Abstract

For decades, surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has been the standard treatment for severe aortic stenosis (AS). With the clinical introduction of the concept of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), a rapid development took place and, based on the results of landmark randomised controlled trials, within a few years TAVI became first-line therapy for inoperable patients with severe AS and an alternative to SAVR in operable high-risk patients. Indeed, data from a recent randomised controlled trial suggest that TAVI is superior to SAVR in higher-risk patients with AS. New TAVI devices have been developed to address current limitations, to optimise results further and to minimise complications. First results using these second-generation valves are promising. However, no data from randomised controlled trials assessing TAVI in younger, low-risk patients are yet available. While we await the results of trials addressing these issues (e.g., SURTAVI [NCT01586910] and PARTNER II [NCT01314313]), recent data from TAVI registries suggest that treatment of low-risk patients is already fact and no longer fiction.

Introduction

Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has been the standard treatment for severe aortic stenosis (AS) for decades and is a fast and easy operation with excellent outcomes in a broad patient population1. Minimally invasive surgical techniques have been adopted in recent years to improve postoperative recovery and reduce the likelihood of wound infection, especially in elderly patients2. Improvements in the design of mechanical and bioprosthetic valves have led to a less rigid need for anticoagulation and lower rates of bleeding, thromboembolism and re-operation for bioprosthetic valve failure3-5. As a consequence, 30-day mortality was less than 3% in 20121,6.

With the clinical introduction of the concept of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)7, a rapid development took place, led by the balloon-expandable Cribier-Edwards valve8 (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) and the self-expanding CoreValve®9 (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Within a few years, based on the results of landmark randomised controlled trials10,11, TAVI became first-line therapy for inoperable patients with severe AS and an alternative to SAVR in operable high-risk patients. Indeed, data from a recent randomised controlled trial suggest that TAVI is superior to SAVR in higher-risk patients (one-year mortality 14.2% versus 19.1%12, two-year mortality 22.2% versus 28.6%13, both p=0.04 for superiority).

Evidence against the expansion of TAVI to lower-risk patients

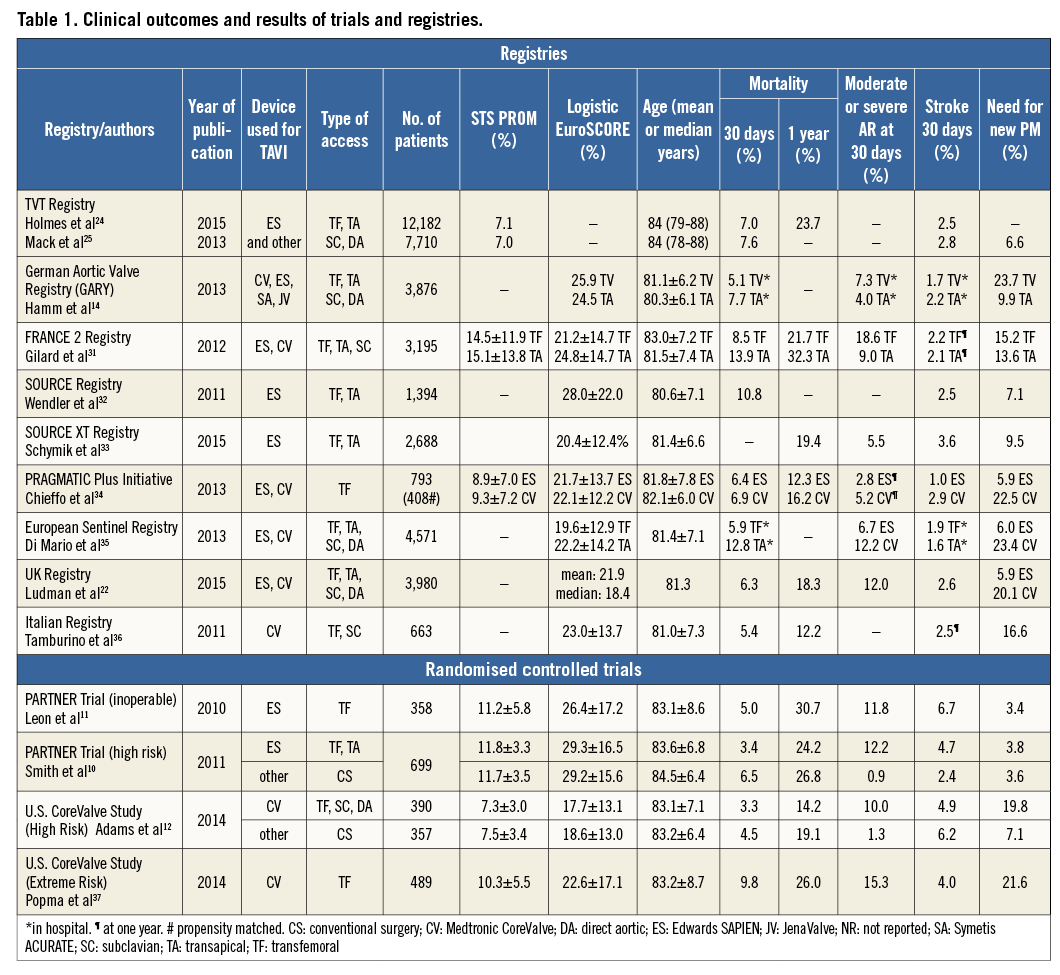

Depending on the device used for TAVI, rates of pacemaker implantation remain high at up to 40% in different studies and registries (Table 1). In contrast, rates of new pacemaker implantation in SAVR patients are lower and only 6% in the German Aortic Valve Registry14.

