Abstract

Background: Early P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy has emerged as a promising alternative to 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Aims: In this single-arm pilot study, we evaluated the feasibility and safety of ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy directly following PCI in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS).

Methods: Patients received a loading dose of ticagrelor or prasugrel before undergoing platelet function testing and subsequent PCI using new-generation drug-eluting stents. The stent result was adjudicated with optical coherence tomography in the first 35 patients. Ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy was continued for 12 months. The primary ischaemic endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, definite or probable stent thrombosis or stroke within 6 months. The primary bleeding endpoint was Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 2, 3 or 5 bleeding within 6 months.

Results: From March 2021 to March 2022, 125 patients were enrolled, of whom 75 ultimately met all in- and exclusion criteria (mean age 64.5 years, 29.3% women). Overall, 70 out of 75 (93.3%) patients were treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy directly following PCI. The primary ischaemic endpoint occurred in 3 (4.0%) patients within 6 months. No cases of stent thrombosis or spontaneous myocardial infarction occurred. The primary bleeding endpoint occurred in 7 (9.3%) patients within 6 months.

Conclusions: This study provides first-in-human evidence that P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy directly following PCI for NSTE-ACS is feasible, without any overt safety concerns, and highlights the need for randomised controlled trials comparing direct P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy with the current standard of care.

Introduction

In patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is the current standard of care1. However, the reduction in ischaemic events as a result of DAPT is at least partly counterbalanced by an increase in bleeding. Contrary to popular belief, these bleeding events are far from harmless and are associated with increased mortality2. In fact, the mortality risk associated with major bleeding is equal to the risk associated with recurrent myocardial infarction (MI)3. Hence, identifying the antithrombotic approach with the best trade-off between ischaemic and bleeding events remains a matter of intense investigation.

Traditionally, novel antithrombotic strategies have predominantly been tested on a background of aspirin, but aspirin itself is also associated with increased bleeding, challenging the paradigm that this agent should remain the cornerstone of antithrombotic treatment4. In recent years, several large-scale randomised controlled trials have demonstrated that early aspirin withdrawal (i.e., P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy) can significantly reduce bleeding without an increase in either stent-related or non-stent-related ischaemic events5678910. However, all these trials included at least 1 to 3 months of DAPT before switching to P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy, whereas the average daily bleeding risk is highest during this early period following PCI11. Therefore, given the recent advances in stent technology and the introduction of potent P2Y12 inhibitors (i.e., ticagrelor and prasugrel), we set out to explore if direct P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy was feasible and safe in patients with NSTE-ACS undergoing PCI121314.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

The Optical Coherence Tomography-Guided PCI with Single-Antiplatelet Therapy (OPTICA) study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04766437) was a single-arm pilot study with 75 patients to evaluate the feasibility and safety of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy using ticagrelor or prasugrel directly following PCI using new-generation drug-eluting stents (DES). The study was conducted in the two affiliated hospitals of the Amsterdam University Medical Center. Both hospitals are high-volume, tertiary PCI centres situated in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. To enhance patient safety, all patients underwent platelet function testing before PCI, and the first 35 patients underwent optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging after PCI. A stopping rule based on the occurrence of stent thrombosis was incorporated into the study design. If two or more cases of stent thrombosis occurred, patient enrolment would be prematurely halted, and patients on ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy would be switched to the current standard of care: 12 months of DAPT. All study participants provided written informed consent prior to undergoing any study-specific procedures. An independent data and safety monitoring board provided external oversight to ensure the safety of the study participants. The institutional review boards of both participating centres approved the study protocol.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Patients presenting with acute chest pain (or equivalent symptoms) without persistent ST-segment elevation (i.e., NSTE-ACS) who were scheduled for coronary angiography and possible (ad hoc) PCI using new-generation DES were screened and considered eligible for the study. Diagnosis was classified as non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina based on the diagnostic criteria outlined in current guidelines1. In short, patients were diagnosed with NSTEMI in the presence of a rise and/or fall pattern of troponin with at least one value above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit. If patients did not have elevated troponin levels or a rise and/or fall pattern, they were diagnosed with unstable angina. Patients with an allergy or contraindication to both ticagrelor and prasugrel were excluded, as were patients requiring chronic oral anticoagulant therapy. Patients who had an overriding indication for DAPT (e.g., recent PCI or ACS) and patients requiring complex PCI were also excluded. Complex PCI was defined as PCI of left main disease, chronic total occlusion, a bifurcation lesion requiring two-stent treatment, a saphenous or arterial graft lesion, or severely calcified lesions.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY BEFORE PCI

