Abstract

Aims: Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an underdiagnosed entity of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Its prevalence remains unclear due to a challenging diagnosis, particularly in instances of intramural haematoma without intimal rupture. In the present study, we aimed to: 1) estimate the prevalence of SCAD among acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients managed in a French coronary care centre, 2) demonstrate the value of specific angiographic signs for diagnosing SCAD, and 3) confirm the incremental value of intracoronary imaging in ambiguous cases.

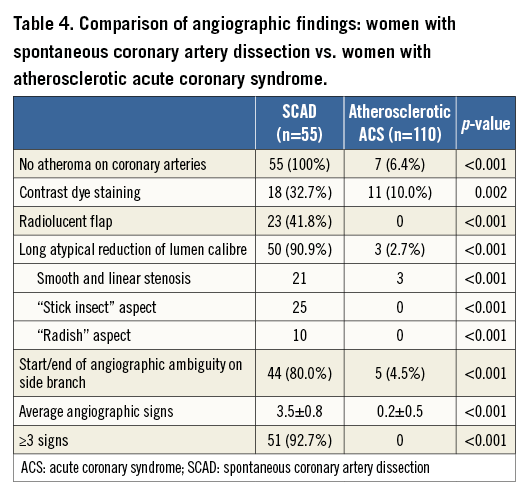

Methods and results: From 1999 to 2014, 55 cases of SCAD (all women, mean age 50.1 years) were diagnosed. Ignoring age, 51 (92.7%) had ≤2 cardiovascular risk factors. Thirty-six were diagnosed prospectively during the latter period (2012-2014). Among these, SCAD accounted for 35.7% of ACS (20/56) in women <60 years with ≤1 cardiovascular risk factor. Upon close investigation, five angiographic features commonly observed with SCAD were identified: 1) absence of atheroma on other coronary arteries, 2) radiolucent flap(s), 3) contrast dye staining of the arterial wall, 4) starting and/or ending of the angiographic ambiguity on a side branch, 5) long narrowing of lumen calibre: smooth and linear, or stenosis of varying severity mimicking a “stick insect” or “radish” aspect. Three of the above five signs were present in 51 (92.7%) cases. Optical computed tomography (OCT) was performed in 19 cases with no complication. All explored arteries had evidence of intramural haematoma and/or intimomedial membrane separation. An intimal rupture was observed in 10 (52.6%) patients. The diseased segment initiated or ended on a side branch in 14 (73.7%) patients.

Conclusions: SCAD accounts for approximately one third of ACS in young women with ≤1 CRF. The combination of specific angiographic signs and OCT imaging facilitates the diagnosis of ambiguous cases without intimal rupture.

Introduction

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is a severe and underdiagnosed clinical entity that frequently presents as an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), affecting young women predominantly. Its overall prevalence remains unclear, varying from 0.1% to 1.1% in most angiographic series1-3. Several reasons indicate that this is an underdiagnosed condition. First, presentation as sudden death, with the diagnosis established post mortem on autopsy findings in early reports4, may at least partially explain the underrecognition of this condition. Second, the widespread belief among physicians that young women are at low risk of acute coronary events is responsible for an underuse of coronary angiography in young females with chest pain. Third, the well-known limitations of coronary angiography in visualising the vessel wall contribute to the misdiagnosis of SCAD, especially in cases of intramural haematoma without intimal rupture. The pathognomonic appearance of dissection with intimal rupture as a radiolucent flap is easily recognisable on angiography5. In contrast, the assessment of luminal narrowing in case of intramural haematoma is more subtle, and remains a challenge for clinicians confronted with a suspicion of SCAD. Large series of patients have recently been published providing additional insights on the prevalence and diagnosis of this poorly understood disease6-8. In the light of these recent data, the prevalence of SCAD is much higher than previously described. Indeed, Saw et al showed that SCAD accounts for almost 25% of all ACS with MI in women under 50 years of age9. A recently proposed classification provides additional help for the diagnosis and distinguishes two angiographic aspects of intramural haematoma: i) long and diffuse stenosis varying in severity from mild to complete occlusion and involving distal arterial segments (Type 2), or ii) more focal stenosis mimicking atherosclerosis (Type 3)5. In case of ambiguities, the value of optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been demonstrated to assess arterial wall integrity and to diagnose both dissection and intramural haematoma10,11. Despite these recent data, there is still a need to assess the prevalence of SCAD and to increment specific angiographic semiotics to facilitate SCAD recognition.

