Abstract

The field of valve intervention is rapidly changing. Clinical practice guidelines are based on evidence and practical clinical experience. The randomised trials considered for the guideline recommendations regarding indications for TAVI cover the high-risk and intermediate-risk subgroups of patients. With new evidence for low-risk patients, consideration has to be given to discussing TAVI as the default strategy in the majority of patients. This is a paradigm shift from the established practice. More than ever, the patient will be at the centre of the decision making. The Heart Team is essential for optimal patient pathways, as patient factors, longevity and durability considerations have to inform the discussion. Further developments discussed in this article revolve around evidence on secondary mitral regurgitation and mitral edge-to-edge repair.

Introduction

Valve replacement and repair used to be a surgical domain. With the advent of interventional techniques, namely transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) and edge-to-edge mitral valve repair, new treatment options have entered the clinical arena for the benefit of large patient groups.

The implementation of new interventions follows a pattern of innovation, first-in-man trials, larger-scale prospective trials, and then often randomised controlled trials to assess the value of a new technique compared to the current standard. The broad adoption of a new clinical technique is usually based on reported experience in high-volume pioneering centres and the evidence gathered in randomised trials and summarised in expert guidelines.

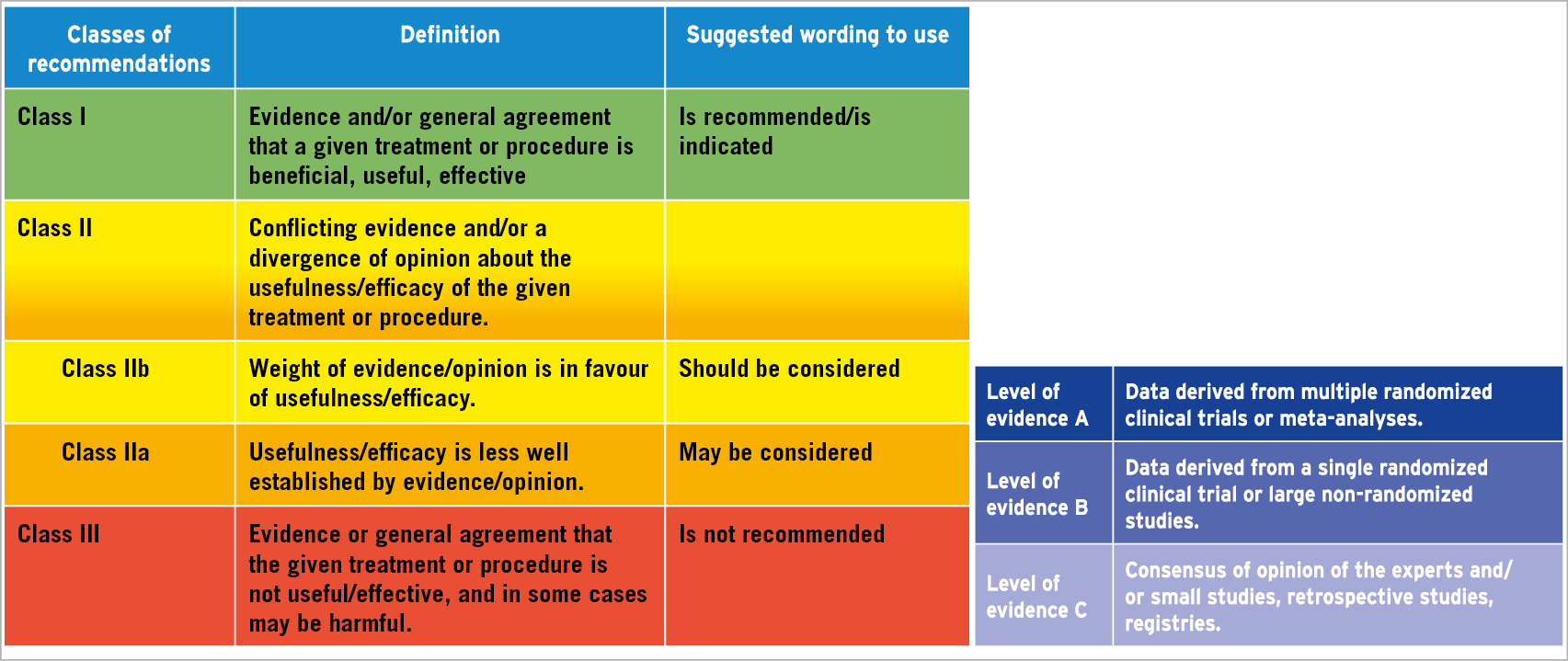

Whilst guidelines can give recommendations based on the opinion of the writing committee (level of evidence C), the strongest recommendations will invariably be based on single or multiple randomised controlled trials (level of evidence B and A). The classification of recommendations used in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines is shown in Figure 1. In their current format, the guidelines issued by the European and American societies undergo revisions in four- to five-year cycles. As a result, practice can change in the interim, based on trial results, and new paradigms can evolve making existing guidelines outdated and create a need for discussion of the future recommendations for best practice.

Figure 1. The classification of recommendations used in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines. (Reproduced with permission from EuroIntervention6).

In this article we will review the development of guidelines since the advent of trial evidence for TAVI and edge-to-edge repair, focusing on existing guidance and the changing paradigms in valvular heart disease treatments that are a result of recent evidence.

