 mmHg versus 10.9±4.2 mmHg, p<0.001) and a higher aortic regurgitation rate (more-than-mild aortic regurgitation in 12.0% versus 3.1%, p<0.001). Therefore, more-than-mild aortic regurgitation differed significantly (p<0.001) amongst the centres with 6.0% (3/50) in centre A, 34.1% (29/85) in centre B and 3.4% (6/181) in centre C (Supplementary Table 6).

The ACURATE group had a numerically higher early safety composite outcome (14.0% versus 9.1%, p=0.073) and significantly fewer pacemaker implants at 30 days (11.9% versus 18.5%, p=0.018) compared to the SAPIEN 3 group. Device success (82.4% versus 91.5%, p=0.001) and clinical efficacy endpoints (80.9% versus 91.2%, p<0.001) favoured the SAPIEN 3 group significantly. Stroke rate (2.4% versus 0.9%, p=0.13) and 30-day mortality (4.6% versus 2.1%, p=0.08) did not differ between the groups. Furthermore, there was a large variation in 30-day mortality, ranging from 2.2% to 8.8%, p=0.06, per centre in the ACURATE/ACURATE neo group (Table 5). Patients with more-than-mild aortic regurgitation had a similar 30-day mortality as compared to patients without (4.8% versus 3.1%, p=0.44). VARC-2 criteria per centre are shown in Supplementary Table 7.

