The first human case description of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was published in 20021 and the first randomised controlled trial followed in 20102. Similarly, the first human transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) procedure (using the “edge-to-edge” technique) was performed in 2003 and the first randomised controlled trial published in 20113. Thus, it took eight years for each procedure to be translated from a promising concept into evidence-based medicine: if we visualise TAVI and TMVR as two trains running on parallel tracks, one would say that they ran the first part of their journey at the same speed. However, the similarities end here.

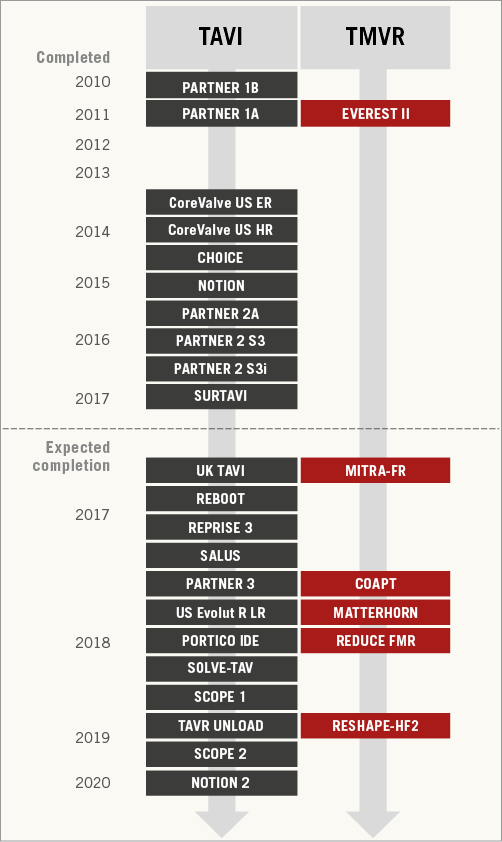

Approximately 15 years since the first human procedures, the role of TAVI and TMVR in present day daily routine –as illustrated by guidelines on both sides of the Atlantic– is extremely different. Waiting for new European recommendations for management of valvular heart disease later this year, TAVI is already the “standard of care” for inoperable patients and an alternative to surgery for subjects at high risk4,5. In contrast, what is TMVR? It is “only” a IIb recommendation for inoperable subjects with severe degenerative mitral regurgitation, according to the American guidelines5. In addition, if we base our reasoning on the number of new studies performed since the publication of current guidelines –or upcoming studies in the pipeline– the midterm outlook of TMVR appears rather less exciting than that of TAVI (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Timeline of published and selected ongoing studies of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) and transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR). For unpublished studies, the estimated primary completion date (final data collection date for primary outcome measure) is indicated as reported by the investigators in the clinicaltrials.gov or isrctn.com database.

Indeed, with similar outcomes compared to surgery in intermediate-risk patients6 and new trials ongoing in low-risk patients7, the TAVI train travels fast. The only possible snag on the horizon, i.e., concerns over the actual durability of TAVI outcomes, is currently out of the question, pending the very long-term follow-up from landmark trials and dedicated prospective investigations8. On the other hand, the randomised evidence generated so far in the TMVR universe is limited to the first and only trial of the edge-to-edge technique3, and ongoing randomised investigations of this and other TMVR procedures are facing significant challenges in recruitment, with some awaited TMVR trials (NCT01772108, NCT02534155) even being prematurely terminated.

In this issue of EuroIntervention, we publish the second part of a survey promoted by the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) on the current status of transcatheter valve therapies in Europe9. The first part, dealing with TAVI, was the subject of an earlier publication by the journal10. This second part now complements that report by offering an interesting snapshot of the current adoption of TMVR in Europe. It is by comparing the results of the two TAVI and TMVR surveys that one realises how much these therapeutic approaches to valvular heart disease are actually progressing at different velocities and degrees of acceptance by the interventional community. For example, of 176 European centres responding to the EAPCI survey and running a TMVR programme, about three quarters performed fewer than 40 procedures in 2014, and about 60% fewer than 10. More than 80% of centres performing >40 procedures were located in Germany. The authors interpreted these findings as the expression of the “marginal” penetration of TMVR in Europe, for reasons identified in a broad array of “economic, regulatory and logistic issues, […], along with the lack of compelling studies and clear indications”. Interestingly, the main barrier for centres that did not have and did not plan to initiate a TMVR programme at the time of responding to the survey was associated more with reimbursement rather than the lack of sound and compelling scientific evidence in support of TMVR.

The survey published by the same EAPCI task force late last year reflects more geographical diversity for centres performing TAVI in Europe (with Germany again taking the lead) and supports in general the concept of a much faster adoption rate than TMVR, with one fifth of centres having already performed >500 procedures from the time of initiating their programme to the time of responding to the survey10. The TAVI article also highlighted room for improvement and areas of uncertainty, but it is indisputable by comparing the two papers that TMVR and TAVI are advancing in different ways: one slowly, the other exponentially9,10.

However, it would be unfair to attribute the “dual velocity” of these procedures to different interest or the ability of manufacturers and investigators to develop clinically one therapy more than the other. Visibly, the truth lies in the diversity of the physiopathological question at play. A successful analogy that circulates among interventionalists is that “TAVI addresses aortic stenosis like a corkscrew addresses a bottle of champagne”. In contrast, TMVR tackles just one part of the problem, as it is increasingly recognised that the mitral valve is not just a valve, but rather an “apparatus”. In other words, while TAVI is successful at changing the prognosis of severe aortic stenosis, TMVR –as it stands now– does not seem to be as good at changing the prognosis of the failing left ventricle, an issue that also complicates the conduct and interpretation of studies on this subject11. Functional mitral regurgitation is the primary reason for TMVR in Europe. Despite this, no randomised study is available yet to provide compelling evidence of its superiority over conservative management (the COAPT, RESHAPE-HF 2, and MITRA-FR trials are ongoing, the results of which will hopefully support practice in this setting).

Based on the above, one would say that the real clinical and investigational challenge represented by mitral regurgitation has been underestimated, and that meaningfully addressing this complex condition requires something more than a clear-cut technological solution. It gives hope for the future of the field to note that guidance on trial design and endpoint standardisation is now available for TMVR as well12,13, and reassuring to appreciate the level of interest and competency surrounding the potential of this therapy and its future iterations (not to mention transcatheter mitral valve replacement) in interventional meetings14. TMVR is alive and eager to explode as TAVI did before, but it will take time and some kind of going “back to the drawing board”. Deeper understanding of the physiopathology and the natural history of the disease before and after transcatheter mitral valve therapies –in collaboration with echocardiographers, heart failure specialists and other professionals– will be key to making significant progress in this field, and make the TMVR train pick up speed again.