Abstract

Aims: This study aimed to provide a simple index for predicting the definitive indication for transcatheter closure of atrial septal defect (ASD) with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

Methods and results: A positive response after attempted occlusion was defined as mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP) ≤30 mmHg or the decrement percentage of it ≥20% compared with baseline. If a positive response was achieved, the occluder would be released, and the procedure was defined as successful. In 209 patients who underwent a successful procedure without PAH-specific medicine, there was a dramatic decrease in the percentage of patients with pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP) ≥50 mmHg from baseline to the one-year follow-up (79.4% to 14.0%, p<0.001). The optimal cut-off value of MPAP to predict a positive response without PAH-specific medicine was 35.0 mmHg, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.919 (p<0.001). Administration of inhaled iloprost extended the cut-off point to 50.0 mmHg to reach a positive response, with an AUC of 0.774 (p=0.003).

Conclusions: This large-scale study indicated that MPAP could be a simple but powerful index to predict benefit from closure in adult ASD patients with PAH.

Introduction

The development of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is frequent in adult patients with atrial septal defect (ASD). Approximately 6% to 35% of patients with secundum ASD have PAH1,2,3. These patients are at higher risk of mortality, functional limitations and atrial tachyarrhythmias4,5. Some reports have observed that transcatheter closure in patients with secundum ASD and PAH could be associated with good outcomes6,7. However, other studies found that PAH may still be progressive even after ASD device closure3,8. For some patients, e.g., with right to left (R-L) shunt and/or need for decompression, closure of ASD is even contraindicated9. There is consensus that some ASD patients with PAH will benefit from closure9, but the definitive indication for transcatheter closure of ASD with PAH remains controversial.

The Qp/Qs ratio and pulmonary vascular resistance are the most important reference indices regarding the indication for ASD closure in current guidelines9. However, these are complicated to calculate and the evidence is old and poor3,9,10. Adult ASD patients with PAH are more common in developing countries such as China11. We treated a large number of ASD patients with PAH in our centre and guessed that mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP) might be a simpler index regarding eligibility for ASD closure, based on our past clinical experience. This study aimed to test our proposed indication for permanent closure and give an optimal cut-off value of a simple index (MPAP) for predicting this indication in a large cohort of ASD patients with PAH.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