Patients received a loading dose of 180 mg ticagrelor or 60 mg prasugrel at least two hours prior to the index PCI. The agent of choice was at the discretion of the treating physician. If patients were on a chronic aspirin regimen or received an aspirin loading dose (e.g., in the ambulance) prior to inclusion in the study, aspirin was discontinued on the day of the index PCI at the latest. In line with current guidelines, patients were treated with 2.5 mg fondaparinux subcutaneously once daily alongside ticagrelor or prasugrel until revascularisation1.

PLATELET FUNCTION TESTING

Platelet reactivity was assessed using the VerifyNow system (Werfen) and expressed as P2Y12 reaction units (PRU). High platelet reactivity was defined as PRU ≥208, in line with expert consensus15. Blood samples for platelet function testing were collected at least two hours after administration of the ticagrelor or prasugrel loading dose using 2 ml blood containers (VACUETTE 9NC coagulation sodium citrate 3.2%; Greiner Bio-One). Blood samples were drawn from a venous cannula or arterial sheath at the start of coronary angiography. Blood samples were subsequently processed by trained research staff in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Blood samples were analysed within 30 minutes after sample collection to reduce the risk of error measurements due to extra platelet activation, haemolysis, or coagulation.

INDEX PCI AND ADJUDICATION OF STENT RESULT

All patients received a weight-adjusted dose of unfractionated heparin during coronary angiography and an additional dose after 60 minutes if the activated clotting time fell below 250 seconds. Index PCI was performed with the intention to treat the culprit vessel using new-generation DES. In case of multiple lesions, the decision for direct revascularisation of non-culprit lesions or a staged approach was at the discretion of the treating physician. Directly following PCI, the stent result was adjudicated based on the criteria shown in Supplementary Table 2. In the first 35 patients, the stent result was adjudicated per protocol using OCT imaging. An imaging catheter (Dragonfly OPTIS; Abbott) was positioned distal to the target lesion(s) and pulled back to the aorta at an automatic speed of 36 mm/s. OCT-guided stent optimisation (e.g., in case of stent malapposition) was encouraged. The use of OCT imaging in the remaining 40 patients was at the discretion of the treating physician.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY AFTER PCI

Patients with adequate inhibition of platelet reactivity and an optimal stent result continued to receive 90 mg ticagrelor twice daily or 10 mg prasugrel once daily without concurrent aspirin for up to 12 months. Of note, prasugrel dose reduction (5 mg instead of 10 mg once daily) was not allowed under the study protocol. Therefore, patients with an indication for prasugrel dose reduction (i.e., patients aged ≥75 years or with a body weight <60 kg) were solely treated with ticagrelor. In the case of high platelet reactivity or a suboptimal stent result, aspirin was added to the antiplatelet regimen. Prior to hospital discharge, all patients were informed about the importance of medication adherence. Patients with agent-specific side effects were allowed to switch from ticagrelor to prasugrel or vice versa during follow-up. In case both prasugrel and ticagrelor were contraindicated or not tolerated, clopidogrel in combination with aspirin was considered as the preferred alternative antiplatelet regimen. If patients developed atrial fibrillation or another indication for chronic oral anticoagulant therapy during follow-up, an oral anticoagulant in combination with clopidogrel for up to 12 months was recommended. Switching between P2Y12 inhibitors was done according to the algorithm recommended by the European Society of Cardiology16.

FOLLOW-UP

Clinical follow-up was performed at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months by telephone contact. Patients also attended in-person visits at the outpatient clinic at regular intervals. During follow-up, investigators assessed the occurrence of any adverse events, including ischaemic and bleeding events. Furthermore, patient-reported treatment adherence was checked at each follow-up and treatment adherence was corroborated by prescription refill data reported by the pharmacy. Any modification to the antiplatelet regimen during follow-up was documented, including the date and reason for modification.