THE PAST

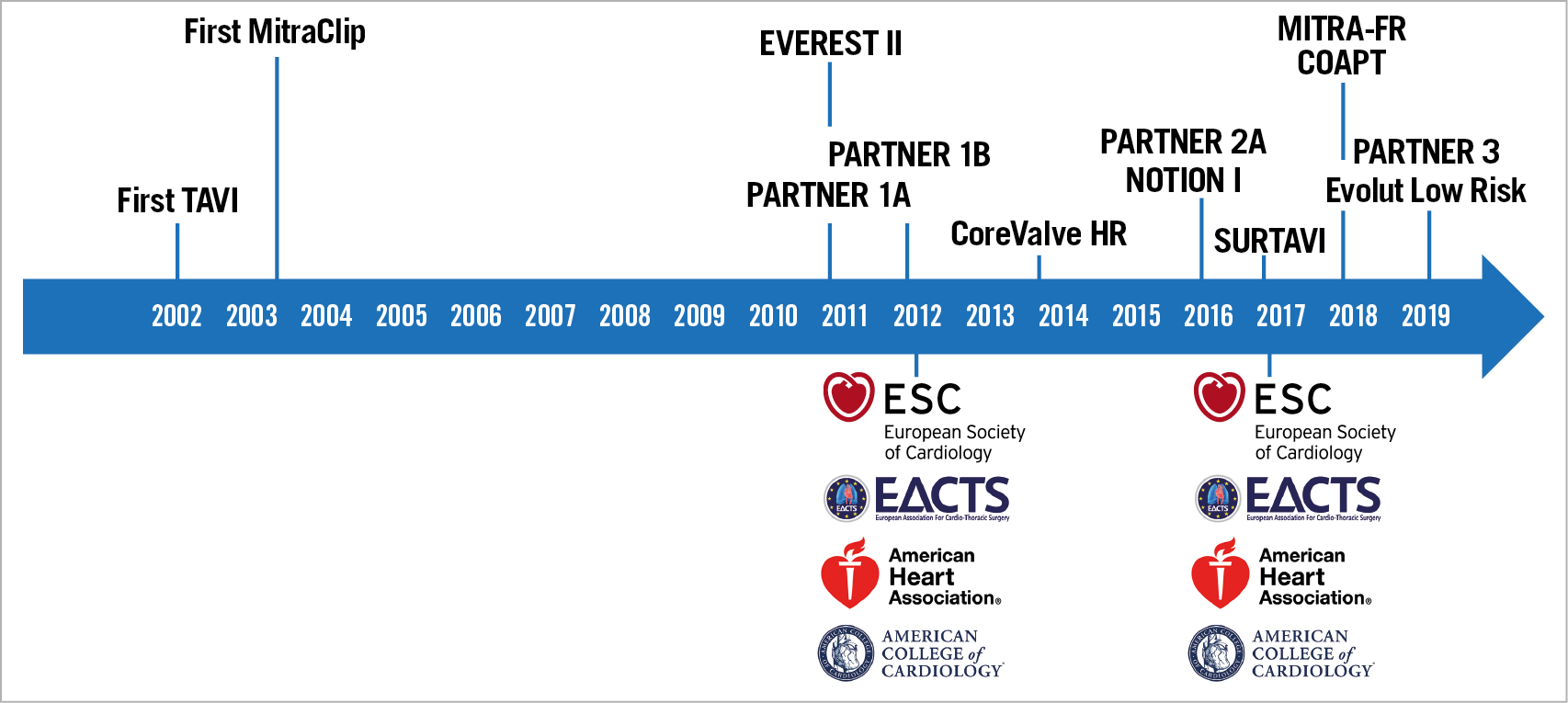

The first percutaneous aortic valve implantation was carried out in 20021. The PARTNER 1A and 1B randomised controlled trials to prove the benefit of TAVI in patients who could not undergo surgery or were at very high surgical risk were published in 2010 and 20112,3. Figure 2 shows the timeline from first procedure performed to the current guidelines.

Figure 2. Timeline: evidence and guidelines.

The 2012 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on valvular heart disease4 were the first to recommend percutaneous treatment options for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. This was a document that was produced jointly by cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, emphasising the dialogue and discussion required to find the best treatment pathways for optimised individual patient benefit. The Heart Team approach, initially suggested by the 2010 ESC Guidelines on myocardial revascularisation5, was adopted.

TAVI was recommended in centres where a Heart Team was actively involved in the treatment decision (class I, level of evidence C), and only in centres with cardiac surgery on-site (class I, level of evidence C). As a result of only one single randomised trial available for the patient groups unsuitable for surgery3, and at high surgical risk2, the level of evidence here was B. Following PARTNER 1B, there was a clear class I recommendation for TAVI in patients who cannot undergo surgery. For the high surgical risk cohort, the recommendation was IIa B, for a Heart Team decision as to the preferred treatment strategy. The risk at that time was mainly defined by surgical risk scores, and levels of logistic EuroSCORE I >20% and STS score >10% were seen as high risk.

