Abstract

Aims: The aim of this study was to report our experience with the Cook Formula stent in the treatment of (recurrent) coarctation of the aorta in children below 12 kg.

Methods and results: In vitro study of the Cook Formula 418 (8 mm) and 535 (8 and 10 mm) stents demonstrated successful down-crimping on smaller balloons and predictable fracturing patterns. Between November 2012 and January 2019, one patient with native, one patient with post-interventional and thirteen patients with post-surgical coarctation of the aorta underwent implantation of a Cook Formula stent. Patient and procedural characteristics were obtained as well as procedural success, complications, and follow-up. Median age was 4.3 months and median weight 5.5 kg. Arterial sheath size ranged from 5 to 7 Fr. In-stent diameters of 3.7 to 8.8 mm were obtained with a median residual gradient of 0 mmHg. Major complications consisted of periprocedural haemodynamic instability (n=1), dissection of the iliac artery (n=1) and non-deployment with surgical removal (n=1). Re-dilations were performed after a median interval of 24.3 months. Median follow-up was 31.7 months.

Conclusions: The bare metal Cook Formula stent provides a durable and effective alternative to reoperation and balloon dilatation for native as well as post-surgical aortic coarctation in children below 12 kg.

Introduction

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a relatively common congenital heart defect with an incidence of 0.3-0.4 per 1,000 live births1,2,3. It comprises a heterogeneous group of lesions characterised by narrowing of the thoracic aorta, sometimes presenting as an isolated lesion but frequently occurring in conjunction with other congenital cardiac abnormalities ranging from a bicuspid aortic valve to hypoplastic left heart syndrome4,5,6,7.

Surgical correction is the gold standard in infants8. However, 5-24% of patients receiving successful surgery present with recurrent coarctation of the aorta (ReCoA) at midterm follow-up and need additional treatment9,10,11,12,13. Balloon angioplasty (BA) is considered less invasive but is associated with a risk of aneurysm formation and higher recurrence rates14,15.

During the past two decades, stent implantation has emerged as a therapeutic alternative to surgery and BA in ReCoA in adults and older children. Nevertheless, stent implantation remains a controversial strategy in infants below 15 kg due to relatively large sheath dimensions as well as the inability to accommodate adult vessel sizes after somatic growth. Small-size stents, specifically developed for infants with CoA, show low radial strength and early re-obstruction. Bioabsorbable stents that would not necessitate removal need relatively large sheaths, achieve small diameters only and are currently not commercially available for clinical use16,17,18,19,20. The Cook Formula bare metal stent is promising since it can be reliably overdilated with minimal shortening and excellent radial strength21.

The aim of this study is to report on our in vitro and in vivo experience with the bare metal Cook Formula® stent (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) in small children with early ReCoA after initial surgery or with native CoA unsuitable for surgery and BA.

Methods

A retrospective single-centre study was performed evaluating the concept of interventional treatment with Cook Formula 418 and 535 stents in infants below 12 kg with ReCoA or with native CoA unsuitable for surgery or BA. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Review Board of the University Medical Centre Utrecht. The definition of CoA was a narrowing of ≥50% at the level of CoA and/or an invasive systolic pressure gradient (dP) ≥20 mm. Interventional treatment was performed if (Re)CoA was associated with a dP ≥20 mm, left or right ventricular dysfunction, and if aneurysm or dissection was highly suspected.

The Cook Formula 418 and 535 stents are identical bare metal, premounted, balloon-expandable stents brought to the European market in 2012. They are available in various diameters (4 to 10 mm) and lengths (12 to 50 mm) and are compatible with a 0.018” (418) or 0.035” (535) guidewire.

BENCH TEST

Bench testing of the 8 mm and 10 mm diameter stents was carried out using non-compliant Atlas® ultra-high-pressure balloons (Bard Peripheral Vascular, Tempe, AZ, USA). The stents were tested for down-crimping on Cook Advance® balloons (Cook Medical) of a smaller diameter than the nominal diameter and fractured with Atlas balloons with specific attention to dilation and fracturing patterns.

INTERVENTION

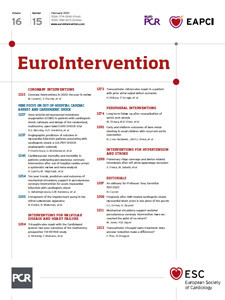

After bench testing, the stents were applied in the clinical setting. All parents were informed about the stent characteristics, need for redilation during somatic growth and the necessity of stent breaking at an older age; they gave informed consent for the procedure. Patient characteristics, indication for intervention and follow-up data were retrospectively retrieved from patient charts. Echocardiography (echo) and four limb arterial blood pressure (ABP) measurements were obtained in all patients pre and post intervention. Interventions were carried out under general anaesthesia. Aortic morphology was visualised using biplane angiography and/or three-dimensional rotational angiography (3DRA) in an Artis zee system with syngo DynaCT (Siemens, Forchheim, Germany) (Figure 1). Only 8 and 10 mm stents were used; they were down-crimped on smaller Cook Advance balloons if necessary.

