During the last decade, several randomised clinical trials have provided an evidence-based paradigm shift from surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) towards transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) for the treatment of patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (AS) at increased surgical risk. Recently, two additional landmark trials comparing TAVI and SAVR in patients at low surgical risk have been published.

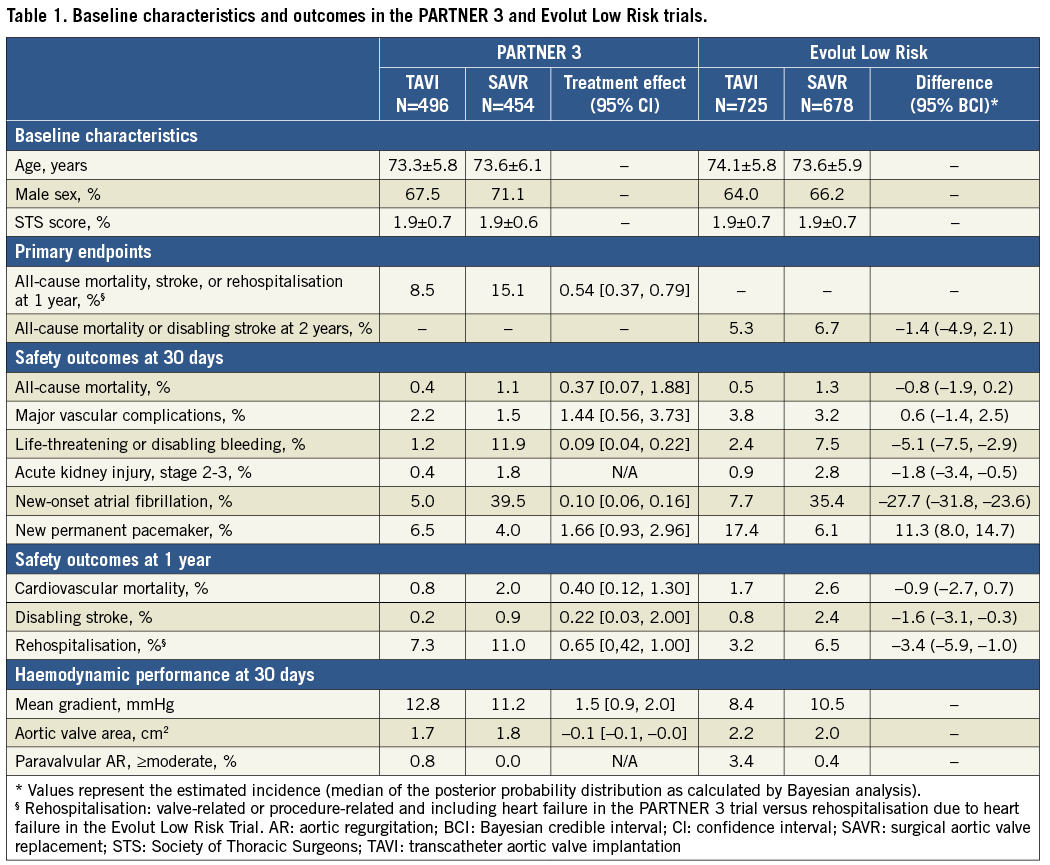

The PARTNER 3 trial, sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences, randomised 1,000 patients with severe AS and at low surgical risk in 71 centres in the USA, Canada, Australia/New Zealand, and Japan to undergo either transfemoral TAVI with the balloon-expandable SAPIEN 3 transcatheter heart valve (THV) (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) or SAVR1. The primary composite endpoint (all-cause death, stroke and rehospitalisation at one year) was significantly lower in TAVI versus SAVR patients (8.5% vs. 15.1%, p<0.001 for non-inferiority; hazard ratio [HR] 0.54, 95% CI: 0.37-0.79, p=0.001 for superiority). At one year, TAVI also resulted in significantly lower rates of stroke, death or stroke, life-threatening or major bleeding, and new-onset atrial fibrillation, whereas there were no statistically significant between-group differences in major vascular complications, new permanent pacemaker (PPM), or moderate or severe paravalvular leak (PVL) (Table 1).

The Medtronic-funded Evolut Low Risk randomised trial compared TAVI using a self-expanding supra-annular THV (CoreValve® 3.6%, Evolut™ R 74.0%, Evolut™ PRO 22.4% [all Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA]) with SAVR in 1,468 patients with severe AS and at low surgical risk in 86 centres in the USA, Australia, Canada, France, Japan, the Netherlands, and New Zealand2. The primary composite endpoint of death from any cause or disabling stroke at 24 months occurred in 5.3% of TAVI recipients and in 6.7% of the surgical group (posterior probability of non-inferiority >0.999). Surgery was associated with higher rates of disabling stroke, bleeding complications, acute kidney injury, and new-onset atrial fibrillation, whereas there was no difference in major vascular complications. On the other hand, TAVI was associated with higher rates of new PPM and moderate or severe PVL (Table 1).