The choice of prosthesis for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has to reflect the expected durability and the risk of a potential reintervention. Whilst there were reports of successful valve-in-valve TAVI procedures in patients with a failed bioprosthesis in 2012, this was not a validated treatment option and there was no evidence for the success and long-term efficiency of this procedure.

Recommendations for the choice between a mechanical valve (durability at the cost of bleeding complications) and a bioprosthesis (limited durability but no need for anticoagulation) are based on an age window: “A mechanical prosthesis should be considered in patients aged <60 years for prostheses in the aortic position and <65 years for prostheses in the mitral position (IIb C)”. “A bioprosthesis should be considered in patients aged >65 years for a prosthesis in the aortic position or age >70 years in a mitral position, or those with life expectancy lower than the presumed durability of the bioprosthesis (IIa C)”. We will see that these age windows and paradigms shift in the upcoming revisions of the European and American Guidelines.

The 2014 AHA/ACC Guidelines on valvular heart disease7 did not differ in the recommendations for TAVI: “TAVR is recommended in patients who meet an indication for AVR for AS who have a prohibitive surgical risk and a predicted post-TAVR survival >12 months (IB). TAVR is a reasonable alternative to surgical AVR in patients who meet an indication for AVR and who have high surgical risk (IIa, B)”.

No difference is made between the age window recommendation for mechanical prostheses in the aortic or mitral position (<60 years), and for bioprostheses (>70 years). Individual decision making based on durability, life expectancy, bleeding risk, and patient preference is recommended for patients between 60 and 70 years of age.

