- percutaneous coronary intervention

- cardiogenic shock

- hospital mortality

- intra-aortic balloon pump

Abstract

Aims: The intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) is recommended by current guidelines as adjunct in patients with cardiogenic shock, despite the lack of larger clinical trials. We sought to investigate the use and impact on mortality of IABP in current practice of percutaneous coronary interventions in Europe.

Methods and results: Between May 2005 and April 2008 a total of 47,407 consecutive patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in 176 centres in 33 countries in Europe and the Mediterranean basin were enrolled into the registry. From these, 8,102 had ST-elevation myocardial infarction and 7,999 non-ST elevation myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock was observed in 7.9% and 2.1%, respectively. Of the 653 patients with cardiogenic shock 25% were treated with an IABP. In-hospital mortality, with and without IABP, was 56.9% and 36.1%. In the multivariate analysis the use of IABP was not associated with an improved survival (odds ratio 1.47; 95% CI 0.97-2.21, p=0.07).

Conclusions: In current clinical practice in Europe, IABP is used only in one quarter of patients with cardiogenic shock treated with primary PCI. However, there was no hint of a beneficial effect of IABP on outcome. Therefore, a large randomised clinical trial is urgently needed to define the role of IABP in patients with PCI for shock.

Introduction

Cardiogenic shock remains the major cause of death in patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction1. Early revascularisation therapy has been shown to improve the prognosis of these patients2. Despite the use of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) mortality in patients with shock is still around 40%-50%3. The intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was introduced in 1968 and improves systemic and coronary diastolic blood pressure and reduces afterload and myocardial work4. These effects are believed to improve myocardial recovery during ischaemia and reperfusion and ultimately reduce mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock. Current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines support the use of IABP (class 1c recommendation) in patients with cardiogenic shock5. A recent meta-analysis has questioned the value of IABP, especially in patients with primary PCI6. Therefore we sought to investigate the use of IABP in patients with PCI for cardiogenic shock in Europe.

Methods

EHS PCI-Registry

The PCI-Registry was conducted between May 2005 and April 2008 as the first continuous registry within the Euro Heart Survey Programme of the European Society of Cardiology. It was a prospective, multicentre, observational study to document current practice of PCI in consecutive patients in the real life setting throughout Europe, independent of the indication for PCI and to evaluate to which extent clinical practice endorses existing ESC practice guidelines in the different settings of PCI. Details of the Euro Heart Survey (EHS) PCI registry have been published in more detail7.

Patient enrolment

In brief, a total of 176 centres from 33 ESC member countries participated, including university hospitals, tertiary care centres as well as community hospitals. The centres were asked to continuously enrol consecutive patients scheduled for emergent, urgent or elective PCI, independent of age, gender, and any concomitant diseases and independent of the indication for PCI. Those patients who had already participated in (e.g., randomised) trials or other registries were also eligible for inclusion. If continuous consecutive enrolment was not feasible due to high yearly numbers of PCI, those centres were asked to recruit consecutive patients from day one to seven of every calendar month throughout the study period. The protocol of the PCI-Registry was approved by the ethical committees responsible for the participating centres, as required by local rules.

Data collection

Data was collected using online internet data capture. The electronic case report form was provided by the Euro Heart Survey Team at the European Heart House and was programmed on the basis of the European Cardiology Audit and Registration Data Standards (CARDS) for PCI. All patients gave informed consent for processing their anonymous data. Data was collected on patients’ characteristics, including age, gender, cardiovascular risk factors, concomitant diseases, prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, prior cardiovascular interventions and chronic medical treatment; on indication for PCI, procedural details, adjunctive medical treatment, periprocedural complications, hospital outcome, and the recommendations for long-term medical treatment following PCI. Final editing of the data as well as the statistical analyses was performed at the Institut fuer Herzinfarktforschung Ludwigshafen an der Universitaet Heidelberg (IHF), Germany.

