Abstract

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation is a relatively new technique to treat elderly and high-risk patients with aortic stenosis using a retrograde transfemoral, transsubclavian, transaortic or an antegrade transapical approach. TAVI procedures can be divided into two parts: the access to the cardiovascular system, and valve positioning and implantation. Regarding access, an antegrade transapical approach is intuitively easy to perform and thus the logical approach. At present a lateral mini-thoracotomy is required, but for the future percutaneous access and closure systems will be available. The transapical approach per se offers plenty of advantages as it is easy to perform, is very close to the target, antegrade, allows for easy guidewire insertion together with simple antegrade valve placement and a very controlled implantation. Despite this, in clinical reality many sites use a “transfemoral first” approach to TAVI, which is based merely on the belief that this is supposed to be less invasive; however, this belief is not substantiated by evidence-based data. In effect, the transapical approach offers the lowest access-related complication rates, and should therefore be the access of choice for many patients.

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has evolved as the standard therapeutic option for high-risk elderly patients with aortic stenosis (AS). TAVI can be accomplished using a retrograde transfemoral (TF), a retrograde transsubclavian (TSc), a retrograde transaortic (TAo) or an antegrade transapical (TA) approach.

The two most frequently used TAVI approaches, retrograde TF and antegrade TA, have seen a steep increase in patient numbers in the second half of the last decade: from 2005 until 2007 several feasibility trials were performed which led to CE approval for TF Medtronic CoreValve™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) as well as TF and TA Edwards SAPIEN™ (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) valve implantation in 20081-4. Since then, there has been a further tremendous increase in patient numbers, culminating in more than 50,000 patients treated with each of these devices to date.

Despite the lack of any evidence-based data a “TF first” approach is being used in many centres. This “TF first” approach may be based upon common sense that a TF percutaneous access may be less invasive than a TA access using a lateral mini-thoracotomy. There is, however, no randomised clinical trial comparing the two techniques. We believe that a broader view concerning elderly and high-risk patients with AS, bearing in mind important outcome parameters such as mortality and morbidity (stroke, vascular diseases, etc.), would be more appropriate. At present, the TA technique per se carries the lowest access-related complication rate, which is less than one percent5. Most importantly, Heart Team consultation and a joint decision about the best approach for the individual patient, keeping longer-term outcomes in mind, are warranted.

In this review we will focus on different aspects of the transapical approach –its technical aspects as well as the development of the techniques over the past years, literature results on the TA technique, comparability of the different results, the beauty of the TA approach, techniques to enable standardised TA access and closure, and perspectives such as the percutaneous TA technique.

Transapical (TA) approach: technique and accomplishments

TAVI per se can be separated into two parts: the first part is gaining access to the cardiovascular system to place a guidewire and a sheath, thus enabling valve insertion and placement at the target, the aortic annulus. The second part consists of exact positioning of the valve together with precise on-target implantation by means of balloon inflation or stepwise unsheathing.

The TA technique was experimentally evaluated in November and December 20046. First-in-human implantations performed in Leipzig in December 2004 and in Frankfurt in January 2005 were unsuccessful at that time due to lack of an oversizing technique7. With improved knowledge about sizing and oversizing in parallel with the availability of a 26 mm valve the first successful TA implantations were performed in Vancouver in the autumn of 20058 and in Leipzig in February 20069,4.

Technically, the TA approach is based on straightforward surgical thinking: keep the procedure simple and safe. Access was easily accomplished via an anterolateral mini-thoracotomy in the fifth or sixth intercostal space in the left midclavicular line. Pericardiotomy and stay sutures usually lead to optimal exposure of the left ventricular apex and some muscular tissue which is located slightly anterior10,11.

The antegrade TA access is then usually secured by two pledget reinforced purse-string stitches or alternatively by pledget reinforced U-stitches. In the rare case of frail tissue, temporary unloading of the ventricle, by moderate rapid ventricular pacing or rarely by femoral cardiopulmonary bypass, can be used. Overall, the TA approach is relatively easy and safe: TA puncture, antegrade wire placement, sheath and valve positioning as well as valve implantation, followed by retrieval of the access systems, are usually very straightforward, as described previously10,11. After standard closure of the incision, patients can usually be extubated directly. When using a standardised approach, the TA technique will be less invasive and as fast as the TF or other techniques would be. Many of the factors contributing to adverse outcomes originate from individual patients’ risk factors as well as some procedure-related causes.