Stroke after TAVI is another persistent concern. In early studies, stroke rates after TAVI according to VARC-215 definitions were higher compared to surgically treated patients. However, stroke rates after TAVI halved between 2009 and 2013 (Table 1), partially as a result of the decline in the number of patients with multiple comorbidities but also as a consequence of increased operator experience and reduction in procedural duration. Moreover, a recently published small study showed a higher stroke rate (17%) in patients undergoing SAVR than previously reported16. In contrast, low stroke rates (neurologist adjudicated, predominantly ischaemic) of 1.4%, 3.0% and 5.6 % at day 1, day 30 and 2 years, respectively, were reported in a recent multicentre TAVI study17. First studies using cerebral protection devices during TAVI suggest that a further reduction in the rates of new embolic lesions and major strokes is possible18, and optimal regimes of antithrombotic therapy are yet to be defined.

Higher rates of paravalvular aortic regurgitation (AR)6,14 were obtained in heavily calcified valves19 using first-generation TAVI devices and underlined the need for development of new and better transcatheter valves.

Finally, the long-term durability of TAVI procedures needs to be established before expansion of indications to younger and lower-risk patients. In the PARTNER I trial, the five-year risk of death was 71.8% (Cohort B - inoperable patients)20 and 62.4% (Cohort A - high-risk patients)21. In the UK TAVI registry six-year survival was 37.3%22. However, many of these patients were elderly with extensive comorbidities and died of non-cardiac causes. With regard to transcatheter valve failure, only 87 cases were reported between December 2002 and March 2014 (34 prosthetic valve endocarditis, 13 structural valve failure, 15 valve thrombosis, 18 late embolisation, seven valve compression following cardiopulmonary resuscitation)23. However, it remains unclear how many patients with fatal and non-fatal valve dysfunction were unreported in studies and registries. Indeed, the low overall number of long-term survivors makes it almost impossible to come to any conclusion on the long-term durability of transcatheter heart valves at this stage.

Evidence for the expansion of TAVI to lower-risk patients

There is no definitive evidence from randomised controlled trials to support the treatment of low-risk patients using TAVI. In various TAVI registries (Edwards Transcatheter Heart Valve registries, Medtronic CoreValve registries and various multicentre and national registries, Table 1), the mean/median STS score varies between 7.0% and 15.1%. In the TVT registry, the largest available registry, 12.7% of the patients were <75 years and 57.4% had a median STS score <824,25. In the US CoreValve pivotal trial, the mean STS score in the TAVI group was 7.3±3.0%, and most patients (78.2%) had an STS score of 4-10%12. Taken together, these data suggest that younger, intermediate and lower-risk patients are already being treated using TAVI.

In ADVANCE26, a multicentre “real-world” study of more than 1,000 patients undergoing CoreValve implantation, outcomes were separately assessed for low (logistic EuroSCORE <10%) and intermediate-risk patients (logistic EuroSCORE 10-20%): 30-day mortality rates were 2.6% and 4.4%, respectively. This figure for the low-risk group was almost identical to the 30-day mortality (2.4%) of 4,109 SAVR patients in the German Aortic Valve Registry14 where the logistic EuroSCORE was <10% in 80% of patients (median 7.9%). Similarly, the OBSERVANT study compared a propensity-matched population (n=266) of intermediate-risk TAVI and SAVR patients (mean logistic EuroSCORE 9.4±10.4% and 8.8±9.5%, respectively): 30-day mortality was identical (3.8%) in both groups27.

TAVI is still a relatively new technique and many interventionists remain in the learning phase when operator failure can easily drive higher rates of complications. This notion is supported by data from the UK registry where complication rates fell substantially between 2007/2008 and 2012 (mortality 27.2% to 15.5%, stroke 3.6% to 2.4%, pacemaker implantation 29.5% to 5.8%)22, although some of these improvements are likely to relate to improvements in valve design.

Next-generation devices

New second-generation TAVI devices have been developed to address the limitations of earlier technology. For example, low rates of aortic regurgitation (AR), neurological complications (no major stroke) and permanent pacemaker dependency have been demonstrated with the partially recapturable, repositionable and retrievable Portico™ valve (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA)28.

Similarly, there were no cases of moderate or severe paravalvular AR in a study comparing the Lotus™ (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) and SAPIEN 3 (Edwards Lifesciences) valve systems29 – even mild AR was uncommon (Lotus 12%, SAPIEN 3 15%). There were no deaths or strokes and, although rates of new pacemaker implantations were only 4% in the SAPIEN 3 group, they remained high (27%) in patients receiving the Lotus valve29. A study of the Symetis ACURATE™ valve (Symetis, Ecublens, Switzerland) confirmed low rates of paravalvular AR (5% >mild AR) and pacemaker implantation (13%) 30 days post implant30.

Although these preliminary studies of second-generation devices were small with limited numbers of patients20-30, they demonstrate a nearly 100% procedural success rate and clear trends towards lower rates of paravalvular AR, stroke and pacemaker implantation. Larger randomised, multicentre studies are now required to confirm these promising results.

Conclusion

Based upon the available evidence, there is no reason to believe that TAVI in younger and lower-risk patients would be associated with higher short-term mortality than SAVR. However, results from randomised controlled trials specifically evaluating the role of TAVI in younger and lower-risk patients (SURTAVI [NCT01586910], PARTNER II [NCT01314313]) are keenly awaited. Until then, SAVR remains the standard of care for younger low-risk patients with symptomatic severe AS, yielding excellent haemodynamic results and a 30-day mortality rate of <3%. Any decision to favour TAVI over SAVR in this setting should only be made by the Heart Team in conjunction with the patient and should acknowledge the limited data available.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Linke is a consultant to Bard, Medtronic and St. Jude Medical, received grants/research support from Claret Medical Inc. and Medtronic, and honoraria from Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences and Symetis. He is a stock shareholder in Claret Medical Inc. S. Haussig has no conflicts of interest to declare.