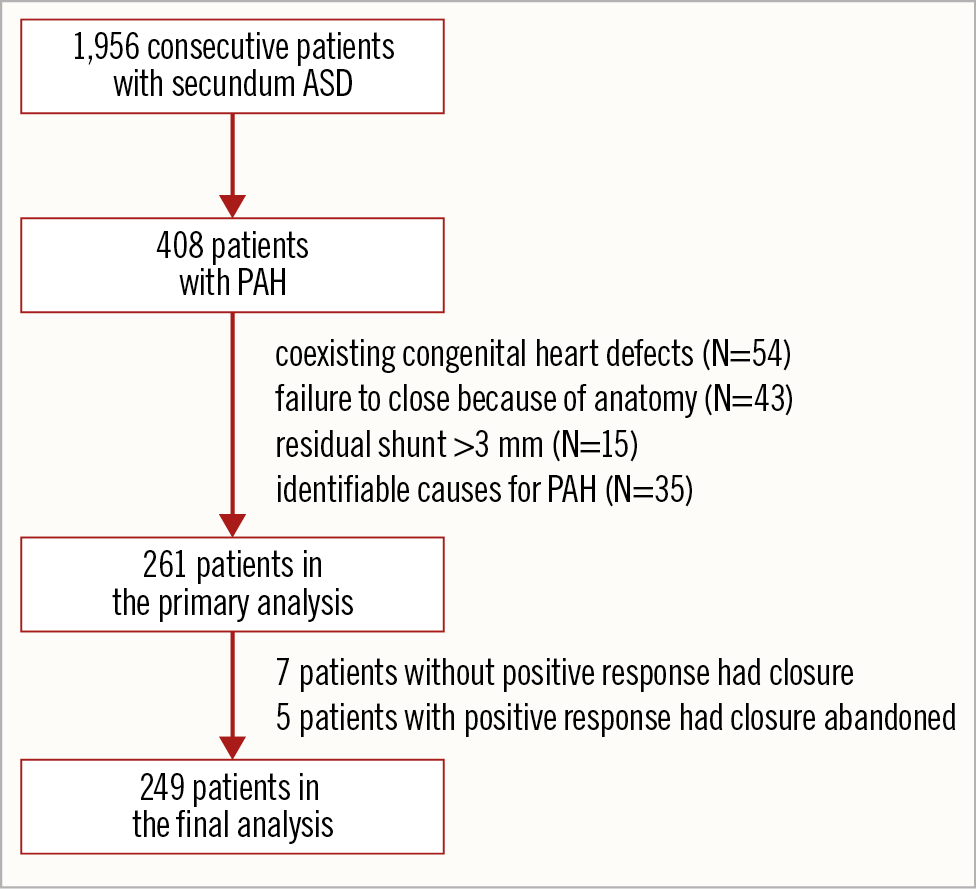

The study retrospectively analysed the data of patients with ASD and PAH who underwent attempted transcatheter closure between December 2013 and December 2016. During the period, there were 1,956 consecutive patients with secundum ASD referred to our centre for transcatheter closure. There were 408 patients with pulmonary hypertension, defined as MPAP ≥25 mmHg by catheterisation. However, those patients were subsequently excluded if there were other coexisting congenital heart defects (N=54), residual shunt >3 mm (N=15), failure to close because of anatomy (N=43), or identifiable causes for PAH (N=35), including mitral valve disease, a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%, pulmonary thromboembolic disease, severe lung disease with hypoxaemia, portal hypertension, or obstructive sleep apnoea. Thus, 261 ASD patients with PAH who underwent attempted transcatheter closure of ASD were enrolled in the primary analysis. Among the 261 patients, seven patients who did not meet the positive response criterion had the defect closed, and closure was abandoned for five patients who met the positive response criterion. These 12 patients were excluded; consequently, 249 patients were included in the final analysis. The flow chart of patient selection is shown in Figure 1. The study was conducted in accordance with the institutional Human Subjects Committee guidelines and approved by the local institutional review board. Because this was an observational study and all indices observed were commonly measured for all patients in our clinical practice, the need for written informed consent was waived by the ethical review board.

Figure 1. Flow chart of patient selection. ASD: atrial septal defect; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension

