Abstract

Aims: Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an under-recognised and important cause of myocardial infarction in young women. Recurrent SCAD is frequent but poorly understood. We aimed to explore the clinical and angiographic characteristics, and outcomes of recurrent SCAD.

Methods and results: Patients with SCAD extension or recurrence prospectively followed at Vancouver General Hospital were included in this retrospective study. SCAD diagnosis was confirmed by two experienced cardiologists. Detailed medical history, baseline demographics, angiographic results, and clinical details of index SCAD and recurrent events were recorded. SCAD extension was defined as angiographic extension of a previously dissected coronary segment, and de novo recurrent SCAD was defined as new spontaneous dissection. We identified 43 patients with SCAD recurrence with mean age 48.9±8.4 years; 38/43 were women, and 32/43 had fibromuscular dysplasia. Nine patients had SCAD extension at median time of five (1-19) days, while 34 patients had de novo recurrent SCAD at median time of 1,487 (107-6,461) days after the index SCAD event. All SCAD extension patients had worsening of the index dissected segment, with 5/9 involving extension to adjacent segments, while all de novo recurrent SCAD patients had new dissections affecting coronary segments distinct from the index dissection.

Conclusions: De novo recurrent SCAD invariably affected new segments distinct from previously dissected segments.

Abbreviations

ACS: acute coronary syndrome

MACE: major adverse cardiac events

SCAD: spontaneous coronary artery dissection

VGH: Vancouver General Hospital

Introduction

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an important cause of myocardial infarction (MI) in young to middle-aged women, especially in the absence of conventional cardiovascular risk factors1. The utilisation of adjunctive intracoronary imaging with coronary angiography has improved the recognition and diagnosis of SCAD in recent years2-5. The dissemination of new research findings on SCAD together with social media publicity has contributed towards increased awareness of SCAD among clinicians and patients6-11.

The prevalence of SCAD among women presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is noteworthy, with rates reported between 15 and 30% for those aged <60 years old10,12-14. Therefore, a high index of suspicion for SCAD is warranted, especially for young to middle-aged women presenting with ACS. Contemporary series have shown in-hospital mortality <5%, and in-hospital major adverse cardiac events (MACE) including recurrent MI and the need for urgent revascularisation ranging between 5 and 10%1,8,9,15. However, long-term follow-up MACE are quite frequent with reported rates varying between 10 and 20%, predominantly consisting of recurrent MI. In particular, recurrent SCAD events were common, with intermediate-term recurrent rates of 15% within two years, and longer-term recurrent rates as high as 27% at four to five years13.

To date, recurrent SCAD remains understudied, and details including clinical characteristics, angiographic characteristics, and clinical outcomes of recurrent SCAD have not been explored. The majority of published studies were retrospective in nature, and included small patient samples with limited numbers of recurrent events9,16. An improved understanding of the causes and characteristics of recurrent SCAD could provide a basis for the mechanistic understanding of SCAD. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the clinical and angiographic characteristics of recurrent SCAD cases in our large cohort of prospectively followed SCAD patients.

Methods

Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) is a quaternary referral centre for patients with SCAD, and these patients are prospectively followed at our VGH SCAD clinic. Patients with a diagnosis of non-atherosclerotic SCAD confirmed by two experienced angiographers were consented and enrolled in the Non-Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease registry and the Canadian SCAD study, approved by the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board. Detailed medical history, baseline demographic data, laboratory results, angiographic results, and clinical details of the index SCAD event and recurrent events were recorded. Cardiovascular interventions and outcomes, including in-hospital MACE and long-term MACE, were collected. All patients were followed at least annually at our VGH SCAD clinic or by telephone follow-up, and clinical data were entered into dedicated databases. Patients with recurrent events due to angiographically proven extension of SCAD or de novo SCAD events were retrospectively identified from this cohort and included in this study.