Figure 1. Three-dimensional rotational angiography (3DRA) imaging. A) 3DRA pre-intervention: aorta in silver, pigtail catheter in red. B) 3DRA post-intervention: aorta in yellow, stent and pigtail catheter in blue.

Stents were delivered through a 5-7 Fr long sheath (Flexor®; Cook Medical). After repeat haemodynamic and angiographic evaluation, sheath and wires were withdrawn and manual haemostasis was applied. All patients received heparin (therapeutic dose of 100 IU/kg) and antibiotics (prophylactic dose). Prophylactic antiplatelet drugs (acetylsalicylic acid 3-5 mg/kg/day) were prescribed if the in-stent diameter was <8 mm. Post-interventional recovery of the femoral artery was monitored by pulse oximetry.

Over time, several adaptations were implemented. After initial diagnostics via a 4 Fr short sheath, an iliac angiography had to demonstrate sufficient size and exclude previous damage to the femoral arteries before the 5-7 Fr long sheath was introduced. This long sheath was kept in situ for as short a time as possible and immediately changed back to the standard 4 Fr short sheath after stent implantation. Clopidogrel was added to the post-intervention antiplatelet regime in 2013.

FOLLOW-UP

Standard follow-up included pulse oximetry at both feet, four limb ABP measurements and echo before discharge and one to two weeks after the procedure. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) was performed if aneurysm formation was suspected. Procedure-related adverse events were defined as aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm, neointimal proliferation, stent fracture, stent migration, peripheral complications and death; occurrence was retrieved from patient charts. Last follow-up was defined as the date of last clinical evaluation with imaging (echo, CTA) or catheterisation.

DATA ACCESS

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study.