ATTEMPTED OCCLUSION AND DEFINITION OF A POSITIVE RESPONSE

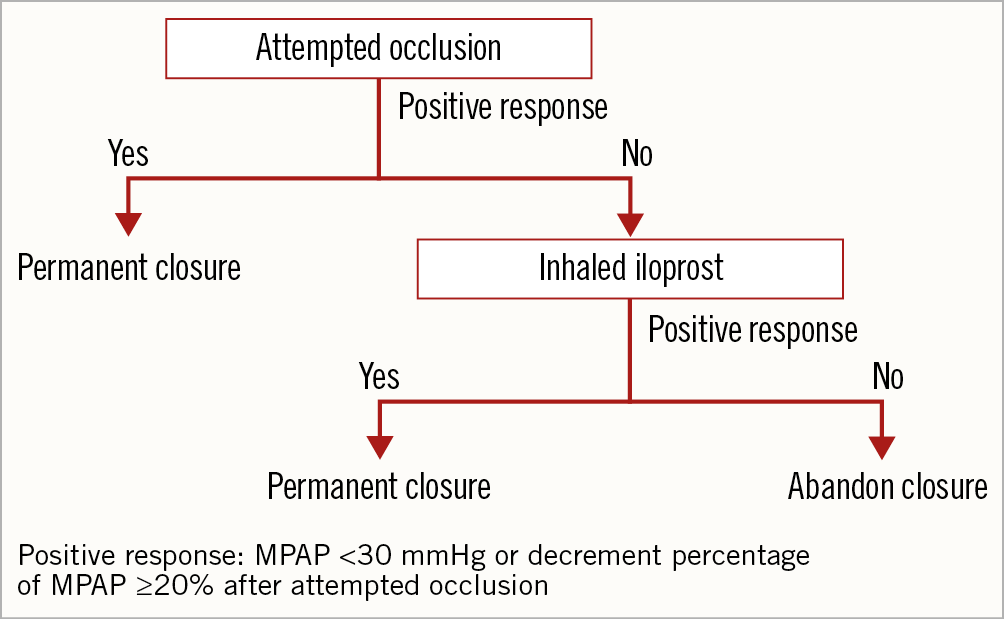

Transcatheter ASD closure was performed under local anaesthesia with fluoroscopic and transthoracic echocardiographic guidance. The procedures were conducted using Amplatzer-like domestic septal occluders (Lifetech, Shenzhen, China; SHSMA, Shanghai, China; or Starway Medical Technology, Beijing, China). The flow chart of attempted occlusions is shown in Figure 2. In our centre, a positive response to attempted occlusion was defined as the absolute value of MPAP ≤30 mmHg or the decrement percentage of it ≥20% compared with baseline immediately (five minutes) after attempted occlusion, without a decrease of the mean peripheral blood pressure (<10%) or an increase in the ventricular end-diastolic pressure (<10%). If a positive response was achieved, the occluder would be released. When a positive response was not reached (defined as a negative response) after attempted occlusion, inhaled iloprost was given. Inhaled iloprost was administered via a nebuliser (with a mouthpiece) at a cumulative dose of 20 µg for a total duration of 10 minutes. The MPAP was then assessed again. If a positive response was attained, the patent’s ASD would also be permanently closed. Otherwise, the closure would be abandoned. An increase in MPAP or right ventricular filling pressures or a drop in cardiac output suggests a low likelihood of benefiting from permanent closure. Even if the MPAP declined but the percentage of decrement was less than 20% and MPAP ≥30 mmHg, permanent closure was still abandoned. In this study, if a positive response was achieved with or without inhaled iloprost, the ASD would be permanently closed, and the procedure was defined as successful. On the other hand, if a positive response could not be achieved even with inhaled iloprost, the closure would be abandoned, and the closure was defined as unsuccessful. Additionally, patients who had a residual shunt >3 mm and in whom closure failed because of anatomy were excluded from the study. Thus, they were not included in the unsuccessful closure group.

Figure 2. Flow chart of attempted occlusion in our centre.

CLINICAL VARIABLES AND FOLLOW-UP

Data collection was performed retrospectively. Baseline clinical data included age, gender, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, history of atrial arrhythmia and associated comorbidities. Oral PAH-specific medicine was generally given for three to six months for the patients with successful closure with the inhaled iloprost. Transthoracic echocardiography was regularly performed in all ASD patients undergoing transcatheter closure before the procedure, before discharge and at three months and one year after the procedure. The maximum diameter of the ASD, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP), and degree of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) were assessed by transthoracic echocardiography. TR was quantified by colour Doppler imaging. PASP was derived from right ventricular systolic pressure estimates using the tricuspid regurgitation velocity (V) and the Bernoulli equation as 4V² + right atrial pressure12. A PASP measured by echocardiography ≥50 mmHg was regarded as PAH in this study according to the ESC guidelines13.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean±SD. Categorical variables are reported as the frequency and percentage. Normal distribution was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Comparisons of continuous variables between different groups were performed by univariate analysis of variance, followed by a Bonferroni correction post hoc test when applicable. Comparisons of continuous variables between different time points within one group were performed with the paired Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) methodology was used to analyse the optimal cut-off value of MPAP by catheterisation in predicting a positive response without PAH-specific medicine for all enrolled patients. In addition, we performed the ROC analyses again for the patients in whom an attempted closure failed at first but who then received inhaled iloprost to determine the optimal cut-off value of MPAP by catheterisation. ROC analyses are expressed as curve plots and calculated area under the curve (AUC), with the confidence interval (CI) and the associated p-value representing the likelihood of the null hypothesis (AUC=0.5). A statistically derived value, based on the Youden index14, maximising the sum of the sensitivity and specificity was used to define the optimal cut-off value. A stepwise multivariate logistic regression was conducted to search for the independent predictors of a positive response. A criterion of p<0.05 for entry and p≥0.10 for removal was imposed in this procedure. All p-values were two-tailed. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, Version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

