Abstract

Aims: Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blocking agents seem to improve percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) results in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). We aimed to compare the effect of pre-hospital administration of tirofiban in STEMI patients with and without diabetes mellitus (DM) treated with primary PCI.

Methods and results: We performed a pre-specified sub-analysis of the randomised On-Time II trial (n=984) and it’s open label run-in phase (n=414), which investigated pre-hospital administration of high dose tirofiban in STEMI patients treated with primary PCI. Two-hundred and twenty (16%) diabetic patients (known DM or Hba1C ≥6.2%) were included, 101 in the placebo group and 119 in the tirofiban group. In patients with DM, randomisation to tirofiban resulted in a lower residual ST deviation (5.1±8.5 mm vs. 6.2±5.6 mm, p=0.003), a reduced infarct size (CK 1694±1925 U/L vs. CK 2040±1829 U/L, p=0.02) and a trend towards lower one-year mortality (4.6% vs. 11.6%, p=0.07). The beneficial effects of tirofiban were more pronounced in diabetic patients compared to patients without diabetes.

Conclusions: Pre-hospital administration of tirofiban in diabetic STEMI patients treated with primary PCI improves ST resolution and reduces myocardial infarct size. Tirofiban seems particularly beneficial in patients with diabetes.

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as reperfusion therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is superior to thrombolysis1. Pre-hospital diagnosis of STEMI might further contribute to improving prognosis by enabling administration of pharmaceutical agents during transportation to the PCI centre2. Currently, pre-treatment generally consists of aspirin, clopidogrel and heparin. Studies have produced conflicting results, and the results of a meta-analysis of these studies suggest that early co-administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade in adequate dosage in these patients may improve angiographic and clinical outcome3. Prognosis of STEMI patients in general has improved dramatically with the implementation of modern reperfusion strategies. Patients with diabetes, however, remain a high-risk group with increased short- and long-term mortality4,5. Sub-optimal angiographic results and prothrombotic properties of platelets in diabetes and hyperglycaemia may be partly responsible for this poor prognosis. So far, there are few data on the effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade in diabetic patients with STEMI treated with primary PCI6. We performed a pre-specified sub-analysis of the On-Time 2 trial, investigating angiographic and clinical outcome of the diabetic patient population with STEMI randomised to early administration of high dose tirofiban or placebo during transportation to the PCI centre7.

Methods

The Ongoing Tirofiban in Myocardial Evaluation (On-TIME) 2 trial was a prospective, multicentre, placebo-controlled, randomised, clinical trial. The study consisted of two phases: an open label run-in phase (phase 1) and a placebo controlled double-blind phase (phase 2). The rationale, design and primary results of the study have been described previously7. Study enrolment was from June 2004 to Nov 2007, at 24 participating centres in three countries (The Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium). The study population consisted of STEMI patients who were candidates to undergo primary PCI. Eligible patients were men and women aged 21-85 years with symptoms of acute myocardial infarction of more than 30 minutes but less than 24 hours, and ST-segment elevation of more than 1 mV in two adjacent ECG leads. Exclusion criteria were known severe renal dysfunction, therapy resistant cardiogenic shock, persistent severe hypertension, or a contraindication to anticoagulation or increased risk of bleeding. Informed consent was obtained in the ambulance or referring hospital.

Procedures

Patients were randomly assigned to pre-hospital treatment with tirofiban (25 µg/kg bolus and 0·15 µg/kg/min maintenance infusion for 18 hours) or placebo (bolus plus infusion) by blinded sealed kits with the study drug. All staff and study personnel were blinded to the treatment. In the ambulance or referring centre, all patients also received a bolus of 5000 IU of unfractionated heparin intravenously together with aspirin 500 mg intravenously and a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel orally. Before PCI, additional unfractionated heparin was only given if the activated clotting time was less than 200 seconds. Coronary angiography and PCI were done according to each institution’s guidelines and standards. Before, during, or after PCI, bail-out tirofiban could be given at the physicians discretion and for pre-defined indications. The primary efficacy endpoint for the On-Time II study as well as for the current sub-analysis was the extent of residual ST-segment deviation at one hour after PCI, as previously described8. The sum of ST-segment deviation in all 12 leads was measured 20 ms after the end of the QRS complex with a calliper. The key secondary endpoints were initial TIMI flow of the infarct related vessel and enzymatic infarct size. Other endpoints were the composite of death, recurrent myocardial infarction and urgent target vessel revascularisation (TVR) at 30 days and all cause death at one year follow-up. Acute stent thrombosis was defined as occurring within 24 hours after PCI. Myocardial infarct size was defined as mean peak creatine kinase during the index myocardial infarction. The safety endpoints of interest included the rates of haemorrhage, transfusions, stroke, thrombocytopenia and serious adverse events. Bleeding was assessed with the TIMI criteria9. Mortality status was also assessed at one-year.