In recent decades, the surgical community has used bioprosthetic aortic valves in younger and younger patients. Patient preference to avoid long-term oral anticoagulation is one reason for the decline in the use of mechanical aortic valve prostheses, rather than an evidence base demonstrating superiority of one valve type over another. Given the propensity of bioprosthetic valves to degenerate, randomised clinical trials comparing TAVI and SAVR in patients with longer life expectancy are of the utmost interest for the community. So, did the two recently published low-risk trials include patients with longer life expectancy? In the PARTNER 3 trial, the mean age was 73.5 years and the average STS score was 1.9%. In the Evolut Low Risk trial, the mean age and STS score were 73.9 years and 1.9%, respectively. As one-year mortality is largely related to the characteristics of the treated patient population, age, frailty and comorbidity drive mortality after the periprocedural period. That these patients truly have longer life expectancy than in earlier TAVI trials is reflected by lower one-year all-cause mortality rates of 1.0% and 2.4% in the two TAVI groups.

In patients with longer life expectancy, PVL and new PPM may be more important issues than in elderly patients. In the PARTNER 3 trial, more than mild PVL at 30 days was found in 0.8% and 0.0% in the TAVI and SAVR groups, respectively, whereas the corresponding numbers were 3.4% and 0.4% in the Evolut Low Risk trial. While the proportion of patients with moderate PVL after TAVI is similar to surgery, TAVI is still associated with a significantly higher rate of mild PVL compared to SAVR: 28.7% versus 2.9% in PARTNER 3 and 36.0% versus 3.0% in Evolut Low Risk. The impact of mild PVL on left ventricular function, symptoms, and long-term mortality in patients with longer life expectancy is still unknown.

The higher rate of conduction abnormalities and requirement for PPM after TAVI as compared to SAVR may also impact on long-term outcomes for younger AS patients since right ventricular pacing is considered to be harmful4. It is well known that the rate of conduction abnormalities is related to the type of THV prosthesis used. Thus, the rate of new PPM at 30 days was 6.6% for balloon-expandable THV in PARTNER 3 and was not statistically different from the surgical group (4.1%). On the other hand, the new PPM rate for the self-expanding THV in Evolut Low Risk was 17.4% and was significantly higher than after SAVR (6.1%). Hence, the risk of conduction abnormalities should be considered when choosing a THV prosthesis for patients with longer life expectancy.

The durability of bioprosthetic aortic valves is another important aspect to consider. To date, with mainly elderly patients treated with TAVI, the longevity of THV is likely to exceed the patient’s life expectancy. However, patients with longer life expectancy may survive one or more bioprosthetic aortic valves. Little is known about long-term durability of THV prostheses, but six-year data from the NOTION trial showed that the rate of structural valve deterioration was lower and the rate of valve failure was similar for the Medtronic self-expanding THV compared to surgical bioprosthetic valves4. In the Evolut Low Risk trial, the mean aortic valve area was 2.2 cm2 after TAVI and 2.0 cm2 after SAVR, whereas in PARTNER 3 the corresponding values were 1.7 cm2 and 1.8 cm2. Balloon-expandable THV thus provided smaller aortic valve area compared to self-expanding THV and surgical bioprostheses. The rates of severe prosthesis-patient mismatch, which has been associated with long-term mortality and symptom resolution, was therefore more common with balloon-expandable (8.3%) compared to self-expanding (1.8%) valves. A larger effective orifice area may also translate to a lower rate of structural valve deterioration and hence be another important factor when choosing a THV for patients with longer life expectancy.

Aortic stenosis in younger patients is often related to bicuspid aortic valve morphology. Although TAVI in bicuspid AS has been associated with less favourable outcomes than in tricuspid aortic valves5, better understanding of valve sizing, optimal implantation technique, and next-generation THV prostheses have led to improved results. However, TAVI in bicuspid aortic valves is currently only used in patients at high surgical risk. Since patients with bicuspid aortic valves were excluded from the two low-risk trials, there is still no evidence to support TAVI in patients with bicuspid aortic valves and at low surgical risk. Dedicated trials comparing TAVI and SAVR in patients with bicuspid aortic stenosis are required.

The PARTNER 3 trial and the Evolut Low Risk trial provide important evidence for expanding TAVI as an alternative to SAVR in patients at low surgical risk. The two trials not only demonstrated that TAVI is associated with lower rates of stroke and mortality than SAVR, but also that the previously higher rates of PVL, PPM and major vascular complications after TAVI have declined to levels similar to those found after SAVR. These two well-conducted trials are expected to provide a paradigm shift in the treatment of patients with AS and at low surgical risk. The next logical step could be to explore TAVI versus SAVR in younger patients since, in the two low-risk trials, the mean age was around 74 years; however, surgical bioprostheses are often used in patients ≤60 years. Furthermore, the outcome of TAVI in younger patients with bicuspid aortic valves also needs to be evaluated against SAVR. Currently, one trial, NOTION-2 (NCT02825134), is addressing these issues.

Conflict of interest statement

L. Søndergaard has received consultant fees and institutional research grants from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. D. Mylotte is a consultant for Medtronic, Boston Scientific and MicroPort. O. De Backer has no conflicts of interest to declare.