There are several specific strengths of the antegrade TA technique. Many parts of the procedure, such as guidewire, sheath, valve insertion and placement, are much easier from the antegrade approach. Exact coaxial alignment can easily be accomplished using this technique, especially when using the Amplatz Super Stiff™ guidewire (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) to position the valve in an exactly coaxial orientation in relation to the aortic annulus10.

Valve implantation, especially when using a balloon expandable system (Edwards SAPIEN™), can be performed in a stepwise manner, which allows for some slight adjustments during balloon dilatation thus obtaining a perfect position. We believe that this technique is advantageous and should always be performed. It was first applied by our team in February 2008 to treat a patient where valve-in-valve (SAPIEN™ in SAPIEN™) was required11, and this was later described by colleagues from Berlin12.

More recent TA application systems, which include a nose cone, will allow physicians to use the antegrade TA approach without previous balloon dilatation, thus inserting the valve directly to simplify the procedure further.

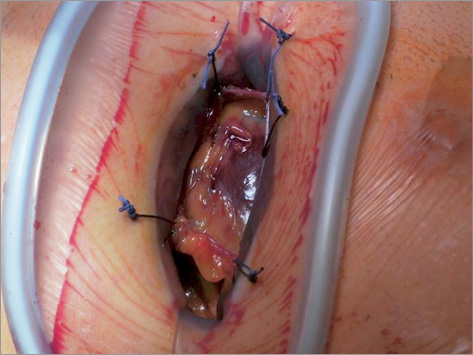

Other approaches aim at optimising the antegrade TA access technique further: whereas a conventional small retractor was used to spread the intercostal space slightly to gain better access to the pericardium and apex (Figure 1), a non-rib-spreading approach, currently a soft tissue retractor only is being used (Figure 2). This will certainly be another step forward to minimise the surgical trauma further and thus improve patient outcomes. Initial clinical experience with this non-rib-spreading TA approach is quite positive, allowing for all steps of the procedure to be performed in a controlled manner. Patients will certainly have even less discomfort from pain, which of course will have to be proven by further clinical evaluation.

Figure 1. Transapical access – conventional approach (purse-strings + metal rib retractor).

Figure 2. Transapical access – “non-rib-spreading technique” (purse-strings or closure device + soft-tissue retractor only).

Another step forward will be the use of standardised access and closure systems. This will certainly be of clinical value as soon as a very safe and standardised access and closure can be accomplished in every patient and quite independently from the individual skills of the surgeon. The ultimate goal in this direction, however, is a truly percutaneous access and closure. Some of the current techniques aiming in these directions will be highlighted later in this manuscript.

TAVI in general and the TA technique specifically have been implemented in parallel with using advanced and three-dimensional imaging techniques in the operative scenario13. Optimised imaging, together with the TA technique, even enables anatomically correct valve implantation, thus matching valve commissures to native commissures14. The feasibility of placing a transcatheter prosthesis in an anatomically correct position is the most unique feature of the antegrade TA approach, due to its short and direct access and thus its overall simplicity.

The valve-in-valve technique was successfully evaluated experimentally and then introduced into clinical practice using the TA approach15-18. In addition to easily reaching the aortic valve, mitral valve disease can also be treated through the TA approach.

The antegrade TA approach resulted in the clinical introduction of several new second-generation TAVI devices such as the Engager™ valve19 (Medtronic), the JenaValve™20 (JenaValve Technology GmbH, Munich, Germany) and the ACURATE™ valve21 (Symetis, Ecublens, VD, Switzerland), all three providing correct commissural alignment of the implanted prosthesis. This may lead to a further enhanced safety profile of the procedure, due to the clear avoidance of any coronary artery obstructions. The presence of several CE-approved TA devices can be seen as a clear indicator for the ease of this antegrade direct approach.

TA literature results and comparison to other approaches

Based on the standard TA technique that has evolved over the years, very reliable and strong clinical evidence underlining the benefits of this approach has been published. Over the years the TA approach has gained broad acceptance by many Heart Teams. After initial success, acceptable multicentre outcomes were published on high-risk patients4. Later on, good comparability was proven for the initial 100 patients in relation to conventional surgery by means of a propensity score analysis22. Meanwhile, good three-year outcomes in 299 patients treated in the years 2006 to 20097, as well as improved knowledge on specific factors, have been noted23. Excellent longer-term outcomes of the TA approach have also been documented by other sites, especially when using a dedicated approach24. In parallel to introducing new devices into clinical practice by means of the antegrade TA approach19-21, the next generation of the initial transapical prosthesis, the SAPIEN XT™ valve, was introduced successfully. This was demonstrated by good multicentre outcomes in high-risk patients25. In addition, the new 29 mm prosthesis, offering further therapeutic options for the elderly and high-risk patients, was introduced with good results in this study25. In addition to these studies, multicentre registries clearly demonstrated the strengths of the TA approach in elderly and high-risk patients with AS26.