In the present study, we aimed to: 1) estimate the prevalence of SCAD among acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients managed in a French coronary care centre, 2) demonstrate the value of specific angiographic signs for diagnosing SCAD, and 3) confirm the incremental value of intracoronary imaging in ambiguous cases.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

Patients with confirmed SCAD referred to our institution were retrospectively identified from October 1999 to December 2011 (n=19). From 2012 to 2014, patients with a clinical and angiographic suspicion of SCAD (n=36) were prospectively enrolled and underwent OCT when it was presumed to contribute to diagnosis and/or management. SCAD was defined as a clinical ACS with myocardial infarction confirmed by typical diagnostic features (intimal dissection and/or intramural haematoma) identified by angiography and/or OCT imaging10. Patients with iatrogenic coronary artery dissection were not included. In order to estimate the prevalence of SCAD among ACS patients, specific focus was given to the prospective period of our study (2012-2014). The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

ANGIOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS

When this study first began to record SCAD prospectively in 2012, the classification proposed by Saw had not yet been published5. Intimal tear was defined on angiograms as the presence of a radiolucent plane often associated with contrast dye staining. Intramural haematoma was identified by an abrupt vessel tapering in patients with a high suspicion index for SCAD. Coronary angiograms were reviewed by two interventional cardiologists experienced in SCAD. The diagnosis was then confirmed by the presence of intramural haematoma on OCT imaging10 or by the observation of spontaneous vessel healing on angiographic control performed at follow-up at the discretion of the operator. Angiographic characteristics of SCAD patients, including the number of diseased vessels, their location and lesion characteristics, were recorded12.

OCT IMAGING

OCT imaging was performed when technically feasible (adequate vessel calibre, absence of artery tortuosity) using the second-generation frequency domain system, C7-XR™/ILUMIEN™ (LightLab Imaging [now St. Jude Medical], Westford, MA, USA), or LUNAWAVE® (Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Prior to imaging, 70 IU/kg of unfractionated heparin and an additional bolus of intracoronary nitroglycerine were administered. Care was taken to navigate the guidewire gently across the diseased coronary segment. The diagnosis of SCAD on OCT imaging required the presence of intramural haematoma and/or double lumen10. The length of the diseased segment was measured to assess the longitudinal extent of dissection and/or haematoma. True and false lumen areas were analysed to determine the smaller true/false lumen ratio. The visualisation of intimal rupture and the initiation and/or ending of the dissection on a side branch were also assessed.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS AND CARDIOVASCULAR RISK FACTORS

Clinical history, hospital presentation and baseline data were obtained by a combination of patient interviews and hospital records. Cardiovascular risk factors (CRF) including current tobacco use, family history of CAD, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and obesity (BMI ≥30) were recorded.

COMPARISON OF SCAD PATIENTS TO GROUPS OF ATHEROSCLEROTIC ACS

In order to assess the “cardiovascular risk profile” of SCAD patients, the CRF of SCAD patients aged <60 years were compared with a control group comprising a sample of consecutive women aged <60 years admitted to our institution for “atherosclerotic ACS” during the last four years. The terminology “atherosclerotic ACS” encompassed all identified ACS of atherosclerotic origin on the angiogram. To estimate the value of our angiographic findings in diagnosing SCAD, the observed findings in SCAD patients were compared with a control group comprising a randomly drawn sample of “all comers” women diagnosed with atherosclerotic ACS in our institution during the last four years (two controls for one SCAD, as typically recommended).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 13 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The tests were two-sided, with a type I error set at α=0.05. Subject characteristics are presented as mean (±standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) according to statistical distribution (assumption of normality assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test) for continuous data and as number of patients and associated percentages for categorical parameters. Comparisons between independent groups (SCAD and atherosclerotic ACS) were performed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test when t-test conditions were not met (normality, assumption of homoscedasticity verified using the Fisher-Snedecor test).

