Chronic heart failure (CHF) is associated with risk of volume overload due to progression of the underlying disease or as a result of patient-related causes such as poor compliance with water and salt restrictions, diuretics and other medication regimens. Decompensation episodes are clinically significant as they are related to increased mortality, readmission rates and patient discomfort, even though mortality seems to be decreasing slightly1. One focus for the treatment of acute heart failure is unloading of the heart. While often managed by increasing diuretics, some patients deteriorate and present with low cardiac output failure, which may progress into cardiogenic shock (CS).

While the definition of CS differs between studies and guidelines2, these patients are in grave danger of death and multiorgan failure and must be managed swiftly. While the existing data on diuretic regimens, use of inotropic agents, and level of haemodynamic monitoring are without clear evidence of benefit, and guidelines are relatively imprecise on how to manage these patients, most institutions have developed protocols to manage them with combinations of pharmacological or mechanical circulatory support, and many are improved and stabilised with treatment3.

Mechanical circulatory support may be considered to stabilise the patients in shock2. For more than four decades, the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was used for CS from many causes, including acute myocardial infarction, postoperative heart failure and decompensated CHF.

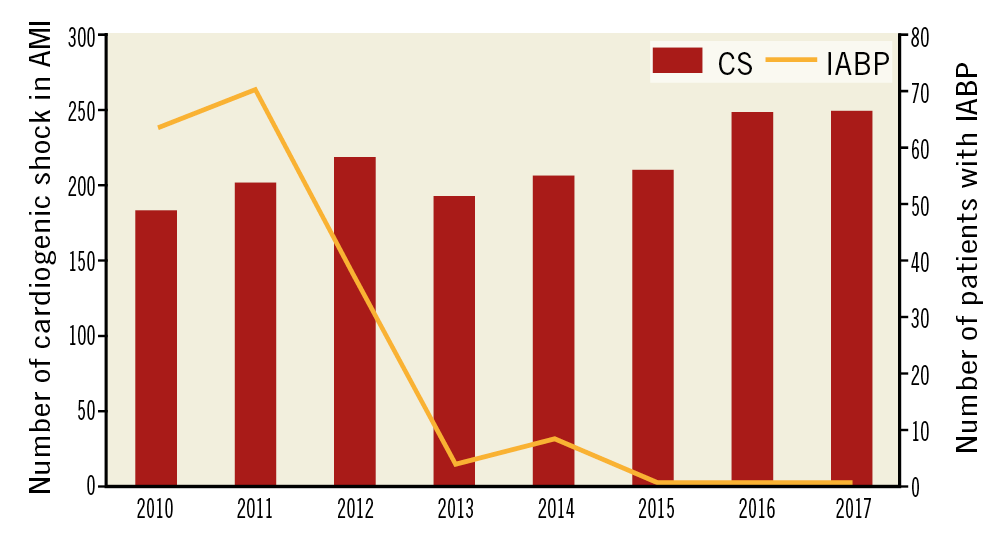

The efficacy of mechanical circulatory support devices has never been convincingly documented in large prospective randomised trials, with the exception of the IABP-SHOCK II trial by Thiele et al in 20124. This trial showed that, in patients with CS from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) undergoing acute percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the use of IABP had no effect on haemodynamics or mortality. Since then, the use of IABP for CS complicating AMI has been abandoned by many institutions5 (Figure 1), which is probably also the case outside the setting of AMI and shock. Other devices that may be applied in this setting include micro-axial pumps, such as the Impella® (Abiomed, Danvers, MA, USA), which is percutaneous and haemodynamically efficient6, but also remains unproven with regard to clinical efficacy. An ongoing large clinical trial is seeking to establish this in patients with AMI7.

Figure 1. Number of cardiogenic shock cases and use of IABP in two tertiary heart centres in Denmark 2010-2017, covering 3.9 million inhabitants. Data adapted from Helgestad et al, 20195.

Decompensated heart failure and cardiogenic shock

CS in the setting of decompensated CHF may differ from CS in relation to AMI in a number of respects. First, the decompensation occurs in a patient who has usually been stable on heart failure medications, including diuretics. Second, in CHF, the heart has remodelled to maintain stroke volume despite a low ejection fraction and the circulation may tolerate increased left atrial (LA) pressure better. Third, the degree of CS and secondary organ failure is often moderate. Fourth, volume overload is almost uniformly severe in CHF, whereas the AMI CS patient is usually euvolaemic.

This fits well with the population included in the trial by den Uil and colleagues reported in this issue of EuroIntervention –Primary intra-aortic balloon support versus inotropes for decompensated heart failure and low output: a randomised trial8.

The authors should be commended for careful selection for the trial of patients who had a failed primary management strategy of escalation of diuretics and volume restriction, and who had deteriorated by developing a state of pre-shock and CS, with low blood pressure, increased filling pressures and signs of low cardiac output and organ dysfunction with low SvO2 as the primary haemodynamic marker. A mean lactate level of 2.0 mmol/l and inclusion within 19-25 hours of hospitalisation suggested that patients were managed swiftly and not allowed to develop prolonged shock before inclusion in the trial.

In the trial, the use of IABP for 48 hours or more was associated with a significantly more favourable effect on several haemodynamic parameters than with a strategy based on inotropes alone (primarily low-dose enoximone): increasing SvO2 after 3 hours, and after 48 hours increasing cardiac power, decreasing NT-proBNP levels, and three times more negative fluid balance. The study was underpowered to show any differences in clinical outcomes, and patients treated with an IABP strategy had a significantly longer length of stay, which may in part be attributed to more frequent use of left ventricular assist devices and heart transplant in these patients.

The authors should be congratulated on performing the trial, not least for the rigorously described inclusion criteria, effectively identifying and randomising patients “sliding” on first-line management of decompensated heart failure.

The trial has several limitations. It was a single-centre trial, the intervention was open label and a significant number of patients had crossover within 48 hours of randomisation, numerically more patients in the IABP group were mechanically ventilated, the primary endpoint was already assessed after 3 hours, and no measures of cardiac output outside the cardiac power calculations are presented. Furthermore, by protocol, the control group received a very low dose of enoximone at the time (3 hours) of the primary endpoint measurement. Nevertheless, the results are intriguing, and could inspire others to perform more, preferably larger-scale trials in this patient population and preferably considering the addition of a strategy based on micro-axial pumps, where data on the efficacy outside of AMI are also sorely needed2.

For the time being, the trial in itself should not change heart failure management guidelines but may underline the need for differentiating the cause of CS and also probably for pursuing the development of management guidelines specifically for these causes of CS.

Conflict of interest statement

J.E. Møller has received a speaker’s fee and research grant from Abiomed. J.E. Møller and C. Hassager are investigators in the DanGer Shock trial. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.