Abstract

Aims: The occurrence of type I endoleaks represent an ominous sign after endovascular aneurysms repair (EVAR). We report our experience using balloon-expandable stents (BES) for the treatment of proximal Type I endoleaks at five high-volume hospitals in Argentina.

Methods and results: Of 1,395 patients who underwent EVAR, we retrospectively collected data of 29 (2%) consecutive patients who underwent additional BES to repair proximal type I endoleaks. The mean age was 75.8 years old (range 63-87) and 93% were male. A hostile anatomy was found in 89.6% of the cases. BES oversize (balloon/neck diameter ration ≥30%) was frequent (69%); whereas, BES/prosthesis diameter ratio was less than 1 in 79% of the cases. Complete and partial sealing was obtained 72 and 28% of the cases, respectively. There were no immediate or late surgical conversion or major complications related with stent implantation. At a median time follow-up of 14.9 months (25-75% interquartiles: 4.5-17.5 months), there were no cardiovascular deaths, evidence of aneurysm sac enlargement or need for re-intervention.

Conclusions: Our preliminary results suggest that BES implantation for the treatment of proximal type I endoleaks is feasible and safe with favourable mid-term results and may preclude the need for surgical conversion.

Introduction

Endovascular aortic abdominal aneurysm repair (EVAR) has become a valuable alternative to open surgery1,2. Although EVAR is associated with lower operative morbidity and mortality than open repair, late survival is not improved by EVAR3. Certainly, this rise in late mortality with EVAR is chiefly due to the occurrence of late graft/aortic sac rupture, a catastrophic event that appears to be strongly dependant on graft failure and/or the development of various types of endoleaks4-6. In particular, type I endoleaks occur when a persistent channel of blood flow develops due to inadequate seal at the graft ends. Type I endoleaks bear a considerable risk of future rupture and usually require some type of intervention including: balloon remodelling of the prosthesis attachment, placement of cuff at the proximal neck or distal landing areas of the graft7,8. Most of the times, these are effective ways of controlling the endoleaks. In refractory cases of proximal type I endoleaks, placement of a giant balloon-expandable stent (BES) to enhance graft radial force and improve graft artery wall apposition is advisable9-11, however, clinical evidence supporting is currently lacking. Therefore, the aim of our study is to report our experience with BES implantation for the treatment of proximal type I endoleaks following EVAR.

Methods

We collected data from five high-volume hospitals in Argentina. All EVAR patients who had postprocedural type I endoleaks and underwent BES implantation for graft sealing were included in this study. Retrospective anatomic and procedural data potentially linked with type I endoleaks was gathered in all patients. Endoleaks were detected during the procedure by angiography and later confirmed with computed tomography. Complete sealing was defined as the absence of leak after stenting, confirmed afterwards by 30-day computer tomography (CT). Partial sealing was defined as a minimal leak after stenting that was not confirmed by 30-day CT.

Procedure

Twenty-two patients underwent BES implantation immediately after EVAR (during the same procedure). In seven patients, postprocedural CT confirmed type I endoleak and a BES was placed as a separate procedure.

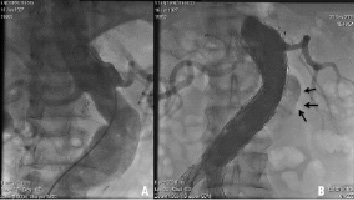

All procedures were performed in the cardiovascular catheterisation laboratory. Usually, postprocedural detection of proximal type I endoleaks prompted dilation with a valvuloplasty balloon (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A. Pre-EVAR images showing a short angulated neck. B. Intra-operative angiography demonstrated a proximal Type I endoleak (arrows).

If the endoleak still persisted, a decision to further undergo BES implantation was made.

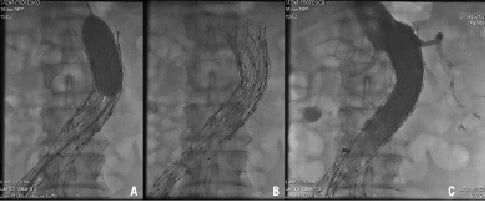

We used the same guidewire that was used during EVAR, an extremely stiff 0.035-inch guidewire (Lunderquist; Numed, Hopkinton, NY, USA; 260 cm in length, with a soft and flexible tip at its distal end, which was 4 cm in length) that was kept across the graft and parked at the thoracic descending aorta. Through this guidewire, a long sheath (16 Fr to 20 Fr) was then positioned beyond the delivery zone. Prior to deployment, a giant bare metal stent was mounted over a 30x40-50 mm valvuloplasty balloon. This BES was subsequently placed into the sheath and delivered to the target area under fluoroscopy. The BES was deployed across the renal arteries, partially covering the bare and the covered proximal segments of the graft. To deploy, the sheath was fully retracted in order to uncover the stent and inflation was performed to achieve full stent expansion and apposition, after that, the balloon was withdrawn and a final digital angiogram was performed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A. BES deployment at the level of the renal arteries. B. Angiographic image showing adequate BES expansion. C. Complete exclusion of the aneurysm.

