CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: The ideal treatment of spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is still controversial.

INVESTIGATION: A young 39-year-old woman without cardiovascular risk factors presented with acute chest pain, following a quarrel. The admission electrocardiogram showed mild ST-elevation in V2-V3 anterior leads. Echocardiography revealed left ventricular apical dyskinesis, mimicking Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

DIAGNOSIS: Coronary angiography showed SCAD extending from the mid to distal left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, confirmed by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS).

MANAGEMENT: After predilation, three BVS were implanted with partial overlapping. Diagnosis of Takotsubo was ruled out in the presence of SCAD.

KEYWORDS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold, coronary angioplasty, spontaneous coronary artery dissection, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

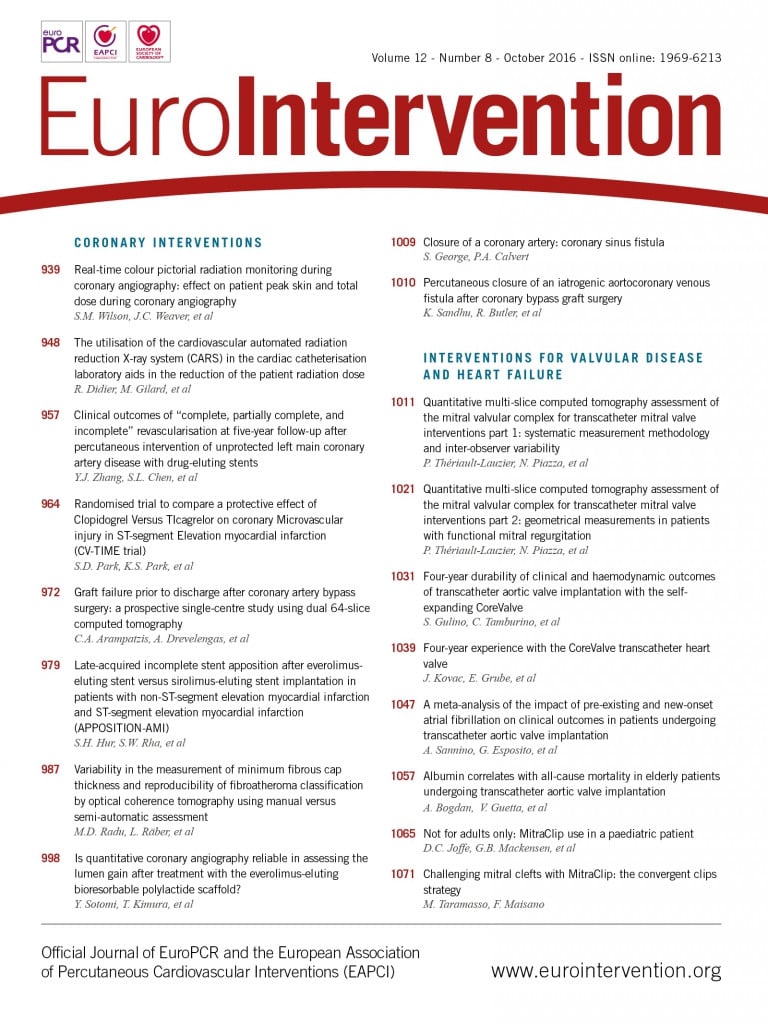

A young 39-year-old woman without cardiovascular risk factors presented with acute chest pain, radiating to her left arm, following a quarrel with her mother. The admission electrocardiogram showed mild ST-elevation in V2-V3 anterior leads (Figure 1) and raised troponin levels (3.7 ng/ml). Echocardiography revealed left ventricular apical and mid-wall dyskinesis, mimicking Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (LVEF 35%).

Figure 1. Electrocardiograms. A) Electrocardiogram at admission showing mild ST-elevation in V2-V4 anterior leads. B) Electrocardiogram after coronary angioplasty showing diffuse ST/T anomalies with ST-elevation, negative T-waves and QT prolongation.

