Abstract

Aims: The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of ticagrelor monotherapy after one-month dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) or conventional DAPT in patients with or without acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the GLOBAL LEADERS Adjudication Sub-StudY (GLASSY).

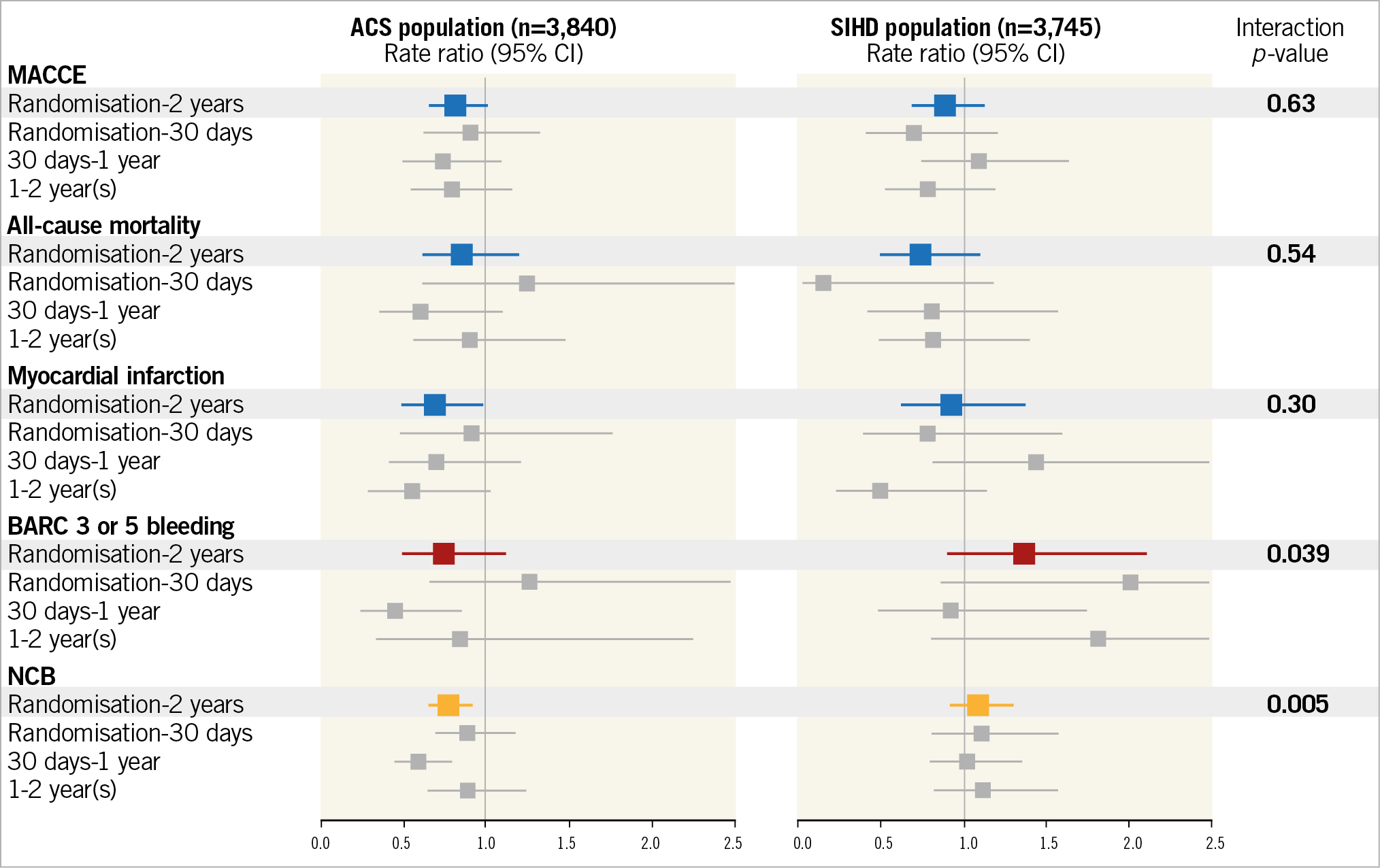

Methods and results: Risk estimates were expressed as rate ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A total of 3,840 ACS and 3,745 stable ischaemic heart disease (SIHD) patients were included. At two years, rates of the co-primary efficacy endpoint, a composite of death, myocardial infarction, stroke or urgent target vessel revascularisation, were 7.94% in the experimental and 9.68% in the control group (RR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.66-1.01) among ACS patients and 6.31% in the experimental and 7.14% in the control group (RR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.69-1.13) among SIHD patients (pint=0.63). Trends for lower and higher risk of BARC 3 or 5 bleeding with the experimental strategy in ACS (2.27% vs 3.00%, RR 0.76, 95% CI: 0.51-1.12) and SIHD (2.70% vs 1.96%, RR 1.39, 95% CI: 0.91-2.12) patients, respectively, were observed with significant interaction testing (pint=0.039). A net clinical benefit endpoint, the composite of both co-primary study endpoints, favoured the experimental treatment among ACS patients only.

Conclusions: Ticagrelor monotherapy after one-month DAPT provided consistent treatment effects on ischaemic endpoints in patients with or without ACS but only the former experienced a net clinical benefit. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03231059

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is the current standard of care in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)1. Because of their favourable risk-benefit ratio compared to clopidogrel, potent P2Y12 inhibitors in addition to aspirin are currently recommended for one year after PCI for acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Prolonged DAPT mitigates the recurrence of ischaemic events, in particular in patients with prior myocardial infarction (MI) and other high-risk clinical features2. However, it confers an increased risk of major bleeding with a relevant impact on mortality, morbidity and costs3.

Ticagrelor showed superior efficacy, including lower cardiovascular mortality rates, as compared to clopidogrel in patients with ACS but it increased spontaneous bleeding compared to clopidogrel4. Evidence regarding the risk/benefit profile of ticagrelor in patients with stable ischaemic heart disease (SIHD) is more limited.