Results

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND CARDIOVASCULAR RISK PROFILE

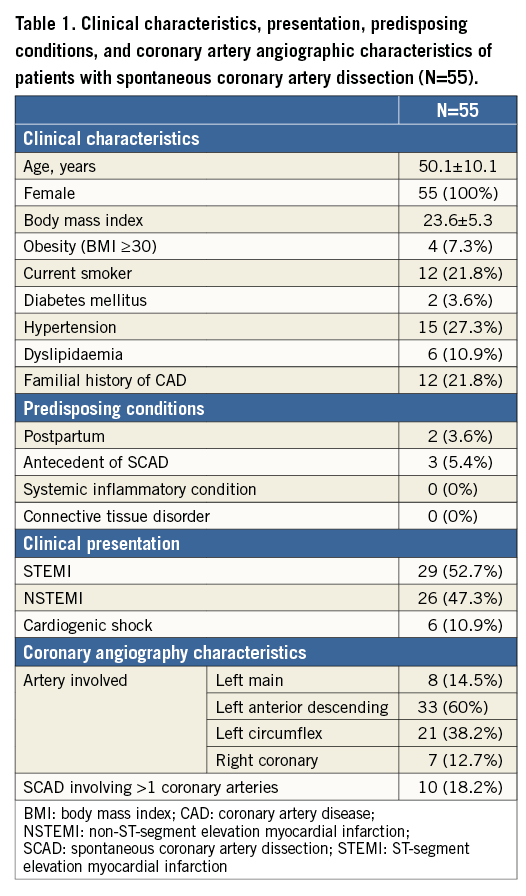

The clinical characteristics, presentation and angiographic characteristics are listed in Table 1.

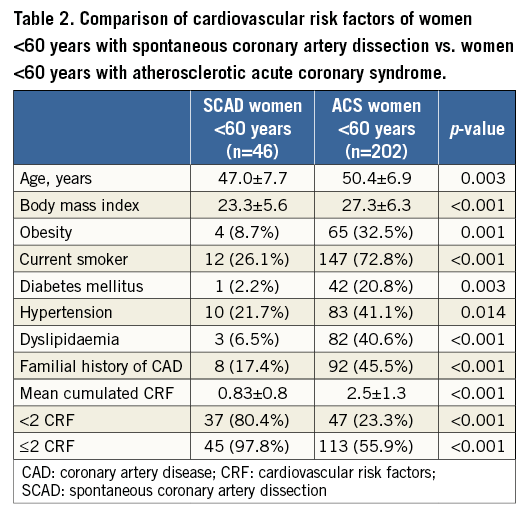

All fifty-five (100%) included patients were women. Mean age was 50.1±10.1 years; 46 (83.6%) were aged <60 years. Clinical presentation was ST-elevation (STEMI) in 29 cases (52.7%) and non-STEMI in 26 cases (47.3%). Six (10.9%) patients initially presented with concomitant cardiogenic shock. Only two (3.6%) occurred in the postpartum period. Three (5.5%) patients had a history of previous SCAD with a first episode occurring, respectively, 103, 87 and 23 months before the second event. When excluding age from the analysis, 51 (92.7%) had ≤2 CRF and 42 (75%) had ≤1 CRF. Differences in CRF between SCAD women aged <60 years (n=46) and the sample of consecutive women <60 years admitted to our institution for atherosclerotic ACS (n=202) are listed in Table 2. Initial management consisted of conservative therapy in 40 (72.7%) cases, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in 14 (25.5%) cases and emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery in one patient (1.8%).