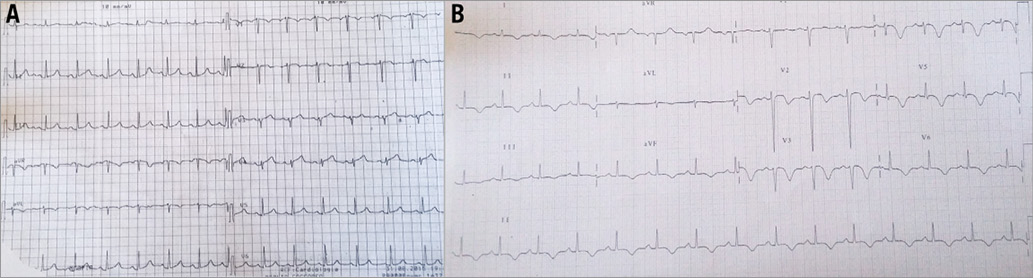

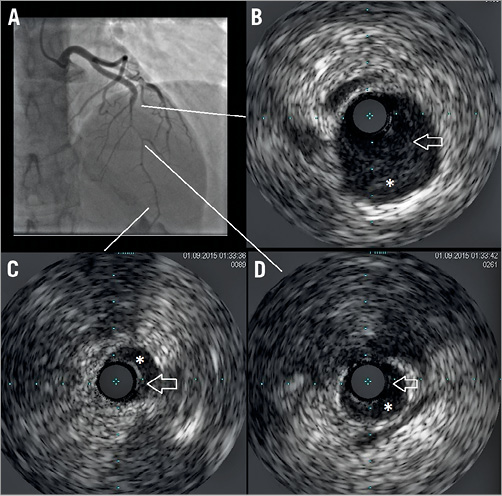

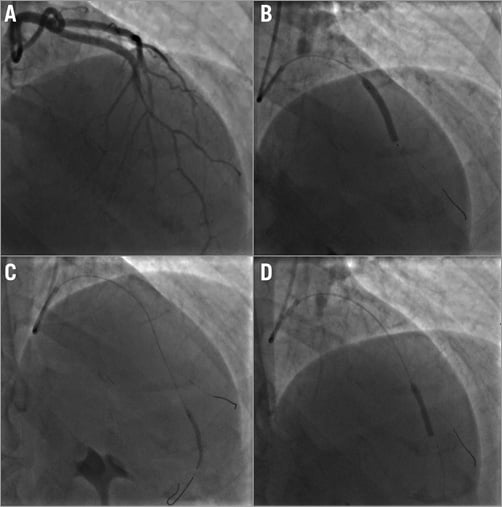

The woman was hence admitted to the cathlab where coronary angiography showed a mild intraluminal filling defect suggestive of SCAD, extending from the mid to distal left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery (Figure 2A, Moving image 1). SCAD diagnosis was confirmed by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) examination which showed the presence of SCAD throughout a large part of the LAD with partially organised intraparietal haematoma (Figure 2B-Figure 2D, Moving image 2). No evidence of lesions was found in the right coronary artery (Figure 3A). Apical ballooning was confirmed at left ventricular angiography (Figure 3B).

Figure 2. Coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. A) Coronary angiography showing filling defects in mid and distal left anterior descending coronary artery. Intravascular ultrasound imaging in proximal (B), distal (C), and mid (D) segments of coronary dissection (arrow: intima flap; asterisk: partially organised intracoronary haemorrhage).

Figure 3. Left ventricular and right coronary angiography. A) Left ventricular angiography showing mid and apical dyskinesis mimicking Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, ruled out after coronary angiography. B) Right coronary angiography in the absence of significant coronary disease.

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is reported in young women after acute distress1. Among patients undergoing coronary angiography, it was estimated that 0.2%-1.1% had SCAD2, while, among young women (age <50 years) with acute coronary syndrome, the prevalence of SCAD may be even higher, occurring in 8.7% of patients with acute coronary syndrome and 10.8% with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)3.

The ideal treatment for such a clinical entity is still controversial4. However, bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) devices have recently been introduced into clinical practice5. BVS are characterised by the great clinical advantage of a complete recovery of coronary dilative capacity after complete degradation of the polymer scaffold6.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

This young female presented with a spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) following an episode of emotional stress. Emotional stress has been considered a classic trigger for Takotsubo (TT) cardiomyopathy and, more recently, also for SCAD, especially among female patients7. The patient presented with an acute myocardial infarction and underwent urgent coronary angiography that provided the diagnosis. On angiography, the entire left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was visualised with, apparently, a good distal flow. However, an abrupt reduction in vessel calibre was observed in the mid LAD with a characteristic “broken line” appearance, highly suggestive of SCAD8,9. “Milking” of the LAD, clearly visualised, has also been described in this condition. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) readily confirmed the double lumen and disclosed the full extent of the disease. At this moment, the most important clinical decision is whether the SCAD should be treated right away with coronary stents or rather whether a conservative “watchful waiting” strategy should be selected8-10. Considering the angiographic appearance of the vessel, the mild ECG changes, the residual lumen on angiography and the IVUS appearance, we would have favoured an initial conservative strategy10. Aspirin and beta-blockers are empirically advocated in this scenario9. In our experience, a conservative initial medical strategy provides excellent clinical outcomes for most “stabilised” patients with SCAD10. Indeed, after the initial ischaemic insult, most of these patients become asymptomatic and eventually evolve with complete vessel healing at late follow-up. Moreover, recent data from the Mayo Clinic suggest that revascularisation (either percutaneous or surgical) in these patients is frequently associated with procedure-related complications (haematoma propagation) and poor long-term outcomes11.

