Abstract

Aims: To investigate the effects of clopidogrel and eptifibatide on platelet reactivity in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and hypothermia.

Methods and results: VerifyNow® and Multiplate® aggregometry were used before, and 4, 12, 22 and 48 hours after 600 mg clopidogrel treatment in 28 post-cardiac arrest hypothermic patients and in 14 normothermic patients with acute coronary syndrome. Basal platelet reactivity after stimulation with iso-thrombin receptor-activating peptide (TRAP) and PAR4-activating peptide (BASE) was significantly lower in the post-cardiac arrest group and persisted up to 48 hours. The antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel measured by VerifyNow and expressed as % inhibition was significantly lower in the post-cardiac arrest group. It was close to zero with an increase to only around 10% after 48 hours. Post-cardiac arrest patients receiving eptifibatide showed profound platelet inhibition measured by both VerifyNow IIb/IIIa and Multiplate TRAP tests for at least 22 hours after administration.

Conclusions: Post-resuscitation syndrome with ongoing hypothermia is associated with decreased platelet reactivity. Clopidogrel loading does not significantly affect platelet function during the first 48 hours. This is in contrast with eptifibatide which produces profound platelet inhibition, and may be used to bridge insufficient inhibition by clopidogrel.

Introduction

Since an acute coronary event is the main trigger of sudden cardiac arrest, an increasing number of resuscitated patients nowadays undergo immediate coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)1,2. PCI and stenting are obviously associated with the need for antiplatelet treatment including acetylsalicylic acid, P2Y12 inhibitors and platelet glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitors. In up to 20% of patients who regain consciousness after reestablishment of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), oral administration of acetylsalicylic acid and P2Y12 inhibitors can be accomplished easily. Unfortunately, the majority of patients are comatose despite ROSC and therefore remain intubated and mechanically ventilated3. Moreover, hypothermia is induced and maintained between 32 and 34°C for up to 24 hours to reduce post-resuscitation brain injury4-6. While acetylsalicylic acid and GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors can be administered intravenously, P2Y12 inhibitors are currently available only as tablets. Administration of crushed and dissolved tablets via a nasogastric tube therefore remains the only option. We hypothesised that such administration, post-resuscitation syndrome and ongoing hypothermia may adversely affect P2Y12 absorption and metabolism, resulting in a delayed onset of action7. We also addressed the role of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in these settings.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted at the University Medical Centre Ljubljana from August 2011 to May 2013. The protocol was approved by the Slovenian National Ethics Committee (112/05/11). Informed consent in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest was obtained from the closest relatives. Informed consent in the control group of conscious normothermic patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and without cardiac arrest was obtained before PCI.

The post-cardiac arrest group included consecutive comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with suspected ACS who underwent immediate coronary angiography, PCI and hypothermia. Periprocedural antiplatelet treatment included an intravenous bolus of 250-500 mg acetylsalicylic acid (Aspegic®; Sanofi, Paris, France) and 600 mg of clopidogrel (Plavix®; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA) crushed, dissolved in water and injected through a nasogastric tube. This was followed by a daily dose of 100 mg acetylsalicylic acid and 75 mg of clopidogrel. Eptifibatide (Integrilin®: GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, Middlesex, UK) was used at the discretion of the interventional cardiologist and was administered as two intravenous boluses (180 µg/kg) within ten minutes, followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 2 µg/kg/min for up to 12 hours. Periprocedural and intensive care treatment was performed as previously reported8,9. In short, the patients were cooled to between 32 and 34°C for 24 hours. Core temperature was measured by a urine thermo catheter. Sedatives, analgesics and neuromuscular blocking agents were used during hypothermia to suppress shivering. After 24 hours of hypothermia, slow spontaneous rewarming was allowed.

The control group consisted of patients with ACS (STEMI or NSTEMI) without preceding cardiac arrest who underwent coronary angiography and PCI under normothermia. They received the same periprocedural antiplatelet treatment except that they were already on acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin®; Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany) and clopidogrel tablets were normally swallowed. Other procedures were in accordance with the international guidelines and our clinical routine10.

Exclusion criteria were thrombocytopaenia (<50×109/L), known allergic reaction to antiplatelet agents and known deficit in platelet function. Patients receiving any P2Y12 inhibitor before enrolment were also excluded.