PREVALENCE OF SCAD AMONG THE ACS POPULATION

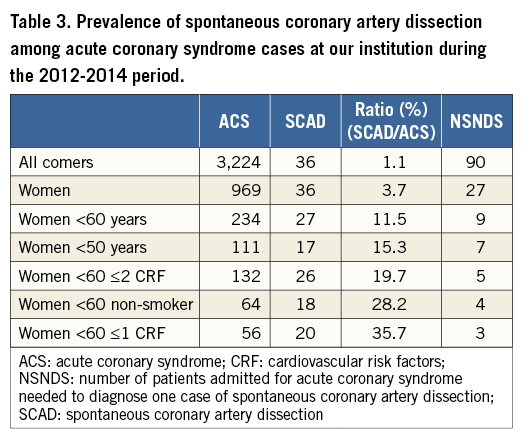

From 1999 to 2014, 55 SCAD cases were documented, 36 (65.4%) of which were diagnosed during the last three years. The prevalence of SCAD among ACS patients rose dramatically in instances of women with low CRF, such that the younger the patient and the lower the CRF, the greater the probability of having SCAD (Table 3). During the 2012-2014 period, the overall prevalence of SCAD was 1.1% (36 SCAD/3,224 ACS), rising to 11.5% in women aged <60 years (27 SCAD/234 ACS), and further reaching 35.7% in women <60 years with ≤1 CRF (Table 3).

ANGIOGRAPHIC SIGNS OF SCAD

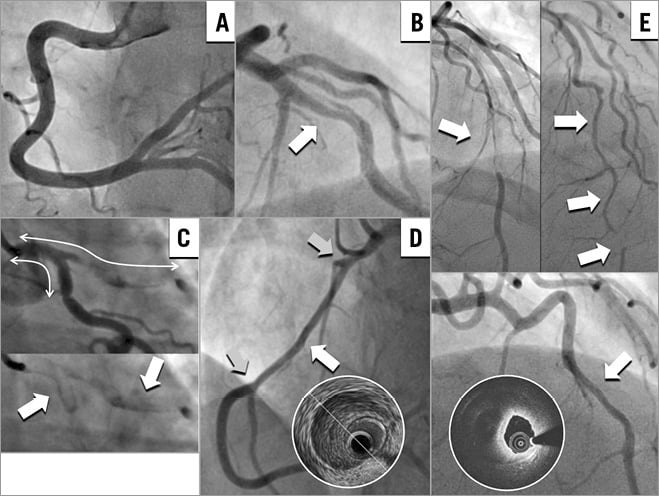

Multivessel dissection (contiguous and non-contiguous) was observed in 10 patients (18.2%). Upon review of angiograms, five angiographic features of SCAD were identified (Figure 1): 1) absence of atheroma on other coronary arteries, 2) radiolucent flap(s) generating at least two lumens, 3) contrast dye staining of the arterial wall, 4) starting and/or ending of the angiographic ambiguity on a side branch, 5) long narrowing of lumen diameter: smooth and linear, or stenoses of varying severity (from mild stenosis to occlusion, often distal) mimicking a “stick insect” or “radish” aspect.

