Voltaire (1694-1778)

Setting the stage

The concept of preparing the coronary lesion for mechanical intervention by providing antithrombotic therapy upfront - which acts by reducing thrombus burden and thereby limiting downstream thrombus embolisation to microcirculation - has been investigated across the whole spectrum of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) including patients with non-ST-elevation ACS (NSTEACS) as well as ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)1-4. The results generated by such multiple studies have been a matter of ongoing debate, and the concept of upstream therapy has never gained widespread acceptance in clinical practice. This may largely be due to the lack of properly powered studies for clinical endpoints in STEMI patients2,3, and the concerns for a disproportionate increase in bleeding hazard in NSTEACS4,5, a setting in which the longer duration of upstream therapy and advanced age, along with multiple comorbid conditions are much more prevalent.

This leaves the interventional cardiologist no choice but to face coronary thrombus burden by means of manual or mechanical thrombectomy, since even relatively potent antithrombotic agents show delay in action6,7, and/or require time before effective pharmacological thrombectomy can be successfully established. Yet, thrombectomy is an unproven treatment strategy in NSTEACS, and it frequently results in suboptimal thrombus removal in STEMI patients.

Coronary stenting is recommended with a Class 1A indication during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to reduce reocclusion and restenosis8. Yet, stent apposition squeezes the endoluminal component of the coronary plaque and dislodges the residual superimposed thrombus distally. Should we defer stenting largely thrombotic lesions once normal anterograde flow is observed or established after manual or mechanical thrombectomy? Can we even dare to refrain from stenting some largely thrombotic lesions with minimal lumen obstruction to allow for a spontaneous, perhaps more physiological lesion healing response? Is this safe? Is this more effective?

Historical perspective

The management of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has seen momentous changes in the last decades. The 70s was the decade of the coronary care unit9, while the 80s and 90s were the decades of thrombolysis10. The late 90s as well as this last decade have been the decades of interventional cardiology and mechanical revascularisation11, while the most recent years have seen the increasing popularity of approaches to refine primary percutaneous coronary intervention, such as transradial access and thrombectomy12,13. However, the concept of mechanically disrupting a coronary thrombosis actually dates back to 1979, when Rentrop and colleagues first reported on the use of a guidewire to dislodge an occluding intracoronary thrombus after selective thrombolysis14.

State of the art of treatment for acute myocardial infarction

The current management of suspected AMI is based on a comprehensive integration and optimisation of care. It begins with timely triage and administration of medications (e.g., aspirin, P2Y12 ADP receptor antagonists, or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors)8,15, and prompt transfer to a catheterisation laboratory for emergent coronary angiography. If coronary angiography confirms the presence of a significant coronary stenosis or occlusion, then the culprit vessel is wired. Thrombus burden and perfusion are assessed carefully, as even guidewire passage may be sufficient to gain reperfusion in several cases16. In many centres, thrombectomy, usually by means of manual suction devices, is then performed. Some operators do this when thrombus is evident or most likely, while others do this routinely, given the underlying hypothesis that some degree of platelet and fibrin deposition is always present in an acute coronary syndrome. Depending on the angiographic results after thrombectomy, balloon dilation followed by stenting or direct stenting is then typically performed, and the procedure is concluded unless there is a need for post-dilatation or additional intervention17.

Shifting the paradigm

The routine approach to the management of AMI outlined above has recently been challenged. First, the availability of safe and effective thrombectomy devices may leave the interventional cardiologists with a post-thrombectomy angiographic result which is largely satisfactory (i.e., without significant stenosis)18,19. What should the operator do in such cases? Should balloon angioplasty and/or stenting be carried out nonetheless, given that the all too unstable plaque might need sealing and stabilisation?

In other cases, the operator might feel that, even if thrombectomy or predilation do not completely normalise the angiographic outlook of the culprit vessel, stenting might best be deferred in order to give time for thrombus resolution and unplugging of the myocardial capillary bed20.