STUDY ENDPOINTS

The primary ischaemic endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality, MI, definite or probable stent thrombosis, or stroke within 6 months following PCI. MI was defined according to the fourth universal definition, whereas stent thrombosis was classified according to the Academic Research Consortium criteria1718. The primary bleeding endpoint was major or minor bleeding defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2, 3 or 5 bleeding within 6 months following PCI19. BARC type 3 or 5 bleeding was considered major bleeding, while type 2 was considered minor bleeding. All primary endpoints were adjudicated by two authors (NMRS and BEPMC), who had full access to the patients’ health records. Secondary endpoints included any repeat revascularisation and the individual components of the primary endpoints within 6 months following PCI.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The primary objective of our study was descriptive in nature. Therefore, no formal sample size calculation was performed. Continuous variables were reported as mean±standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate. Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage (%). Cumulative incidences of the primary ischaemic and bleeding endpoints were assessed using Kaplan-Meier estimates at 6 months. Data from patients who did not have a primary endpoint event between the index PCI and 6 months were censored at the time of death (except for the ischaemic endpoint), time of last follow-up or 6 months, whichever came first. Analyses of the primary ischaemic and bleeding endpoints were performed in the intention-to-treat population, which consisted of all patients who met the in- and exclusion criteria. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM).

Results

PATIENT INCLUSION

From March 2021 to March 2022, 125 out of 144 screened patients provided informed consent for participation in the study. The in- and exclusion criteria were reassessed during coronary angiography and PCI, ultimately leading to the inclusion of 75 patients. The most common reasons for exclusion after enrolment were no significant coronary artery stenosis during coronary angiography, conservative management (e.g., target vessel was too small for intervention) or complex PCI. A detailed flowchart is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flowchart. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age at the time of enrolment was 64.5±11.6 years, and 29.3% of patients were female. Eighteen patients (24.0%) had diabetes mellitus, and 28.0% of patients were active smokers at the time of enrolment. Only 16.0% of patients had undergone a PCI prior to the index procedure. The majority of patients (85.3%) presented with NSTEMI, while all other patients (14.7%) were diagnosed with unstable angina. New ischaemic ECG changes, predominantly T-wave inversions and ST-segment depressions, were present in over half of all patients (57.3%). Patients were discharged from the hospital after a median of 3 days (IQR: 2 to 5). At the time of admission, 15 patients (20.0%) were on a chronic aspirin regimen, and 55 patients (73.3%) received an aspirin loading dose, most often in the ambulance, before undergoing PCI.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| N=75 | |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age (yrs) | 64.5±11.6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | 28.2±4.5 |

| Female sex | 22 (29.3%) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Current smokers | 21 (28.0%) |

| Hypertension | 43 (57.3%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 32 (42.7%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (24.0%) |

| Insulin-dependent | 5 (6.7%) |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 20 (26.7%) |

| Medical history | |

| Prior MI | 7 (9.3%) |

| Prior stroke or TIA | 4 (5.3%) |

| Prior PCI | 12 (16.0%) |

| Prior CABG | 0 (0.0%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 (4.0%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1 (1.3%) |

| Renal insufficiency† | 7 (9.3%) |

| Major bleeding | 1 (1.3%) |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Unstable angina | 11 (14.7%) |

| NSTEMI | 64 (85.3%) |

| New ischaemic ECG changes‡ | 43 (57.3%) |

| Days in hospital (days) | 3 (2-5) |

| Values are presented as mean±standard deviation, median (IQR) or number of patients (percentage). *Body mass index was missing in 5 cases (6.7%). †Renal insufficiency was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. ‡New ischaemic ECG changes included transient ST-segment elevation, persistent or transient ST-segment depression, T-wave inversion, flat T waves, or pseudonormalisation of T waves. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; ECG: electrocardiogram; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA: transient ischaemic attack | |

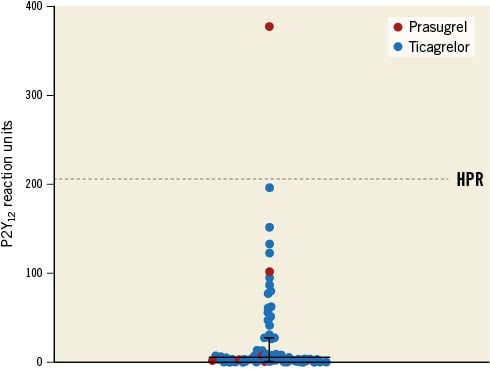

PLATELET FUNCTION TESTING

Figure 2 provides an overview of the individual PRU measurements. Before the index procedure, 67 (89.3%) and 8 (10.7%) patients received an oral loading dose of ticagrelor or prasugrel, respectively. All patients, with the exception of one, had adequate inhibition of platelet reactivity with a median PRU value of 6 (IQR: 2 to 28). In the only patient without adequate inhibition of platelet reactivity, high platelet reactivity was possibly due to a short interval (54 min) between the prasugrel loading dose and platelet function testing. However, this was not confirmed by repeated platelet function testing. Median PRU values did not differ between patients treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel (6 [IQR: 2 to 28] vs 3 [IQR: 2 to 79]; p=0.97).