In this study we explored the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor monotherapy from one month after PCI as compared to the current standard of care on adjudicated endpoints among 7,585 patients with or without ACS from the top 20 sites participating in the GLOBAL LEADERS trial (A Clinical Study Comparing Two Forms of Anti-platelet Therapy After Stent Implantation).

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

GLASSY (NCT03231059) was a pre-specified ancillary study of the GLOBAL LEADERS trial (NCT01813435)5. Details of the study participants and procedures are provided in Supplementary Appendix 1-Supplementary Appendix 6. Ethics committees from each participating institution approved the study protocol and the study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and of Good Clinical Practice.

STUDY ENDPOINTS

The co-primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of death, MI, stroke or urgent target vessel revascularisation. The co-primary safety endpoint was a composite of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) 3 or 5 bleeding events. Secondary endpoints included each component of the co-primary composite endpoints plus definite, probable or possible stent thrombosis according to the Academic Research Consortium (ARC) classification; bleeding events adjudicated according to BARC, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) and Global Utilisation of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Arteries (GUSTO) classifications; type of death (cardiovascular, non-cardiovascular). Endpoint definitions are reported in Supplementary Appendix 7.

An independent clinical events committee blinded to treatment allocation adjudicated all suspected endpoints based on previously described trigger logics embedded in the case report forms.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The co-primary efficacy and safety endpoints were the composite of death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, or urgent target vessel revascularisation (TVR) and type 3 or 5 BARC bleeding. A post hoc composite endpoint of net clinical benefit (NCB), defined as the composite of both co-primary study endpoints, consisting of all-cause death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, urgent TVR and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding was also considered. They were analysed by stratifying the population based on ACS versus SIHD, following the intention to treat with the Mantel-Cox method and reported as rate ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We also performed pre-specified landmark analyses with cut-offs at 30 days and one year after the index procedure, with RRs calculated separately for events up to and beyond the landmarks. Consistency of treatment effect was analysed with treatment-by-subgroup interaction testing by ACS or SIHD at presentation. Secondary endpoints were analysed by intention to treat with the Mantel-Cox log-rank method. Conventional level of significance (p=0.05) was used for all p-values.