Results

BENCHMARK TESTING

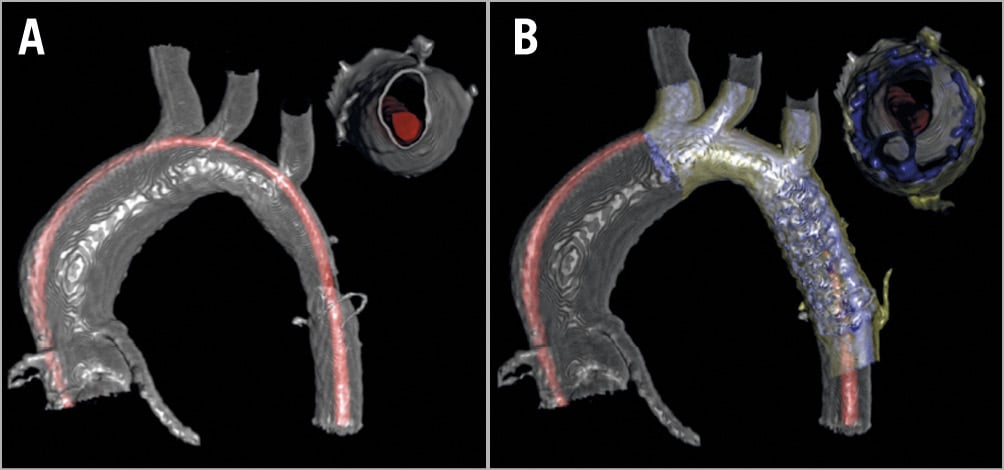

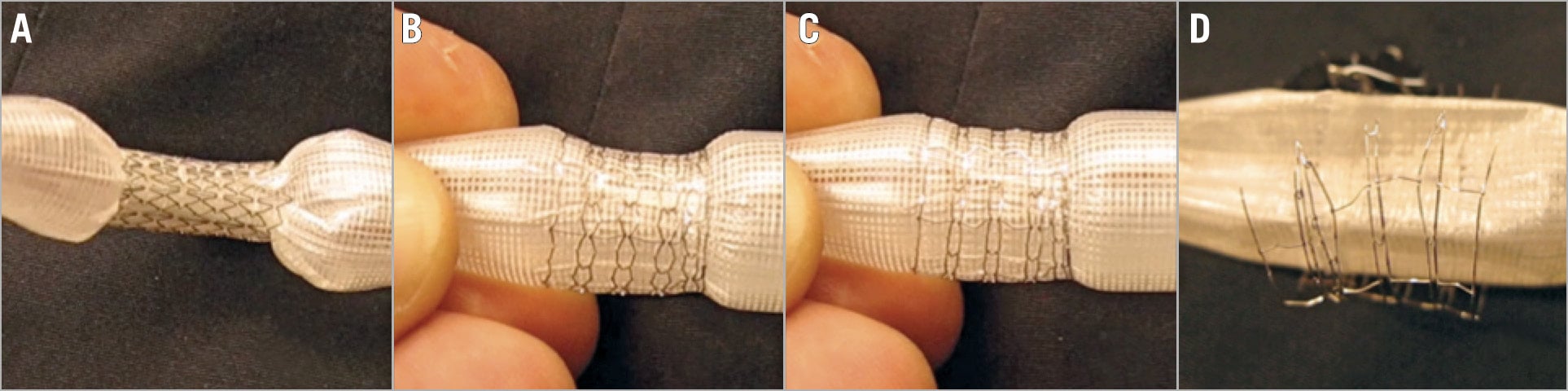

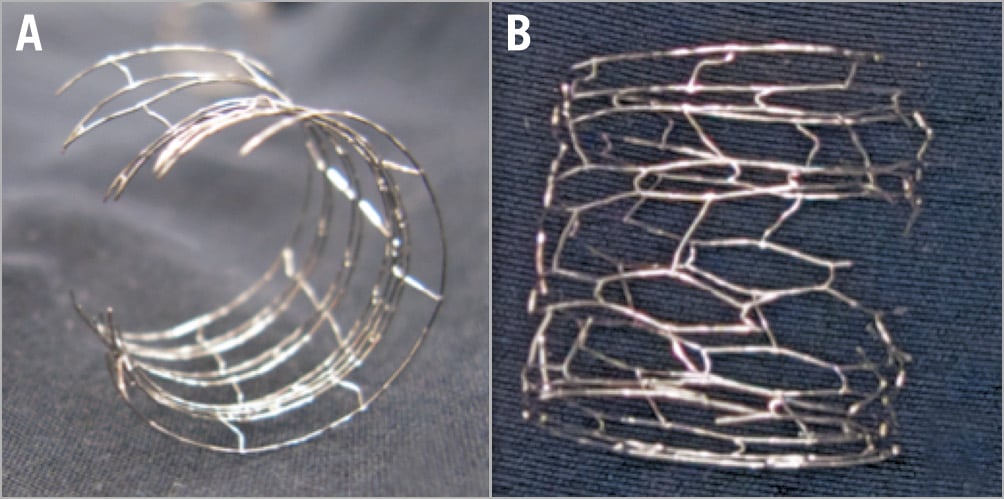

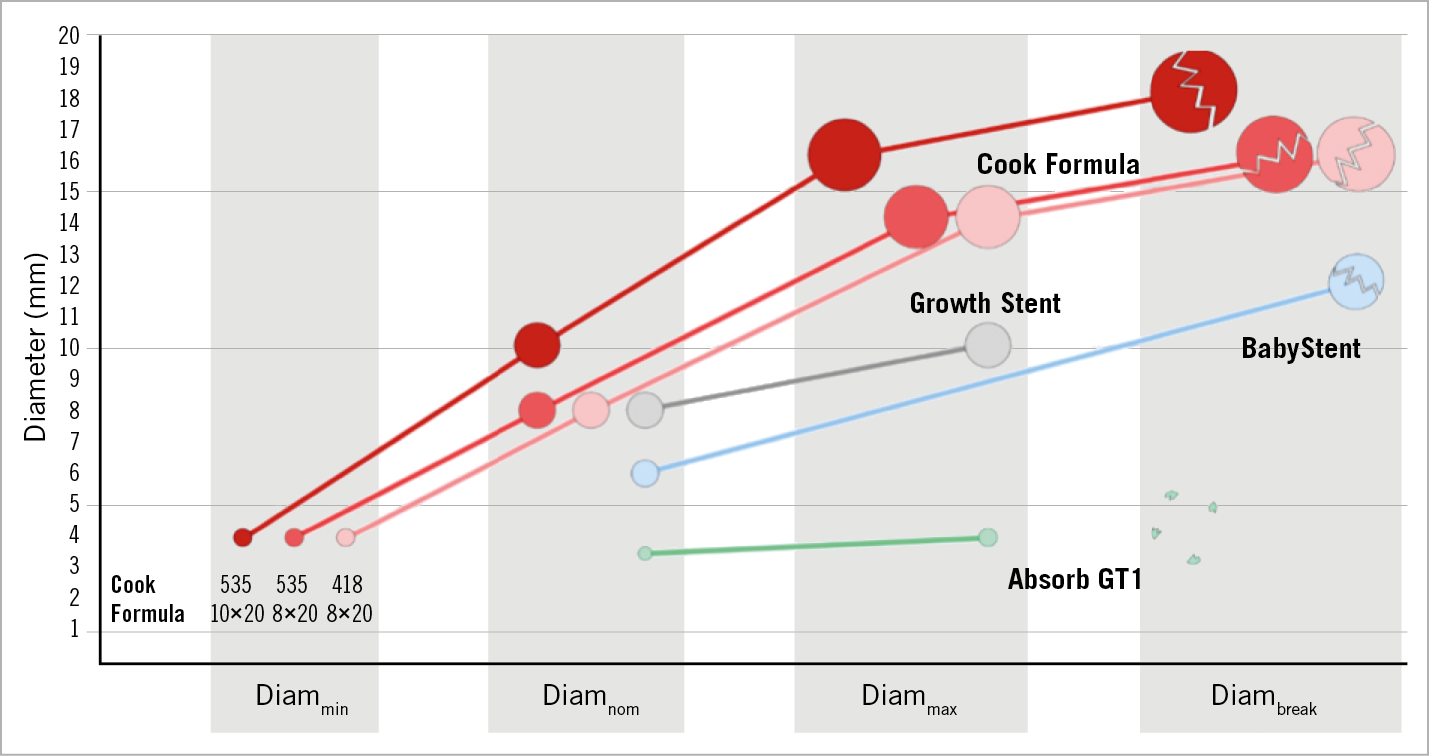

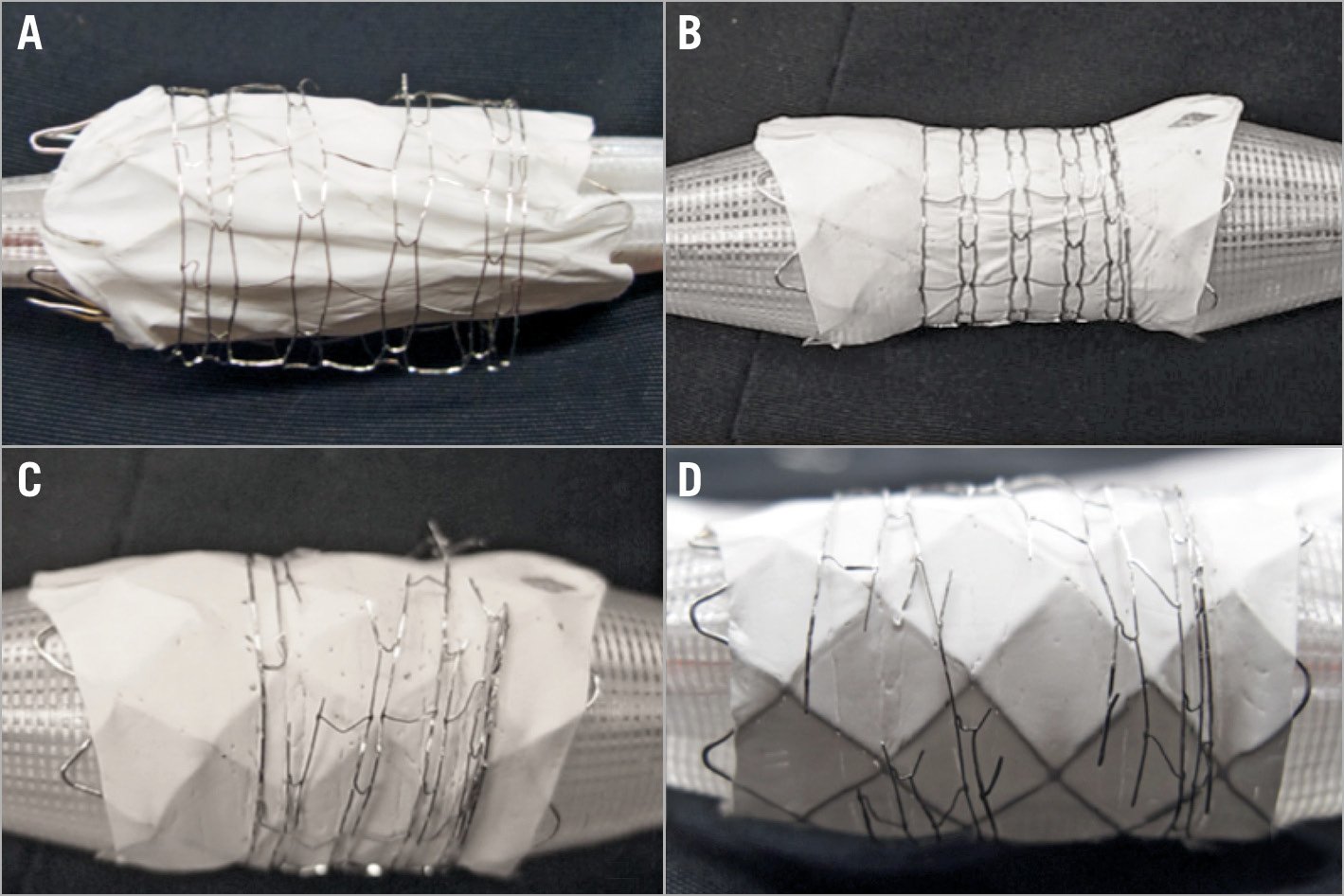

Benchmark testing showed that the 8 mm and 10 mm Cook Formula stents could be overdilated up to 16 and 18 mm diameter, respectively, with little foreshortening. Longitudinal fracturing was accomplished with an Atlas balloon 2-4 mm larger than the maximum diameter (Figure 2). Fracturing resulted in a circular open stent shape (Figure 3). The bench test results are displayed in Figure 4. They are compared to the characteristics of the BabyStent® (OSYPKA AG, Rheinfelden, Germany), Growth Stent® (QualiMed, Winsen/Luhe, Germany) and Absorb™ GT1 (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA)16,17,18,20,21. An in vitro simulation of our “stent-in-stent” procedure was also performed (Figure 5).