STUDY POPULATION AND BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

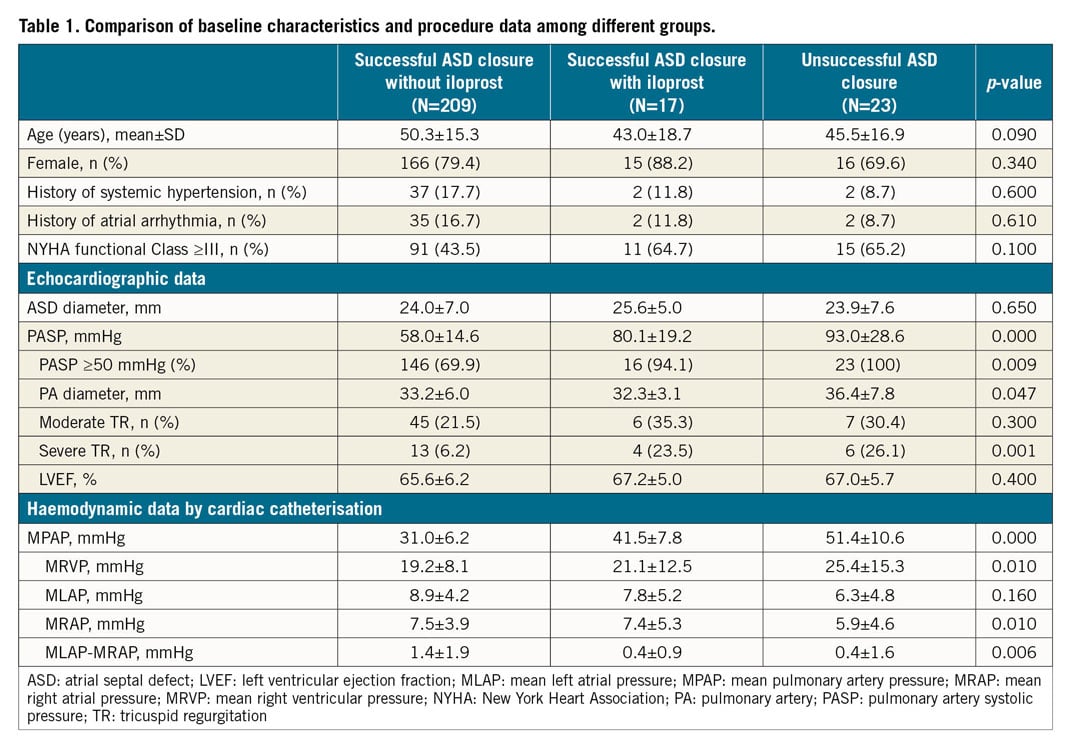

Of the 249 patients who underwent attempted transcatheter ASD closure, 209 had successful closure without PAH-specific medicine, 17 had successful closure only after administration of inhaled iloprost, and 23 were failures, even combined with inhaled iloprost. Table 1 shows the main clinical and procedure data. PASP by echocardiography was significantly lower in the successful closure without iloprost group compared to the successful closure with inhaled iloprost group and the unsuccessful closure group (58.0±14.6 mmHg vs 80.1±19.2 mmHg and 93.0±28.6 mmHg, respectively; both p<0.01). There were no differences in gender, age, history of systemic hypertension, history of atrial arrhythmia, NYHA functional Class ≥III, ASD diameter and LVEF (all p>0.05). The difference between mean left atrial pressure and mean right atrial pressure was higher in the successful ASD closure without iloprost group than in the successful closure with inhaled iloprost group and the unsuccessful closure group (1.4±1.9 mmHg vs 0.4±0.9 mmHg and 0.4±1.6 mmHg, respectively; both p<0.01). This indicates that the former group had more left-to-right shunts as compared with the latter two groups.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC FOLLOW-UP AFTER TRANSCATHETER CLOSURE