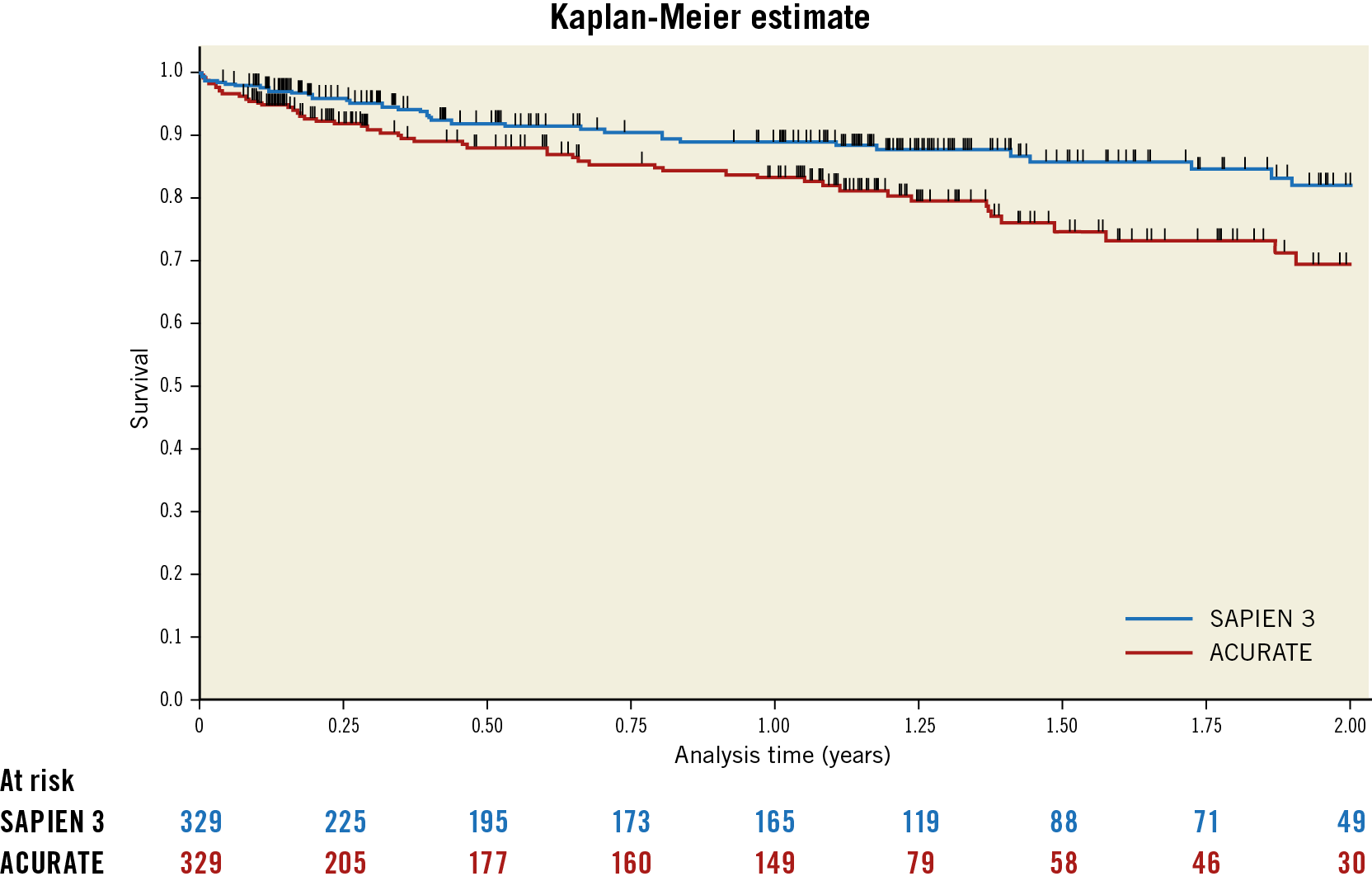

Mean follow-up was 319±291 days for the ACURATE group and 367±296 days for the SAPIEN 3 group; the median follow-up time was 364 versus 390 days, respectively. At one year (365 days), survival was 83.1% (95% CI: 77.6-87.4) and 88.8% (95% CI: 84.0-92.2), respectively (Figure 2). Considering the full follow-up time, Cox regression analysis revealed a hazard ratio of 1.89 (95% CI: 1.25-2.86) for the estimated linear mortality rate in the ACURATE group (p=0.02). There was no overlap of confidence intervals for the estimated linear mortality rate of the matched SAPIEN 3 group of 11.34% (95% CI: 8.18-15.71) and ACURATE group of 20.59% (95% CI: 15.88-26.69). There was a variation amongst the centres with a hazard ratio of 4.5 (95% CI: 1.24-16.34) for centre A, a hazard ratio of 3.0 (95% CI: 1.22-7.35) for centre B, and a hazard ratio of 1.15 (95% CI: 0.68-1.95) for centre C, where the acceptable severity of relevant aortic regurgitation appears to be less than in the other two centres. Survival curves per centre and per access route are provided in Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 2. If only patients without post-interventional aortic regurgitation are analysed (n=166), the hazard ratio of one-year mortality is 1.6. The survival rate was 88.8% (95% CI: 83.96-92.24) for the SAPIEN group and 83.14% (95% CI: 77.60-87.42) for the ACURATE group. For transfemoral access, the estimated linear mortality rate was 10.39% (95% CI: 7.08-15.26) in the SAPIEN group and 18.80% (95% CI: 13.30-26.59) in the ACURATE group. For transapical access, the rates were 14.84% (95% CI: 7.98-27.58) in the SAPIEN group and 23.43% (95% CI: 15.83-34.67) in the ACURATE group.

Figure 2. Survival of SAPIEN 3 versus ACURATE patients. Mean follow-up was 330 days.

Discussion

The unmatched population showed the typical distribution amongst ACURATE and SAPIEN 3 prostheses, with the ACURATE more frequently used in smaller annuli and hence in more females. This is attributed to the differences in valve size with the SAPIEN 3 offering larger prostheses; however, it may also be attributed to the supra-annular design of the ACURATE neo prosthesis making this valve particularly attractive in small annuli to avoid patient-prosthesis mismatch9. Furthermore, the tendency rather to use self-expanding prostheses in patients with less cusp and annular calcification or in patients with more LVOT calcification6 is reflected in the unmatched cohort.

Nearly all procedures were performed under general anaesthesia, according to the standard of care at the respective centres. We believe that there is no harm in conducting the procedure under general anaesthesia, even though a recent state-of-the-art paper states that – amongst other parameters – transfemoral implants under local anaesthesia may reduce invasiveness and costs2. Due to the lower radial strength of the ACURATE prostheses, more predilatation and post-dilatation were performed. In the SAVI-TF registry, post-dilatation after ACURATE neo implantation did not negatively affect clinical outcomes10.

The low pacemaker rate of the ACURATE prostheses, which is even lower than for the balloon-expandable SAPIEN 3 prosthesis, is not surprising and has already been reported in other propensity-matched comparisons7,9. However, what is striking in our series is the high rate of more-than-mild aortic regurgitation in the ACURATE group. It is intuitive that the lower radial strength of the ACURATE prosthesis may lead to a higher risk of regurgitation and multicentre propensity-matched comparisons have reported higher paravalvular leakage (PVL) rates for the ACURATE neo as compared to the SAPIEN 3 (4.8% versus 1.8%, p=0.01; in small annuli 4.5% versus 3.6%, p=ns)7,9. However, the more-than-mild PVL rates reported there and those observed in the 2,000 patients of the SAVI TA and TF registries (1.9% and 4.1%)11,12 were substantially lower than the 12% observed in our series; a recent state-of-the-art paper even reported a cumulative rate of only 1.7% for the ACURATE prosthesis2.

When interpreting the outcomes, the following points have to be considered. a) The ACURATE/ACURATE neo group includes the first patient implanted with this device and hence includes not only the operator learning curve but also the learning curve on how best to use the device10. In contrast, users of the SAPIEN 3 were able to implement the knowledge already gained with the precursor device, the SAPIEN XT. b) No core laboratory was used. Sizing issues did in fact lead to a wrong prosthesis selection. In another propensity-matched comparison, there was a significant difference in sizing between the ACURATE neo and the SAPIEN 3. Undersizing was observed in 5.9% of ACURATE neo versus 0% of SAPIEN 3 procedures, accurate sizing (within the size range) was observed in 85.9% versus 77.2%, and oversizing was observed in 8.2% versus 22.8%, p<0.0019. A similar trend was observed in our series. c) Assessing PVL in supra-annular prostheses is not easy; there might have been an overinterpretation of outcomes in the absence of an experienced core laboratory13,14.