When evaluating clinical results from different studies and registries it has to be kept in mind that they are very dependent on patient-related factors such as the number of comorbidities and the overall individual risk profiles. In addition, patient selection has a major impact on the overall outcomes. Some of the specific risks a TAVI procedure may have are not even captured when using the classic risk scoring systems, such as the EuroSCORE or the STS score or even the new German aortic valve score. Therefore, clinical assessment by the Heart Team plays the most important role on direct outcomes for the patients.

Many larger studies and registries, such as the US PARTNER trial for example, may reach the conclusion that the TF approach is associated with better outcomes than the TA approach. However, since a clear “TF first” strategy was used in this trial, patient selection was the decisive factor on outcome. In addition, site experience, i.e., having performed at least one hundred procedures with the same team to gain some experience, is another very important contributing factor on outcome. Interestingly, a recent registry publication, quoting initially improved outcomes for the TF approach, later came to the conclusion that the larger number of contributing risk factors was the decisive factor for overall outcomes27.

We are convinced that a more frequent use of the advantageous and antegrade TA technique would lead to further improvement in outcomes due to greater experience at some sites. In addition, it would even lead to lower TF complication rates, especially when all procedures are performed by a Heart Team and there is no need to push the limits for a TF approach but instead use the sometimes easier TA approach.

Very interesting results were reported in the Canadian multicentre evaluation28. There were similar outcomes for both groups receiving TF or TA TAVI, two, three and four years post implantation. This is quite remarkable, because patients in the TA group had a significantly higher risk profile according to an STS score of 10.5% versus 9%. Thus the results in this trial were similar after TF versus TA at one, two and three years, despite a significantly higher risk profile not in favour of TA: what would the outcomes have been if similar risk patients had been treated?

To summarise the outcomes in the literature, the TA approach has proven several benefits and good clinical outcomes in elderly high-risk patients with AS. This was documented by single-centre and multicentre clinical trials as well as multicentre registries. Newer devices were successfully introduced into clinical practice using the TA approach over the years. There is no prospective randomised clinical trial comparing the antegrade TA and the retrograde TF techniques. Therefore, due to the obvious advantages of the TA approach, it should be used frequently, especially as there is no clinical evidence to support a “TF first” patient selection strategy.

When evaluating the literature, the overall risk of stroke should not be forgotten: many series and registries show almost comparable stroke rates for the TA approach in the presence of higher risk profiles. This could be judged as a superior outcome if comparable patients were treated. By means of a recent meta-analysis, these strengths of the TA approach, i.e., a clearly lower stroke rate, were well documented29. Lower stroke rates with the TA approach may result from less manipulation on the aortic arch as well as the overall simplicity of the antegrade technique.

Enabling standardised TA access and closure

Current TA techniques rely strongly on mini-thoracotomy access, conventional rib spreader or less invasive soft tissue retractor exposure of the apex and conventional purse-string or mattress sutures to secure the apical puncture site. Future clinical strategies aim towards further standardisation of the TA access and closure in order to obtain an even easier procedure. The different approaches which are presently in clinical trials focus on suture-based techniques, non-suture metal inserts, occluder-like devices or elastic structures. We will try to introduce briefly the Apica ASC™ system, as well as Permaseal, Entourage and CardiApex.

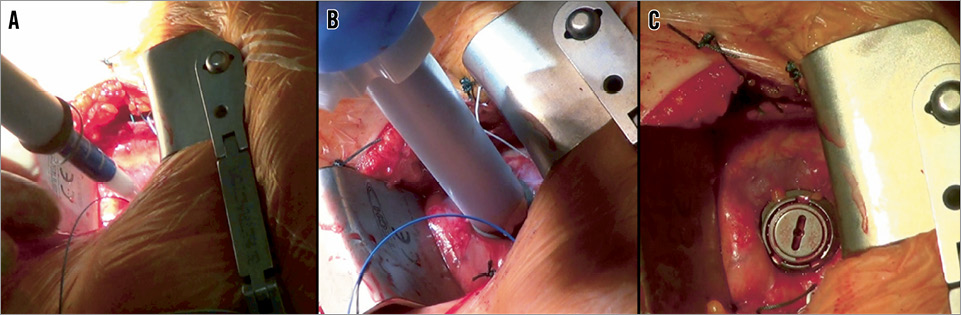

Apica (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Apica ASC apical closure device: A) device “over-the-wire” preloaded with TAVI sheath; B) anchoring of the “sealing coil”; C) after “closure plug” deployment.

