Abstract

Aims: Considerable interest has been focused in recent years on the role of distal embolisation as a major determinant of impaired reperfusion after primary angioplasty for STEMI. The aim of the current study was to evaluate in a large cohort of STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty with glycoprotein (Gp) IIb-IIIa inhibitors, whether the impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion and survival may depend on time-to-treatment.

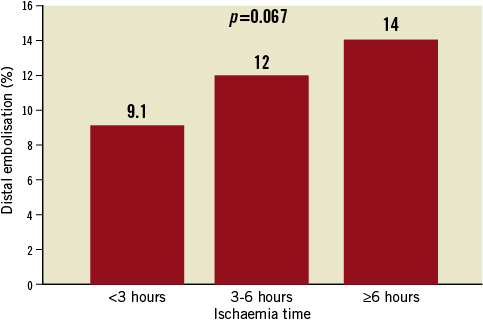

Methods and results: Our population is represented by 1,182 patients undergoing primary angioplasty for STEMI included in the EGYPT database. Patients were grouped according to time-to-treatment (<3 hours, 3-6 hours, >6 hours). Distal embolisation was defined as an abrupt “cutoff” in the main vessel or one of the coronary branches of the infarct-related artery, distal to the angioplasty site. Myocardial perfusion was evaluated by angiography or ST-segment resolution, whereas infarct size was estimated by using peak creatine kinase (CK) and CK-MB. Follow-up data were collected between 30 days and one year after primary angioplasty. Distal embolisation was observed in 132 patients (11.1%) and tended to occur more frequently in late presenters (p=0.067). Patients with distal embolisation less often had post-procedural Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 3 flow (p<0.001), post-procedural myocardial blush grade (MBG) 2-3 (p<0.001), complete ST-segment resolution (p=0.021) and larger infarct size (p=0.012). Distal embolisation was associated with a significantly higher mortality (9.2% vs. 2.7%, heart rate [HR] [95% CI]=3.41 [1.73-6.71], p<0.0001). The impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion and survival persisted for all time intervals.

Conclusions: This study showed that among STEMI patients treated with Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, the negative impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion and mortality is independent of the time from symptom onset to balloon angioplasty.

Introduction

Primary angioplasty as compared to thrombolysis has been shown to improve survival mainly due to a large percentage of restoration of TIMI 3 flow1,2. However, epicardial recanalisation does not guarantee optimal myocardial perfusion, which remains suboptimal in a relatively large proportion of patients3,4. In recent years, increased interest has been focused on the role of distal embolisation as a major determinant of impaired reperfusion5-7. However, few data have been reported concerning patients treated with Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, which may potentially minimise the occurrence and the prognostic impact of distal embolisation8-11. A recent study has suggested a time-related dependence on the prognostic impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion and infarct size12. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to evaluate, in a large cohort of STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty with Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, whether the impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion and survival depend on time-to-treatment.

Materials and methods

Our population is represented by a total of 1,182 patients with STEMI treated by primary angioplasty between 1998 and 2005, included in the EGYPT database13. All patients were admitted within 12 hours of symptom onset. All patients received aspirin (500 mg, intravenously) and heparin (10,000 IU, intravenously) as well as Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, but not clopidogrel, before the procedure, and were on double oral antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) for at least four weeks after stent implantation. Thereafter, aspirin or clopidogrel (in case of aspirin side-effects) were continued as monotherapy.

Angiograms and electrocardiograms (ECG) were not analysed by a central corelab, but data were provided by each principal investigator. Analysis of angiograms was based on standard definitions13. Angiographic myocardial perfusion was evaluated by myocardial blush grade (MBG14) or myocardial perfusion grade (MPG15). Distal embolisation was defined as an abrupt “cut-off” in the main vessel or one of the coronary branches of the infarct-related artery, distal to the angioplasty site5. Even though ST-segment analysis was performed according to the pre-specified criteria of each trial, data were provided according to uniform thresholds (<30%: no resolution; 30%-70%: partial resolution; >70%: complete resolution). Infarct size was estimated by using peak CK and CK-MB. Time from symptom onset to treatment was defined as the time from symptom onset to balloon inflation.

