Abstract

Aims: Patients in a coma after cardiac arrest may have adversely affected drug absorption and metabolism. This study, the first of its kind, aimed to investigate the early pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of ticagrelor administered through a nasogastric tube (NGT) to patients resuscitated after an out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI).

Methods and results: Blood samples were drawn at baseline and at two, four, six, eight, 12, and 24 hours and then daily for up to five days after administration of a 180 mg ticagrelor loading dose (LD), followed by 90 mg twice daily in 44 patients. The primary endpoint was the occurrence of high platelet reactivity (HPR) 12 hours after the LD. Assessment by VerifyNow (VFN) showed 96 (15.25-140.5) platelet reactivity units (PRU), and five (12%) patients exhibited HPR. Multiplate analysis showed 19 (12-29) units (U) at twelve hours, and three patients (7%) had HPR. Ticagrelor and its main metabolite AR-C124910XX concentrations were 85.2 (37.2-178.5) and 18.3 (6.4-52.4) ng/mL. Median times to sufficient platelet inhibition below the HPR limit were 3 (2-6) hours (VFN) and 4 (2-8) hours (Multiplate).

Conclusions: Ticagrelor, administered as crushed tablets through a nasogastric tube, leads to sufficient platelet inhibition after 12 hours, and in many cases earlier, in the vast majority of patients undergoing pPCI and subsequent intensive care management after an OHCA.

Abbreviations

ADP: adenosine diphosphate

GPI: glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

HPR: high (on treatment) platelet reactivity

ICU: intensive care unit

IQR: interquartile range

LD: loading dose

NGT: nasogastric tube

OHCA: out of hospital cardiac arrest

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

PFT: platelet function tests

pPCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention

ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation

STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

TTM: targeted temperature management

VFN: VerifyNow

Introduction

Cardiac arrest is a relatively common complication of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). After the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), many patients are treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) and intensive care therapy, including a targeted temperature management (TTM) regimen if still unconscious1. Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is standard treatment after STEMI, and the newer platelet inhibitors prasugrel and ticagrelor are recommended over clopidogrel2. A previous study of comatose patients treated with hypothermia after cardiac arrest showed a delayed onset of platelet inhibition by clopidogrel compared with conscious patients3, and other studies have suggested a generally poorer uptake of medication in comatose patients4,5. Stent thrombosis rates have, in some studies, been reported to be higher among patients resuscitated after out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and treated with pPCI6,7. A possible explanation might be poor platelet inhibition due to affected drug absorption and metabolism in patients in a coma. A recent study on comatose patients with acute myocardial infarction found that a very high proportion of patients expressed high platelet reactivity (HPR) 24 hours after loading with clopidogrel, whereas prasugrel and ticagrelor seemed to provide more effective platelet inhibition8. Recently, two pilot studies on conscious patients found an improved and faster onset of action with ticagrelor if tablets were crushed and diluted in water before intake compared with tablets swallowed whole9,10.

The aim of this study was to assess platelet reactivity and pharmacokinetics after ticagrelor administration though a nasogastric tube (NGT) in comatose survivors of OHCA undergoing pPCI and subsequent intensive care management.

Methods

The TICOMA study was a prospective, observational, single-centre study conducted at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark, from October 2014 to October 2015. This is the first study to investigate both the early pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of ticagrelor administered through a NGT to STEMI patients resuscitated after OHCA and treated with pPCI.