If required after deployment, further overexpansion can be gained using the valvuloplasty balloon.

Follow-up imaging

All patients underwent clinical and CT scan follow-up at one, six and twelve months and thereafter, annually.

Results

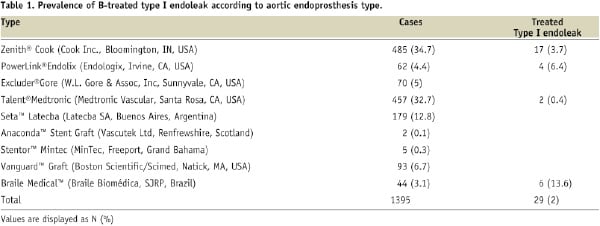

A total of 1,395 patients underwent EVAR and 50 patients (3.6%) had a type I proximal endoleak, 29 out of 50 underwent additional BES implantation (Table 1).

Mean patient age was 75.8 (63-87) and 93.1% were males.

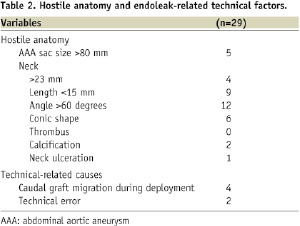

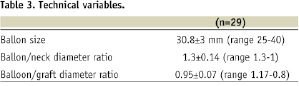

Anatomical and procedural characteristics are reported in the Tables 2 and 3.

In our study population, the presence of anatomical predictors of type I endoleaks was frequently encountered (26/29, 89.6%, Table 2): large neck (13.8%), short neck (31%), severe neck angulation (41.3%), conic neck shape (20.7%) and large aortic sac (17.2%). BES implantation was performed during the index procedure in 22 cases and deferred in seven. Various BES types were used as follows: a) bare stents: 23 Palmaz Genesis XL (Cordis Co, Miami, FL, USA) and 2 Andrastent XXL (Andramed GMBH, Reutlingen, Germany), b) Dacron covered Stent-graft: 4 SACBI (Latecba SA, Buenos Aires, Argentina). BES oversize (balloon/neck diameter ration ≥30%) was frequent (69%); whereas, BES/prosthesis diameter ratio was less than 1 in 79% of the cases (Table 3). Complete and partial sealing was obtained 72 and 28% of the cases, respectively. There were no immediate or late surgical conversion or major complications related with stent implantation. At a median time follow-up of 14.9 months (25-75% interquartiles: 4.5-17.5 months), there were no cardiovascular deaths, evidence of aneurysm sac enlargement or need for re-intervention. By preprocedural CT scan examination, AAA diameter was 74±21 mm. At follow-up (median 14.9 months), no endoleaks were observed and AAA sac diameter was 68±24 mm. There were no renal arteries occlusions at index procedure and no patient had renal failure at follow-up.

Discussion

Type I endoleaks occur mainly due to inadequate seal of graft ends. There are several anatomical factors that contribute to its development such as a short neck (<15 mm), a large diameter neck (≥32 mm), tapered necks, increased angulations (>60%), the presence of thrombus and calcification and a non-circular landing zone12-14. In general, proximal stent graft oversize (15–20%) and landing close to the renal arteries may prevent an incomplete seal. In addition, grafts that require a significant radial force in order to achieve adequate fixation are particularly prone to distal migration and, consequently type I endoleaks15. Second and third generations endografts have been designed with proximal anchors and have been successful in preventing caudal migration and type I endoleaks16.

Although the occurrence of type I endoleaks is a fairly infrequent phenomenon (4.2%)7, it represents an ominous complication following EVAR and some form of intervention is clearly indicated. Several measures such as additional balloon dilation or placement of extender cuff usually close the leak, but their effect may not be long-lasting. The latter may be due to the presence of thrombus at the proximal neck which may eventually dissolve provoking graft migration or incomplete sealing later on. In order to permanently seal the leak, forceful implantation of a giant BES may be the best option. However, scant data is currently available regarding this technique9,10. In the present study, additional BES placement at the proximal attachment site for the treatment of type I endoleaks was found feasible, safe and fairly effective without long-term recurrence at 14.9 months follow-up. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest series reporting endovascular repair of proximal type I endoleaks with giant BES. Even though several authors advocate surgical conversion for refractory cases of proximal type I endoleaks, additional BES implantation emerges as a likely alternative since it is a rather straight-forward technique and less invasive than surgical conversion, potentially resulting into lower morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Our preliminary results suggest that transrenal BES implantation for the treatment of proximal type I endoleaks is feasible and safe with favourable mid-term results and may preclude the need for surgical conversion. The actual role of this minimally invasive strategy should be further investigated.