The association of TT cardiomyopathy with SCAD has been reported in anecdotal cases with angiographically normal coronary vessels in which the diagnosis was eventually unveiled by intracoronary imaging10. In this young female, however, the LAD was diffusely diseased. Recovery of the left ventricular function should be demonstrated before this association is even considered.

Coronary intervention should be attempted if the patient has persistent chest pain, presents with an occluded vessel or experiences recurrent or refractory symptoms10. Considering the length of the disease a complex procedure may be anticipated10. Currently, we prefer optical coherence tomography (OCT) rather than IVUS in order to identify better the entry door and the intimal flap12,13. The unsurpassed axial resolution of OCT provides striking views of the underlying pathological substrate12. In our experience, OCT is frequently able to unravel intimal ruptures missed by IVUS12. IVUS, however, has a superior tissue penetration, allowing a complete delineation of the entire vessel wall even in patients with a large false lumen/intramural haematoma13.

The “entry tear” should be sealed by the stent that should also cover the most severely diseased segment10,12. However, residual coronary dissection or intramural haematoma should be left untreated providing the residual coronary lumen is large and coronary flow is not compromised. The fate of these untreated segments is largely favourable with complete vessel healing with restitutio ad integrum of the vessel wall12. Obviously, this conservative stenting strategy cannot be applied to patients with distal dissection causing severe lumen narrowing or when iatrogenic “progression” of the intramural haematoma generates significant lumen compromise11. Although it has been speculated that drug-eluting stents (DES) might prevent the natural healing of the vessel wall, this concern remains purely speculative. Therefore, we always offer DES when relatively long coronary segments are to be tackled9. Recently, some novel and provocative percutaneous strategies have been suggested for patients with SCAD9. First, vessel fenestrations with scoring balloons generate large connections between the true and the false lumen or decompress large intramural haematomas, eventually resulting in a wider true lumen14. However, experience with these techniques in the coronary territory is very limited14. The use of bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) in this setting is very appealing. Acutely, BVS would provide the required scaffold of the true lumen whereas at long-term follow-up these devices may facilitate complete vessel wall restoration15. However, BVS implantation may be challenging in the tortuous “curly”, small and diffusely diseased vessels that characterise this entity16. When possible, a conservative BVS strategy sealing only the most proximal segment of the vessel would appear most attractive. Preliminary results suggest favourable long-term outcomes of patients treated with BVS15.

Last but not least, CT angiography should be used to monitor the evolution of the affected vessel during follow-up9. Furthermore, the presence of associated “fibromuscular dysplasia” of non-coronary large arterial beds (iliac, renal, cerebral) –a highly prevalent associated condition– should be ruled out by a dedicated CT angiographic evaluation7,9.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERT’S OPINION

Ruggiero et al present the case of a 39-year-old woman with extensive spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) of her mid-distal left anterior descending (LAD) artery, with a type 2 angiographic appearance17, and confirmation of intramural haematoma on intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). Her event was provoked by emotional stress. She had ~1 mm ST-elevation in her anterolateral leads, and minor troponin elevation. In this particular case, the dissection length was extensive (>70 mm), and her LAD was a long vessel wrapping around the left ventricular apex, resulting in the large “apical ballooning” on angiography. There was no description of her clinical status upon presentation at the cardiac catheterisation laboratory, which is instrumental in guiding management.

The preferred management of SCAD is conservative, unless the patient has high-risk features of ongoing ischaemia, haemodynamic instability, ventricular arrhythmia, or left main dissection. The rationale for this approach was prompted by the poor acute success rate of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for SCAD lesions (~50-70%)7,11,18, coupled with the observation that the vast majority of SCAD arteries heal spontaneously7. The challenges with PCI for SCAD include the heightened risks of iatrogenic catheter-induced dissection in already weakened arteries, entry of coronary wire into the false lumen, extension of intramural haematoma with angioplasty/stenting, extensive lengths of stents required, and risks of acute/subacute stent thrombosis and longer-term in-stent restenosis19. For this patient, unless there was ongoing chest pain, our preference would be conservative medical therapy, with observation in-hospital for three to five days. The in-hospital medication regimen should include aspirin, clopidogrel, beta-blocker, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Long-term medications should include aspirin and a beta-blocker19. With this conservative management approach, we have observed low recurrent in-hospital myocardial infarction of <5%, and spontaneous angiographic healing in all patients on repeat angiography performed after four weeks7.