Figure 2. Scatterplot of individual P2Y12 reaction unit measurements. The horizontal line represents the median P2Y12 reaction unit value, and the whiskers represent the 25th and 75th percentile range. The dotted line represents the threshold for high platelet reactivity. HPR: high platelet reactivity

PROCEDURAL CHARACTERISTICS

Procedural characteristics are shown in Table 2. Most patients underwent PCI via radial access (96.0%), and, per the study design, all included patients were treated with at least one new-generation DES. Eighteen patients (24.0%) underwent multivessel PCI and 29.3% of patients had more than one treated lesion during the index procedure. The median number of implanted stents per patient was 1 (IQR: 1 to 2), and the median total stent length was 33 mm (IQR: 20 to 46). The median minimum stent diameter was 3.00 mm (IQR: 2.75 to 3.50). Almost half of all patients (45.3%) underwent OCT imaging during the index procedure. OCT-guided stent optimisation was performed in 10 patients (13.3%) through post-dilatation (10.7%) or additional stenting (2.7%). After the procedure, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade 3 was achieved in 106 out of 106 of lesions (100%). Still, four patients (5.3%) had a suboptimal stent result or were otherwise deemed unsuitable for ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy by the treating physician. Two of these four patients had an actionable edge dissection, which was complicated in the first case by temporary no-reflow and in the second case required additional stenting of the distal left main. One patient had a total stent length of 172 mm, and one patient had a severely tortuous stent trajectory. Alongside the one patient with high platelet reactivity, these patients remained on DAPT following PCI. Hence, 70 (93.3%) patients were treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy directly following PCI.

Table 2. Procedural characteristics.

| N=75 | |

|---|---|

| Vascular access site per patient | |

| Radial | 72 (96.0%) |

| Femoral | 3 (4.0%) |

| Treated vessel(s) | |

| Left main coronary artery | 1 (1.3%) |

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | 45 (60.0%) |

| Left circumflex coronary artery | 24 (32.0%) |

| Right coronary artery* | 23 (30.7%) |

| Two or more vessels treated† | 18 (24.0%) |

| Lesions treated per patient | 1 (1-2) |

| 1 lesion | 53 (70.7%) |

| 2 lesions | 13 (17.3%) |

| ≥3 lesions | 9 (12.0%) |

| Number of stents used per patient | 1 (1-2) |

| 1 stent | 49 (65.3%) |

| 2 stents | 12 (16.0%) |

| ≥3 stents | 14 (18.7%) |

| Total stent length per patient (mm) | 33 (20-46) |

| Minimum stent diameter per patient (mm) | 3.00 (2.75-3.50) |

| Procedure time (min) | 43 (33-65) |

| Antiplatelet regimen directly following procedure | |

| Ticagrelor monotherapy | 64 (85.3%) |

| Prasugrel monotherapy | 6 (8.0%) |

| Other‡ | 5 (6.7%) |

| Values are presented as median (IQR) or number of patients (percentage). *Right coronary artery includes right posterolateral branch, left anterior descending includes diagonal branches, left circumflex artery includes marginal branches. †Two or more vessels treated during index procedure. ‡One patient was treated with prasugrel and aspirin (1.3%) and four patients were treated with ticagrelor and aspirin (5.3%). | |