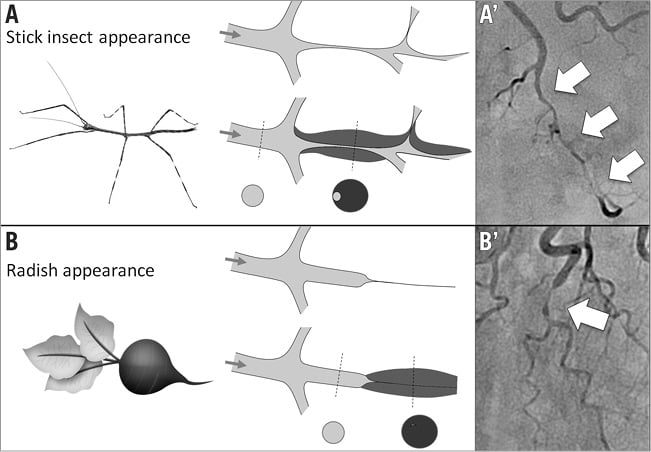

Multiple radiolucent flaps (observed in 23 cases [41.8%]) and extraluminal contrast dye staining (in 18 cases) were classically described as pathognomonic of SCAD with an intimal tear and revealed the presence of contrast in the false lumen. We identified a long and linear smooth-edge narrowing of the coronary lumen located on the proximal and middle segments in 21 patients. The “stick insect” aspect (observed in 25 cases) (Figure 2A) was due to an extrinsic compression of the lumen by the intramural haematoma whose longitudinal extension was often interrupted by a side branch. This appeared as a long stenosis, preferentially distributed to the middle and distal segments, with a biconcave aspect of the lumen which was more pronounced away from the side branches and of varying severity which at times resulted in complete occlusion (radish appearance illustrated in Figure 2B). Upon careful review of all angiograms, at least three of the five signs were present in 51 (92.7%) cases. Differences in angiographic appearance between SCAD patients (n=55) and a control group of sampled women admitted to our institution for a first atherosclerotic ACS (n=110) are listed in Table 4. Spontaneous healing, either partial or complete, was systematically observed at late angiographic control (performed in 43 [78.2%] cases, including 36 with conservative management, with a median delay of 60±39 days).

Figure 1. Angiographic features specific to spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). A) Absence of atheroma on other arteries. B) Radiolucent flap. C) Contrast dye staining in the false lumen. D) Starting and/or ending of the angiographic ambiguity on a side branch. E) Long narrowing of lumen calibre: smooth and linear (confirmed on OCT with the presence of intramural haematoma), or stenosis of varying severity (from mild stenosis to occlusion, often distal) mimicking a “stick insect” or “radish” aspect.

Figure 2. Angiographic appearances of luminal compression alone due to spontaneous coronary artery dissection with intramural haematoma. A) & A’) “Stick insect” appearance (long stenosis of varying severity with a biconcave aspect of the lumen, more pronounced away from side branches). B) & B’) “Radish” appearance when compression results in complete occlusion of the vessel.

INTRACORONARY IMAGING

Intracoronary imaging was performed in 22 cases (three intravascular ultrasound [IVUS]/19 optical coherence tomography [OCT]). From 2011 onwards, OCT was chosen exclusively and performed in case of suspicion of SCAD with intramural haematoma when technically feasible and judged to contribute to patient management. No complications (dissection or haematoma extension) related to intracoronary imaging catheter progression were encountered. All of the dissected arteries had evidence of intramural haematoma and/or intimomedial membrane separation with a double lumen10. An intimal rupture was observed in 10 (52.6%) patients. The length of the diseased segment was 34.4±18.8 mm, confirming the angiographic aspect of long stenosis. The intramural haematoma either initiated or ended on a side branch in 14 (73.7%) patients. The measurement of true lumen minimal area and false lumen largest area allowed the determination of a smaller true/false lumen ratio=0.49.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this single-centre cohort of SCAD is the largest described to date in Europe. The prevalence of SCAD in young women presenting with ACS in this series suggests that SCAD is currently underdiagnosed. Original comparisons with women admitted to our institution for atherosclerotic ACS demonstrate that SCAD could be easily suspected in the absence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and confirmed with the combination of specific angiographic signs and OCT imaging in cases of ambiguity.

HIGH PREVALENCE IN YOUNG WOMEN WITHOUT ATHEROSCLEROTIC RISK FACTORS

SCAD has typically been reported to be a rare cause of ACS, accounting for 0.1-4%13. Vanzetto et al first described a substantial proportion of SCAD in women under 50 years of age admitted for ACS. In their cohort, SCAD represented 8.6% of ACS in women under 50 years and 10.8% in cases of STEMI2. Recently, Saw et al showed that SCAD accounted for almost one quarter of all ACS with MI in women under 50 years9. Our current experience with ACS further demonstrates that the younger the patient and the lower the CRF, the greater the probability of having SCAD. This culminated in women <60 years with ≤1 CRF, in whom SCAD represented approximately one third of all ACS. Therefore, clinicians should henceforth have a very high level of suspicion for SCAD in young women without CRF presenting with ACS.