There was no adjustment for multiple testing of secondary endpoints. Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test; continuous variables were compared with the Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed data. All analyses were performed at the Clinical Trials Unit (University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland) in Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

PATIENTS AND PROCEDURES

From July 2013 to November 2015, 3,840 patients with ACS (1,939 in the experimental arm and 1,901 in the control arm) and 3,745 patients with SIHD (1,855 in the experimental arm and 1,890 in the control arm) were included from 20 sites across 9 countries (Supplementary Figure 1). Baseline clinical and procedural features were balanced between arms within each presentation stratum (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2). Adherence to study medications is shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Outcomes

FATAL AND ISCHAEMIC ENDPOINTS

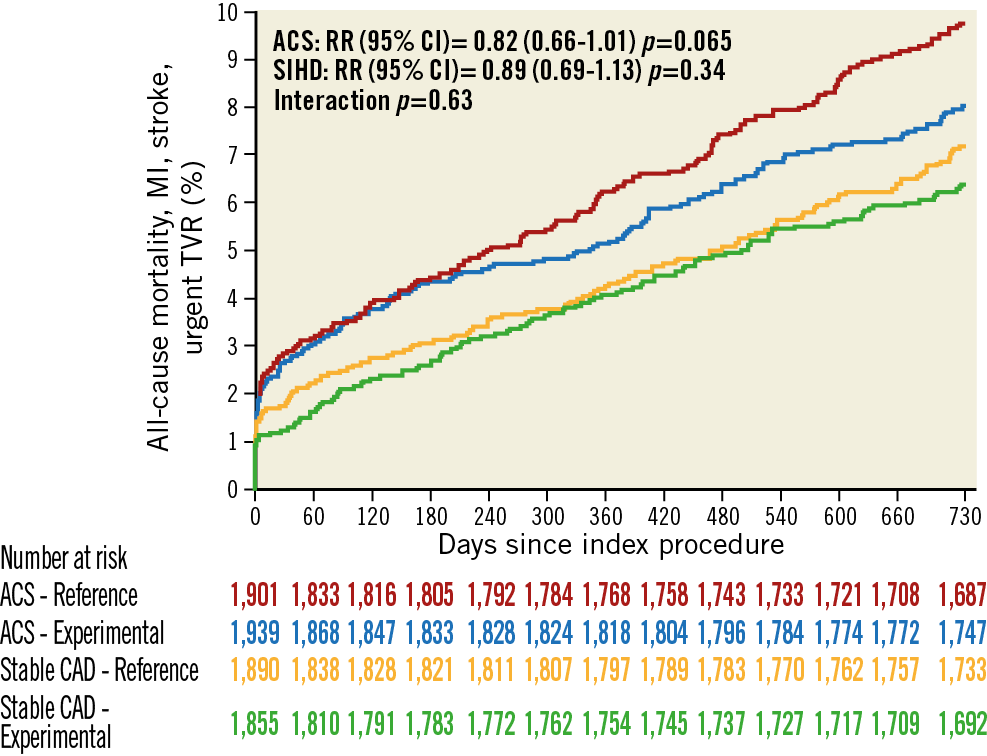

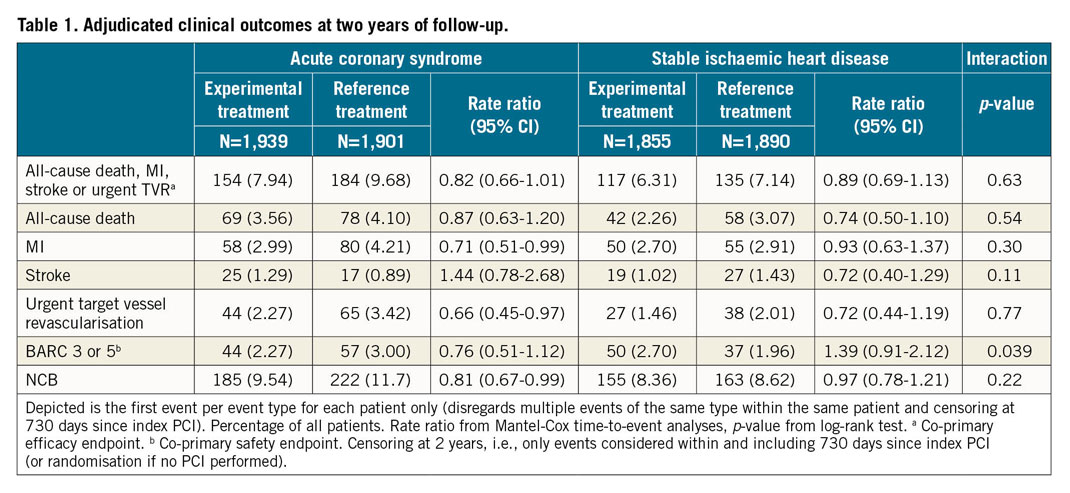

At two years, the co-primary efficacy endpoint occurred in 154 (7.94%) patients in the experimental arm and in 184 (9.68%) patients in the control arm (RR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.66 to 1.01; p=0.065) in the