Valvular heart disease (VHD) is now regarded as a major public health problem with high mortality across the world. The prevalence of VHD has been shown to be 13.2% at age >75 with a predominance of degenerative lesions in a U.S. population-based study1. In contrast, rheumatic heart disease remains the leading cause of VHD in developing countries (e.g., South Africa, Turkey, India, etc.)2,3,4. With population ageing and economic as well as healthcare development, the burden of degenerative VHD in the elderly is likely to keep growing in developing countries.

Open heart surgery was the treatment of choice for VHD patients, but at least one third of patients were deemed inoperable due to comorbidities, poor cardiac function and advanced age5. Transcatheter valve interventions provide minimally invasive treatment options for these patients. The first-in-man transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in 2002 blazed a trail in transcatheter aortic valve therapy6. Since the first Asian implant in Singapore in 20097, TAVI has spread from West to East and become a well-established therapy for elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) after decades of development in transcatheter devices and techniques.

TAVI volume across the continents

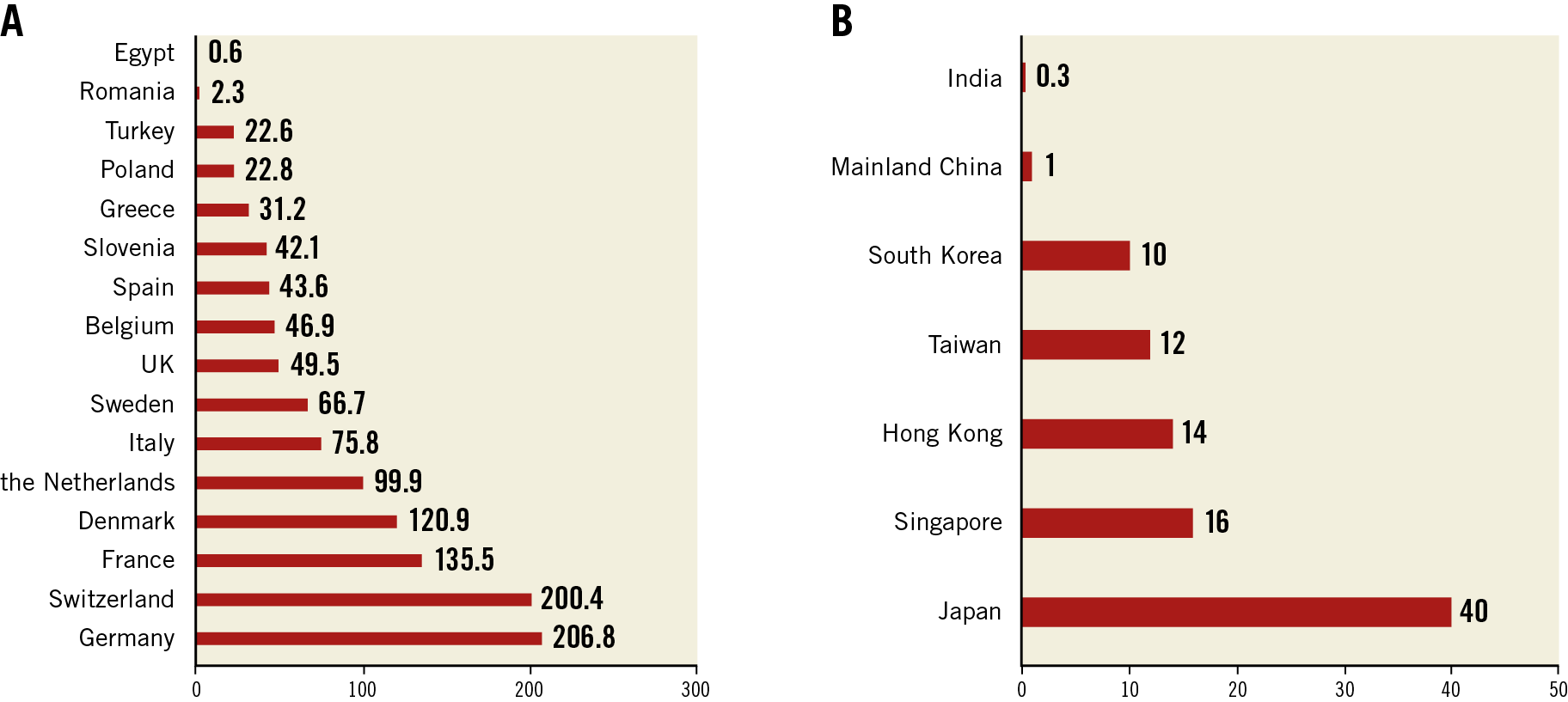

The recently published European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions Atlas survey demonstrated that the annual median of 48.2 (interquartile range 29.1-105.2) TAVI procedures per million people was performed in 16 European Society of Cardiology member countries, varying from <25/million in Egypt, Romania, Turkey, and Poland, to >100/million in Denmark, France, Switzerland, and Germany8. A similar international heterogeneity in TAVI volume can also be seen in Asia from published reports. The number of annual TAVI cases has reached 40/million in Japan and 10-20/million in South Korea, Singapore and regions of Hong Kong and Taiwan9. In comparison, the corresponding figure was 1/million