Clinical outcome

Clinical outcome was assessed between 30 days and one year after primary angioplasty by medical visit or alternatively, when not possible, by telephone contact.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS 15.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data were expressed as mean±SD and categorical data as percentage. The ANOVA test was appropriately used for continuous variables. The chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. In order to evaluate the impact of distal embolisation on angiographic and clinical outcome according to time-to-treatment, patients were divided in three groups as follows: <3 hours, 3-6 hours, >6 hours. The difference in event rates between groups during the follow-up period was assessed by the Kaplan-Meier method using the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was used to evaluate the impact of distal embolisation on survival after adjustment for significant (p<0.1) confounding baseline characteristics.

Results

Data on distal embolisation were available in a total of 1,182 patients. Distal embolisation was observed in 132 patients (11.1%). As shown in Figure 1, distal embolisation tended to occur more frequently in late presenters (p=0.067). Demographic, clinical, and angiographic characteristics according to distal embolisation and time-to-treatment are reported in Table 1. Patients with distal embolisation were older (p<0.001), with a larger prevalence of diabetes (p=0.01), previous myocardial infarction (MI) (p=0.048), advanced Killip class at presentation (p=0.018), abciximab administration (p<0.001), with a lower prevalence of smoking (p=0.04). These data were almost confirmed for all time intervals.

Figure 1. Occurrence of distal embolisation according to ischaemia time.

POST-PROCEDURAL TIMI FLOW AND MYOCARDIAL PERFUSION

As shown in Figure 2, distal embolisation was less often associated with post-procedural TIMI 3 flow and post-procedural MBG 2-3 (data available in 1,057 patients) across all time intervals.

Figure 2. Impact of distal embolisation on post-procedural TIMI 3 flow, MBG 2-3, complete ST-segment resolution, and CK-MB according to time-to-treatment.

ST-SEGMENT RESOLUTION

As shown in Figure 2, distal embolisation had a significant impact on complete ST-segment resolution (data available in 1,033 patients) only in the first three hours, whereas a minor effect (between three and six hours) or no effect (after six hours) was observed in later presenters.

INFARCT SIZE

As shown in Figure 2, distal embolisation had a statistically significant impact on infarct size (data available in 763 patients) in patients treated within the first three hours and between three to six hours. A similar impact was observed in late presenters (>6 hours), however it did not reach statistical significance.