Ticagrelor was chosen over prasugrel because it is the preferred adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor inhibitor in Denmark for both STEMI and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI) patients. In addition, data on crushed tablets administered to conscious patients have been encouraging. (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02175875)

STUDY POPULATION

During the inclusion period, all patients resuscitated but comatose after OHCA and triaged for acute coronary angiography due to STEMI were consecutively screened for study participation. Inclusion criteria for the trial were: recent (<3 hours) pPCI and therefore indication for oral P2Y12 inhibitor treatment, the patient being in a condition disabling normal oral administration of tablets and requiring NGT insertion, and consent by proxy for participation in the study as required by Danish law regarding clinical studies involving incapacitated patients. Exclusion criteria included: age <18 years old, absolute contraindications to antithrombotic treatment, ongoing treatment with an ADP inhibitor or oral anticoagulants before inclusion in the study and pregnancy. All patients were treated with pPCI according to department treatment protocols. Periprocedural treatment included, as per standard practice, 10,000 IU unfractionated heparin and 500 mg acetylsalicylic acid, administered intravenously in the pre-hospital setting or just before the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Additional use of anticoagulants was at the discretion of the treating physician; however, the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) was not encouraged due to interference with the platelet function tests (PFT).

STUDY-RELATED PROCEDURES

Tablets of ticagrelor, 180 mg as loading dose (LD) followed by 90 mg twice daily, were crushed in a mortar, dissolved in 50 mL of purified water and administered through an NGT immediately after PCI. Blood samples were collected from a cannula inserted in the radial artery. The first samples were collected before ticagrelor administration (t0). Thereafter, the samples were drawn repeatedly at two (±1), four (±1), six (±1), eight (±1), 12 (±1), and 24 (±2) hours, and then daily for an additional five days or until intensive care treatment was terminated. Platelet function was assessed using the VerifyNow® system (VFN) (Accumetrics Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), in a P2Y12 Reaction Units (PRU) test, and using the Multiplate® analyser (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) in adenosine diphosphate area under the curve units (AUC/U). HPR was defined as a PRU >208 for VFN and >46 U for Multiplate11. The primary endpoint was occurrence of HPR 12 hours after LD, measured by VFN and Multiplate. In addition, blood samples, drawn at similar time points, were stored for subsequent analysis for ticagrelor and its main metabolite AR-C124910XX concentrations (Covance Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study was conducted under Danish and international guidelines for good clinical practice (International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use-Good Clinical Practice [ICH-GCP]), and the study was approved by the regional scientific ethical committee and the Danish Medical Agency. The participating study persons were all comatose and therefore unable to give informed consent for inclusion in the acute phase. Thus, inclusion in the project before obtaining informed consent was justified according to Danish law considering incapacitated research participants: study procedures could start after acceptance from an appointed legal guardian (two medical doctors, not involved in the study). However, subsequent informed consent from the patient’s next-of-kin was to be obtained as soon as possible, as well as from the patient’s general practitioner/health officer. Patients who regained consciousness were asked to confirm the consent.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Baseline variables for the 44 patients are presented as percentages for categorical data and as median values followed by interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. In the graphs, plasma concentrations and platelet function results are presented as mean values followed by standard deviations. Baseline variables in patients with and without HPR at 12 hours are presented as percentages or median values with ranges and compared with the use of chi-square tests for categorical variables, t-tests for continuous variables with normal distributions, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables with non-normal distributions. Correlation between plasma concentrations and PFT were performed using Spearman’s correlation test. GraphPad Prism, version 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), was used for all statistical analysis and figures.

The time point where the platelet function test first reached the level below the HPR limit was registered for each patient for both Multiplate and VFN, and the median time at which values were below the HPR limit was calculated for the entire population.