in mainland China in 2018, while TAVI is still at the nascent stage in other developing Asian countries (e.g., 400 TAVI implants in India in 2018, etc.) but shows increasing momentum10 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Annual transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) procedures per million people in different European Society of Cardiology member countries (A) and Asian regions (B) (2016 or latest year).

This disparity in TAVI volume is associated with national economic resources and technological investment to develop novel medical services8. As for lower income countries such as China and India, the uptake of TAVI is mostly hindered by high device cost with poor reimbursement and also the lack of professionals and specialised Heart Teams. If the costs could be reduced and if standardised training programmes could be established, it would be possible to increase the volume of procedures substantially.

TAVI outcomes and anatomy in the West and East

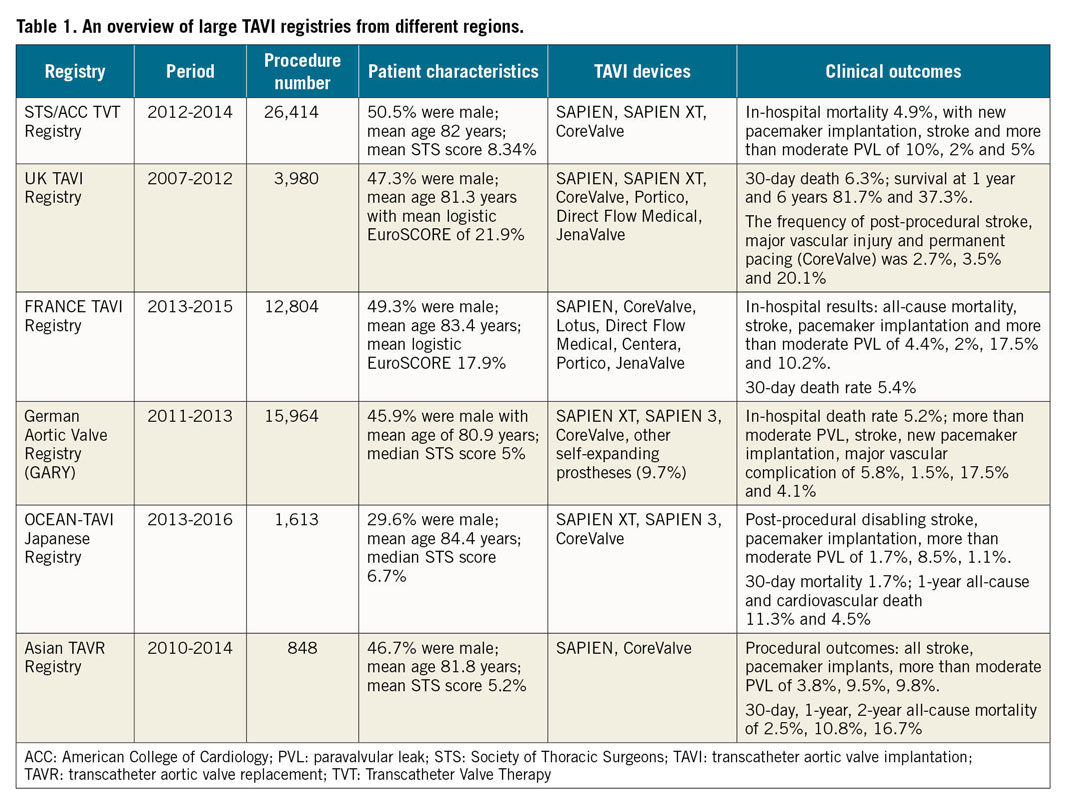

According to the published national registries, the post-TAVI clinical results are reasonable and comparable in the USA, Europe and experienced Asian countries11,12,13,14,15,16. The details of several large registries are summarised in Table 1. Nevertheless, specific anatomic features have made TAVI challenging in Asia. First, the average Asian physique is significantly smaller than that of Western people. Small annulus and vascular access dimensions as well as low coronary heights were reported in the Optimized transCathEter vAlvular iNtervention (OCEAN-TAVI) Japanese registry, which might increase the risk of complications and calls for smaller devices17. The newer-generation SAPIEN 3 valve (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) with a smallest size of 20 mm and the delivery sheath reduced to 14 Fr was launched in Japan in 2016. Promising outcomes have been presented18. More Asians with a small body size could benefit thanks to the improved device design.