The term recurrent SCAD had previously been used to describe two distinct forms of dissection: (1) angiographic extension of a previously dissected coronary segment, or (2) de novo spontaneous dissection unrelated to a previously dissected coronary artery segment. Both forms were associated with clinical evidence of a new recurrent MI (recurrent symptoms and further increase in cardiac enzymes). For the purposes of this study, the former group was classified as SCAD “extension”, and the latter as “de novo” recurrent SCAD. We excluded patients with prior SCAD who subsequently developed recurrent MI secondary to complications related to revascularisation (e.g., stent thrombosis, stent fracture, extension of dissections after stenting) or iatrogenic dissections (i.e., related to trauma or catheter manipulations). Patients with recurrent MI but who did not undergo a repeat coronary angiography were excluded.

All coronary angiograms (from index SCAD and subsequent repeat angiography) from local and referral hospitals were obtained and reviewed by two experienced cardiologists for the diagnosis and classification of SCAD. SCAD was classified according to the previously described Saw classification3. The SCAD coronary segment involved was defined by the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation classification17. Patients were classified as having an early recurrent event if they had recurrent SCAD within 30 days of their index event, or late recurrent event if more than 30 days from their initial presentation. The clinical and angiographic characteristics of recurrent SCAD were documented and compared to the culprit artery at the index SCAD event.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics were utilised to summarise the patient baseline characteristics. Continuous variables were reported as mean±SD, or median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were summarised as frequency and percentage. Comparisons between categorical data were made with the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data were compared using the Student’s t-test. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, Version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

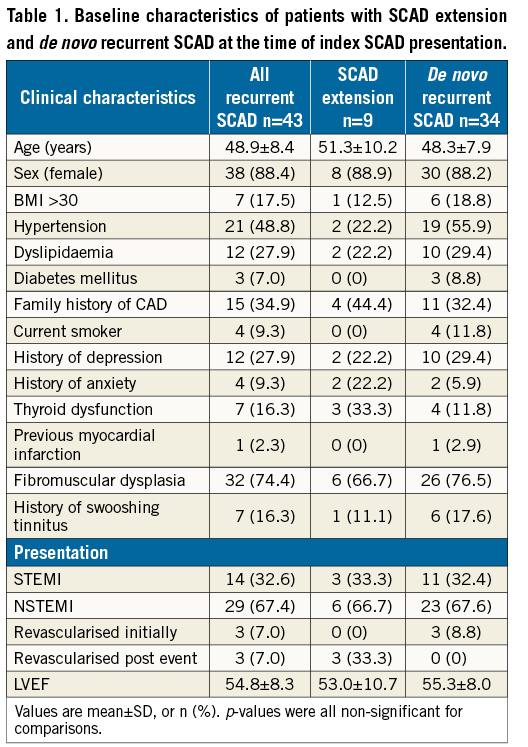

Among our VGH registry cohort of 310 patients with SCAD, there were 43 cases of recurrent events due to extension or de novo recurrent SCAD, with an overall incidence of 13.9%. The baseline characteristics of these patients are described in Table 1, with mean age of 48.9±8.4 years, and the majority being women (38/43; 88.4%). There was a high prevalence of fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) (32/43; 74.4%) and hypertension (21/43; 48.8%). All patients with SCAD and subsequent extension or de novo recurrence presented with troponin-positive ACS.

Extension of SCAD accounted for 9/43 (20.9%) of this cohort, and de novo recurrent SCAD accounted for 34/43 (79.1%). The overall median time to recurrent event with extension of SCAD was five (interquartile range 1, 19) days, and the median time to de novo recurrent SCAD was 1,487 (interquartile range 107, 6,461) days. The clinical characteristics of both groups were similar (Table 1).