Results

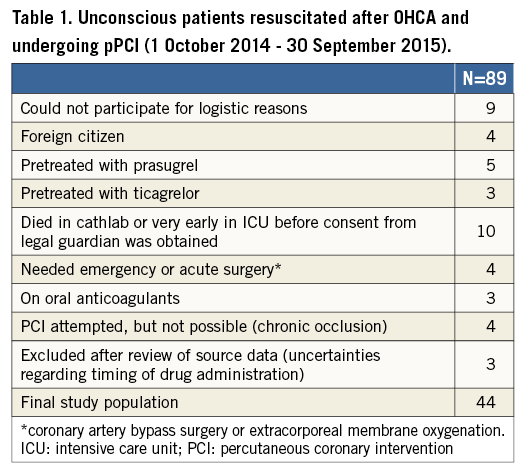

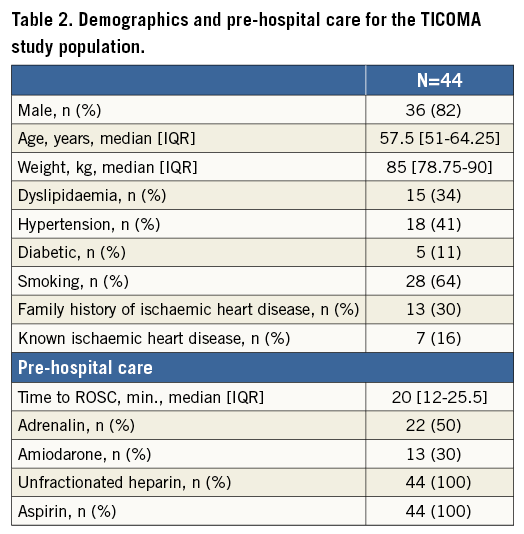

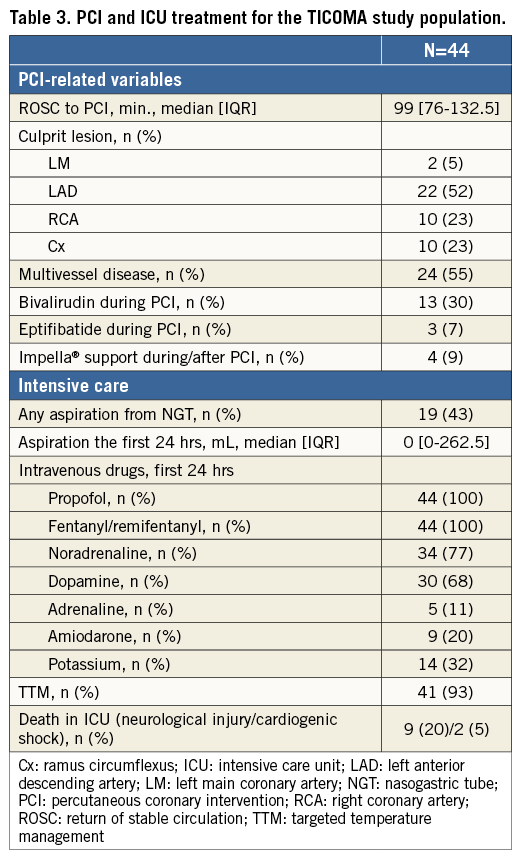

During the inclusion period of 12 months, 1,022 patients underwent primary PCI for STEMI in our institution. Eighty-nine patients (9%) were resuscitated after cardiac arrest and were screened for study participation (Table 1). Of 47 eligible patients, three had to be excluded from further analysis due to lack of documentation of study drug administration (exact time of administration) in the hospital charts. Thus, the study population consisted of 44 patients. Baseline characteristics are depicted in Table 2 and procedure- and ICU-related variables in Table 3. Forty-one (93%) patients underwent TTM at 36° Celsius for 24 hours12. Three patients treated with eptifibatide were excluded from platelet function testing but had plasma samples collected and stored for subsequent collective analyses of the concentration of ticagrelor and its main metabolite AR-C124910XX. One patient accepted study participation and platelet function testing after he regained consciousness except for the part involving plasma analyses to be performed outside of Denmark. Consequently, platelet function testing was performed in 41 patients and plasma analyses in 43 patients.

NGT treatment was continued for a median of four (three to five) days. At twelve hours, median VFN was 96 (15.25-140.5) PRU, and five of 41 (12%) patients exhibited HPR. Multiplate was 19 (12-29) U at twelve hours, and three patients (7%) had HPR. Median times to sufficient platelet inhibition below the HPR limit were 3 (2-6) hours (VFN) and 4 (2-8) hours (Multiplate).