The first percutaneous mitral edge-to-edge repair was performed in 2003. The EVEREST I experience was published in 20058, and the randomised controlled trial EVEREST II in 20119. In the 2012 ESC/EACTS Guidelines this experience together with available registry data was considered. Percutaneous treatment of severe primary and secondary MR in inoperable or high-risk patients with a life expectancy of at least one year, as advised by the Heart Team, was given a class IIb (C) recommendation.

The 2014 AHA/ACC Guidelines also saw a class IIb (B) indication for percutaneous edge-to-edge repair in patients with chronic severe primary MR, favourable echo parameters and prohibitive surgical risk. In contrast to the 2012 ESC/EACTS Guidelines, there was no recommendation for percutaneous treatment in secondary MR7.

THE PRESENT

The current set of guidelines includes the completely revised 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease10, and a 2017 focused update on the AHA/ACC Guidelines11. Prior to their publication, the CoreValve High Risk trial12, and two randomised trials comparing TAVI with SAVR in intermediate-risk patients were published13,14. A large clinical experience had also been built up with TAVI, in particular in several European countries and in the USA. The renewed guidelines reinforce the concept of the Heart Team. The decision for treatment, and the choice of treatment should be based largely on a multidisciplinary discussion. The European guidelines introduced and endorsed the concept of Heart Valve Centres of Excellence, which had been outlined by Chambers et al previously15. The main requirements for a centre were a combination of skills in intervention and surgery, advanced imaging modalities, and a Heart Team approach, including outreach to referral centres, as well as an audit process for quality assurance.

The surgical risk score was still used as a criterion to define populations as low-, intermediate- or high-risk. A shift towards use of the logistic EuroSCORE II rather than I was advocated; however, for comparison reasons logistic EuroSCORE I and STS score were used in the recommendations.

SAVR was recommended for patients at low surgical risk (STS score <4%, logistic EuroSCORE >10%) without other risk factors not included in the scores, such as frailty (Class IB).

In patients at increased surgical risk or in the presence of risk factors for surgery not captured by the scores, the decision for TAVI or surgery should be made by the Heart Team. TAVI is recommended in patients not suitable for SAVR as assessed by the Heart Team (IB). A new recommendation was given for the treatment of a failed bioprosthesis. Here, transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation as advised by the Heart Team was introduced as a treatment option (IIa C).

The US focused update mirrored the recommendation for choice of procedure with a Class IA for TAVI in high and intermediate surgical risk and IIa (B-R) in intermediate-risk patients.

When it comes to the choice of surgical prosthesis, the European guidelines did not change and kept the recommendation for a mechanical prosthesis in the aortic position for patients <60 years and for the mitral position for patients <65 years (IIB C). Here the US guidance showed a significant change. The age limit for the recommendation of mechanical valves in either position was lowered by 10 years to <50 years. This is owing to the recognition of percutaneous valve-in-valve implantation as an option for the treatment of patients with failed surgical bioprostheses.

In both guidelines, mitral edge-to-edge repair was considered an option, after careful assessment by the Heart Team in primary mitral regurgitation in patients at high or prohibitive surgical risk and with favourable echocardiographic parameters (IIb C and IIb B). The European guidelines recommend percutaneous repair after evaluation of alternative or complementary treatment options in secondary mitral regurgitation (IIb C). In the US guidelines this treatment did not have an indication for secondary MR in 2017.

THE FUTURE

In the past year we have seen the presentation and publication of four major clinical trials that will impact on the guidelines of the future. The two low-risk TAVI vs SAVR trials, PARTNER 3 and CoreValve Low Risk, complement the previous trial evidence and document the benefit of percutaneous treatment compared to surgery16,17. In the field of mitral regurgitation, the COAPT and MITRA-FR trials shed light on the beneficial role of percutaneous edge-to-edge repair in selected patients with secondary mitral regurgitation18,19.