Figure 2. Bench testing of a Cook Formula 535 (10×20 mm) stent mounted on an 18 mm diameter Atlas balloon. A) Dilation up to nominal diameter. B) Overdilation to maximum diameter with little foreshortening. C) Maximal outlining of radial rings. D) Fracture with preservation of the circular shape.

Figure 3. Stent fracture of a Cook Formula 535 (10×20 mm) stent. All struts are horizontally fractured after overdilation with an Atlas 18 to 22 mm diameter balloon. The circular stent shape was preserved.

Figure 4. Overview of stents tested for coarctation in young children. Stent characteristics during dilation are shown: minimal diameter (Diammin), nominal diameter (Diamnom), maximum diameter (Diammax) and diameter at fracture (Diambreak). Stents are displayed in real proportion.

Figure 5. Stent-in-stent fracturing. A Cheatham Platinum covered stent is mounted on an 18 mm Atlas balloon and introduced in a Cook Formula 535 (10×20 mm) stent (A) with subsequent dilation to 16 mm (B) and controlled fracturing (C & D) of the outer Cook Formula 535 stent.

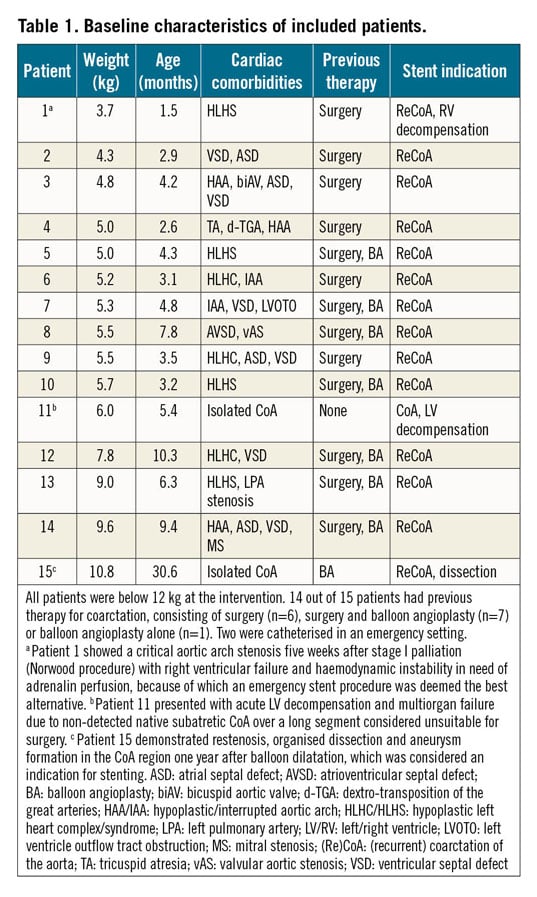

PATIENTS

Between November 2012 and January 2019, 15 patients were considered eligible for Cook Formula stent placement in the aortic arch. All but one patient presented with ReCoA after primary treatment consisting of surgery and/or BA in conformity with the accepted guidelines. One case of native CoA was treated with stenting because surgery was considered unsuitable due to haemodynamic instability. The patients had a median body weight of 5.5 kg (3.7-10.8) and median age of 4.3 months (1.5-30.6). Median time interval between primary treatment and stenting was 3.5 months (1.2-11.9). All patients with previous surgery (n=13) had a patch angioplasty. Other baseline characteristics are described in Table 1.

