“I am a slow walker, but I never walk back.”

Abraham Lincoln

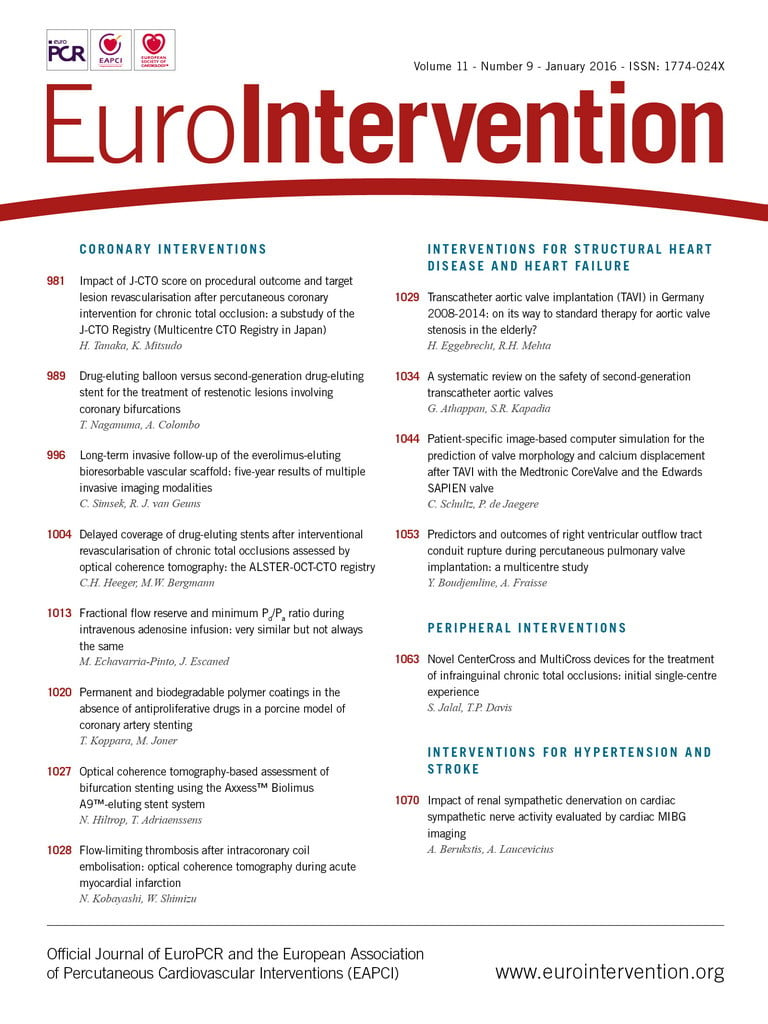

Since Professor Alain Cribier first performed a transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in June 20021, TAVI has emerged as a safe, effective, and widely practised intervention that has transformed the lives of hundreds of thousands of patients worldwide2 and has answered an unmet clinical need as TAVI is now the standard of care for inoperable patients and the preferred therapeutic option for high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis3,4. Moreover, transcatheter heart valve (THV) technology has expanded well beyond Professor Cribier’s initial intentions, and is frequently applied to a variety of off-label patients (intermediate/low-risk)5, pathologies (bicuspid aortic valve; aortic regurgitation)6, and clinical situations (valve-in-valve; valve-in-ring)7. The adoption of novel medical technologies such as TAVI is determined by a variety of factors, including national political and financial concerns, healthcare policy, population density and age profile, reimbursement strategies, and cultural factors2. In Germany, these factors seem to have aligned: Europe’s most populous nation has implanted more THVs than any other nation since commercialisation in 20072.

In this edition of the Journal, Eggebrecht and colleagues detail the astonishing adoption kinetics of THV technology in Germany8. Using data derived from the independent Institute for Applied Quality Improvement and Research in Health Care (AQUA, Göttingen, Germany), these authors describe a 20-fold increase in annual THV implants between 2008 (N=637) and 2014 (N=13,264), with year-on-year implant growth of 15-25%. When population data are considered, Germany performs 164 TAVI cases per million inhabitants (Ireland currently performs 23 implants per million). Using restrictive evidence-based indications available in 2012, Osnabrugge et al estimated the annual number of new TAVI candidates in Germany would approximate 3,952 (95% confidence interval: 1,684-7,227)9; clearly, these restrictive practice patterns are not followed in Germany.

In 2008, 11,842 procedures (TAVI and surgical aortic valve replacement [SAVR]) were performed for isolated aortic valve disease in Germany. In 2014, this number had doubled to 23,217. These data, and the observation of a marginal reduction in isolated SAVR volume (5% since 2009), suggest that TAVI is actually being applied to the patient population for which it was initially intended, i.e., the 30-50% of patients denied SAVR due to advanced age, comorbid conditions, frailty, and poor left ventricular function10. In 2012, we estimated that only 42% of TAVI candidates in Germany actually received a transcatheter heart valve2. Applying the implant data provided by Eggebrecht et al, and using the same restrictive indications and post-TAVI outcome data that were available in 2012, this figure increases to 109% in 2014. This estimate supports the evidence of an “indication creep” towards the treatment of lower-risk patients in Germany, as demonstrated by a gradual reduction in the logistic EuroSCORE over time. It is noteworthy, however, that the age distribution of TAVI candidates in Germany has remained constant since 2008.

Rapid proliferation of TAVI has been labelled costly and potentially detrimental to patient care11. Foremost among the explanations for such rapid TAVI adoption in Germany was the introduction of a diagnosis-related group (DRG)-based reimbursement system in 2010, though accumulating physician experience and patient preference for a less invasive strategy may also have driven TAVI utilisation. Moreover, the short report by Eggebrecht documents impressive reductions in TAVI-related complications, including stroke and mortality to surgical levels, despite the higher risk profile of the TAVI cohort. Such results, when applied to an elderly patient population, even one of lower risk, affirm the responsible proliferation of TAVI technology in Germany.

It is fascinating to behold that, within six years of commercialisation (2013), the number of TAVI cases (N=10,441) surpassed SAVR numbers (9,899): 50 years of surgical progress surpassed numerically in four years! What are the implications for the future of SAVR? With clear evidence of intermediate and lower-risk patients already being treated by TAVI in Germany, accumulating evidence of THV durability, and the imminent publication of randomised studies in lower-risk cohorts, it is likely that the gradual decline in isolated SAVR volumes will continue. SAVR will of course continue to play a vital role in the treatment of patients with concomitant severe coronary artery disease, infective endocarditis, and multivalve pathology. Expansion of THV technology to bicuspid aortic valve disease also remains contentious, though new-generation THVs may overcome the specific anatomical hurdles associated with this pathology12.

Ultimately, the individual patient must remain at the centre of our treatment decisions, and, as TAVI adoption continues to expand, it should continue to be scrutinised at both local and national level, to ensure appropriate patient selection and robust clinical outcomes. Our German colleagues are to be congratulated for the widespread dispersion of TAVI technology, for treating elderly and frail patients who would otherwise remain untreated, for the excellent clinical outcomes documented in this report, and indeed for the collection of such robust data. Their efforts offer a glimpse into the future of aortic stenosis management worldwide.

Conflict of interest statement

D. Mylotte has no conflicts of interest to declare. N. Piazza is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Medtronic and a consultant and equity shareholder with HighLife. P.W. Serruys has no conflicts of interest to declare.