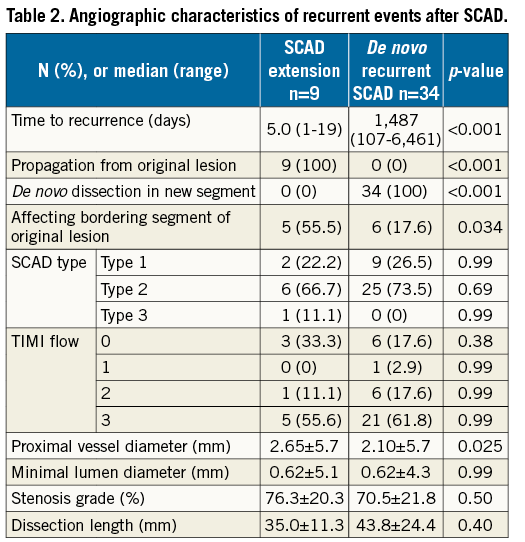

The angiographic characteristics of patients with extension or de novo recurrent SCAD were quite different, and are listed in Table 2. All patients with SCAD extension (n=9) had an early recurrent event within 30 days of initial presentation, with involvement of the same coronary segments as the index SCAD lesion, and five out of nine cases had extension of dissection to a contiguous bordering segment. In contradistinction, all patients with de novo recurrent SCAD had a late recurrent event at >30 days; these de novo dissections affected new coronary segments different from the index SCAD coronary segments (Table 2).