The current system is being used with conventional mini-thoracotomy and after opening the pericardium. The Apica device (Apica Cardiovascular Ltd, Galway, Ireland) is engineered from metal and consists of a coil that is inserted into the myocardium. The system is loaded with an introducer sheath of a transcatheter valve before insertion. Later on a closure cap is inserted into this canal. The initial clinical multicentre trial enrolled 32 patients: all were treated with the Edwards SAPIEN valve by means of an Ascendra sheath (both Edwards Lifesciences). Initial clinical experience was promising, and the results of the first ten patients were recently published30. Data from clinical cases were submitted recently to obtain CE approval. Further miniaturised systems, especially for percutaneous application, are under development.

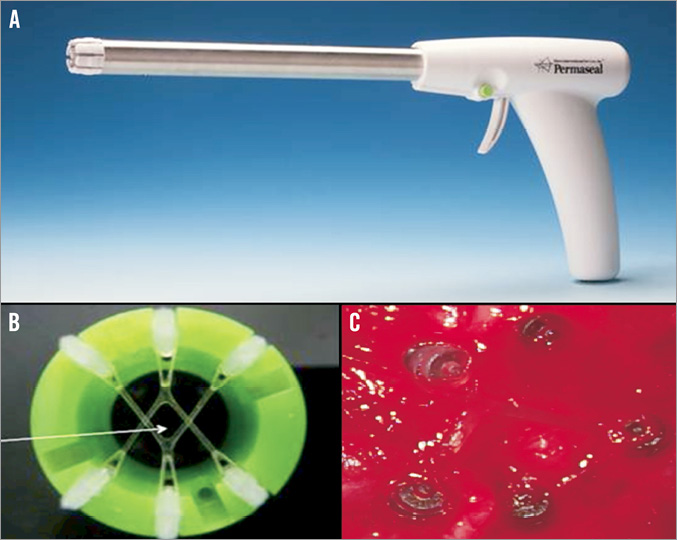

Permaseal™ (Figure 4)

Figure 4. MID Permaseal apical closure device: A) deployment “gun” to fire myocardial anchors; B) & C) “operating window” created by myocardial anchors (self-closing).

Similar to the previous device, Permaseal™ (Micro Interventional Devices, Bethlehem, PA, USA) is presently used after conventional mini-thoracotomy access to the left ventricular myocardium. Six anchors, three of which are connected with elastic V-stays, are fired into the myocardium, followed by over-the-wire sheath and valve insertion. After retrieval the puncture site should close spontaneously by means of the elasticity of the V-stays. Initial clinical experience was gathered and some redesign of the system is currently under way.

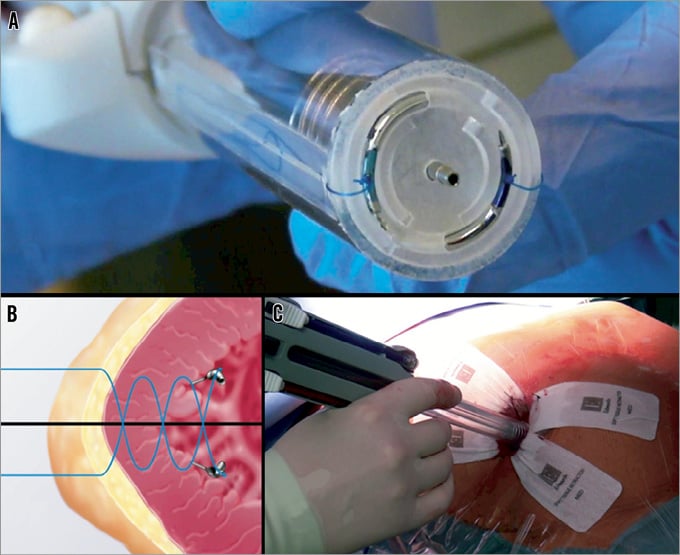

Entourage CardioClose™ (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Entourage CardioClose™ apical closure device: A) suture deployment device; B) helical double suture concept; C) device used with a “non-rib-spreading” approach.