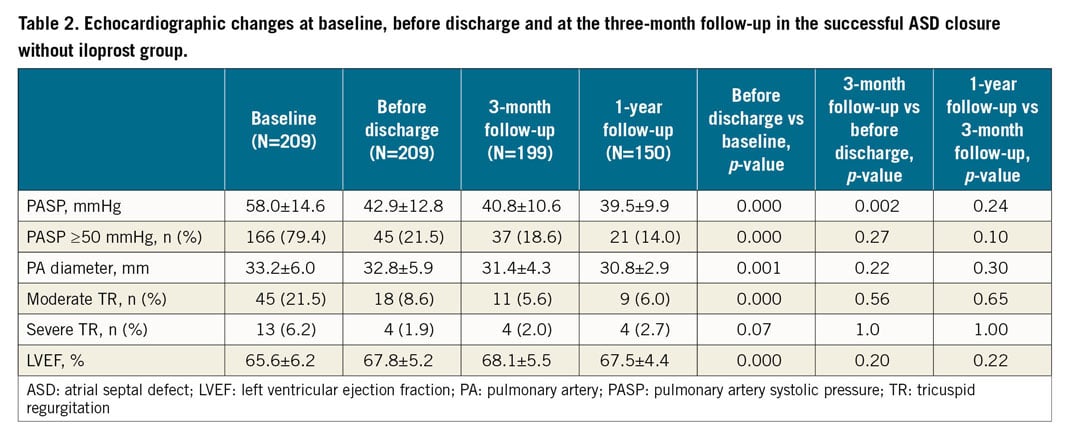

After discharge, 9.1% (19 cases) of patients who were successful-closure patients without inhaled iloprost and 76.4% (13 cases) of patients who were successful-closure patients with inhaled iloprost received oral PAH-specific medicine. None of the patients who were followed up died. Among the first group, PASP by echocardiography was significantly decreased before discharge compared with baseline (42.9±12.8 mmHg vs 58.0±14.6 mmHg; p<0.00; N=209). At the three-month (N=199) and one-year follow-up (N=170), the improvements were stable (before discharge, 42.9±12.8 mmHg; three-month follow-up, 40.8±10.6 mmHg; one-year follow-up, 39.5±9.9 mmHg; p>0.05). There was a dramatic decrease in the percentage of patients with PASP ≥50 mmHg from baseline to the one-year follow-up (79.4% to 14.0%, p<0.001). Before discharge, the LVEF was increased (65.6±6.2% vs 67.8±5.2%; p=0.001), and the pulmonary artery diameter (33.2±6.0 mm vs 32.8±5.9 mm, p<0.001) and percentage of moderate TR (21.5% vs 8.6%, p<0.001) were decreased compared with baseline. These three indices did not change significantly at the three-month and one-year follow-up (Table 2).

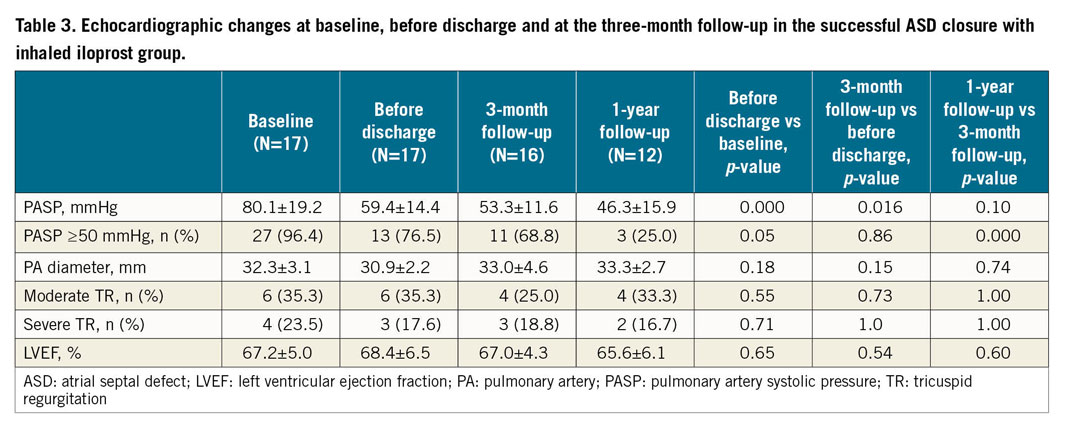

Among the 17 patients with inhaled iloprost in whom closure was successful, a decrease in PASP by echocardiography before discharge compared with baseline was observed (59.4±14.4 mmHg vs 80.1±19.2 mmHg; p<0.001; N=17). Continued improvements occurred at the three-month (53.3±11.6 mmHg, N=16) and one-year (46.3±15.9 mmHg, N=12) follow-up (both p<0.001 compared with discharge). There was a dramatic decrease in the percentage of patients with PASP ≥50 mmHg from baseline to the one-year follow-up (96.4% to 21.4%, p<0.001). The pulmonary artery diameter, LVEF and percentage of TR did not change (all p>0.05) (Table 3).