Ahead of new guidelines, which we expect in Europe for 2021, do we see a paradigm shift as a result of practice and evidence? Also, could this eventually be reflected in the guidelines?

Particularly in the field of aortic stenosis, the new evidence not only stands for the given group of low-risk patients, but rather complements a picture of benefit of one method compared to the other across the spectrum of the population. This becomes clear in a meta-analysis looking at the totality of evidence and documenting the benefits of TAVI across the treated groups of patients20.

TAVI VERSUS SAVR

Do we need to address the question of choice in a completely different way?

TAVI started out as a method that would be chosen if there was no surgical option available. Then it was chosen according to surgical risk. In other words, surgical performance was the default measure and the new technique would fill a gap in patients not selected for surgery.

As evidence accumulates, and experience in everyday clinical practice confirms an early and sustained benefit of transfemoral TAVI in all studied patient populations, should we not eliminate the surgical risk consideration from the decision process? It stands to reason that offering percutaneous treatment to all patients who are technically suitable for TAVI and would be considered for a bioprosthesis is good practice. Patients with intermediate and low surgical risks should be made aware of the alternative treatment options.

ROLE OF THE HEART TEAM

The successful implementation of the Heart Team concept represented a move into multidisciplinary decision making for a subgroup of patients. Depending on the evidence, guidelines and local practice, patients potentially not for surgery were discussed with a view to offering TAVI. Should we not discuss all patients in a multidisciplinary fashion in the future?

With a change of paradigms and clinical practice, the composition and role of the Heart Team in the patient pathway will have to be reviewed and updated.

AGE AND DURABILITY

Considerations for the choice of mechanical surgical valves largely revolve around the age of the patient at presentation, together with assumptions of the risk of a reoperation at the end of the expected durability time window of bioprosthetic valves.

The advent of percutaneous bioprostheses and the options for percutaneous valve-in-valve procedures for failed surgical or percutaneous bioprostheses21 must be taken into account now, and lead to a change in recommendations. Patients should be informed about the new options of low-risk second (potentially third) procedures after initial implantation of a bioprosthesis, avoiding the need for lifelong anticoagulation with the surgical implantation of mechanical valves.

Durability data will accumulate further and, with a consensus on durability criteria, comparisons between systems will become more reliable22. Currently, encouraging long-term observations would suggest that percutaneous systems provide good long-term results well over five years23; longer-term results are awaited. Durability and options for repeat intervention should be seen in the context of age and life expectancy to enable an appropriate choice of first prosthesis in the future.

PATIENT-CENTRED APPROACH

As evident in clinical practice, following TAVI, patients have considerably faster recovery, earlier hospital discharge and better quality of life16. A more patient-centred approach would take patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) and patient-reported experience measures (PREM) into consideration and make these parameters part of the informed choice offered to patients.

MITRAL REPAIR

In the field of secondary mitral regurgitation, the new evidence for edge-to-edge repair requires careful evaluation before translation into clinical practice. This has been the subject of guideline-relevant position statements24. The studies open a new area for interventional treatment, long after this has been the practice in some regions. The complexity of the patient population, the pathophysiology and anatomy require careful selection, and further research is certainly needed to optimise patient selection for maximum treatment benefit in this condition.

Conclusion

Interventional cardiology has seen a wealth of new evidence for percutaneous treatment of aortic stenosis and new insights into the treatment effects of edge-to-edge repair in secondary mitral regurgitation. The cumulative evidence in favour of TAVI suggests a benefit of this procedure in a broad patient population. Clinical practice is changing as a result, and new treatment paradigms are evolving ahead of the next guidelines.

Funding

A. Baumbach is supported by the Barts NIHR Cardiac Biomedical Research Centre.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Baumbach reports institutional research support from Abbott Vascular, consultation and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Sinomed, MicroPort, Abbott Vascular, Cardinal Health, KSH, and Medtronic. S. Windecker reports research and educational grants from Abbott, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, BMS, Bayer, CSL Behring, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, Polares and Sinomed. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.