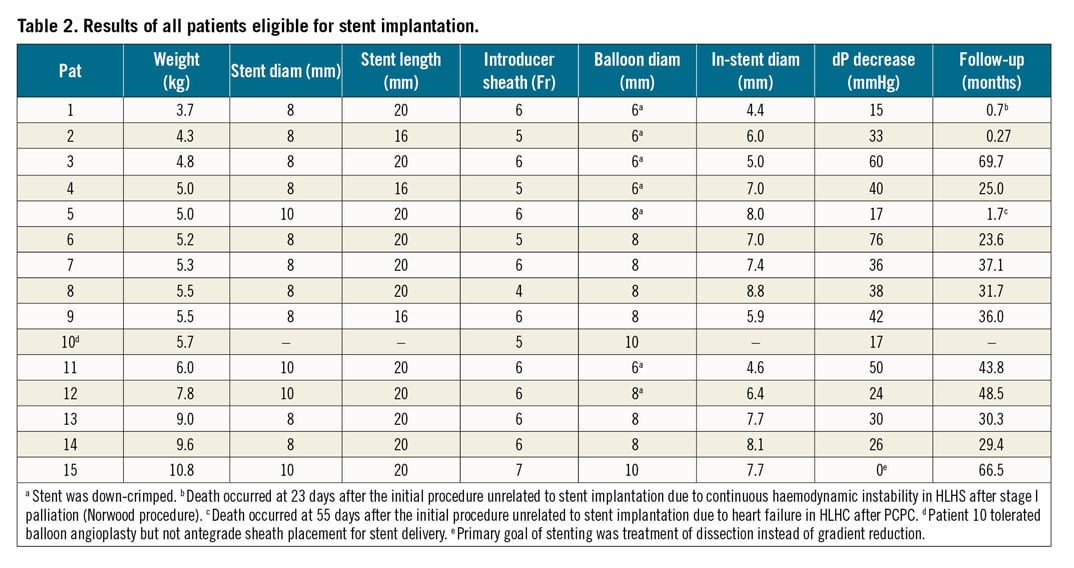

INTERVENTION

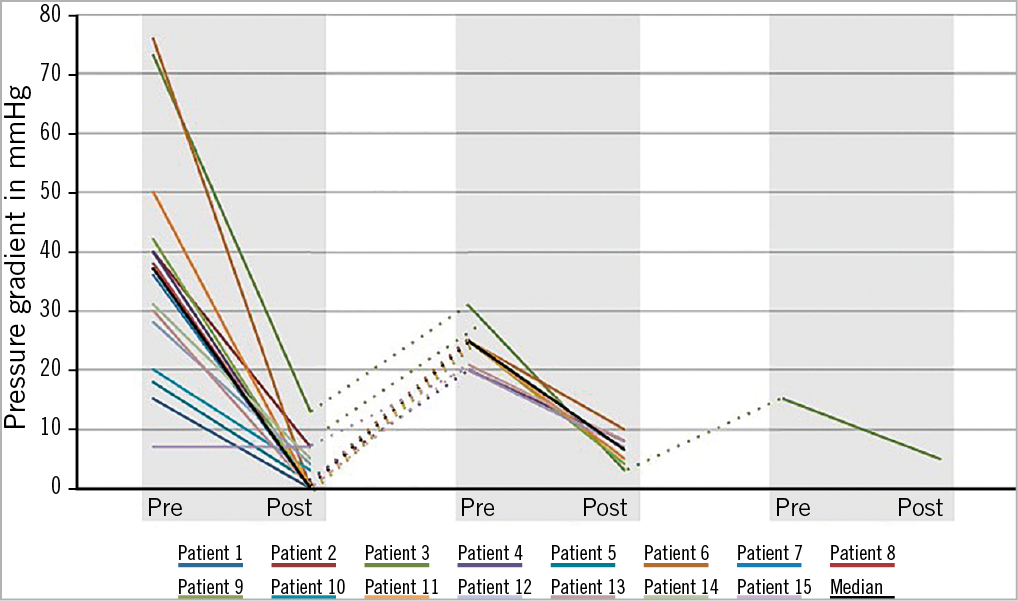

Results are displayed in Table 2 and Figure 6. All but one procedure was successful with adequate gradient reduction. Antegrade sheath implantation was not tolerated due to haemodynamic instability in one patient after single ventricle stage I palliation. The stent was advanced without a sheath over a wire but could not be delivered past the tricuspid valve. It was then retracted into the left femoral vein and surgically removed. This patient was excluded from further follow-up.