Blood samples were collected on admission and 4, 12, 22 and 48 hours after clopidogrel administration. Blood was collected in two vacuum tubes containing 0.11 M sodium citrate and one vacuum tube containing lithium heparin (Vacutube; Laboratorijska tehnika Burnik, Vodice, Slovenia). Platelet function was measured in whole blood by VerifyNow® (Accumetrics, San Diego, CA, USA), and by Multiplate® (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd, Rotkreuz, Switzerland).

The VerifyNow P2Y12 assay (Accumetrics) measured adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-induced agglutination of platelets to fibrinogen-coated beads. The presence of prostaglandin E1 makes the test specific for the P2Y12 receptor pathway. The measured change in light transmittance is reported as a “P2Y12 receptor blockade” and expressed as P2Y12 reaction units (PRU). In addition, the device calculates the percentage of P2Y12 inhibition, based on iso-TRAP and PAR4-activating peptide-induced platelet aggregation which provides “basal platelet reactivity” (BASE) also reported in PRU. BASE should be independent of P2Y12 receptor, although it may be slightly reduced under treatment by thienopyridines11. From “P2Y12 receptor blockade” and BASE, the % inhibition can be calculated as (1–[P2Y12 receptor blockade/BASE]×100). The VerifyNow IIb/IIIa assay utilises iso-TRAP for maximal activation of platelets which agglutinate to fibrin-coated beads. The measured change in light transmittance is reported as platelet aggregation units (PAU). Temperature was automatically set to 37°C during VerifyNow assay. VerifyNow IIb/IIIa measurement was performed within 20 minutes and all other measurements within one hour from blood collection.

Platelet impedance aggregometry was measured with Multiplate. The effect of clopidogrel was assessed with the ADP test, in which platelet adhesion and aggregation was induced with ADP. The effect of eptifibatide was assessed with the TRAP test which measures platelet adhesion and aggregation induced with iso-TRAP. The increase of impedance by the attachment of platelets onto the sensor wires was transformed to arbitrary aggregation units (AU) and plotted against time. The area under the aggregation curve was calculated and expressed as units (1 U corresponds to 10 AU*min). The temperature of the Multiplate device was set to be equal to the patient’s temperature in the hypothermic patients and to 37°C by default in the normothermic patients. All measurements were performed within one hour from blood collection.

Coronary angiograms were examined and angiographic features were determined. Survival, neurological outcome in terms of the cerebral performance category scale, and major adverse cardiac events including stent thrombosis were followed until hospital discharge12.

Statistical analysis was performed by using the Statistica 8.0 package (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Distribution of variables was tested by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed data are expressed as means and standard deviations, while skewed data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges. Differences between the groups were analysed by the χ2 test (categorical variables), Student’s t-test (continuous variables with normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (continuous variables with skewed distribution). For comparison of numerical variables within the group, ANOVA repeated measurement was used. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Among 62 consecutive comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with suspected ACS undergoing immediate coronary angiography, PCI and hypothermia, 28 patients were included. Reasons for exclusion were logistic problems (n=16), P2Y12 inhibitor pretreatment (n=16), delay in administration of acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel after PCI (n=1), and death in the cathlab (n=1). The control group included 14 patients with ACS who did not receive any P2Y12 inhibitor pretreatment.

Except for younger age in the control group, there was no difference in terms of gender, risk factors for coronary artery disease, incidence of STEMI/NSTEMI and cardiac troponin concentrations (Table 1). Platelet count was 241±107×109/L in the post-cardiac arrest group and 202±33×109/L in the control group (p=0.20). Both groups were comparable in the extent of coronary artery disease, presence of acute culprit lesion and initial TIMI flow (Table 2). There was no difference in the utilisation of periprocedural eptifibatide, stenting, angiographic success of PCI and stent thrombosis during the hospital stay. Survival to hospital discharge with good neurological outcome was 43% in the post-cardiac arrest group and 86% in the control group (p=0.02).

Because cooling had been started before arrival at the cathlab, the core temperature in the post-cardiac arrest group on admission was 34.5±1.1°C. It further decreased to 33.0±0.9°C at four hours, to 32.6±0.6°C at 12 hours, and to 33.0±0.5°C at 22 hours. Following slow rewarming, core temperature increased to 36.5±1.2°C 48 hours after clopidogrel administration. In the control group, tympanic temperature ranged between 36.0 and 37.0°C.