A high proportion of patients with a bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) was observed in China (≈50%) and India (≈34%), possibly due to the younger TAVI population compared to the Western world10,19. BAV is commonly accompanied by an asymmetrical annulus, heavy calcification and aortopathy; therefore, this type of anatomy is considered difficult when performing TAVI19. To optimise the device size selection for TAVI candidates with BAV, several sizing strategies have been proposed including supra-annular sizing, sequential balloon sizing and intercommissural distance measurement20,21,22. In addition, domestic valves have emerged with high radial force to improve expansion in BAV, such as the self-expanding Venus A-Valve® (Venus Medtech, Hangzhou, China) and the balloon-expandable Myval™ valve (Meril Life Sciences, Vapi, India). Nowadays, Chinese Heart Teams have the greatest experience with TAVI in BAV, mostly using indigenous devices. A multicentre registry in China will be initiated soon to demonstrate TAVI performance further in patients with BAV.

Last but not least, rheumatic AS is still highly prevalent in many Asian countries and is regarded as a relative contraindication for TAVI due to the lack of calcification for anchoring the transcatheter devices. At our institute, TAVI with the self-expanding prosthesis appeared to be feasible and safe in patients with non-calcific AS23. Case reports from other regions have also shown successful TAVI in rheumatic AS24.

Overview of transcatheter devices

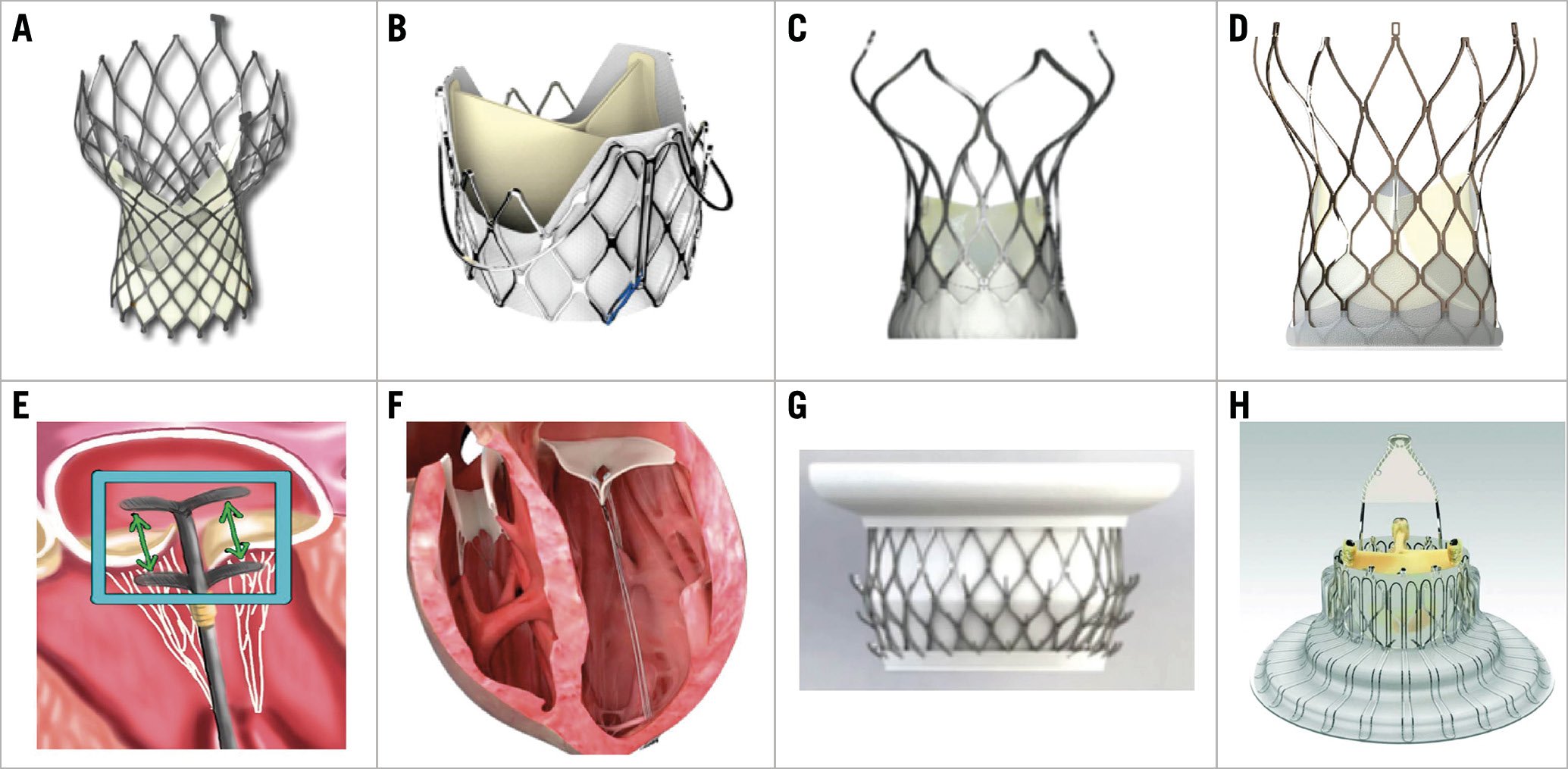

Over the past few years, various dedicated devices have provided individualised choices for TAVI candidates. Except for the Evolut™ R/PRO (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and SAPIEN 3 valves, both with U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in low-risk patients, other valves such as the LOTUS Edge™ (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA – U.S. FDA approved April 2019), the ACURATE neo™ (Boston Scientific) and the Portico™ (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) are now available for the Western population. As for China, after the first transfemoral Venus A-Valve and transapical J-Valve™ (JC Medical, Inc., Suzhou, China) were approved in 2017, the VitaFlow® valve (Shanghai MicroPort CardioFlow Medtech, Shanghai, China) came onto the Chinese market in 2019, and the TaurusOne® valve (Peijia Medical, Suzhou, China) has completed its pre-market clinical trial (Figure 2A-Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Domestic Chinese devices for transcatheter valve interventions. A) Venus A-Valve. B) J-Valve. C) VitaFlow valve. D) TaurusOne valve. E) ValveClamp. F) MitralStitch. G) Mi-thos. H) LuX-Valve.