Figure 6. Gradient reduction in patients at initial catheterisation and redilation. Stenting provides an immediate decrease of the pressure gradient and can be performed repeatedly in case of somatic growth. Patient 10 did not receive a Cook Formula stent because of periprocedural haemodynamic instability; instead, gradient reduction was realised by ballooning.

The stent dimensions were 8 mm or 10 mm nominal diameter with a length of 16 or 20 mm. Smaller stents were not used to ensure larger growth potential. The down-crimping technique, in which the Cook Formula stent was taken from its original balloon and placed onto a Cook Advance balloon, was used in seven procedures. The smallest balloon used for implantation was 6 mm in diameter and was introduced over a 0.018” wire.

After stent implantation, aortic diameter increased from median 2.5 mm (1.0-6.7) to median 7.0 mm (3.7-8.8). Invasive dP decreased from median 36 mmHg (7-76) to median 0 mmHg (0-13); the median decrease was 33 mmHg (0-76). Intima injury of the iliac artery occurred in our smallest patient of 3.7 kg body weight during withdrawal of the 5 Fr long sheath and was treated conservatively with prothrombin infusion and back-up of a coronary guidewire in situ.

FOLLOW-UP

Follow-up was performed until January 2019. Median follow-up after stent implantation was 31.0 months (0.3-69.7). No patients were lost to follow-up. All patients maintained a pulsatile flow in the abdominal aorta, except for patient 1. This was explained by right ventricular failure after stage I palliation (Norwood procedure). Mild intima proliferation was found during seven out of eight redilation procedures, primarily at the proximal stent. Right femoral artery stenosis was found in one patient at redilation despite pulsatile flow at discharge. CTA imaging was performed in two patients because echocardiographic findings were suspect for dissection, but no dissection was found. Death occurred in two patients due to severe cardiac failure at 23 days and 55 days after the initial procedure, unrelated to the stenting.

After a median time of 24.3 months (3-40), eight redilation procedures were performed in seven patients. Freedom from reintervention was 29.4 months (0.3-48.5) in the remaining seven patients. The indication for redilation was ReCoA due to somatic growth in all patients. Of these redilations, three were performed during a routine pre-partial cavopulmonary connection (PCPC) or pre-total cavopulmonary connection (TCPC) evaluation. Peak dP decreased from median 23 mmHg (15-31) to 6 mmHg (3-10). Median gradient decrease was 15 mmHg. There were no interventional complications during redilation. Overdilation and breaking of stents have not been necessary in our (Re)CoA population so far.

Discussion

This paper is the first to describe the use of Cook Formula stents in (Re)CoA in children below 12 kg. This study demonstrates that (Re)CoA can be successfully treated with the Cook Formula stent with a low rate of complications and reliable freedom from ReCoA. Nevertheless, serial redilation of the stents remains necessary due to somatic growth.

ReCoA is a common complication after both surgery and BA for CoA relief22. Reoperation in post-surgical CoA often requires median thoracotomy and is associated with higher initial cost and longer hospital stay compared to BA23,24. However, ballooning is reported to have a higher incidence of ReCoA recurrence, femoral artery injuries and aortic aneurysms23. Percutaneous stent insertion could be a favourable option in infants if the need for surgical removal due to somatic growth can be avoided, but is currently not considered standard practice8. In addition, it is important to remain aware of the long-term risks of ionising radiation. A recent long-term follow-up study described palliative stenting of native CoA in three patients below 9 kg. It demonstrated adequate short-term relief as well as successful application of a “stent-in-stent” dilation procedure in two patients, reaching adult aortic diameters after somatic growth25.

Recent advances in stent technology have resulted in stents with lower profiles and a wider range of diameters. Unfortunately, all available stents show significant limitations. Different small-size stents were developed to be implanted in infants with CoA such as the BabyStent (4 Fr sheath) and the Growth Stent (5 Fr sheath). The BabyStent is constructed of bare metal with overall minimised material thickness. Frequent redilations were encountered in a very limited follow-up period16. The Growth Stent consists of two longitudinal halves with large cells connected with bioabsorbable sutures to create a circular structure. Low radial strength and intimal folding through cells caused intimal proliferation and early re-obstruction17. Commercially available bioabsorbable stents so far have not proved to be an alternative due to small diameters, low radial strength and scaffold thromboembolic complications and are therefore not available for clinical use26. Unlike these aforementioned alternatives, the Cook Formula stent integrates higher radial strength and greater growth potential with smaller sheath sizes appropriate for young children.

