Acute restoration of myocardial flow during primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is pivotal to the treatment of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, reperfusion injury and reduction of nutritional flow may occur despite successful re-opening and stent implantation in the infarct-related culprit lesion, and therefore an apparently normal epicardial flow may not reflect an adequate flow at the microvascular level. Thus, infarct extension may occur without visually observed flow reduction (no-reflow) or distal embolisation, and attempts to protect the peripheral vascular bed by thrombus aspiration or distal protection to avoid these complications have not been convincing.

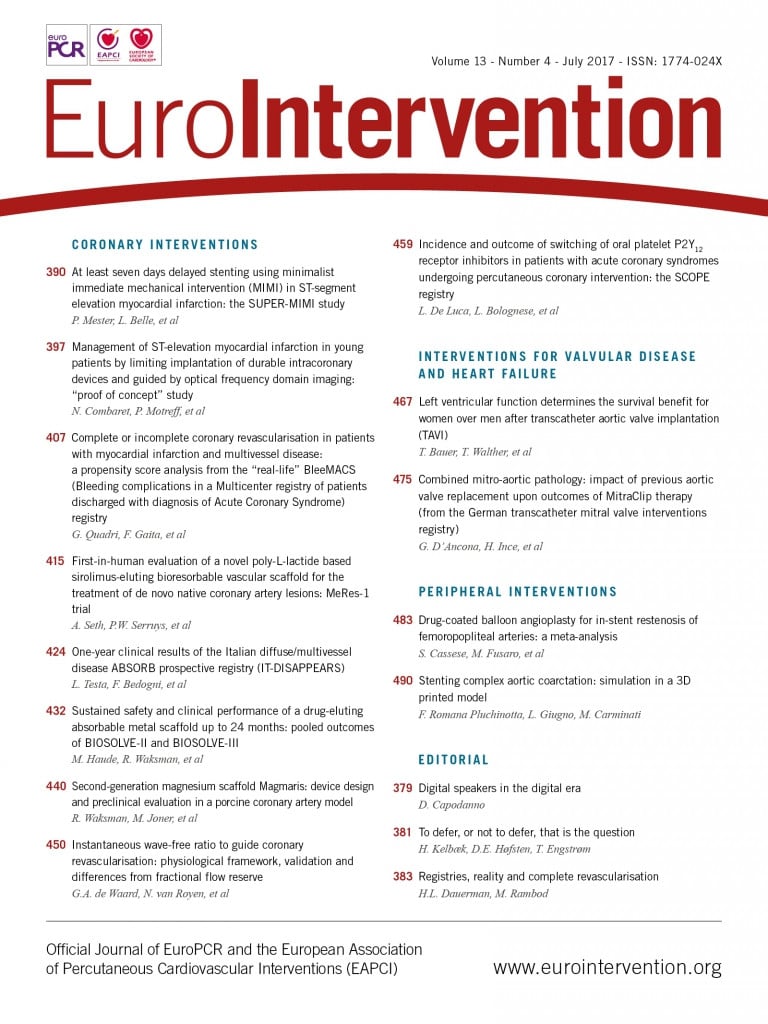

Sustained no-reflow is associated with the development of large myocardial infarcts and a high risk of ensuing heart failure. It occurs in a certain percentage of PCI procedures in the presence of a high thrombus or plaque burden and is induced by vasoactive substances in concert with increased platelet reactivity. Several observational reports have indicated that the risk of no-reflow and distal embolisation is diminished by deferring stent implantation, because both thrombus burden and microvascular disturbances are reduced with time after flow re-establishment. On the other hand, randomised trials have only been able to demonstrate benefit by stent deferral in certain surrogate endpoints (Table 1).

Notwithstanding previously published results from two French centres in favour of immediate stenting, the same centres have followed the defer concept with impressive dedication, and in this issue of EuroIntervention they focus on optimising STEMI intervention by deferring stent implantation two to 30 days after minimal manipulation of the culprit lesion to restore flow. In the Combaret et al study1, the authors implanted a bioresorbable scaffold guided by intravascular imaging a median of four days after the index procedure in a selected group of relatively young patients, and report one reinfarction as the only major cardiac event during six months of follow-up.

In the Mester et al study2, stent implantation was scheduled a median of seven days after the acute episode and, despite a considerable residual stenosis after the index PCI, the only adverse events reported were re-occlusion of the infarct-related artery in two patients not receiving glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Stent implantation could be waived in more than one third of these patients.

Albeit small and non-randomised, these two studies are valuable contributions to the ongoing attempt to improve invasive treatment of patients with STEMI. The concept of regaining the vasoactive and endothelial properties of the vessel by use of bioresorbable scaffolds is intriguing and can often be performed straight away, because the majority of STEMI vessels contain soft non-calcified plaque. On the other hand, care must be taken with regard to the sizing of the scaffold and in respect of the increased risk of scaffold thrombosis.

The limited number of patients in these two studies impedes any firm conclusion concerning the safety of the defer strategy, and the compilation of current experience –not least from our own DANAMI 3-DEFER trial– indicates that deferred stent implantation should not be routinely exercised in patients with STEMI3-6. However, the strategy seems safe in cases where a stable blood flow in the infarct-related artery can be restored by minimal manipulation with the supplement of efficient antithrombotic medication, and it cannot be ruled out that certain subgroups of patients with STEMI –especially those with long thrombotic lesions at the index procedure and those with non-significant lesions at the second procedure– may benefit from deferred stenting or even no stenting at all.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.