ACS group, and in 117 (6.31%) patients in the experimental arm and in 135 (7.14%) patients in the control arm (RR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.69 to 1.13; p=0.34) in the SIHD group, with non-significant interaction testing (pint=0.63) (Figure 1, Figure 2, Table 1).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier graphs for the co-primary ischaemic endpoint. Red lines, ACS patients in the reference arm; blue lines, ACS patients with experimental treatment; orange lines, SIHD patients in the reference arm; green lines, SIHD patients with experimental treatment.

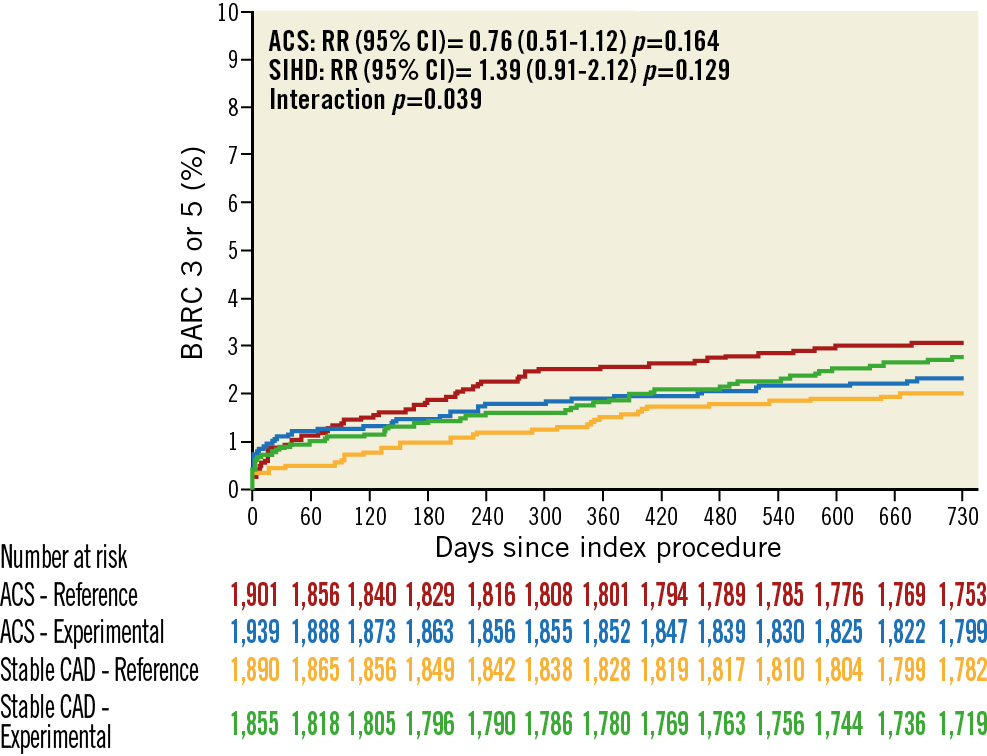

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates for the co-primary safety endpoint. Red lines, ACS patients in the reference arm; blue lines, ACS patients with experimental treatment; orange lines, SIHD patients in the reference arm; green lines, SIHD patients with experimental treatment.

A total of 69 (3.56%) patients in the experimental arm and 78 (4.10%) in the control arm (RR 0.87, 95% CI: 0.63 to 1.20; p=0.39) in the ACS group and 42 (2.26%) patients in the experimental arm and 58 (3.07%) patients in the control arm (RR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.50 to 1.10; p=0.14) in the SIHD group died within two years (pint=0.54) (Table 1, Figure 2).