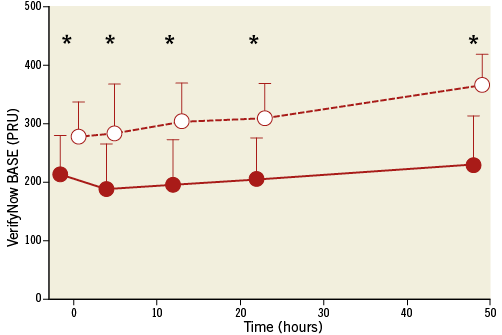

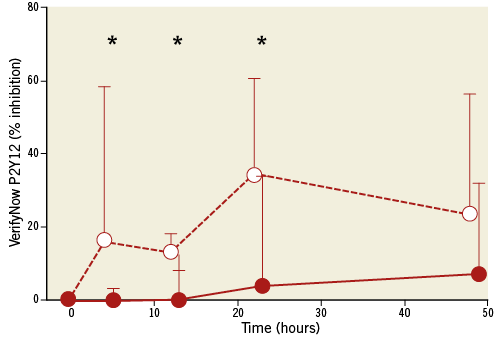

The post-cardiac arrest group had lower P2Y12 receptor blockade before clopidogrel, but its administration did not significantly reduce platelet reactivity in either group (Table 3). We observed significantly lower BASE in the post-cardiac arrest group, which persisted for up to 48 hours (Table 3, Figure 1). The antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel measured by VerifyNow and expressed as % inhibition was significantly lower in the post-cardiac arrest group (Figure 2). It was close to zero with an increase to only around 10% after 48 hours. The impedance aggregometry with Multiplate showed a decrease in platelet reactivity after clopidogrel in both groups but no significant difference between the groups was detected (Table 3).

Figure 1. Basal platelet reactivity (BASE) measured by VerifyNow P2Y12 assay in post-cardiac arrest (red circles) and control group (white circles). Patients receiving eptifibatide are not included. Average values with standard deviations are shown. Lower values mean lower platelet reactivity. PRU: P2Y12 reaction units; *: p<0.01

Figure 2. Platelet inhibition (% inhibition) measured by VerifyNow P2Y12 assay and calculated as [(1–(P2Y12 receptor blockade /BASE))×100] in post-cardiac arrest (red circles) and control (white circles) groups. Patients receiving eptifibatide are not included. Interquartile ranges are shown. *: p<0.05.

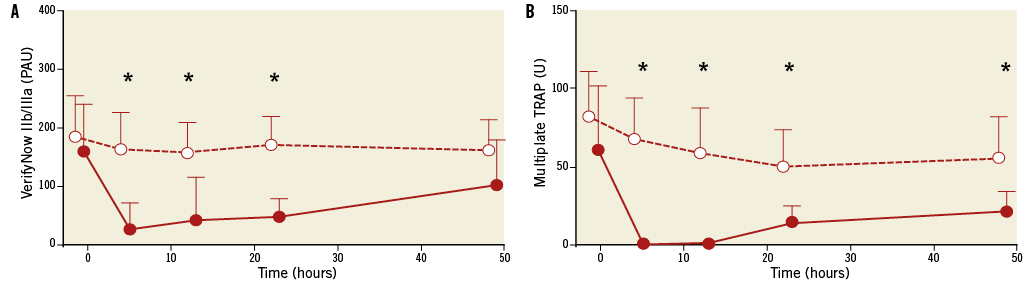

Post-cardiac arrest patients who received eptifibatide showed profound platelet inhibition measured both by VerifyNow IIb/IIIa and Multiplate TRAP test when compared to patients without eptifibatide (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Platelet reactivity in post-cardiac arrest patients undergoing PCI with eptifibatide (red circles) or without eptifibatide (white circles). Measurements were performed with VerifyNow IIb/IIIa test (A) and Multiplate TRAP test (B). Average values with standard deviations are shown. PAU: platelet aggregation unit; U: arbitrary unit; *: p<0.01

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that post-resuscitation syndrome with ongoing hypothermia is associated with decreased basal platelet reactivity (BASE) according to VerfyNow. Decreased BASE may be related to unknown effects of severe global ischaemia during untreated cardiac arrest, low flow state during chest compression and full reperfusion following ROSC. As such, our finding may represent an important but yet unreported component of post-resuscitation syndrome. There is evidence from animal studies which supports our finding13. It is less likely that decreased BASE was due to a 3 to 5°C reduction in core temperature since hypothermia may in fact stimulate platelet aggregation in vitro14 and in healthy volunteers15 by increasing ADP levels16,17. This is in accordance with our observation showing already decreased basal platelet reactivity on admission when hypothermia was only in the beginning phase and core temperature was still very close to normothermia.