MORTALITY

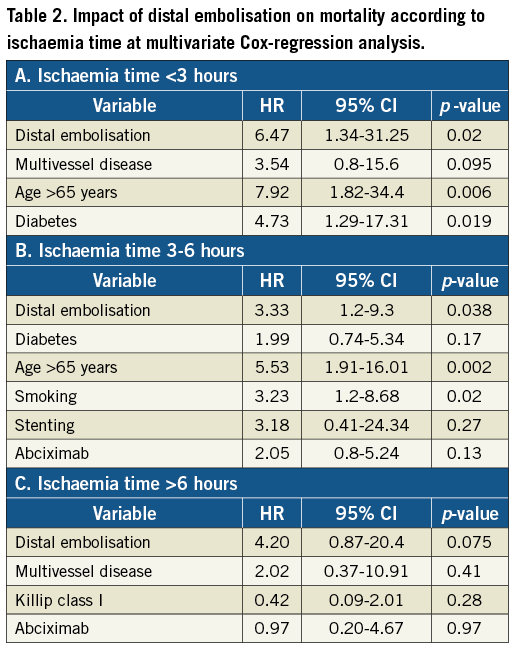

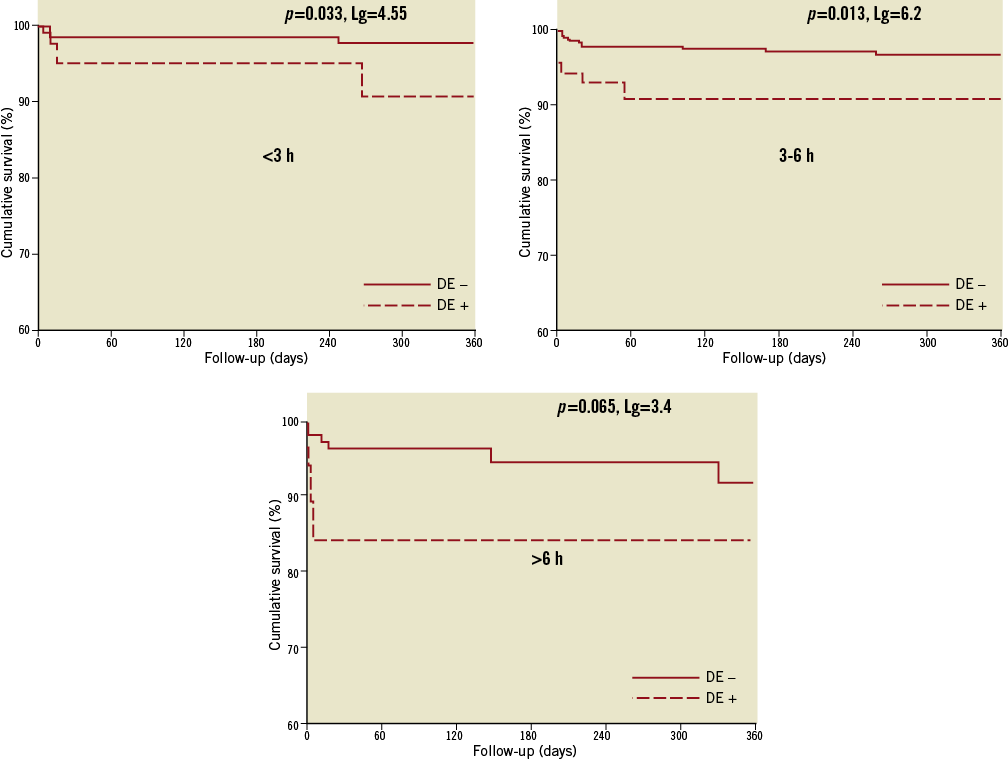

At 208±160 days follow-up, distal embolisation was associated with a significantly higher mortality (9.2% vs. 2.7%, HR [95% CI]=3.41 [1.73-6.71], p<0.0001). As shown in Figure 3, the impact of distal embolisation on survival was observed for patients treated within six hours from symptom onset, whereas a statistically weaker (even though clinically similar) impact in patients treated after the first six hours. These results were confirmed after correction for baseline confounding factors (Table 2).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival curves show a significant impact of distal embolisation on survival according to time-to-treatment.

Discussion

This is the first large study evaluating the impact of time-to-treatment on the role of distal embolisation in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors. We found that the occurrence of distal embolisation increased with longer ischaemia time. The impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion and mortality was not affected by time-to-treatment, as the deleterious effects of distal embolisation persisted even after six hours from symptom onset to treatment.

Several experimental studies have shown the implications of distal embolisation as a major determinant of infarct size and poor reperfusion after primary angioplasty. Sakuma et al6 have shown that the presence of distal embolisation is associated with an increase in the perfusion defect and final infarct size by 139% and 70%, respectively, as compared to the control group. Several reports in humans have shown that distal embolisation is a relatively common phenomenon in primary angioplasty. Based on a histological 3D reconstruction of the retrieved emboli, Limbruno et al16 observed that the embolic load was >2 mm3 in 15% of patients and >6 mm3 in 5% of patients, which could be detectable by angiography. Yip et al17 observed in 794 patients undergoing primary angioplasty that the incidence of no-reflow was significantly higher in patients with a high thrombus burden. It was observed in a recent report, by the use of intravascular ultrasound, that plaque volume reduction (an indirect sign of distal embolisation when excluding distal or proximal plaque shifting) was nine times higher in patients with post-procedural Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) perfusion grade 0-2, as compared to TIMI perfusion grade 318. Based on the histological analysis of retrieved debris, the Enhanced Myocardial Efficacy and Recovery by Aspiration of Liberated Debris (EMERALD) trial19 showed visible debris in 78% of patients. Henriques et al5 reported that the incidence of angiographically-detectable distal embolisation was 16%, and this was associated with poor reperfusion, larger infarct size and unfavourable five-year survival, as compared to patients without angiographic signs of distal embolisation.