The present issue of EuroIntervention sheds new light on these important questions by publishing three important articles. First, Escaned and colleagues clarify the role of thrombectomy without additional angioplasty or stenting as an adequate treatment for STEMI in carefully selected cases21. They summarise data stemming from a total of 1,737 consecutive patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention, 757 (44%) of whom underwent thrombectomy and 28 (1.6%) of the total who had thrombectomy only. This case series, exploiting control angiography in 11 patients, confirms and extends previous reports on this interesting management strategy18,19. The great value of this report is to bring the concept of a tailored mechanical approach in patients with STEMI to the attention of the interventional cardiology community. As not all STEMI are alike, it is likely that a uniform therapeutic approach consisting of coronary stenting in this complex and multifactorial disease may not necessarily always be appropriate. Importantly, acute or subacute vessel reocclusion did not occur in this relatively small and highly selected series of STEMI patients. Yet, the 95% confidence interval of this unfavourable adverse event rate entails the possibility that this may still be observed in up to 9% of the cases, highlighting the need for much broader datasets to better inform clinical practice. Many issues remain at present unanswered, such as what is the role of concomitant antithrombotic regimen? It should be emphasised that the vast majority of patients in this series received concomitant glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition. Is this therapeutic target necessary to prevent early vessel reocclusion? As many of these cases appear to be related to a hypercoagulation stage, what is the role of direct or indirect thrombin inhibitors in preventing early as well as late ischaemic recurrences in this selected patient population? It is clear that more work needs to be done in this setting.

Kelbæk et al provide evidence from a prospective observational study, including 124 patients with STEMI, that deferred stenting after successful thrombectomy (±angioplasty with a 1.5-2.0 mm balloon) was feasible and safe in 91% of cases22. Notably, as many as 38% of patients in whom a deferred strategy was chosen did not require stenting at all 48 to 72 hours after the index procedure.

It is worrisome to note that in one patient in this series acute occlusion reoccurred despite bivalirudin infusion. In the authors’ own words, “it remains to be evaluated whether the risk of reocclusion in the period between the index and deferred procedure in addition to potential complications related to an additional invasive procedure including bleeding at the access site(s), is outweighed by a lower risk of embolisation and flow disturbances of the peripheral vascular bed of the infarct-related artery with subsequent impairment of left ventricular function and ensuing development of heart failure.”

Finally, Freixa and colleagues summarise the available evidence on deferred stenting for acute myocardial infarction pooling data from five non-randomised studies and one randomised trial, encompassing a total of 590 patients23. While they do not suggest that deferred stenting is clearly associated with midterm or long-term clinical benefits, they make the case that avoiding immediate stenting across the whole ACS spectrum might lead to fewer periprocedural complications (including a lower rate of reinfarctions in NSTEACS patients). Yet, it is important to emphasise that current evidence supporting deferred stenting in ACS is weak, and pooling data together does not necessarily make it stronger or more convincing.

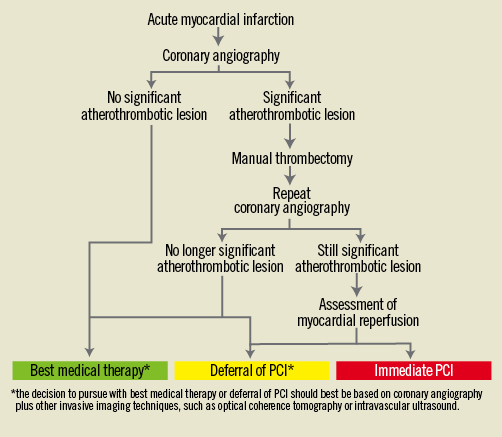

Given the importance of the topic and the novelty of the approaches covered in these three articles, they are all recommended reading and they could already be implemented in carefully selected settings and within a formal protocol (Figure 1), given their purported benefits (Table 1). However, some caveats persist, as in all early stage phases of technological or technical developments.

Figure 1. Paradigmatic algorithm for the invasive management of acute myocardial infarction.

First, only large-scale randomised trials will be able to define clearly the risk-benefit and cost-benefit balance of thrombectomy only or deferred stenting strategies for AMI. The first-generation randomised controlled studies on this topic are currently on-going and will generate more robust evidence allowing for a better assessment of the benefit to risk ratio of this attractive new therapeutic strategy.

Second, even if the safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of these novel strategies could be proven, medico-legal and malpractice issues should not be overlooked, as stenting is nowadays considered by many a panacea, thanks at least in part to the remarkable safety profile of current-generation devices. Third, a thrombectomy only or a deferred stenting strategy relying on angiography alone for decision making appears, in our opinion, ill-advised.

At this early stage, in-depth understanding of which patient population may derive the greatest benefit, or being able to identify risk markers for vessel reocclusion may require the use of invasive imaging modalities alone, or even in combination with functional macro or micro-circulation assessment.

Conclusions

While the management of acute myocardial infarction has been one of the greatest successes of interventional cardiology, there is still room for improvement. Strategies based on thrombectomy alone or deferred stenting might offer important clinical benefits to selected patients, and are clearly worth careful consideration in both clinical practice and research agenda.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.