Clopidogrel loading via nasogastric tube, on the other hand, did not significantly affect platelet function, at least during the first 48 hours according to VerifyNow P2Y12 % inhibition. This may be explained by a decrease in gastrointestinal motility and absorption associated with post-resuscitation syndrome, ongoing hypothermia18-20 and concomitant administration of opioids, sedatives and neuromuscular blocking agents21,22. In this context, it is important to emphasise that clopidogrel is a prodrug requiring liver metabolism which is likely to be slower due to decreased core temperature23,24. The virtually absent antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel demonstrated by us is in accordance with two previous preliminary studies also performed in the setting of cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation25,26. Moreover, there is growing evidence that clopidogrel does not offer early and effective antithrombotic protection even in normothermic patients with acute coronary syndrome without cardiac arrest27. It therefore appears that, in critical conditions, clopidogrel pharmacokinetics may be significantly different from those in healthy volunteers28,29. This is, at least in part, true also for the new, more potent P2Y12 inhibitors such as prasugrel, which has a less complex and more predictive metabolism, and ticagrelor, which does not need any metabolic activation. With both agents, the onset of relevant antiplatelet effect was delayed for several hours in the setting of STEMI without cardiac arrest30. There is very recent evidence in post-cardiac arrest patients undergoing hypothermia that prasugrel and ticagrelor may be more effective than clopidogrel but cannot fully prevent platelet non-responsiveness31.

In contrast to P2Y12 blockers, eptifibatide profoundly inhibited platelet function in post-cardiac arrest patients as measured both by VerifyNow IIb/IIIa assay and Multiplate TRAP test. This is consistent with in vitro studies demonstrating that eptifibatide prevented hypothermia-mediated platelet aggregation32. Eptifibatide has an immediate effect after bolus injection, which largely disappears six hours after the discontinuation of the infusion. Our results, showing profound platelet inhibition for at least 22 hours, are consistent with these pharmacokinetic findings. Accordingly, suboptimal platelet inhibition during and after PCI may be bridged by a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor which is practically important in case of very high thrombotic burden associated with complex PCI and stenting. However, such profound platelet inhibition should be weighed against an increased risk of bleeding due to possible traumatic injury related to chest compression and endotracheal intubation.

Limitations

Our study has some methodological limitations related particularly to platelet reactivity measurements after clopidogrel. We selected VerifyNow P2Y12 % inhibition because it is clinically relevant by being inversely related to stent thrombosis33. However, results of the % inhibition were discordant from platelet impedance aggregometry measurements by less extensively validated Multiplate assay34,35. Multiplate showed gradual decrease in platelet reactivity in each group without any difference between the groups. The explanation for this discordance is not known. However, both methods are not directly comparable. While VerifyNow uses optic aggregometry which detects change in light transmission caused by platelet aggregation, Multiplate requires platelets to adhere to electrodes, thereby measuring aggregation and adhesion as a change in impedance. VerifyNow seems to be more sensitive in detecting non-responders to clopidogrel36. On the other hand, VerifyNow may be influenced by cytochrome variants leading to decreased clopidogrel-mediated platelet inhibition which is not the case for Multiplate. It is also important to note that in our study temperature was automatically set to 37°C for VerifyNow but was adjusted to the actual patient temperature being 3 and 5°C lower in the hypothermia group for Multiplate. Last but not least, since platelet reactivity in our small study could not have shown a correlation to clinical events such as stent thrombosis, the practical importance of these measurements remains uncertain. In vitro measurements of platelet function represent only one component of prothrombotic potential which is likely to be affected by other factors such as changes in endothelium function and coagulation cascade37. This interplay of factors is probably even more complex during the post-resuscitation state with ongoing hypothermia than in elective PCI where P2Y12 treatment guided by VerifyNow did not improve the outcome38,39.

Conclusion

Post-resuscitation syndrome with ongoing hypothermia is associated with decreased platelet activity. Clopidogrel loading does not significantly affect platelet function during the first 48 hours. This is in contrast with eptifibatide which produces profound platelet inhibition and may be used to bridge insufficient inhibition by clopidogrel.

| Impact on daily practice If significant periprocedural platelet inhibition in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest in case of complex PCI is needed, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors should be used to bridge insufficient effects of oral P2Y12 inhibitors. However, such profound platelet inhibition should be weighed against increased risk of bleeding due to possible traumatic injury related to chest compression and endotracheal intubation. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the nurses, laboratory technicians and physicians who assisted in this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the University Medical Centre of Ljubljana, Tertiary Research Project Grant No. 20110171.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.