For the current analysis, patients included in the On-Time 2 study were combined with patients included in the On-Time 2 open-label study, as described previously7.

Diabetes was defined as the presence of diabetes on admission. Patients with a Hba1C level of ≥6.2% were also considered to be diabetic. Diagnosis of diabetes during admission was not recorded.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed according to the intention to treat principle. All p values were two-sided. For all analyses, statistical significance was assumed when the two-tailed probability value was <0.05. Continuous data were expressed as mean±standard deviation and categorical data as percentage, unless otherwise denoted. The analysis of variance and the chi-square test were appropriately used for continuous and categorical variables respectively. The χ2 test for trend was used to analyse the percentages of patients in each of the four groups of residual ST-segment deviation and TIMI flow pre-PCI. Multivariate analyses were performed to identify independent predictors of adverse outcome.

Results

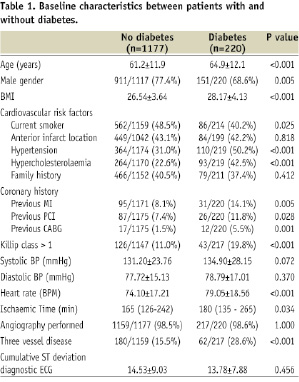

The total number of included patients was 1,398, of which 984 were included in the On-Time 2 study and 414 in the On-Time 2 open-label study. Of the 1,398 patients, 220 had diabetes (16%), of which 156 patients (11.1%) with known diabetes and 64 (4.6%) with a Hba1C level ≥6.2%. Baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1.

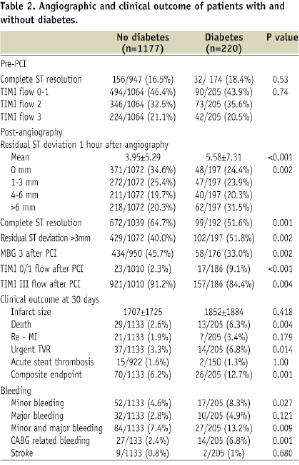

Patients with diabetes had a baseline profile with more high-risk features. In Table 2 clinical and angiographic outcome is shown.

Patients with diabetes had a significant worse clinical and angiographic outcome. The primary endpoint of residual ST deviation one hour after PCI was 4.0±5.2 mm in patients without DM vs. 6.4±8.4 mm in patients with DM (p<0.001). TIMI III flow post-PCI and myocardial blush grade were significantly reduced in patients with diabetes. Patients with diabetes had a significantly higher mortality as well as a higher incidence of the composite endpoint of death, re-MI and urgent TVR. After multivariate analysis (including age, gender, previous MI, previous PCI, previous CABG, Killip class, 3-VD, smoking, hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension) diabetes was a strong independent predictor for the composite endpoint of death, re-MI, urgent TVR and PCI failure (OR 2.6, 95%CI: 1.5-4.9, p=0.002). Diabetes was associated with a significant increase in bleeding, which was in part related to CABG. Also after one-year mortality in patients with diabetes was significantly higher compared to patients without diabetes (7.9% vs. 4.2%, p=0.023).

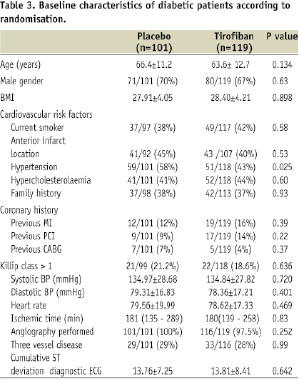

Of the 220 patients with diabetes, 101 were randomised to placebo and 119 patients were randomised to tirofiban. Baseline characteristics of these patient groups are listed in Table 3.