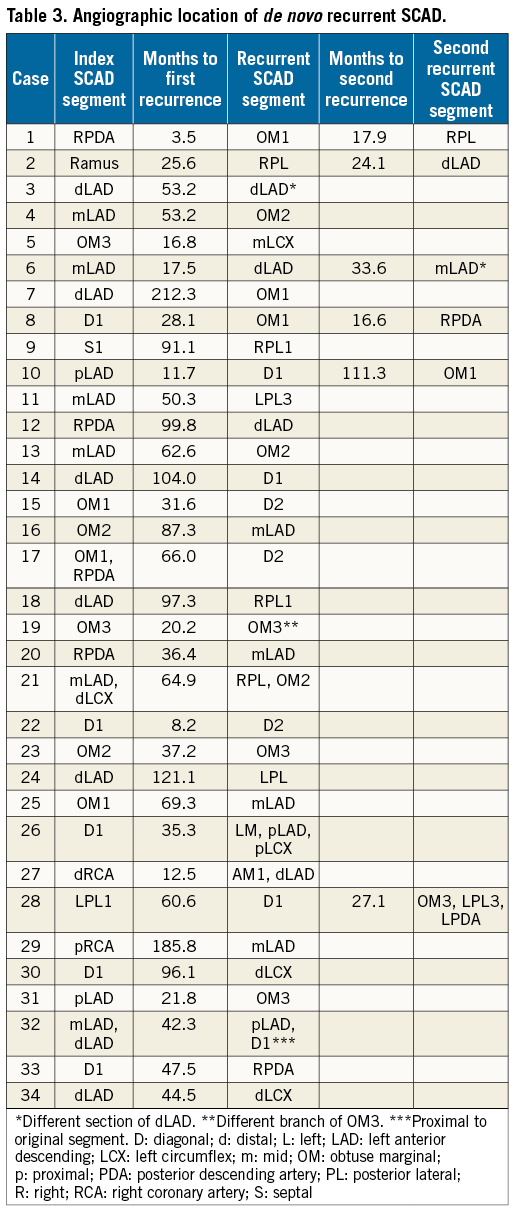

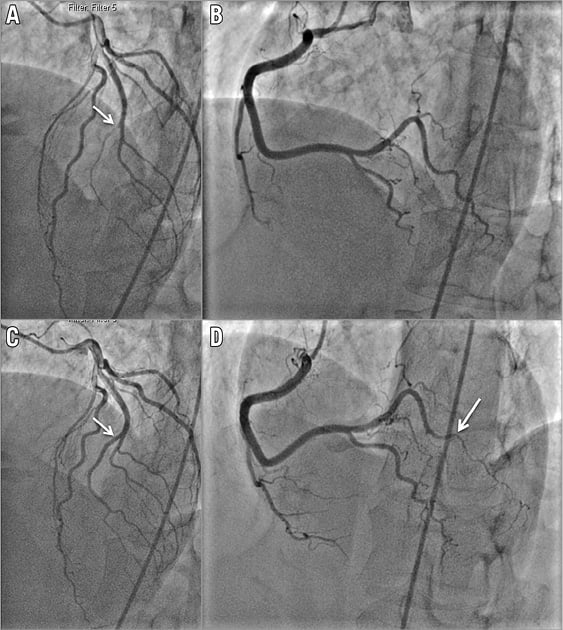

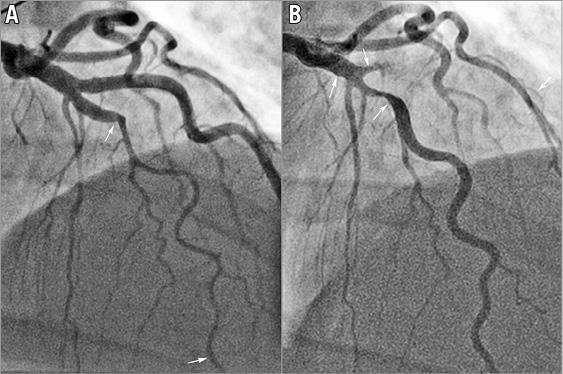

The anatomic location of SCAD at index presentation and subsequent recurrent de novo SCAD are listed in Table 3. All 34 patients had dissections in coronary segments different from the original index dissected coronary segment, and all prior dissected segments had healed angiographically (Figure 1). Even though three patients (cases 3, 19 and 32) developed late de novo recurrent SCAD in the same artery, the recurrent dissections affected new different segments, with the prior SCAD segments showing angiographic healing (but not proven on optical coherence tomography [OCT]). Patient 3 had her index SCAD affecting the distal left anterior descending artery (LAD), and she developed de novo recurrence 53.2 months later, involving a different segment of the distal LAD. Patient 19 had an index SCAD involving the 3rd obtuse marginal (OM) branch, and she re-presented 20.3 months later with de novo recurrence in a different OM3 branch. Patient 32 had her index SCAD involving the mid to distal LAD, and she re-presented four years later with de novo recurrence involving the proximal LAD and a large diagonal branch (Figure 2). Interestingly, in these three cases, the de novo recurrent SCAD involved segments adjacent to the previously dissected artery, but not the healed segment of previous dissections.

Figure 1. Patient 2 with de novo recurrent SCAD. A) SCAD Type 2 of a ramus intermedius branch in 2011 (starting at arrow). B) Normal appearing right posterolateral branch in 2011. C) Angiographic healing of ramus intermedius (arrow) on repeat coronary angiogram in 2013. D) SCAD Type 2 of right posterolateral branch (starting at arrow) in 2013.

Figure 2. Patient 32 with de novo recurrent SCAD. A) SCAD Type 2 of the mid LAD in 2011. B) Angiographic healing in the original segment and recurrent SCAD Type 2 in 2015, proximal to the original segment involving proximal LAD and large diagonal branch.

Six patients (cases 1, 2, 6, 8, 10 and 28) developed a second de novo recurrent SCAD (i.e., 3rd SCAD event). The median time from first recurrence to second recurrence was 21 months. Patient 6 initially presented with SCAD of the mid LAD, her second SCAD occurred 17.5 months later in the distal LAD, and her third SCAD occurred 33.6 months after her second event, involving a different segment of the mid LAD.

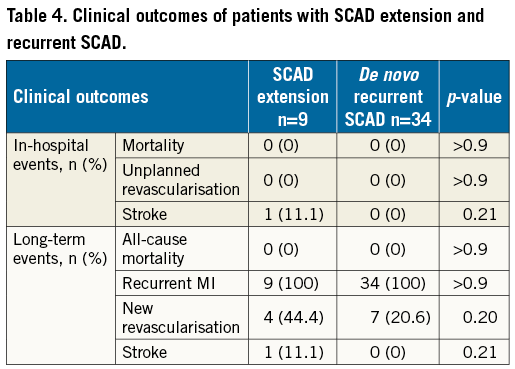

The clinical outcomes of these patients with recurrent events are listed in Table 4. At a median follow-up of 7.96 years (interquartile range 4.5, 11.1), the need for revascularisation occurred in 20.6% in the de novo recurrence cohort, and 44.4% in the extension cohort (p=0.20).