We propose a two-stage approach starting with implantation of a bare metal stent of 8 to 10 mm diameter overdilatable up to 16 to 18 mm in early infancy. This corresponds to the aortic diameter at 30 to 40 kg body weight. If, at implantation, a stent diameter of less than 8 mm is required to fit the patient, the stent is taken off its original balloon and down-crimped on a smaller Cook Advance balloon (i.e., 6 mm) to preserve the benefit of a larger maximum diameter in the future. We stock the BeGraft Peripheral stent with ePTFE covering and diameters ranging from 5 to 10 mm (Bentley InnoMed, Hechingen, Germany) as back-up in case of interventional complications such as aortic dissection or aneurysm formation. Before the arrival of the BeGraft Peripheral covered stent, Cheatham Platinum (CP; NuMED Inc., Hopkinton, NY, USA) and Atrium Advanta™ V12 (Atrium Europe B.V., Mijdrecht, the Netherlands) stents were available for bail-out. Their use has not been necessary up to now in CoA below 12 kg. The maximum achievable diameter of 12 mm (nominal diameter plus 2 mm) is a major limitation for primary use in small children. Nevertheless, bench testing of the BeGraft stents proved good fracture characteristics comparable to those of the Cook Formula stent (results not shown).

When a Cook Formula stent reaches its maximum diameter of 16 or 18 mm, a “stent-in-stent” breaking procedure can be performed with a covered stent inside (i.e., covered CP stent) and an Atlas balloon of 18 or 20 mm, respectively. Controlled radial fracturing with little foreshortening was achieved in vitro with an Atlas balloon not more than 2-4 mm larger than the Formula stent. Assuming that the in vivo characteristics correspond with the in vitro behaviour, a solely intervention-based approach could be realised without the need for reoperation from early infancy to adulthood. Although in vivo stent breaking has not been indicated in our ReCoA patients so far, it has been performed successfully in our centre in two patients with left pulmonary artery stenting. This experience confirms the promising two-step approach.

Stenting of (Re)CoA in these small infants is neither routine nor standard. Therefore, we critically optimised our workflow to target the largest diameter with lowest vessel trauma. It is acknowledged that large long sheaths severely overstretch the femoral and iliac arteries. Hydrophilic coated sheaths may seem beneficial but in fact cause strong adhesion instead if the thin lubricating blood layer disappears due to overstretching of the vessel. We advise non-hydrophilic long sheaths and stepwise withdrawal accompanied by angiographies and careful attention to friction. Minimising the in situ time of the implantation sheath by exchanging it for the initial 4 Fr short sheath immediately after intervention is a high priority. Finally, a small guidewire left in situ will preserve immediate access in case of dissection or rupture.

The use of 3DRA adds multiple advantages. Performed as start-up imaging it offers visualisation of the aortic arch and (Re)CoA in high spatial resolution. Cross-sectional and virtual endoscopic views allow precise identification of stenosis. Aortic dissection or aneurysm formation can be visualised with 3DRA during the procedure with high accuracy not obtainable by two-dimensional imaging. 3D road mapping helps to guide stent implantation and enables lower doses of radiation and contrast.

Limitations

This study is limited due to the absence of a BA control group and the small single-centre population. However, to our knowledge, this retrospective case series of 15 patients is the largest published on the use of bare metal stents in (Re)CoA below a weight of 12 kg. The results show that stent implantation in early (Re)CoA is a safe treatment with an acceptable rate of complications and reintervention in these small infants. Our expectation is that a stent-in-stent approach will obviate the need for surgery after early stent implantation and allow an intervention-based follow-up of this population. Therefore, bare metal stenting seems to be a promising, less invasive alternative to redo surgery. Nevertheless, availability of local expertise should always be considered when determining the preferred treatment in each individual patient.

Conclusions

The bare metal Cook Formula stent provides a durable and effective alternative to reoperation and balloon dilatation for native as well as post-surgical aortic coarctation in children below 12 kg. The proposed two-stage method of redilation and stent-in-stent fracturing facilitates an entirely interventional approach.

|

Impact on daily practice Stenting of aortic coarctation in children below 12 kg is feasible when surgery is unattractive and balloon angioplasty is not desirable. Accommodation for somatic growth can be realised by serial redilation and stent-in-stent fracturing. |

Conflict of interest statement

G. Krings reports receiving grants and personal fees from the Advisory Board at Siemens (member) and being a consultant for Edwards. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.