Compared to women with atherosclerotic ACS, SCAD patients had significantly fewer CRF, underscoring the absence of association with atherosclerosis. Nevertheless, the underlying cause remains largely uncertain. Several associated conditions have been described in case reports (connective tissue disorders, systemic inflammatory conditions, pharmacologic agents, etc.). Such predisposing factors were not found in the present cohort. Historical reports have suggested that pregnancy caused a substantial proportion of SCAD7; however, only two cases in the present series occurred during the postpartum period. This confirms the recent series estimation that postpartum SCAD accounts for <5% of cases overall7. Interestingly, three women had a personal history of a SCAD episode. This illustrates the previously described risk of recurrent SCAD occurring in 13-16% of cases in recent major cohorts6,7. Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) has been identified as an associated condition6,7,14-16. In the present cohort, only two cases of FMD on renal arteries were observed on CT scan imaging, although systematic FMD screening was not performed.

TYPICAL ANGIOGRAPHIC SIGNS OF SCAD

Limitations of coronary angiography in visualising the vessel wall are well known. The classic “dissection” form of SCAD is rarely missed by the physician, whereas the “haematoma” form (without intimal tear) constitutes a more challenging diagnosis.

The coronary angiographic signs identified herein are very similar to those described by Saw5. The combination of radiolucent flap and contrast dye staining is pathognomonic of the “dissection” form of SCAD with intimal tear classified by Saw as Type 1 SCAD. Over the first 19 cases from 1999 to 2011, 13 (68.4%) patients presented with the pathognomonic classic appearance of radiolucent flap often associated with contrast dye staining. By contrast, during the last three-year period, only 10 (27.8%) cases from the 36 diagnosed presented with such signs. This illustrates that luminal compression alone is the more common form of the disease10, and explains why SCAD is currently overlooked on angiograms. In case of the “haematoma” form of SCAD, which results in luminal compression alone, the assessment of arterial calibre narrowing is subtle. Similarly to Saw5, we identified two distinct expressions of arterial compression: 1) smooth and linear stenosis; 2) a more diffuse stenosis including variations in diameter which we describe in an imaged manner as “stick insect” or “radish” appearances that typify Type 2 SCAD (diffuse stenosis of varying aspect with an abrupt change in arterial diameter). In addition, we now introduce an important angiographic feature, which to our knowledge has not been described previously, namely the role of side branches in the initiation or the ending of the diseased segment. In our experience, haematoma often appears contained in an arterial segment between side branches. Our OCT findings confirm that SCAD frequently initiates or ends on a bifurcation. Our pathophysiological hypothesis to explain this angiographic aspect is that the “side branches” constitute anchoring points and can thus limit the extension of the subadventitial haematoma. The final important angiographic sign taken into account in our assessment is the otherwise constant absence of atheroma on other coronary arteries, illustrating that SCAD has no connection with atheroma. Altogether, the present analysis highlights the high value of the combination of these angiographic features in distinguishing SCAD from atherosclerotic stenosis in women with ACS.