There was a non-significant trend towards higher one-year mortality in the ACURATE/ACURATE neo group compared to the SAPIEN 3 group (16.8% versus 11.2%) and a higher estimated linear mortality rate. When excluding patients with post-interventional aortic regurgitation ≥1, an elevated hazard ratio for one-year mortality persists irrespective of access route for the ACURATE group, suggesting a harmful effect on survival exceeding the effect of valve type-related aortic regurgitation. In contrast, a propensity-matched comparison comparing the ACURATE neo with the SAPIEN 3 in patients with small annuli showed a non-significant trend towards lower mortality in the ACURATE neo group (8.3% versus 13.3%, p=0.233)9. Particularly in the transfemoral arm of this analysis, the one-year mortality for the ACURATE neo (16.9%) was higher than that observed in the propensity matching described above, higher than for the 1,000 patients of the SAVI-TF registry10 and higher than in a single-centre analysis6, all with single-digit one-year mortality. In contrast, the one-year mortality of the SAPIEN 3 (11.2%) was similar to other reports, e.g., 12.6% in the SOURCE 3 registry (including 87.1% transfemoral patients) and 14.4% in high-risk patients of the PARTNER trial (including 84% transfemoral patients)8,15. This negative trend was visible irrespective of access route, although smaller sample sizes prevented statistical significance.

These outcomes might in part be explained by the substantial differences amongst the centres. In relation to procedural techniques, centre C post-dilated more frequently than centres A and B due to a policy of “zero tolerance of more-than-mild paravalvular leak”. This “zero tolerance policy” is probably one of the reasons for the better survival in the ACURATE group in this centre as compared to the other centres.

Furthermore, in centre C, the regurgitation rate was in the expected range and no difference between the prostheses was observed (3.4% for ACURATE vs 1.1% for SAPIEN 3), whereas it was exorbitantly higher in centre B. Specifically, more-than-mild regurgitation rates in ACURATE patients were 6.0%, 34.1%, and 3.4% in centres A, B and C, respectively.

Centre C, with the lowest moderate or severe AR rate and best one-year survival (87.4% [95% CI: 79.6-92.3] compared to 75.4% [95% CI: 60.4-85.3] and 81.3% [95% CI: 70.1-88.6]) is also the centre with the largest series of implants. In contrast, the other two centres had either small patient numbers (centre A) or several different operators (centre B, which has operators from six different hospitals). Similarly, and in alignment with other studies, a recent publication of the compulsory German Quality Assurance Registry on Aortic Valve Replacement3 of more than 10,000 transfemoral implants conducted in 2014 in Germany showed that there is a continuous association of lower in-hospital mortality (and risk-adjusted mortality) with increasing TAVI volumes (p<0.001). Furthermore, procedure times and hospital stays were lower in more experienced centres3.

Limitations

Common in propensity-matched analysis is the possibility of unknown confounders. However, a strength of this study is the thorough propensity score matching, taking all known confounders into consideration. On the other hand, that also restricts the interpretation of results to this specific patient population. Echocardiographic and computed tomography core laboratory data would have been paramount for adequate comparison of aortic regurgitation amongst centres and to identify the root cause(s) of the unexpectedly high aortic regurgitation rate at one centre, e.g., sizing issues. Additionally, the ACURATE TA is outdated as the ACURATE neo TA system gained CE certification in June 201716. Data from the SCOPE I trial (NCT03011346), randomising patients to the ACURATE neo versus the SAPIEN 3 are expected to provide further clarity.

Conclusions

Treatment with the ACURATE or ACURATE neo resulted in fewer pacemaker implants and lower mean gradients compared to the SAPIEN 3 but comes with the price of more aortic regurgitation and possibly lower one-year survival. Large centre differences suggest that it is paramount to conduct post-dilatation for residual more-than-mild aortic regurgitation and to conduct TAVI in high-volume centres with experienced operators.

|

Impact on daily practice TAVI has become an established practice but should still be used only in experienced hands. The ACURATE neo appears to be particularly vulnerable to paravalvular leakage. Therefore, undersizing should be avoided. Furthermore, meticulous post-dilatation in case of residual paravalvular regurgitation appears to be mandatory to achieve survival rates comparable to usage of the SAPIEN 3 prosthesis. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Beatrix Doerr for her editorial assistance, reimbursed by Symetis SA, a Boston Scientific company.

Conflict of interest statement

K. Hamm reports non-financial support from Boston Scientific, from null, during the conduct of the study. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.