Not long ago, thrombotic lesions were considered an off-label indication for drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation. As a matter of fact, seminal registries on the use of first-generation DES showed an increased risk of stent thrombosis in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome on admission1. This risk was even higher if the patient discontinued the dual antiplatelet therapy early after stent placement in the setting of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). In this regard, in the PREMIER registry, patients who had stopped thienopyridine therapy by 30 days after STEMI were more likely to die during the next 11 months (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 9.0, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.3 to 60.6)2. Similarly, the multinational GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) registry demonstrated an increased mortality in patients with STEMI receiving DES from six months to two years (HR 4.90, p=0.01)3. A more delayed healing of culprit plaques from STEMI patients as compared to those from stable coronary artery disease was evidenced in histopathological studies4. Besides, late acquired stent malapposition and hypersensitivity reaction to the polymeric coating of the DES were advocated as triggers for stent thrombosis in the context of STEMI5,6. The only benefit observed with this first-generation DES as compared to bare metal stents (BMS) was a reduction in target lesion revascularisation induced by a profound inhibition of neointimal proliferation7.

Technical improvements in stent designs made second-generation DES safer and more efficacious than both first-generation DES and BMS8,9. After the completion of dedicated randomised controlled trials10, revascularisation guidelines granted second-generation DES a class I, level of evidence A, over BMS in the context of STEMI11. New DES reduced the rate not only of repeat revascularisation but also of hard clinical events such as repeat myocardial infarction and even mortality10-12.

The MASTER study13 evaluated the performance of a biodegradable polymer-based sirolimus-eluting stent, Ultimaster®, versus its bare metal counterpart the Kaname® stent (both Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan) in patients receiving primary percutaneous intervention for STEMI.

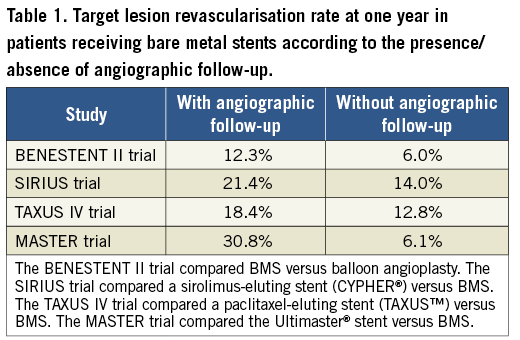

The study (n=500) was powered for the angiographic endpoint of late luminal loss (LLL) at six months. The clinical endpoint of target vessel failure was also evaluated at one-year follow-up. Overall, the study showed superiority of the DES over BMS in terms of LLL (mean value 0.09 mm vs. 0.79 mm, respectively; p=0.01). In addition, target vessel failure was also reduced at the expense of a reduction in target vessel revascularisation in the DES arm. The other components of the primary clinical endpoint occurred at a similar rate between groups. This study corroborates the capacity of the Ultimaster stent to inhibit neointimal proliferation which can be translated into a reduction in repeat revascularisation as compared to BMS. No other clinical inferences can be drawn from these results as the study was not powered for hard endpoints. The results of this trial are, however, hampered by the fact that benefit in repeat revascularisation was mainly observed in patients with angiographic follow-up (target lesion revascularisation 3.9% vs. 30.8%, DES vs. BMS, respectively) (Supplementary Table 4, reference 13). Furthermore, most of the repeat revascularisations occurred at the time of or early after the follow-up angiography (Figure 3, reference 13). Conversely, in patients without angiographic follow-up, target lesion revascularisation was no longer significantly different between groups (2.4% vs. 6.1%). This well-recognised phenomenon was first observed in the BENESTENT II trial and coined oculostenotic reflex14. The influence of the angiographic follow-up on target lesion revascularisation from several pivotal trials is presented in Table 1. In the MASTER trial13, the observation of a stent with evident neointimal proliferation could lead the investigators to use invasive or non-invasive tests to rule out ischaemia (data not reported). As a result, the rate of clinically driven repeat revascularisation was five times higher than in patients without angiographic follow-up. Therefore, to define the performance of a new stent, studies powered for clinical endpoints are needed to avoid the interference of the oculostenotic reflex15.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.