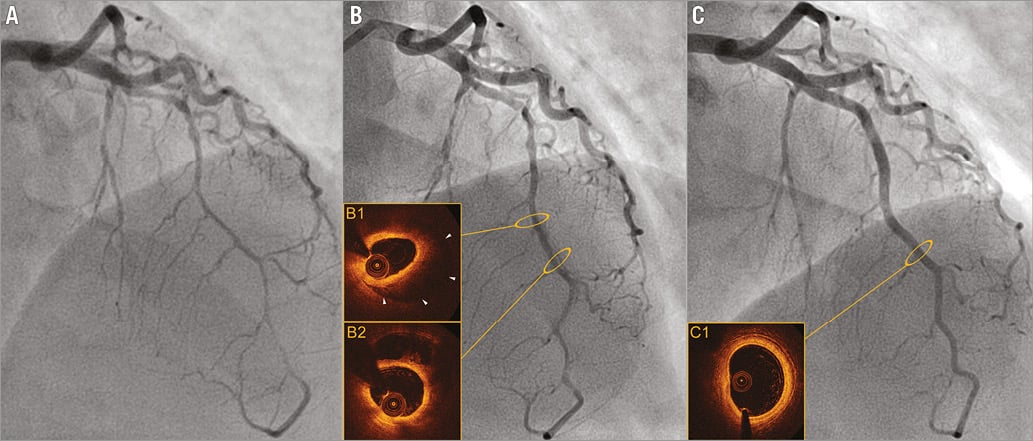

DIAGNOSIS OF SCAD: KEY ROLES OF INTRACORONARY IMAGING AND REPEATED ANGIOGRAMS

Our experience confirms the secure use of OCT as an adjunctive tool in the event of diagnostic ambiguity10,11,17. No complications were encountered with intracoronary imaging in this setting. OCT was useful to confirm diagnosis, particularly in instances of SCAD with intramural haematoma, and furthermore provided significant assistance in guiding PCI in five cases18,19. Intracoronary imaging contributed largely to enhancing our knowledge of the pathophysiology of SCAD. As a result, a continuum between the “haematoma” and “dissection” forms was observed which, in our opinion, indubitably share the same pathological mechanisms. Conversely to iatrogenic dissections in which the intimal rupture is clearly the trigger for the dissection, our observations in SCAD thus support the pathophysiological hypothesis of an initial intramural haematoma as a trigger of coronary artery dissection. We hypothesise that the haematoma initiates within the arterial wall and propagates in an anterograde or retrograde manner, compressing the intima and ultimately causing “a reverse” secondary intimal rupture in certain cases20. The utility of OCT in the diagnosis of SCAD with intramural haematoma has recently been well described by Saw et al11. In the present instance, the diagnostic confirmation of the intramural haematoma form by OCT also enabled the validation of the relevance of the angiographic signs proposed above (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Spontaneous evolution of SCAD occurring in a 49-year-old woman with coronary artery disease heredity as the sole risk factor. A) Day 0: diffuse and biconcave extrinsic compression of the left anterior descending artery, mimicking a “stick insect” appearance suggesting an intramural haematoma. B) Day 5: evolution to a dissection with radiolucent flap (partial resorption of the parietal haematoma documented in OCT imaged in B1 and B2). C) Late angiographic control at 90 days: complete healing of the artery with disappearance of the parietal haematoma and restoration of the three-layered aspect of the artery, documented in OCT (C1).

Concomitant to intracoronary imaging, we also performed late angiographic controls (in 43 cases), in particular when angiographic ambiguities involved distal or small arteries. The remote angiograms (median delay of 60±39 days) were performed in order to assess the evolution of the dissected arteries.

The spontaneous healing of a large proportion of conservatively managed SCAD has been well observed at late follow-up8,21. At the beginning of the present study, we were not familiar with the angiographic appearance of SCAD associated with intramural haematoma22. Our experience with intracoronary imaging and repeated angiograms enabled us to identify angiographic features specific to SCAD and contributed to the improvement of diagnosis recognition during these last years.

Limitations

This single-centre SCAD series was partially retrospective and relatively limited in terms of size despite being the largest described to date in Europe. The study was conducted in a tertiary coronary care centre; some women with suspected SCAD were referred to our centre by general hospitals, which may have modestly contributed in amplifying the increasing number of SCAD observed in our experience during the last years. Although described very rarely in men (accounting for <10% in the literature20), we did not identify SCAD cases involving men in our cohort. It is plausible that the low clinical suspicion index in this population contributes to an underdiagnosis of SCAD in men and this may therefore constitute a selection bias.

Conclusions

SCAD is a specific entity of ACS and currently underdiagnosed. In the present series, SCAD accounted for approximately one third of women <60 years and with ≤1 CRF presenting with ACS. The combination of specific angiographic features and intracoronary imaging by OCT presented herein facilitates diagnosis and may help clinicians in this setting, particularly in instances of intramural haematoma without intimal rupture.

| Impact on daily practice Spontaneous coronary artery dissection and haematoma (SCAD) is an underdiagnosed entity of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) because of a challenging diagnosis. We highlight specific and original angiographic aspects of SCAD and report a high prevalence of SCAD in women presenting with ACS without cardiovascular risk factors. The combination of specific angiographic features facilitates the diagnosis and may help the clinician confronted with the suspicion of a SCAD diagnosis. |

Conflict of interest statement

P. Motreff and G. Souteyrand declare receiving consulting fees from St. Jude Medical and Terumo. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.