OUTCOMES

All included patients completed 6 months of follow-up. Clinical outcomes within this timeframe are presented in Table 3. The primary ischaemic endpoint occurred in 3 patients (4.0%) within 6 months following PCI. Two patients (2.7%) suffered from a coronary intervention-related MI (Type 4a) due to temporary occlusion of a septal and diagonal side branch, respectively, during the index PCI. In both cases, side branch occlusion was caused by plaque shift and not thrombus formation. One patient (1.3%), who had undergone PCI of the proximal to distal left anterior descending artery (LAD) and ostial to mid-ramus circumflex artery (RCx) 53 days before, suffered from a Type 2 MI due to severe hypertension. During the index procedure, intermediate lesions in the right coronary artery (RCA) and ostial LAD were treated conservatively. The stent result in the LAD and RCx was good upon repeat coronary angiography, with no angiographic evidence of thrombus, and both the instantaneous wave-free ratio and fractional flow reserve measurements of the remaining ostial LAD and RCA lesions were negative. No cases of stent thrombosis or spontaneous MI (i.e., Type 1 MI) occurred within 6 months. The primary bleeding endpoint occurred in seven patients (9.3%) within 6 months. Two patients (2.7%) had a major bleeding event. One patient suffered from ocular bleeding related to macular degeneration 60 days after the index procedure. Another patient required a blood transfusion due to a significant drop in haemoglobin 71 days after the index procedure, presumably caused by chronic bleeding from Cameron lesions identified during gastroscopy. Out of the seven minor bleeding events which occurred in five patients (6.7%), four were access-site related, one was oropharyngeal, one was nasal and one was traumatic. Four patients (5.3%) underwent repeat revascularisation within 6 months. All revascularisations were non-target vessel related, and two out of the four procedures were part of a planned staged procedure. All patients undergoing elective, non-target vessel revascularisation continued ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy unless the procedure was considered complex (e.g., PCI of chronic total occlusion). Four other patients (5.3%) also underwent repeat coronary angiography within 6 months, indicated by either recurrent or persistent angina or dyspnoea, all without evidence of new stent-related (or non-stent-related) stenosis.

Table 3. Clinical outcomes at 6-month follow-up.

| N=75 | |

|---|---|

| Primary ischaemic endpoint* | 3 (4.0%) |

| All-cause death | 0 (0.0%) |

| Cardiac death | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-cardiac death | 0 (0.0%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (4.0%) |

| Type 1 | 0 (0.0%) |

| Type 2 | 1 (1.3%) |

| Type 3 | 0 (0.0%) |

| Type 4a | 2 (2.7%) |

| Type 4b | 0 (0.0%) |

| Type 4c | 0 (0.0%) |

| Type 5 | 0 (0.0%) |

| Probable or definite stent thrombosis | 0 (0.0%) |

| Definite | 0 (0.0%) |

| Probable | 0 (0.0%) |

| Stroke | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ischaemic | 0 (0.0%) |

| Haemorrhagic | 0 (0.0%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0%) |

| Primary bleeding endpoint† | 7 (9.3%) |

| BARC type 2 bleeding | 5 (6.7%) |

| BARC type 3 bleeding | 2 (2.7%) |

| BARC type 5 bleeding | 0 (0.0%) |

| Secondary endpoints | |

| Repeat revascularisation | 4 (5.3%) |

| Target lesion revascularisation | 0 (0.0%) |

| Target vessel revascularisation | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-target vessel revascularisation | 4 (5.3%) |

| Values are presented as number of patients and Kaplan–Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence of the clinical endpoints. *The primary ischaemic endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, definite or probable stent thrombosis or stroke within 6 months following PCI. †The primary bleeding endpoint was major or minor bleeding defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 2, 3 or 5 bleeding within 6 months following PCI. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; PCI: percutaneous coroanry intervention | |

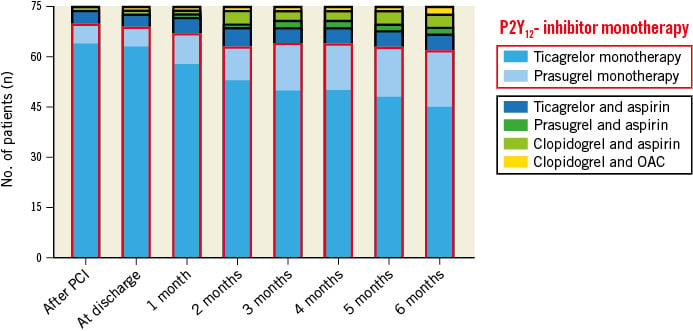

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

Adherence to the study regimen is shown in Figure 3. Directly following PCI, 93.3% of patients were on ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy. At 1, 3 and 6 months, 89.3%, 85.3% and 82.7% of patients remained on ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy, respectively. During follow-up, 24 treatment modifications occurred in 20 (26.7%) patients after a median follow-up of 60 days (IQR: 32 to 130). Eleven (14.7%) patients switched from ticagrelor to prasugrel monotherapy during follow-up, mainly due to presumed side effects of ticagrelor. For similar reasons four patients (5.3%) in whom prasugrel was contraindicated, mainly because the patients were 75 years old or older, switched from ticagrelor monotherapy to clopidogrel and aspirin. Two patients (2.7%) switched from ticagrelor monotherapy to ticagrelor and aspirin after complex, non-target vessel revascularisation during follow-up, and two patients (2.7%) switched to clopidogrel and an oral anticoagulant due to new onset atrial fibrillation. An overview of all treatment modifications is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 3. Antithrombotic treatment during follow-up. OAC: oral anticoagulant