On the other hand, if this patient exhibited evidence of ongoing ischaemia with ongoing chest pain or haemodynamic instability, then PCI should be pursued. With PCI, adjunctive IVUS or optical coherence tomography (OCT) should be considered to confirm that the coronary wire is in the true lumen, the extent of dissection, and to maximise stent strut apposition. Given that multiple and long stents are typically required, and that resorption of intramural haematoma may cause subsequent stent malapposition and risk of thrombosis20, bioabsorbable stents may be preferred over metallic stents19. In this case, if PCI was required, I would favour OCT to confirm wire location and to assess the extent (length) of intramural haematoma, and then place multiple bioabsorbable stents to cover the entire length of the dissection, with 5-10 mm edge coverage of normal segments.

Conflict of interest statement

J. Saw received research grants for SCAD research (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, University of British Columbia Division of Cardiology, AstraZeneca, Abbott Vascular, St. Jude Medical, and Servier), and speaker honoraria for SCAD (AstraZeneca, St. Jude Medical, and Sunovion).

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE CASE

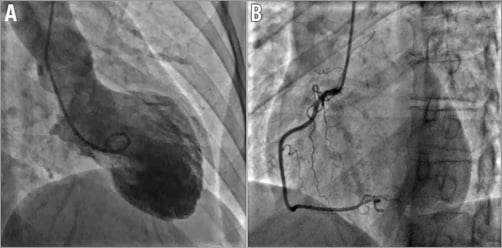

After selective LAD cannulation and double guidewire placement into the LAD and distal diagonal branch, a strategy of coronary stenting was decided upon. After predilation, three BVS (Absorb; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were implanted with partial overlapping (distally to cranially 2.5×28 mm, 3×28 mm, 3.5×28 mm). Final angiography after post-dilation showed optimal LAD size and perfusion (Figure 4A-Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Coronary angioplasty. A) Left coronary angiography before coronary angioplasty showing mid and distal filling defects caused by spontaneous coronary dissection. B), C), & D) Coronary balloon inflation with deployment of bioresorbable vascular scaffold in mid and distal left anterior descending coronary artery.

Electrocardiograms after coronary angioplasty showed diffuse ST/T anomalies (ST-elevation and negative T-waves) with QT prolongation, which were present throughout the whole hospitalisation (Figure 1).

The patient was discharged after one week with evidence of partial recovery of left ventricular function (ejection fraction 45%), on treatment with nebivolol, furosemide, aspirin, atorvastatin and ticagrelor.

A diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was ruled out in the presence of SCAD. Peak troponin level was 25 ng/ml.

To the best of our knowledge, we have shown for the first time in this female patient the complete “polymer” jacketing of the LAD in the case of SCAD extending from mid to distal LAD. Cases of full “polymer” jacketing have, however, been reported previously but on the right coronary artery21. The use of intracoronary imaging is extremely helpful in identifying the exact limits and the entire extent of SCAD22. Also, cases of SCAD mimicking Takotsubo cardiomyopathy have already been reported23.

Despite the use of BVS having been extensively reported in controlled studies on simple coronary lesions24, BVS implantation for the treatment even of complex coronary lesions has been increasingly implemented in common clinical practice25.

Nowadays, BVS are also used for primary coronary angioplasty in ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction26, diabetics27, and complex coronary lesions28. Data from all-comers registries describe the use of BVS as feasible and safe29.

Given the expected restoration of coronary vasodilator capacity after a bioresorption period30, the use of BVS could be particularly indicated in young patients without evidence of diffuse coronary atherosclerosis31.

In conclusion, the use of BVS could be feasible for the treatment of extended SCAD in young women without significant cardiovascular risk factors and significant coronary disease.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

Moving image 1. Coronary angiography showing spontaneous coronary artery dissection on LAD.

Moving image 2. IVUS imaging showing presence of SCAD throughout a large part of the LAD with partially organised intraparietal haematoma.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Coronary angiography showing spontaneous coronary artery dissection on LAD.

IVUS imaging showing presence of SCAD throughout a large part of the LAD with partially organised intraparietal haematoma.