ROC CURVE ANALYSES OF MPAP BY CATHETERISATION

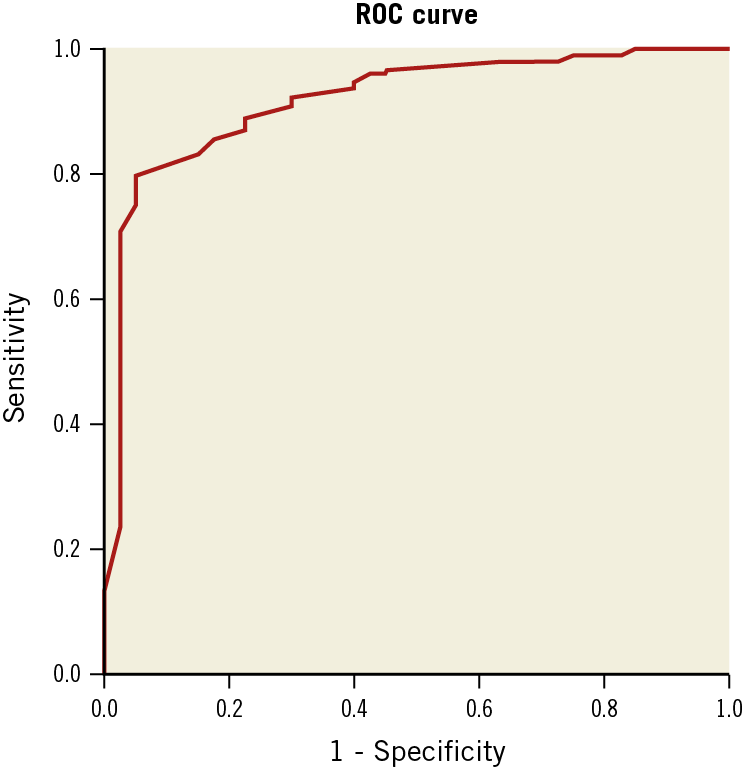

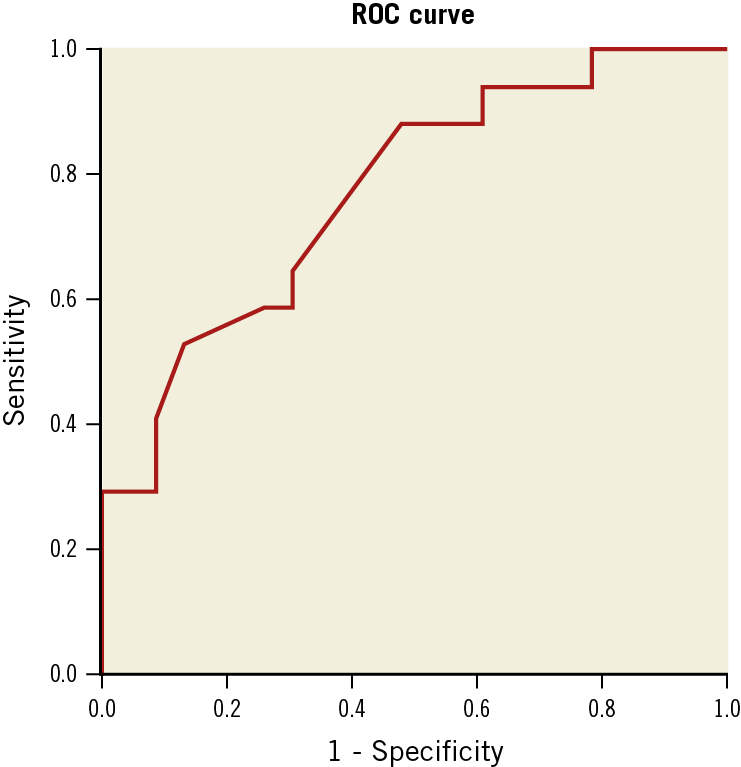

The ROC curve analyses were performed twice. First, we pooled all the patients into the analysis to determine the optimal cut-off value of MPAP by catheterisation in predicting a positive response without any PAH-specific medicine. The result of ROC curve analysis showed that the AUC of MPAP was 0.919 (CI: 0.873-0.966, p<0.001) (Figure 3). The optimal cut-off point of MPAP for predicting a positive response after attempting closure without any PAH-specific medicine was 35 mmHg. The sensitivity and specificity of this cut-off value were 79.9% and 95.0%, respectively. This means that 79.9% of patients with a positive response had MPAP ≤35 mmHg and 95.0% of patients with a negative response had MPAP >35 mmHg. Second, the ROC curve analysis was performed in patients who had received inhaled iloprost during the procedure to detect the optimal cut-off value of MPAP for predicting those who could not achieve a positive response, even when combined with PAH-specific medicine. The result of ROC curve analysis showed that the AUC was 0.774 (CI: 0.28-0.919) (Figure 4). The optimal cut-off point of MPAP for predicting a negative response after attempted ASD occlusion combined with inhaled iloprost was 50 mmHg. The sensitivity and specificity of this cut-off value were 88.2% and 52.2%, respectively. A total of 88.2% of patients with a positive response had MPAP <50 mmHg (but ≥35 mmHg) and 52.2% of patients with a negative response had MPAP ≥50 mmHg.

Figure 3. ROC curve for MPAP in predicting a positive response after attempted closure without inhaled PAH-specific medicine. MPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; ROC: receiver operating characteristic

Figure 4. ROC curve for MPAP in predicting a positive response after attempted closure with inhaled PAH-specific medicine. MPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; ROC: receiver operating characteristic

MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS

The independent variables included in the multivariate logistic regression are the variables shown in Table 1. If inhaled iloprost was not given, multivariate analysis found that only MPAP was an independent predictor of positive response (Exp[B]=0.811, p<0.001). If inhaled iloprost was given to patients when necessary, multivariate analysis found that only MPAP was an independent predictor of positive response (Exp[B]=0.807, p<0.001).