The Entourage system (Entourage Medical Technology, Menlo Park, CA, USA) acts with two sutures, which are inserted into the myocardium by means of a double helical needle and 2.5 turns. Anchors should suspend the sutures as soon as the needle is retrieved. At present, conventional TA access by means of an anterolateral mini-thoracotomy is used. Initial patients have been included into clinical feasibility trials.

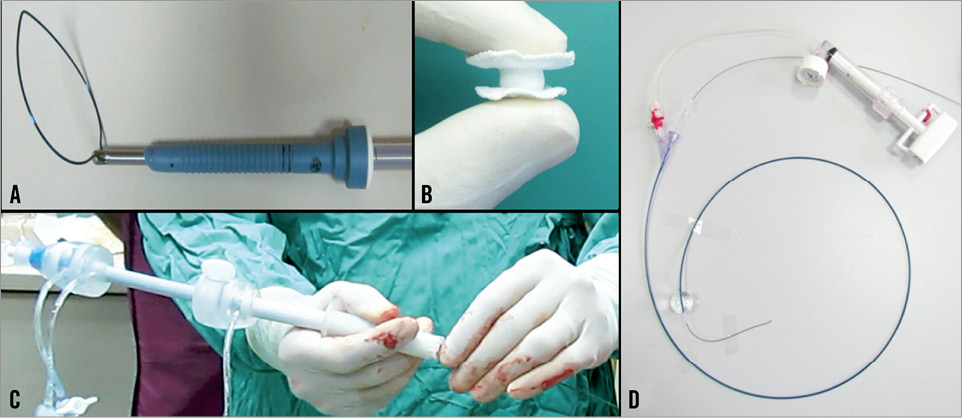

CardiApex (Figure 6)

Figure 6. CardiApex apical access+closure device: A) percutaneous trocar + snear; B) double-disc closure; C) access sheath; D) “inside-out” puncturing catheter.

The CardiApex system (Cardiapex Ltd, Or Akiva, Israel) is based on a completely different concept. In an initial step a specific balloon is inserted through a 9 Fr femoral sheath and placed in the apex of the left ventricle. Then in-out puncture with a needle included inside the balloon is performed, followed by Amplatz Super Stiff guidewire placement. This guidewire is captured using a snare which is inserted through a 10 mm trocar in the sixth intercostal space at the apical region. Over the wire and through the trocar a special sheath is inserted, having an external suction cap at the pericardium and an inner balloon in the left ventricle, which is then inflated after deflation of the initial balloon, thus stabilising the myocardium in a sandwich-like fashion. Routine TAVI procedure is performed through the sheath. Thereafter an umbrella-like closure plug is used. The system allows for completely percutaneous access and closure. Initial procedures have been performed on patients and some redesign of the system is under way.

In summary, TA access and closure systems will allow for standardised access and closure which should be very reliable in the near future. This will further ease the TA procedures and pave the way towards a completely percutaneous TA procedure.

The beauty of the TA approach / perspectives

The transapical access for TAVI is just an intuitively simple and safe procedure yielding multiple options for the Heart Team: it allows for safe placement of established devices, and in addition for the safe introduction of newer iterations of established devices as well as for the introduction of second and third-generation TAVI systems. This is all due to its intuitive simplicity: being an antegrade technique together with a short distance to the aortic valve the TA approach allows for specific manipulations to position the valve very exactly. Coaxial alignment as well as commissural (anatomical) orientation of a prosthetic valve can be easily accomplished. For the patients’ benefit these procedures are associated with a low stroke risk. Multiple therapeutic options do and will evolve from the TA approach. Further therapies to treat aortic valve disease, but also the therapy of mitral valve disease, insertion of assist devices, or combinations of these, will gain increasing acceptance.

Another beauty of the TA approach is that there is no real limitation in sheath diameters, especially when newer systems with additional features, for example advanced solutions to treat paravalvular leakage, or mitral valve prostheses, become available. Vice versa, the prospects of transapical access and closure systems will allow for truly percutaneous antegrade access and closure in a very standardised manner in the future.

Literature results may indicate that other approaches, especially the TF approach, are superior to the TA approach. This is certainly incorrect, because patients with different underlying comorbidities cannot be compared effectively. The use of a “TF first” approach as in many centres clearly leads to specific patient selection and thus to differences in outcomes. There are data indicating that TA leads to similar outcomes several years after the procedures despite a significantly higher risk profile. This could be extrapolated into superior outcomes if similar risk patients were treated.

The beauty of the TA approach is that it is an antegrade approach for the Heart Team, performed by cardiac surgeons and cardiologists. Heart Team physicians will know about its intuitive benefits.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.