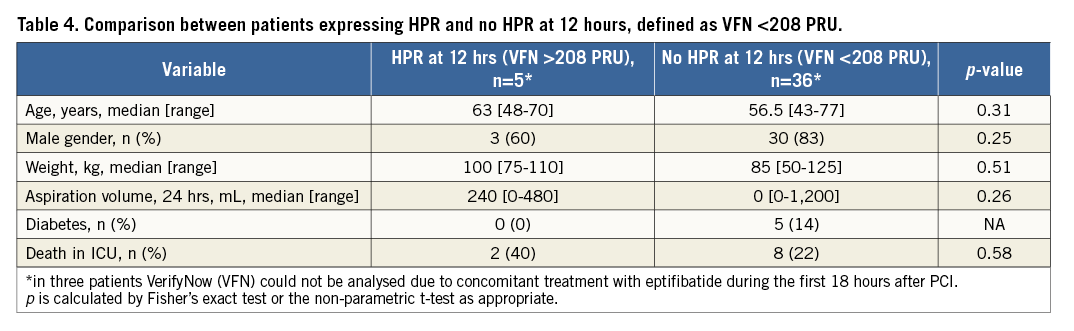

The five patients expressing HPR by VFN at 12 hours were older, had a higher body weight and had higher aspiration output from the NGT within the first 24 hours; however, none of these differences in characteristics reached statistical significance (Table 4).

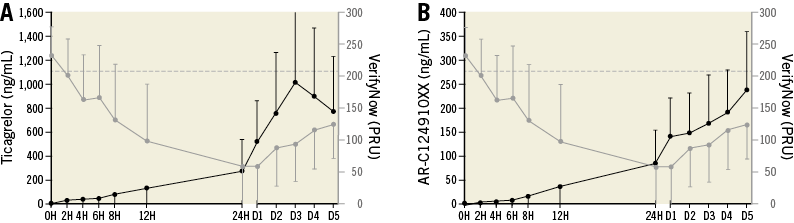

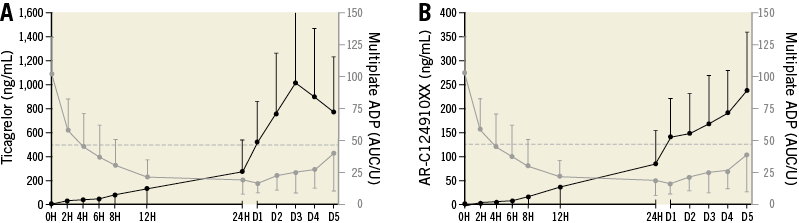

Platelet inhibition and plasma concentrations of ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX at the various time points after LD administration are shown in Figure 1A, Figure 1B (VFN) and Figure 2A, Figure 2B (Multiplate). Twelve hours after loading, median plasma concentrations were 85.2 (37.2-178.5) ng/mL for ticagrelor and 18.3 (6.4-52.4) ng/mL for AR-C124910XX. Peak concentrations of both components were not calculated since plasma concentrations continued to increase after maintenance doses were added to the treatment.

Figure 1. Pharmacokinetics and platelet reactivity after loading with 180 mg ticagrelor, crushed and diluted in water and administered through a nasogastric tube (NGT). A) Plasma concentrations of ticagrelor (black) and platelet reactivity by VerifyNow (VFN) (grey) (mean values/SD). The dotted line marks PRU >208, the level of high on treatment platelet reactivity according to the guidelines. B) Plasma concentrations of AR-C124910XX (black) and platelet reactivity by VerifyNow (grey) (mean values/SD). The dotted line marks PRU >208, the level of high on treatment platelet reactivity according to the guidelines. D: day; H: hours