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study included the largest series of ASD patients with PAH with an indication for closure. We confirmed the reliability of using our proposed indication (i.e., a positive response) for permanent closure in ASD patients with PAH. Most of the patients with a positive response undergoing permanent closure had a normal PASP at the one-year follow-up. We found that MPAP could be a simple but powerful index to predict a positive response and thus an indication for closure. Multivariate analysis found that only MPAP was an independent predictor of positive response. The optimal cut-off value of MPAP to predict a positive response without PAH-specific medicine was 35.0 mmHg, with a sensitivity of 79.9% and a specificity of 95.0%. Administration of inhaled iloprost extended the cut-off point to 50.0 mmHg to reach a positive response. The sensitivity and specificity of this cut-off value were 88.2% and 52.2%, respectively.

Although current guidelines recommend that ASD patients with pulmonary vascular resistance ≥5 Wood units (WU) but <2/3 systemic vascular resistance or pulmonary arterial pressure <2/3 systemic pressure (baseline or when challenged with vasodilators, preferably nitric oxide, or after targeted PAH therapy) and evidence of net left-to-right shunt (Qp:Qs >1.5) may be considered for intervention (class II B, level of evidence C), this recommendation is based on poor evidence9. The definitive indication for transcatheter closure of ASD with PAH remains controversial; previous studies either enrolled very few cases or are very old3,10,15,16.

Steele et al reported that all four surgically treated ASD patients with total pulmonary resistance greater than or equal to 15 U/m2 died, while, of the 22 surgically treated patients with total pulmonary resistance less than 15 U/m2, 19 remained alive with significant regression of symptoms3. Sánchez-Recalde et al found that patients with a positive response (defined as a ≥25% reduction in PASP after occlusion, relative to the baseline level) had a good prognosis after closure, but their study included only five patients10. Attie et al performed a large randomised controlled study and concluded that surgical closure was superior to medical treatment in patients >40 years old with secundum ASD. However, they did not analyse the effectiveness of surgical closure in PAH subgroups and presented no implication about the indication for transcatheter closure of ASD with PAH15. Huang et al reported transcatheter closure in seven ASD patients with PASP ≥60 mmHg and pulmonary vascular resistance ≥6 WU who had good short-term and medium-term outcomes16.