Discussion

Our pilot study was designed to examine the feasibility and safety of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy using ticagrelor or prasugrel directly after PCI in patients with NSTE-ACS. P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy was feasible in most patients and, more importantly, not associated with any overt safety concerns given the absence of stent thrombosis and spontaneous MI within the first six months of follow-up (Central illustration). Although other investigators have previously shown that direct P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy using prasugrel was feasible and safe in patients undergoing PCI for chronic coronary syndrome (CCS), our pilot study is the first to examine aspirin withdrawal directly after PCI for NSTE-ACS20.

This pilot study was only possible because of the recent advances made in stent technology and the advent of potent P2Y12 inhibitors. Compared to early-generation DES, the new-generation DES used in the present study have thinner struts and better biocompatible polymers21. These technological advances in combination with improved stent implantation techniques have led to a very low rate of stent-related adverse events22. In the present era, stent thrombosis is most often a consequence of suboptimal stent deployment and not device thrombogenicity, limiting the need for prolonged DAPT after successful stent implantation23. Furthermore, potent P2Y12 inhibitors such as ticagrelor and prasugrel exert a stronger and more reliable inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation compared to clopidogrel24. Pharmacological studies have demonstrated that the antithrombotic potency of ticagrelor and prasugrel alone is similar to the potency of ticagrelor or prasugrel combined with aspirin, providing a mechanistic rationale for P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy2526. In the TWILIGHT (Ticagrelor with Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients after Coronary Intervention) Platelet Sub-study, data on thrombogenicity under dynamic flow conditions showed that the antithrombotic potency of ticagrelor monotherapy was similar to that of ticagrelor combined with aspirin in high-risk patients undergoing PCI25. Similarly, Armstrong et al used platelet-rich plasma from healthy volunteers to demonstrate that prasugrel induces a potent inhibition of platelet aggregation even without aspirin and that the addition of aspirin does not further increase the inhibition of platelet aggregation26.

In recent years, six randomised controlled trials, including over thirty-five thousand patients, have examined the clinical effects of early P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy after PCI for CCS and ACS. In contrast to our study, the other trials included at least 1 to 3 months of DAPT before switching to P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy. Overall, five of these six trials showed that early P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy reduced clinically relevant bleeding678910. Only in the GLOBAL LEADERS trial, ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months preceded by 1 month of DAPT did not reduce major bleeding compared to aspirin monotherapy for 12 months preceded by 12 months of DAPT5. Three out of six trials conducted a formal non-inferiority analysis with regard to ischaemic events and all three trials met their prespecified criteria for non-inferiority679. In the pivotal TWILIGHT trial, the rate of all-cause mortality, MI or stroke was similar in patients treated with ticagrelor monotherapy and DAPT (3.9% vs 3.9%, hazard ratio [HR] 0.99, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.78-1.25; PNI<0.001)9. Conversely, the STOPDAPT-2 ACS (ShorT and OPtimal Duration of Dual AntiPlatelet Therapy-2 Study for the Patients With ACS) trial failed to attest the non-inferiority of clopidogrel monotherapy after 1 to 2 months compared to 12 months of DAPT with regard to the net clinical benefit endpoint consisting of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis and TIMI major or minor bleeding (3.2% vs 2.8%, HR 1.14, 95% CI: 0.80-1.62; PNI=0.06). Notably, the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke and stent thrombosis was numerically higher in the clopidogrel monotherapy group (2.8% vs 1.9%, HR 1.50, 95% CI: 0.99-2.26)10. Importantly, current guidelines only recommend clopidogrel for ACS patients when prasugrel and ticagrelor are contraindicated or cannot be tolerated1. Possibly, clopidogrel is therefore also less suitable as an agent of choice in the setting of monotherapy compared to ticagrelor and prasugrel.