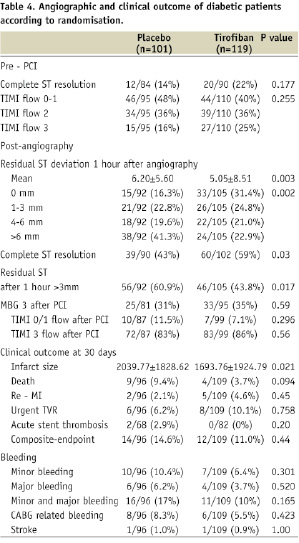

Angiographic and clinical outcome measures are listed in Table 4.

Pre-treatment with tirofiban resulted in a significant improvement in the primary endpoint of residual ST resolution. Total myocardial infarct size was significantly reduced in diabetic patients treated with tirofiban. After one year, there was a strong trend towards a lower mortality in diabetic patients treated with tirofiban compared to diabetic patients treated with placebo (4.6% vs. 11.6%, p=0.07).

Effects of tirofiban in diabetes compared to non-diabetes

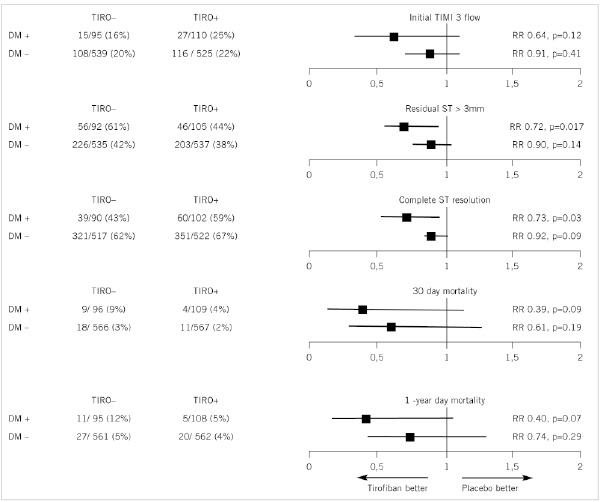

The effect of tirofiban on degree of ST resolution one hour after PCI, initial TIMI III flow and mortality is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The effect of tirofiban on outcome (relative risk) in patients with and without diabetes mellitus.

In patients with diabetes, tirofiban pre-treatment resulted in a higher rate of complete ST resolution and a lower prevalence of residual ST deviation >3 mm. In patients without diabetes, the improvement of ST resolution by tirofiban was not significant. In patients with diabetes, tirofiban led to a significant reduction in infarct size (CK 1694±1925 vs. 2040±1829, p=0.02) whereas this effect of tirofiban was not observed in patient without diabetes (CK 1660±1623 vs. 1753±1822, p=0.68).

In patients with diabetes, tirofiban compared to placebo was not associated with an increase in bleeding (10.1% vs. 16.7%, p=0.16) but in patients without diabetes tirofiban resulted in an increase in bleeding (9.2% vs. 5.7%, p=0.024). Two diabetic patients, one in each treatment group suffered from a stroke. In patients without diabetes, there were eight strokes (1.4%) in the placebo group and one stroke in the tirofiban group (0.2%) (p=0.02).

Conclusions

Our study showed that diabetic patients with STEMI had an adverse clinical and angiographic outcome compared to patients without diabetes. Interestingly, pre-hospital administration of high-dose tirofiban in diabetic patients with STEMI was associated with a significant improvement in residual ST deviation and a substantial reduction in mean infarct size as well as a strong trend towards lower one-year mortality. These beneficial effects of tirofiban were more pronounced in the patient group with diabetes compared to patients without diabetes. Pre-hospital treatment of tirofiban may help to improve prognosis in this group of patients.

Diabetic patients with an acute coronary syndrome are a well known high risk group and their adverse prognosis has been well recognised10. Part of their adverse outcome is attributable to their higher baseline risk features, such as higher age and higher prevalence of vascular comorbidity11. However, part of this adverse outcome may be due to suboptimal PCI results. In our study, both epicardial as well as myocardial perfusion success, assessed by myocardial blush grade and ST resolution, was lower in patients with diabetes. These findings are in line with previous reports12,13. Part of this association may be due to more complex lesions and more diffuse coronary artery disease in these patients14. Furthermore, platelet function in diabetes is disturbed in heterogeneous and complex ways15,16. This diabetic thrombocytopathy may also play a role in the higher rate of observed poor myocardial reperfusion. Interestingly, various studies report a beneficial effect of abciximab with regard to myocardial perfusion after primary angioplasty, however patient numbers in these studies were limited and no specific data with regard to patients with diabetes were given17-19.