Figure 2. Pharmacokinetics and platelet reactivity after loading with 180 mg ticagrelor, crushed and diluted in water and administered through a nasogastric tube (NGT). A) Plasma concentrations of ticagrelor (black) and platelet reactivity by Multiplate ADP (AUC/U) (grey) (mean values/SD). The dotted line marks U >46, the level of high on treatment platelet reactivity according to the guidelines. B) Plasma concentrations of AR-C124910XX (black) and platelet reactivity by Multiplate ADP (AUC/U) (grey) (mean values/SD). The dotted line marks U >46, the level of high on treatment platelet reactivity according to the guidelines11. D: day; H: hours

Platelet reactivity by VFN correlated with plasma concentrations of both ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX (Spearman rho=–0.678, p<0.0001, and –0.669, p<0.0001, respectively). Correlation analyses with Multiplate produced similar results (–0.631, p<0.0001, and –0.601, p<0.0001, respectively).

Eleven patients (25%) died in the intensive care unit, nine due to irreversible neurological injury and two in cardiogenic shock complicated by multi-organ failure. No cases of acute or early stent thrombosis were reported.

Discussion

The platelet inhibitory effect after loading with ticagrelor is directly related to the combined exposure of both ticagrelor and its active metabolite AR-C124910XX13. In a study on OHCA patients, Moudgil et al found that ticagrelor provided effective and sustained platelet inhibition within four hours after drug administration14. Tilemann et al found sufficient platelet inhibition by impedance aggregometry at 24 hours after cardiac arrest among 27 patients undergoing mild induced hypothermia15. Neither of these studies included pharmacokinetic data. It is noticeable that, in our TICOMA study, drug concentrations following administration of a 180 mg bolus were much lower than previously reported for conscious patients. Teng et al found peak values at around 550 ng/mL for ticagrelor and 175 ng/mL for AR-C124910XX four hours after administration of only 90 mg as an LD in healthy volunteers10. The LIQUID study, which compared absorption of crushed versus integral tablets of ticagrelor in STEMI patients, found peak values of ticagrelor at 1,490 ng/mL and of AR-C124910XX at 184 ng/mL four hours after intake of 180 mg crushed tablets in the semi-upright position16. Recently, a new study by Rollini et al added understanding to the effect of the other P2Y12 inhibitor, prasugrel. The study showed a faster onset of action and more potent antiplatelet effect with crushed prasugrel compared to whole tablets in a group of conscious STEMI patients17.