The ASET (Acetyl Salicylic Elimination Trial) Pilot Study was the first to examine the feasibility and safety of prasugrel monotherapy directly following everolimus-eluting stent implantation in patients with CCS and low anatomic complexity20. In the ASET Pilot Study, 201 patients were treated with DAPT prior to the index procedure and started prasugrel directly after PCI. Overall, 98.5% of patients were adherent to prasugrel monotherapy, and there were no cases of stent thrombosis or spontaneous MI at 3-month follow-up. One patient (0.5%) suffered from a fatal intracranial bleeding in the days following PCI, although the overall rate of bleeding (BARC type 1 to 5) was extremely low at 0.5%. The bleeding rate in our study was higher, but most bleeding events were minor and primarily access-site related. The ASET investigators maximised safety by applying stringent patient selection focused on enrolling only low-risk patients. Consequently, patients were possibly not only at low ischaemic risk, but also at low bleeding risk. Currently, the ASET investigators are evaluating direct prasugrel monotherapy in a larger cohort of 400 patients undergoing PCI for CCS and NSTE-ACS in the ASET JAPAN Pilot Study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05117866).

Ultimately, large-scale randomised controlled trials will need to examine the efficacy and safety of direct P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy compared to the current standard of care; 12 months of DAPT. Currently, both the LEGACY (Less Bleeding by Omitting Aspirin in Non-ST-segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05125276) and NEOMINDSET (PercutaNEOus Coronary Intervention Followed by Monotherapy INstead of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in the SETting of Acute Coronary Syndromes; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04360720) trials are comparing direct P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy to conventional DAPT in patients undergoing PCI for ACS. Importantly, both trials allow for prasugrel monotherapy in the study design. Thus far, ticagrelor has been predominantly used in trials evaluating P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy, and experience with prasugrel in this setting has been limited27. However, treatment modifications in trials evaluating different antithrombotic strategies are common, with approximately 10-15% of all patients altering treatment during follow-up5928. Prasugrel could serve as an alternative in patients not tolerating ticagrelor2930. For example, in this pilot study, eleven patients (14.7%) were switched from ticagrelor to prasugrel monotherapy and were therefore able to continue P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, there was no comparator or control group. Therefore, it is not possible to draw conclusions in terms of the safety and efficacy of ticagrelor or prasugrel monotherapy compared to the current standard of care; 12 months of DAPT. Second, important exclusion criteria such as the exclusion of complex PCI should be considered when extrapolating the results to a more general population. Third, all patients in the present study underwent platelet function testing, which is not reflective of daily clinical practice. Still, high platelet reactivity in prasugrel- or ticagrelor-treated patients was rare in our study, consistent with the literature31. Therefore, routine platelet function testing in future randomised controlled trials and daily clinical practice might not be necessary. Fourth, almost half of the patients in the present study underwent OCT-guided PCI, minimising the risk of ischaemic events post-PCI since the stent result is strongly associated with stent-related ischaemic events during follow-up23. Finally, the endpoints were adjudicated by two authors and not an independent clinical event committee.

Conclusions

Completely omitting aspirin after successful PCI in NSTE-ACS is feasible and not associated with any overt safety concerns given the absence of stent thrombosis and spontaneous MI within the first six months of follow-up. Larger randomised controlled trials are warranted to compare the efficacy and safety of completely omitting aspirin with 12 months of DAPT.

Impact on daily practice

Twelve months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) has long been the standard of care after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) without ST-segment elevation, but early or even direct P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy has emerged as a promising alternative that can possibly reduce bleeding without a trade-off in efficacy. Our pilot study is the first to examine aspirin withdrawal directly after PCI for ACS without ST-segment elevation but was limited in sample size and did not include a control group. Ultimately, large-scale randomised controlled trials will need to confirm the efficacy and safety of direct P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy compared to 12 months of DAPT.

Acknowledgements

The investigators would like to thank Dr E.K. Arkenbout and Dr R.J. van der Schaaf for serving as members of the data and safety monitoring board.

Funding

The OPTICA pilot study was funded by the Amsterdam UMC (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and received in-kind contributions from Werfen (Barcelona, Spain) and Abbott Vascular (CA, USA).

Conflict of interest statement

M.A.M. Beijk received a research grant from Actelion (Johnson & Johnson). W.J. Kikkert received a research grant from AstraZeneca. Y. Appelman received a research grant from the Dutch Heart Foundation. J.P.S. Henriques received research grants from Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, B. Braun, Getinge, Ferrer, Infraredx, and ZonMw. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.