The On-Time 2 study already showed a beneficial effect of pre-hospital administration of high dose tirofiban on residual ST resolution in the general patient population7. Furthermore, a significant reduction in major cardiac events in the pooled analysis of the On-Time 2 and On-Time open-label study was reported (ten Berg et al, JACC June 2010, in press). In the current analysis, including a large number of diabetic patients, the effect of tirofiban on angiographic outcome was compared to their non-diabetic counterparts. We found that the absolute effect of tirofiban on ST resolution, initial TIMI III flow and myocardial infarct size appeared larger in patients with diabetes compared to patients without diabetes. This potential drug interaction with diabetes was also suggested previously by Montalescot in a meta-analysis of the ISAR II, ACE and the ADMIRAL trial6. In this meta-analysis, investigating abciximab in STEMI patients treated with primary PCI, a significant reduction in mortality and re-MI after three years was observed in diabetic patients, whereas only a trend was found in non-diabetics.

An explanation for these findings could be limited inhibition of platelets by standard pre-treatment of STEMI patients, which generally consists of aspirin, clopidogrel and heparin. Indeed, high platelet activity is more frequent in patients with type 2 diabetes as compared with non-diabetic patients, also in the setting of dual antiplatelet therapy16,20,21. Suboptimal inhibition of platelets at the time of PCI is correlated with a higher rate of adverse events after the procedure22. Therefore the additional antiplatelet effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockers is more pronounced in patients with diabetes, translating into a larger clinical outcome effect.

Since our study was not powered to detect differences in clinical outcome and follow-up duration was relatively short, no significant effect of tirofiban on clinical outcome could be demonstrated. However, both initial TIMI III flow as well as the degree of ST resolution after primary PCI are strongly associated with preservation of left ventricular systolic function and improved prognosis23,24. Indeed, there was a strong trend towards a lower one-year mortality in diabetic patients treated with pre-hospital tirofiban as compared to those treated with placebo. So the angiographic and electrocardiographic benefits seen with tirofiban in our population seem to be reflected in improved clinical outcome.

Our study shows that particularly diabetic patients with STEMI seem to benefit from early initiation of high-dose tirofiban. Excess bleeding, reducing the net beneficial effect, is a potential drawback for the use of these agents on top of other antiplatelet agents. This may particularly apply to patients with diabetes, as diabetes itself proved to be a risk factor for bleeding. Interestingly, the use of high dose tirofiban in this patient group did not result in an increase in minor or major bleeding, nor in increased occurrence of stroke. So, despite the fact that patients with diabetes tend to have more bleeding complications, this increase in bleeding does not seem to be under the influence of additional antiplatelet medication. This finding is in line with the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial which investigated the effect of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with an acute coronary syndrome planned for PCI. In patients without diabetes, there was an increase in major bleed with the use of prasugrel, whereas no increase in bleed was seen in diabetic patients25.

Limitations

This article concerns a prespecified sub-analysis with limited patient numbers. Surrogate endpoints were used as outcome measures between the two patient groups, as dictated by the limited patient numbers with diabetes. However, the endpoints used correlate well with eventual outcome. Hba1C levels lack the diagnostic accuracy of an oral glucose tolerance test or fasting glucose level to detect diabetes. Unfortunately, these latter tests were not performed on a routine basis in our study. However, Hba1C levels were routinely measured on admission and elevated Hba1C levels do correctly detect diabetes in a substantial part of patients and are a well established marker for long-standing glucose deregulation26,27. This is of particular importance since it has been well established that a substantial number of patients presenting with myocardial infarction have previously undiagnosed diabetes28. Irrespective of diabetic status, patients with Hba1C levels ≥6.2 can be considered patients with a high metabolic risk.

Acknowledgements

J.R. Timmer was the principal author of the current manuscript and contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. A.W.J. van ‘t Hof, J.M. ten Berg and C. Hamm initiated and designed the On-Time 2 trial and revised the intellectual content. A.A.C.M. Heestermans contributed to the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data and performed critical writing. J.W. van Werkum contributed to critical writing and revising the intellectual content. T. Dill, J.H.E. Dambrink, H. Suryapranata and J.P. Ottervanger contributed to revising the intellectual content.