The rates of MI (2.99% vs 4.21%, RR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.99; p=0.046) and urgent TVR (2.27% vs 3.42%, RR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.45 to 0.97; p=0.033) were significantly lower among ACS patients with experimental treatment whereas they did not differ among SIHD patients (2.70% vs 2.91% and 1.46% vs 2.01%, respectively). There was no evidence of interaction for either endpoint. Secondary endpoints are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

BLEEDING AND NET ADVERSE CLINICAL ENDPOINTS

Interaction testing for the occurrence of the co-primary safety endpoint of BARC grade 3 or 5 bleeding was significant (pint=0.039), with a lower risk in ACS (2.27% vs 3.00%, RR 0.76, 95% CI: 0.51 to 1.12; p=0.164) and a higher risk in SIHD (2.70% vs 1.96%, RR 1.39, 95% CI: 0.91 to 2.12; p=0.129) patients assigned to the experimental arm, respectively (Table 1, Figure 2, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Rate ratios of co-primary endpoints and other secondary efficacy or safety endpoints at two years and according to landmark analysis at 30 days, from 30 days to one year and beyond one year. Blue, RR and corresponding 95% CI of efficacy endpoints from randomisation to two years. Red, RR and corresponding 95% CI of BARC 3 or 5 bleeding from randomisation to two years. Orange, RR and corresponding 95% CI of NCB from randomisation to two years. Grey, landmark analyses.

BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding occurred in 147 (7.58%) patients in the experimental arm and in 186 (9.78%) patients in the control arm (RR 0.77, 95% CI: 0.62 to 0.95; p=0.017) in the ACS group and in 174 (9.38%) patients in the experimental arm and in 134 (7.09%) patients in the control arm (RR 1.34, 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.68; p=0.010) in the SIHD group, with significant treatment-by-subgroup interaction (pint<0.001) (Supplementary Table 3).

NCB occurred in 185 (9.54%) patients in the experimental arm and in 222 (11.7%) patients in the control arm (RR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.67 to 0.99; p=0.037) in the ACS group and in 155 (8.36%) patients in the experimental arm and in 163 (8.62%) patients in the control arm (RR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.78 to 1.21; p=0.815) in the SIHD group (pint=0.22) (Table 1). Other secondary endpoints are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

LANDMARK ANALYSES

Landmark analysis at 30 days suggested significant interaction according to clinical presentation with respect to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality that was similar in both treatment groups in ACS patients but seemingly lower with experimental therapy in SIHD patients. Some bleeding endpoints, including BARC 2 or 3, were increased with experimental therapy in SIHD but not in ACS patients (Supplementary Table 4).

Landmark analysis from 31 days to one year did not provide evidence of interaction for any of the fatal or ischaemic cardiovascular or cerebrovascular endpoints when stratified based on presenting syndrome, whereas there were strong signals for interaction for multiple bleeding endpoints, including BARC 2 or 3 as well as BARC 2, 3 or 5, owing to the lower risks with the experimental therapy in ACS patients counterbalanced by an opposite trend in SIHD patients (Supplementary Table 5).

Finally, there was no signal for interaction with respect to any ischaemic or bleeding endpoints at landmark analysis from one to two years.

Discussion

This subgroup analysis of centrally adjudicated efficacy and safety endpoints among patients of the GLASSY study presenting with ACS or SIHD showed the following:

1. Ticagrelor monotherapy after one-month DAPT (experimental strategy) provided consistent treatment effects in patients with ACS or SIHD in terms of a composite endpoint of ischaemic events compared to standard DAPT (reference strategy).

2. ACS but not SIHD patients (although with negative interaction testing) experienced nominally significant reductions of MI and urgent TVR at two years with the experimental strategy.

3. There were trends towards lower and higher risk of BARC 3 or 5 bleeding with the experimental strategy in ACS and SIHD patients, respectively.

4. A treatment-by-subgroup interaction was also noted for the composite of the co-primary efficacy endpoint and BARC grade 2, 3 or 5 bleeding with respect to clinical presentation, suggesting an NCB of the experimental strategy among ACS but not among SIHD patients.

Importantly, in GLASSY, randomisation to either the experimental or the reference strategy was stratified by clinical presentation at the index PCI.

Our analysis suggests that, in ACS but not in SIHD patients, ticagrelor monotherapy after one-month DAPT may represent an attractive option as compared to current guideline-recommended treatment.

The search for optimal antiplatelet therapy after PCI is currently focusing on lowering the risk of recurrent ischaemic events while avoiding bleeding. Evidence from the DAPT2 and PEGASUS6 trials supports the superior ischaemic protection of prolonged DAPT with aspirin and an oral P2Y12 inhibitor across the broad spectrum of coronary artery disease, with a more pronounced effect in post-MI patients. However, both studies identified a sizeable bleeding liability, including major albeit non-fatal bleeding, with prolonged DAPT. In the THEMIS study, a prolonged DAPT regimen consisting of aspirin and ticagrelor at 90 or 60 mg in SIHD patients with diabetes mellitus without a history of MI or stroke conveyed a reduced risk of ischaemic cardiovascular events compared to aspirin monotherapy; however, the incidence of major bleeding was higher with ticagrelor, yielding a lower number needed to treat for harm than for benefit7,8.