Classification of patients

Patients were classified in groups 1) with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) within 24 hours including primary PCI, facilitated PCI and rescue PCI (STEMI), 2) patients stabilised after STEMI > 24 hours with or without prior fibrinolysis but without primary PCI (post STEMI); 3) patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), 4) patients with unstable angina pectoris and per definition without biomarkers for myocardial damage (UAP), and 5) patients with stable angina and / or documented myocardial ischaemia (elective PCI). For this analysis we used data of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Cardiogenic shock was diagnosed in patients with systolic blood pressure <90mmHg, heart rate >100bpm and clinical signs of organ hypoperfusion7.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were planned and performed, characterising the registry population and subsets of patients defined by use of IABP. Absolute numbers and percentages were computed to describe the patient population with respect to categorical variables and means with standard deviation for metrical variables. These values were calculated from the available cases. The distribution of binary variables was compared between the subgroups by Pearson Chi-square test, the distribution of metrical variables by Mann-Whitney test.

In addition to IABP, independent predictors of in-hospital mortality were analysed using multivariable logistic regression. Adjusted odds ratios with 95%-confidence intervals were calculated for the single variables and p-values from the Wald test statistic. For clinical reasons, age, gender, diabetes and impaired renal function were forced into the model, and other characteristics exhibiting a bivariate association with use of IABP with p<0.2 were included in a backward selection procedure: prior myocardial infarction (MI), resuscitation, left main PCI, triple vessel disease, number of treated segments, treatment with aspirin, treatment with Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, use of inotropes, and artificial ventilation. The computations were performed using the SAS system release 9.1 on a personal computer (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

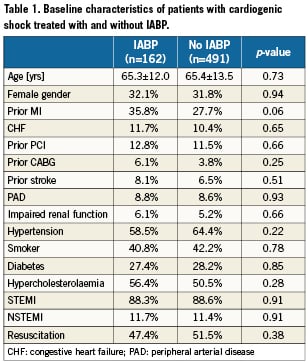

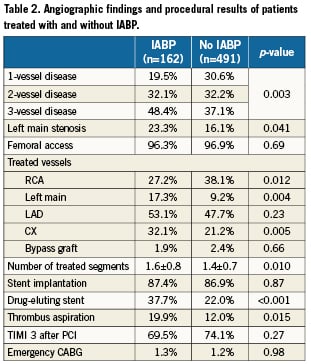

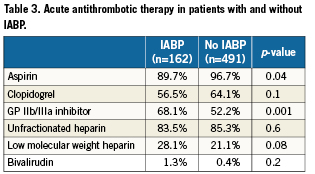

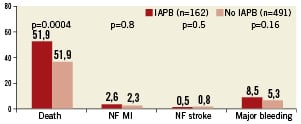

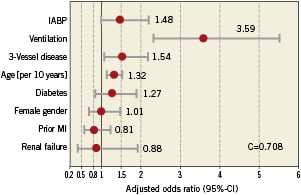

Between May 2005 and April 2008 a total of 47,407 consecutive patients undergoing PCI in 176 centres in 33 countries in Europe and the Mediterranean basin were enrolled into the registry. The information on use of IABP was documented for 42,317 patients. Of these 7,141 had STEMI and 5,315 NSTEMI and cardiogenic shock was observed in 578 (8.1%) and 75 (1.4%), respectively. Of the 653 patients with shock 24.8% were treated with IABP. The rate of shock patients treated with IABP was 25% both in patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. The baseline variables of patients treated with and without IABP are given in Table1. The angiographic features and procedural details of the patients are shown in Table2. A no/slow phenomenon was observed in 10.6% and 10.1% of the patients (p=0.9). Acute stent thrombosis within 48 hours were reported in 6.0% vs. 3.4% of the patients (p=0.17). The patients were treated with an intensive antithrombotic therapy (Table3). Inotropes were used in 72.9% of patients with and 65.0% of patients without IABP (p=0.08), respectively. Artificial ventilation was applied to 36.3% and 15.3%, (p<0.001) of the patients. The in-hospital events are shown in Figure 1. Renal failure requiring dialysis occurred in 10.3% vs. 5.6% (p=0.06) of the patients. Independent predictors of in-hospital mortality calculated in the multivariate analysis are shown in Figure2.