In China, test occlusion with a balloon prior to closure is not generally used. The occluding device used in this study has three layers of isolation membrane. The vast majority of the patients would have no or very trivial residual shunt after attempted occlusion, based on our clinical experience, as confirmed by intraoperative echocardiography. Additionally, if the patients were still to have a large shunt (>3 mm) by echocardiography, these patients would be excluded (N=15). Therefore, direct testing with an occluder device without a balloon test was equally informative. Because our centre is an adult heart centre, no children (<12 years) were included in the study. The mean age of this cohort was approximately 45 years. In this study, a positive response to attempted occlusion was defined as MPAP ≤30 mmHg or the decrement percentage of it ≥20% compared with baseline immediately after attempted occlusion, without a decrease in the aortic blood pressure or an increase in the ventricular end-diastolic pressure. We found that the PASP by echocardiography was significantly decreased before discharge and at the one-year follow-up. In previous studies, PASP measured by echocardiography ≥40 mmHg was regarded as PAH7,17. However, this criterion was thought to be incorrect, and PAH is regarded as PASP by echocardiography ≥50 mmHg in the current ESC guidelines13. We adopted this criterion in this study. In patients with successful closure without inhaled iloprost, just 14.0% of patients did not reach normalisation of PASP (<50 mmHg) at the one-year follow-up, while the percentage was 79.4% at baseline. In patients with successful closure with inhaled iloprost, only 21.4% of patients (96.4% at baseline) did not reach normalisation of PASP at the one-year follow-up. These results suggested that our proposed indication for permanent closure in ASD patients with PAH is reliable.

In the whole population, the optimal cut-off point of MPAP for predicting a positive response after attempted closure without any PAH-specific medicine was 35 mmHg. The AUC was 0.919. Seventy-nine point nine percent (79.9%) of patients with a positive response had MPAP ≤35 mmHg and 95.0% of patients with a negative response had MPAP >35 mmHg. In patients with a negative response after attempted occlusion, inhaled iloprost was then given, and MPAP was measured again. Administration of inhaled iloprost extended the cut-off point to 50.0 mmHg to reach a positive response. The sensitivity and specificity of this cut-off value were 88.2% and 52.2%, respectively. The high values of AUC, sensitivity and specificity in the above analyses supported our hypothesis that MPAP could be a simple but powerful index to predict a positive response and thus an indication for closure. Our results were consistent with the results reported by Yong et al, which showed that an independent predictor of normalisation of PASP after transcatheter ASD closure was a lower baseline pulmonary pressure17. A large randomised controlled study found that MPAP >35 mmHg was an important predictor of adverse outcomes, regardless of surgical closure or medical treatment15. The optimal cut-off point of MPAP for predicting a positive response without any PAH-specific medicine was coincidentally 35 mmHg.

Limitations

This study had several limitations which should be acknowledged. First, this was a single-centre retrospective analysis and quite a large proportion of patients (64/226) was lost at the one-year follow-up because the patients could not come back to our centre. This may have caused some bias in the analysis. However, the proportion of patients with complete three-month follow-up was high, and just 11 patients were lost. The conclusions of our study could also be drawn from this short-term (three months) follow-up. Some data, such as Qp/Qs, cardiac output, and pulmonary vascular resistance, were unavailable because these indices were not commonly collected in our clinical practice. However, we tried to simplify a hitherto more complex decision process regarding eligibility for ASD closure, beyond the traditional Qp/Qs and pulmonary resistance methods. Second, the length of follow-up was still short, and a longer follow-up is needed. Third, oral PAH-specific medicine was given for almost all the patients with successful ASD closure in the inhaled iloprost group. The analysis could be confounded by the effect of the medicine. However, the study still showed that transcatheter closure in these patients was reasonable, although oral PAH-specific medicine might be needed for them. Fourth, patients with a negative response, even after inhaling iloprost, did not undergo transcatheter closure. Whether this group was suitable for transcatheter closure is unknown. However, this group of patients was unlikely to have normalisation of PASP because the percentage without normalisation of PASP at one-year follow-up in patients with successful closure with inhaled iloprost was up to 21.4%. Last, the patients in the study had not used pulmonary vasodilator agents before attempted occlusion; the conclusion of the study may not be applied to patients pre-treated with such agents.

Conclusions

This large-scale study confirmed the reliability of our proposed indication for permanent closure in a large cohort of adult ASD patients with PAH. MPAP could be a simple but powerful index to predict benefit from closure in these patients. Large-scale prospective studies are needed to confirm the encouraging results of our study.

|

Impact on daily practice This study tested our proposed indication for closure and provided a simple index for predicting this indication in a large cohort of atrial septal defect (ASD) patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). |

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.