A possible strategy to preserve ischaemic benefit in the early period while mitigating bleeding risk in the longer term was investigated in the TROPICAL-ACS trial in which a stepwise, platelet function testing-guided de-escalation from prasugrel to the less potent clopidogrel, at two weeks after discharge, was non-inferior to standard DAPT9.

Our current data indicate that ticagrelor monotherapy after one month of DAPT provides similar ischaemic protection, but fewer bleeding hazards, as compared to standard DAPT. The interpretation of our results is challenged by the parent study design: patients allocated to the experimental arm received aspirin and ticagrelor for 30 days irrespective of clinical presentation (as opposed to aspirin and ticagrelor in ACS patients and aspirin and clopidogrel in SIHD patients in the control group) followed by ticagrelor alone from day 31 to two years (as opposed to aspirin and ticagrelor in ACS patients and aspirin and clopidogrel in SIHD patients in the control group from day 31 to one year, followed by aspirin monotherapy during the course of the second year). Therefore, the observed results might reflect the higher risk of bleeding associated with the combined use of ticagrelor and aspirin in stable patients assigned to the experimental arm.

The benefit of dropping aspirin in the experimental strategy was more evident among ACS patients who received more profound and consistent P2Y12 inhibition with ticagrelor on top of aspirin. At landmark analysis, the benefit in terms of BARC grade 3 or 5 bleeding with the experimental as opposed to the control arm was greatest from 31 to 365 days. On the other hand, the prevention of MI with the experimental strategy was highest beyond 365 days when both ACS and SIHD patients who were randomised to the experimental arm received ticagrelor instead of aspirin monotherapy.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of the recent double-blind Ticagrelor with Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients after Coronary Intervention (TWILIGHT) trial, which showed, especially in ACS patients, a remarkable bleeding reduction with ticagrelor monotherapy as compared to aspirin and ticagrelor in PCI patients after a course of three-month DAPT10. Consistent results were also recently reported by the ShorT and Optimal Duration of Dual AntiPlatelet Therapy-2 Study (STOPDAPT-2)11 and by the Smart Angioplasty Research Team: Comparison Between P2Y12 Antagonist Monotherapy vs Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients Undergoing Implantation of Coronary Drug-Eluting Stents (SMART-CHOICE) trial12, which showed that a P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy, after either one- or three-month DAPT, preserved ischaemic risks but lowered the bleeding hazard as compared to standard DAPT. The present analysis lends additional support to the hypothesis that dropping the less effective antiplatelet agent (aspirin) rather than combining more antiplatelet agents in patients undergoing PCI confers a better safety profile in terms of bleeding, with a similar or better protection against ischaemic events.

Limitations

First, we included consecutive patients from the highest enrolling sites rather than a randomly selected sample from all sites of the parent trial. Nevertheless, we have already shown that there was no evidence for treatment-by-subgroup interaction for the primary study outcome or other key secondary efficacy or safety endpoints between GLASSY and non-GLASSY sites. Second, adherence to allocated treatment was significantly lower in the experimental arm. Nevertheless, discontinuation rates were comparable to other trials investigating ticagrelor. Third, one-year DAPT in the control group across all SIHD and ACS patients may no longer be perceived as the current standard of care. Fourth, the observed interaction for the type of reference treatment might reflect the higher risk of bleeding associated with the combined use of ticagrelor and aspirin in stable patients in the experimental arm. Fifth, the study had an open-label design and event rates for ischaemic and bleeding endpoints were lower than anticipated, with a consequent impact on the nominal power for the tested hypothesis.

