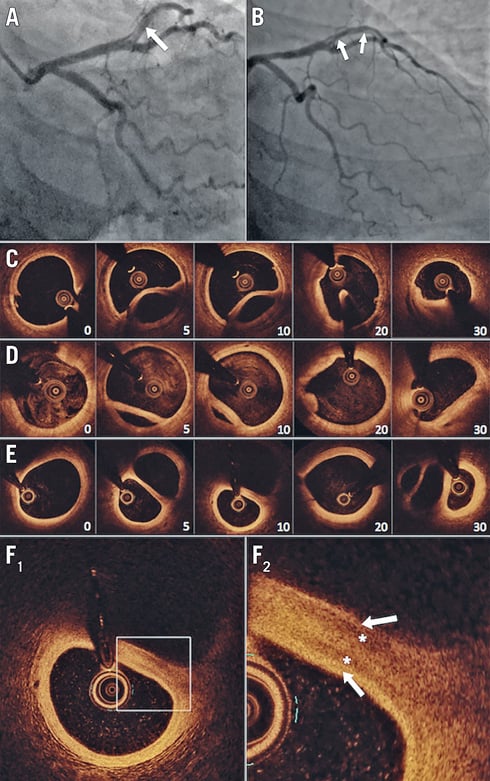

Figure 1. Spontaneous LAD dissection course over time. A) Initial coronary angiography following manual thrombectomy and 1st diagonal branch PCI depicted mid LAD spontaneous dissection (arrow). B) Five-year follow-up coronary angiography revealed a double lumen aspect on mid LAD (arrows). C) – E) Serial head-to-head LAD OCT analyses at 48 hours (C), 40 days (D) and five years (E) showed progressive healing of lumens leading to presence of two circulating arterial conduits (the numbers indicate the distance [mm] between LAD ostium and OCT cross-section). F) Five-year proximal LAD OCT analysis. The healed thickened flap revealed a multi-layered aspect that was compatible with presence of media (asterisks) and intima (arrows) within each conduit wall.

A 51-year-old woman was referred to our institution with an anterolateral ST-elevation myocardial infarction related to a subocclusive spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) extending to left anterior descending (LAD) and 1st diagonal (Dg1) arteries. Manual thrombectomy was successively performed in both branches and a large abundant red thrombus was removed from the vessel, leading to restoration of normal flow in the distal LAD but not in the Dg1. As the patient still reported chest pain and ST elevation did not normalise, the diagonal branch was treated by 2.5x38 mm everolimus-eluting stent implantation, which led to complete symptom resolution (Figure 1A, Moving image 1). No additional intervention was performed on the LAD dissection that was treated conservatively.

Subsequent optical coherence tomography (OCT) analysis was performed at 48 hours to examine the LAD further. It confirmed SCAD, extending from the ostium to the distal part of the artery (Figure 1B), with multiple intimal tears dissecting the media, a false lumen of varying size with a collapsed aspect in the distal LAD, and no signs of residual thrombus or atherosclerotic plaque (Figure 1C, Moving image 2). Owing to the lesion’s characteristics and the clinical stability, conservative management was decided upon. The patient was discharged on day 5.

A subsequent scheduled follow-up was performed 40 days later. There was no significant change in angiography but OCT showed that the dissection was healing with a thickened dissection flap (Figure 1D, Moving image 3). With the continued clinical stability, no additional procedure was performed.

The clinical course up to five years was uneventful. Dual antiplatelet therapy was provided for 12 months following STEMI and then switched to aspirin alone. Several non-invasive tests ruled out any probability of recurrent ischaemia and confirmed normal left ventricle function. In consultation with the patient, we decided to do a follow-up coronary angiography (Figure 1B, Moving image 4) plus OCT analysis (Figure 1E, Moving image 5). This revealed complete healing of the dissection and identified two arterial conduits in the proximal and mid LAD, corresponding to the initial false and true lumens. Re-arterialisation (as assessed by the presence of intimal, medial and adventitial layers) (Figure 1F) was observed in both conduits. Subsequent explorations by methylergonovine and nitroglycerine intracoronary injections revealed no abnormality.

Although potential exists for early extension (that affects an initially dissected arterial segment) or late recurrence (which involves a not previously dissected segment)1, SCAD also frequently resolves ad integrum with a favourable OCT aspect and without clinical sequelae at follow-up2,3. In our case, the initial thrombectomy allowed extraction of a large red thrombus that, in the light of the subsequent evolution and OCT images, was probably the false lumen haematoma that occluded the LAD. We believe that thrombectomy in this very particular case was beneficial: it removed the false lumen haematoma, hence decreasing the tension and allowing circulation in both LAD lumens. Our observation illustrates an unusual spontaneous healing process of SCAD, leading to a double lumen vessel. Our case suggests that a conservative approach may be considered even in cases of large, angiographically visible SCADs (given a clinical stability and adequate coronary flow) due to the potential for long-term vessel healing.

Conflict of interest statement

N. Amabile reports consulting fees from Abbott Vascular, Biosensors and Boston Scientific. G. Souteyrand reports consulting fees from Abbott Vascular and Terumo. P. Motreff reports consulting fees from Abbott Vascular and Terumo. C. Caussin reports consulting fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific and Medtronic.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Moving image 1. Initial coronary angiography following manual thrombectomy and 1st diagonal branch PCI during STEMI.

Moving image 2. LAD OCT analysis 1 (48 hours after STEMI).

Moving image 3. LAD OCT analysis 2 (40 days after STEMI).

Moving image 4. 5-year follow-up coronary angiography.

Moving image 5. LAD OCT analysis 3 (5 years after STEMI).