However, due to the relationship between ischaemia duration, the amount of viable myocardium and myocardial perfusion20-22, which is larger in the first few hours from symptom onset, a time-dependence of the impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion and mortality would be expected. This issue was investigated by Napodano et al in a relatively small cohort of patients (n=40012). They found a similar impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion (as evaluated by MBG) between the first three hours and three to six hours from symptom onset, whereas no significant impact was observed after six hours. These data were not confirmed for ST-segment resolution, with paradoxically worse reperfusion in patients without distal embolisation within the first three hours from symptom onset as compared to patients with distal embolisation.

In our study, including a larger number of patients and all treated with Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, we found a larger occurrence of distal embolisation in late presenters. This may be explained by the difference in thrombus composition with longer ischaemia time. In fact, it has been shown that thrombus have larger platelet composition within the first hours, whereas fibrin is more represented with longer ischaemia time23. Therefore, in a population treated with Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, patients may be expected to have less distal embolisation within the first hours of symptom onset, as observed in our study.

The impact of distal embolisation on myocardial perfusion, infarct size and survival was not affected by the time of treatment. In fact, a similar impact was observed between <3 and three to six hours, whereas a less statistically significant impact was observed in late presenters, which may be due to the smaller population and therefore lower statistical power, as compared to early presenters. Remarkably, distal embolisation had a similar impact on myocardial blush but not on ST-segment resolution, which was mostly affected in patients treated within the first three hours from symptom onset. In fact, some discrepancies have been described between ST-segment resolution and myocardial blush in the evaluation of myocardial perfusion, since they evaluate two different phenomena24,25.

Several studies26,27 and a meta-analysis28 have shown that adjunctive thrombectomy reduces distal embolisation and improves myocardial perfusion. Recent data from the TAPAS trial have shown that routine use of manual thrombus aspiration is associated with a significant improvement in one-year survival29. Subgroup analyses showed that the benefits in terms of myocardial perfusion from adjunctive thrombectomy were not affected by the time delay, as they persisted in patients treated after three hours from symptom onset.

The benefits in survival have been confirmed in a recent meta-analysis on manual thrombectomy devices30.

Thus, due to the still relatively large incidence of distal embolisation observed in the current study, despite extensive use of Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, thrombectomy devices may be considered to prevent distal embolisation, improving myocardial perfusion and survival independently from the time of symptom onset.

Limitations

The major limitation of the current study is that it is a post hoc, non pre-specified analysis. Another limitation is the absence of a centralised corelab, even though angiographic and ECG data were mostly based on investigator evaluations with similar criteria across trials, except for angiographic myocardial perfusion, which was evaluated by MPG in two trials31,32. Enzymatic infarct size was estimated by peak CK and CK-MB, whereas the use of scintigraphic techniques or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which would have additionally provided data on microvascular obstruction, would have certainly improved the results. In addition, complete data on myocardial blush, ST-segment resolution and infarct size were not available for all patients. This study was based on an analysis performed in three subgroups of patients defined according to ischaemia time. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with the limitation related to the reduced statistical power in three subgroups when compared to the analysis performed in the overall population. We analysed overall mortality. However, at short-term follow-up after STEMI, mortality would be expected to be mostly cardiac-related. We used a fixed dose of heparin, whereas current guidelines suggest a weighted, adjusted dosage. Furthermore, activated clotting time (ACT) was not routinely checked. Data on clopidogrel loading dose were not available. However, this might play a minor issue in patients treated with strong antiplatelet drugs such as Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors. In addition, the therapy was prescribed for only four weeks, based on the recommendation available at that time. We observed a larger use of abciximab in patients with distal embolisation and whether this is or is not a drug effect cannot be addressed by our study. Furthermore, the evidence of beneficial effects from thrombectomy has only recently emerged30. Therefore, these devices were not used in our study, with a potential higher risk of distal embolisation. Patients were enrolled in current randomised trials and therefore have for the most part been highly selected. Furthermore, heterogeneity among trials included in this study cannot be excluded, due to the patients and the different follow-up lengths (ranging between 30 days in some trials, or up to six or 12 months in others). Therefore, caution should be exercised in extending the conclusion of this meta-analysis to the vast majority of STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty.

Conclusions

This study showed among STEMI patients treated with Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, that distal embolisation is associated with impaired myocardial perfusion and survival. These effects were not affected by time of treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.