Transcatheter mitral valve therapy and tricuspid valve therapy are also presently booming but are not such common practice as TAVI, especially outside of Europe and the USA. In terms of devices, the MitraClip® system (Abbott Vascular) is still the only one approved by the U.S. FDA for patients with degenerative and functional mitral regurgitation. The Tendyne valve (Abbott Vascular) won the first CE mark for a transcatheter mitral valve replacement device in January 2020. In addition, the TriClip (Abbott Vascular) and PASCAL (Edwards Lifesciences) systems have just been approved for commercial use in Europe this year as the first clip-based tricuspid valve repair devices. Concerning Chinese innovations in this field, multicentre pre-market clinical trials (NCT03869164, NCT04080362) have started for the transapical edge-to-edge repair device ValveClamp (Hanyu Medical Technology, Shanghai, China) and the MitralStitch™ (Valgen Medtech, Hangzhou, China) which provides both edge-to-edge repair and chordal replacement. The first-in-man implantation of the transvenous mitral valve repair device DragonFly™ (Valgen Medtech) was recently performed25. Moreover, the transcatheter mitral and tricuspid valve replacement devices Mi-thos® (NewMed Medical, Shanghai, China) and LuX-Valve (Jenscare Biotechnology, Ningbo, China) have been evaluated successfully in clinical cases26,27 (Figure 2E-Figure 2H).

As they are techniques with quick recovery and minor wounds, structural transcatheter interventions are gaining increasing popularity in other regions including South Africa and Latin America28,29. To educate and train interventionists with sufficient skills for performing catheter-based valve therapy, multiple international valve conferences and workshops have been organised (e.g., PCR Valves e-Course, PCR Tokyo Valves, PCR-CIT China Chengdu Valves, TAVI Workshop in Latin America, etc.), which are also platforms for sharing experience and strategies regarding different ethnic groups. Together with improved regulations on novel device approval and reimbursement, as well as validated domestic products, transcatheter valve treatment will hopefully become feasible and affordable to a larger population. The great efforts of both industry and interventional cardiologists will continue to bring innovations to this field, thus enabling the treatment of patients with diverse characteristics in the future.

Conflict of interest statement

M. Chen is a consultant/proctor for Venus MedTech and MicroPort. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.