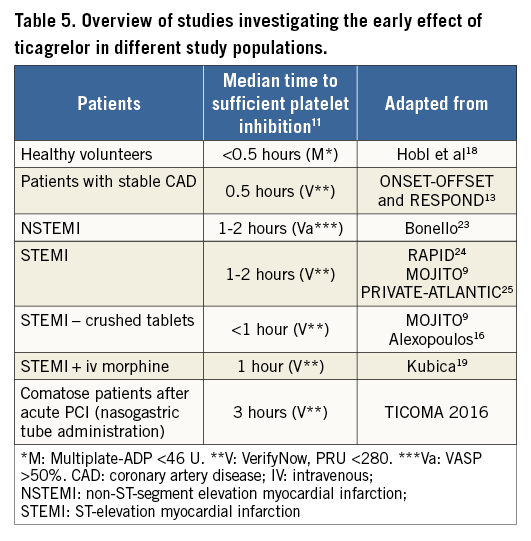

The comatose STEMI patients in the present study expressed much lower values even 12 hours after loading with 180 mg of ticagrelor, although a slow increase in plasma concentrations of both components as well as platelet inhibition was seen over the following days when maintenance doses were added to the treatment. All patients received morphine analogue medications in the intensive care unit (ICU). It has previously been shown that morphine decreases ticagrelor concentrations but not its antiplatelet effect in healthy volunteers18, but in a STEMI population concomitant morphine administration is related to a delayed and attenuated ticagrelor exposition and platelet inhibition19. Platelet inhibition results in patients receiving ticagrelor in various clinical settings are summarised in Table 5. The present study adds to the understanding of platelet inhibition in a less investigated patient subset, namely comatose patients. Whether hypothermia affects platelet function is controversial. Kander et al studied the in vitro effect of induced hypothermia and hyperthermia on blood from patients undergoing ticagrelor- and aspirin-mediated platelet inhibition. In vitro hypothermia to 33°C markedly increased platelet activity measured by flow cytometry but not by Multiplate analysis20. Based on these findings, it seems reasonable to suggest that the slower onset of platelet inhibition in the present study compared to reports from conscious patients is probably due to slower ventricular absorption, and not to the mild temperature management.

Recently, hypothermia to 33°C as standard treatment to prevent neurological damage after OHCA was challenged by the TTM study, which found equal survival rates and neurological outcome in patients managed at 33 and 36 degrees. In the TTM study, coagulation parameters did not differ between the two treatment groups, although platelet function analyses were not performed21. In our institution, we have adapted the 36°C regimen as standard of care to avoid other complications related to more profound cooling such as bradycardia, the need for deeper sedation due to shivering, etc.

Fast and reversible platelet inhibition is now also possible with cangrelor, a new high-affinity, reversible intravenous antagonist of P2Y12. Co-administration with ticagrelor is possible22. Cangrelor was not available to patients during the TICOMA study. To be able to tailor antiplatelet therapy for comatose patients in the future, knowledge of ticagrelor’s onset of action is important if other platelet inhibitors such as GPI or cangrelor are considered as bridging therapy during the first hours after PCI, something which was recently recommended in a consensus statement from the European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI)/Stent for Life (SFL) groups on invasive coronary treatment strategies for out of hospital cardiac arrest1. We believe that the present study has provided this information.

Limitations

Our results must be evaluated in the light of some limitations. First, this is a small sample size without any control group, although the enrolment was prospective, consecutive and with few exclusion criteria. Second, ticagrelor was the only P2Y12 inhibitor studied as we did not find it ethically acceptable to randomise between clopidogrel and ticagrelor, based on the previous reports of inferior platelet inhibitory effects of clopidogrel in comatose patients3. A comparison between ticagrelor and prasugrel between the patients could have been interesting but would also have increased the number of patients needed in the study. Third, more frequent samplings, both early (0-2 hours) and late (after 12 hours), may have added to the results; however, the sampling times were more frequent than previously reported in other studies and two PFT were used. Fourth, the study did not compare comatose patients with conscious STEMI patients. However, several studies have addressed this matter before, and it was decided to use historical data and defer from the frequent blood sampling in conscious patients.

Platelet reactivity at 12 hours was chosen as the primary endpoint in the present study, mainly because earlier studies on clopidogrel have shown HPR even after 24 hours. Due to the comatose state of the study participants, the co-administration of morphine and poor gastric motility, we expected ticagrelor to perform much worse than was actually shown in the study.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that ticagrelor, administered as crushed tablets through an NGT, leads to sufficient platelet inhibition after 12 hours in the vast majority of comatose STEMI patients after undergoing pPCI, with a median time to guideline-based platelet inhibition levels of around three to four hours.

| Impact on daily practice Ticagrelor administered as crushed tablets through an NGT leads to sufficient platelet inhibition after 12 hours in the vast majority of comatose patients after undergoing pPCI, with a median time to guideline-based platelet inhibition levels of around three to four hours. Thus, in comatose patients, intravenous antiplatelet therapy may be considered in the early hours after primary PCI if there is an increased risk of stent thrombosis. |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the nurses at the Cardiac Intensive Care unit 2143, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, for supporting the study, and Dr Jakob Hartvig Thomsen for assisting with the inclusion procedure.

Funding

The study was designed by the investigators and conducted with support from the investigator-sponsored study programme of AstraZeneca.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.