Conclusions

Ticagrelor monotherapy after one-month DAPT, as compared to one-year DAPT followed by aspirin alone, provided consistent ischaemic protection both in patients with and in those without ACS at 24 months. There was, however, evidence for differences in treatment effect for safety with respect to presenting syndrome, such that only patients with ACS derived a bleeding benefit with ticagrelor monotherapy after 12-month DAPT as compared to conventional treatment.

|

Impact on daily practice In patients undergoing PCI with new-generation drug-eluting stents, ticagrelor monotherapy after one month of DAPT provides consistent treatment benefit in patients with and in those without ACS as compared to standard therapy with regard to ischaemic events; however, only patients with ACS experienced a bleeding risk reduction and a favourable net clinical benefit with this strategy. |

Appendix. Study collaborators

Edouard Benit, MD; Jessa Hospital, Department of Cardiology, Hasselt, Belgium. Christoph Liebetrau, MD; Department of Cardiology, Kerckhoff Heart and Thorax Center, Bad Nauheim, Germany and German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), partner site RheinMain, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Luc Janssens, MD; Imelda Hospital, Bonheiden, Belgium. Maurizio Ferrario, MD; University of Pavia and Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico S. Matteo, Pavia, Italy. Aleksander Zurakowski, MD; Center of Cardiovascular Research and Development, American Heart of Poland, Katowice, Poland. Roberto Diletti, MD, PhD; Thoraxcenter, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Marcello Dominici, MD, S. Maria University-Hospital, Terni, Italy. Kurt Huber, MD; 3rd Medical Department, Cardiology, Wilhelminen Hospital, and Sigmund Freud University Medical School, Vienna, Austria. Ton Slagboom, MD; OLVG Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Paweł Buszman, MD; Center for Cardiovascular Research and Development, American Heart of Poland, Katowice, Poland. Leonardo Bolognese, MD; Azienda Usl Toscana Sud Est, Arezzo, Italy. Carlo Tumscitz, MD; Cardiology Unit, Sant’Anna Hospital, Ferrara, Italy. Krzysztof Bryniarski, MD, PhD; Jagiellonian University Medical College, The John Paul II Hospital, Krakow, Poland. Adel Aminian, MD; Department of Cardiology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Charleroi, Charleroi, Belgium. Mathias Vrolix, MD; Ziekenhuis Oost Limburg, Genk, Belgium. Ivo Petrov, MD; Acibadem City Clinic Cardiovascular Center, Sofia, Bulgaria. Scot Garg, MD, PhD; East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust, Blackburn, United Kingdom. Christoph Naber, MD; Contilia Heart and Vascular Centre, Stadtspital Triemli Zürich, Switzerland. Janusz Prokopczuk, MD; PAKS, Kedzierezyn-Kozle, Poland.

Funding

The study was funded by the University of Bern, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland.

Conflict of interest statement

S. Leonardi reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, and BMS/Pfizer, outside the submitted work. P. Vranckx reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Bayer AG, CLS Behring, and Medscape, outside the submitted work. P.W. Serruys reports personal fees from Abbott, Biosensors, Cardialysis, Medtronic, Sino Medical Sciences, Philips/Volcano, Xeltis, and HeartFlow, outside the submitted work, and personal consultancy fees from Abbott Laboratories, Biosensors, Cardialysis, Medtronic, Sino Medical Sciences Technology, Philips/Volcano, Xeltis, and HeartFlow. G. Steg reports grants and personal fees from Bayer/Janssen, Merck, Sanofi, Amarin, and Servier, personal fees from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, Novartis, Regeneron, Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Idorsia, outside the submitted work. D. Heg is affiliated with CTU Bern, University of Bern, which has a staff policy of not accepting honoraria or consultancy fees. However, CTU Bern is involved in design, conduct, or analysis of clinical studies funded by not-for-profit and for-profit organisations. In particular, pharmaceutical and medical device companies provide direct funding to some of these studies. S. Windecker reports grants from Amgen, Abbott, Bayer, BMS, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, CSL Behring, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Polares, and SINOMED, outside the submitted work. P. Jüni serves as unpaid member of the steering group of trials funded by AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Biosensors, St. Jude Medical and The Medicines Company, and has participated in advisory boards and/or consulting from Amgen, Ava and Fresenius, but has not received personal payments by any pharmaceutical company or device manufacturer. M. Valgimigli reports grants and personal fees from Terumo, personal fees from AstraZeneca, Alvimedica/CID, Abbott Vascular, Daiichi Sankyo, Opsens, Bayer, CoreFlow, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Universität Basel / Dept. Klinische Forschung, Vifor, Bristol Myers Squibb SA, iVascular, and Medscape, outside the submitted work. C. Liebetrau reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. R. Diletti reports grants from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. C. Naber reports personal fees from Abbott, Medtronic, Bionsesors, and Biotronik, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.