Figure 1. In-hospital events in patients treated with or without IABP. NF: non-fatal; MI: myocardial reinfarction

Figure 2. Multivariate analysis with predictors of in-hospital mortality.

Discussion

The results of our analysis do not suggest any beneficial effect of IABP on mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock treated with primary PCI. Despite the use of early revascularisation therapy mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock remains high4,8-11. Current guidelines recommend the use of IABP in patients with cardiogenic shock5. However, despite these recommendations the utilisation rate of IABP is low (15-40%)4,10,11. In our analysis, with data from a large cohort of shock patients from 33 European countries, the use of IABP was 25%. Interestingly there was no difference in the use of IABP between patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. These numbers certainly reflect some scepticism of the cardiologists against the use of IABP.

A recent meta-analysis of randomised trials and registries found contrasting results of the IABP in patients with STEMI complicated by cardiogenic shock6. In randomised trials the mortality tended to be lower with IABP in patients with fibrinolysis and without reperfusion therapy, while in registries the effect was significant. However, in registries the use IAPB was unfavourable in patients with primary PCI, while so far there is no randomised trial available with clinical endpoints evaluating IABP in primary PCI for cardiogenic shock. We did not observe an increase in stroke rate, however, there were some more bleeding complications with the use of IABP. In the meta-analysis an overall increase in major bleeding complications and stroke was observed with the use of the IABP6. In addition no benefit on left ventricular function was observed either.

Our findings and the findings of the meta-analysis hint into the same direction. The observation that IABP as adjunct to primary PCI does not improve outcome is somewhat unexpected. In theory IABP should increase myocardial perfusion and improve haemodynamics, which ultimately should decrease mortality12-14. In the randomised clinical trials using IABP as adjunct to primary PCI the mortality was low, both in patients with and without IABP, however IABP was used in STEMI but not in patients with cardiogenic shock13. However, the results of registries did not show any benefit of IABP in patients with primary PCI and shock either6,11,16. It might be argued that a selection bias cannot be excluded in the registries, which cannot be fully adjusted in the multivariate analysis. The sickest patients might be treated with IABP. In the catheterisation setting, it seems difficult to withhold patients from active therapy with IABP, even if their prognosis is extremely grim. In our analysis the patients with IABP needed more often mechanical ventilation, which was the one of the most important predictors of mortality. In addition more patients with IABP underwent left main PCI, which also was associated with an increased mortality in the multivariate analysis. However, our findings are supported by the results of a larger cohort of patients in the NRMI registry11. Here the use of IABP was associated even with an increased in mortality after primary PCI in cardiogenic shock (956/2035 vs. 401/955). The mortality difference remained significant even after adjustment for confounding factors. The reasons for this increase in mortality remain speculative. A systemic inflammation response to the device, as well the increase in bleeding complications due to local complications at the catheterisation insert site can be discussed15.

Another explanation might be longer ischaemic times in patients with IABP.

In a recently published small randomised pilot trial with surrogate endpoints no clinical benefit of the use of IABP in patients with primary PCI for AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock could be observed16. There was some effect of IABP on surrogate markers such as brain natriuretic peptide, but no advantage with respect to haemodynamic improvement or clinical outcome.

Taken all these results and observations together a large randomised clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness and safety of IABP in patients with cardiogenic shock undergoing primary PCI is eagerly needed. This trial (IABP-Shock II) has been recently started and will randomise over 600 patients with primary PCI for acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock17. The primary endpoint will be 30 day mortality. After the completion of this trial the definitive role of IABP as adjunct to PCI in shock can be defined.

Limitations

This was not a randomised clinical trial comparing IABP and conventional treatment in patients with cardiogenic shock. The definition of shock might have varied between the centres. Therefore, even after adjustment for confounding for baseline variables, we cannot rule out a selection bias which might have influenced the results. However, we did not observe any hint for a beneficial effect of IABP.

Conclusions

In current clinical practice in Europe IABP is used only in one quarter of patients with cardiogenic shock treated with primary PCI. However, there was no hint for a beneficial effect of IABP on mortality. Therefore a large randomised clinical trial is urgently needed to define the role of IABP in patients with PCI for shock.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.