Discussion

We performed a retrospective observational analysis to review the incidence, and clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients with recurrent events due to SCAD extension and de novo recurrent SCAD. SCAD extension or de novo recurrence was common, with an incidence of 13.8%. We found that these two forms of recurrent events were clearly distinct. SCAD extension tended to occur early within 30 days of the index SCAD event, and invariably involved the index SCAD lesion. On the other hand, de novo recurrent SCAD tended to occur much later (beyond 30 days of the prior index SCAD event), and invariably involved a new coronary segment different from the original index SCAD lesion.

The incidence of recurrent events reported in our study is consistent with other studies that reported incidences ranging between 15 and 30% at different durations of follow-up10,17. However, prior studies that reported on “recurrent SCAD” did not differentiate between extension of previously dissected segments, and de novo recurrent SCAD remote from prior SCAD lesions. Based upon the different characteristics that we observed in our current study, we believe that these are disparate events that should be clearly delineated.

Both the timing of recurrent events and the angiographic characteristics were different in these two types of recurrent event. Early recurrent events within 30 days were exclusively related to extension (propagation) of the index SCAD lesion. However, late recurrent events beyond 30 days tended to affect a completely different coronary segment from the index SCAD segment. The differences in timing of events make intuitive sense. One may postulate that early recurrent events tended to be due to the original dissected segments that are still vulnerable to worsening of the dissection from intramural haematoma extension. Interestingly, late de novo recurrent events occurred exclusively in new coronary segments different from the index dissected segment. This is an important and novel observation, and we postulate that arterial wall scarring of a previously dissected segment renders such a segment more resilient to further arterial disruption. Thus, previously healed dissected segments appear to be protected from future recurrent dissection. Indeed, we observed several case examples where de novo recurrent SCAD affected segments immediately adjacent to prior SCAD segments, but explicitly not involving the same previously dissected segment.

The pathophysiology for de novo recurrent SCAD is presumably related to the intrinsic predisposition to arterial fragility in these patients. This, compounded by acute precipitants such as physical and emotional stressors, may trigger a recurrent event. We recently reported that the risk of recurrent SCAD was greater in patients with underlying hypertension, and the use of beta-blockers was associated with lower risk of de novo recurrent SCAD18. The clinical predictors of extension of SCAD have not been adequately explored. In terms of acute management of patients with de novo recurrent SCAD, beta-blockers and dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopiodgrel for one to 12 months) are typically administered, followed by chronic therapy with aspirin and beta-blockers1. With regard to extension of dissection, aspirin and clopidogrel should be administered, and beta-blocker dosage intensified. For patients already on dual antiplatelet therapy, further intensification of antithrombotic therapy is controversial. Heparins, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and thrombolytics should generally be avoided to prevent worsening of intramural haematoma1.

Study limitations

This is a small retrospective observational study of a subgroup of patients with SCAD who experienced recurrent events due to extension or de novo recurrent SCAD. We focused on the clinical and angiographic characteristics that differentiated between SCAD extension and de novo recurrence; however, our findings are hypothesis-generating given the small sample size. There were no pathophysiological data available to support our hypothesis that healed dissected segments are less prone to recurrent dissection. Furthermore, predictors of recurrent SCAD were not investigated in this study, and should be explored in future studies for extension and de novo recurrent SCAD.

Conclusions

Recurrent events after SCAD were common and may be due to early extension of index dissections, or late de novo recurrent dissection remote from index lesions. Future studies should explore the potential cause and prevention of recurrent events after SCAD.

| Impact on daily practice Recurrent SCAD after initial presentation with SCAD is frequent, and may result from dissection extension or de novo recurrent SCAD. Our findings that de novo recurrent SCAD occur at locations distinct from prior SCAD, and are delayed compared to extension of SCAD, can help clinicians to delineate causes of recurrent MI post SCAD. |

Conflict of interest statement

J. Saw has received unrestricted research grant support (from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada, University of British Columbia Division of Cardiology, AstraZeneca, Abbott Vascular, St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, and Servier), speaker honoraria (AstraZeneca, St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, and Sunovion), consultancy and advisory board honoraria (AstraZeneca, St. Jude Medical, and Abbott Vascular), and proctorship honoraria (St. Jude Medical and Boston Scientific). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.