Abstract

Aims: In patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), the risk of ischaemic complications is highest in the early phase (during the first 30 days), while most bleeding events occur predominantly during the maintenance phase of treatment (after the first 30 days). Data on the de-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy by switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilised AMI patients are limited. The aim of this study is to investigate the efficacy and safety of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in AMI patients with no adverse event during the first month after the index PCI with newer-generation DES.

Methods and results: TALOS-AMI is a multicentre, randomised, open-label study enrolling 2,590 AMI patients with no adverse events during the first month after the index PCI. One month after the index PCI, eligible patients are randomly assigned either to 1) aspirin 100 mg plus clopidogrel 75 mg daily, or to 2) aspirin 100 mg plus ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, in a 1:1 ratio. The primary endpoint is a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, and bleeding type 2, 3 or 5 according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria from 1 to 12 months after the index PCI.

Conclusions: The TALOS-AMI trial is the first large-scale, multicentre, randomised study exploring the efficacy and safety of the de-escalation of antiplatelet therapy by switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilised AMI patients undergoing PCI.

Introduction

Since potent P2Y12 inhibitors, ticagrelor and prasugrel, significantly reduced ischaemic events compared to clopidogrel in two pivotal, large-scale clinical trials1,2, patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are strongly recommended to take potent P2Y12 inhibitors preferentially over clopidogrel for one year3.

However, along with strong antiplatelet efficacy, a higher risk for bleeding was observed for potent P2Y12 inhibitors compared with clopidogrel in these randomised trials. Intriguingly, benefit due to reduction of ischaemic events and harm due to bleeding events predominate at different time points during potent P2Y12 inhibitor treatment4. Although the ischaemic benefit was consistent throughout the first year after the index event, the benefit of ticagrelor and prasugrel over clopidogrel for reducing thrombotic risk was prominent in the early period after acute coronary syndrome (ACS) when the risk of ischaemic complications was highest5,6. On the other hand, landmark analyses of these two randomised trials revealed that the bleeding risk was similar in the early period of treatment, but there was a larger difference during the chronic period of treatment between potent P2Y12 inhibitors and clopidogrel. Actually, most bleeding events occurred predominantly during the maintenance period of treatment7,8. As a consequence, to optimise net clinical benefit between early ischaemic benefit and late bleeding risks in AMI patients, the strategy of de-escalating dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) by employing potent P2Y12 inhibitors mainly in the acute phase of treatment (during the first 30 days) and using the less potent clopidogrel during the maintenance phase of treatment (after the first 30 days) has gradually emerged as an important subject.

Despite evidence for the consistent efficacy and safety of potent P2Y12 inhibitors with long-term treatment, de-escalation after ACS is quite common in clinical practice9,10,11. Data have shown that the prevalence of de-escalation during hospitalisation ranges from 5% to 14%10, and after discharge ranges from 15% to 28%11. However, data from large-scale, well-designed, clinical studies on the de-escalation of DAPT by switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilised AMI patients are limited, and the results of studies are conflicting at present9,12. The TOPIC (Timing of Optimal Platelet Inhibition After Acute Coronary Syndrome) trial is the only randomised trial to test this hypothesis. However, it has many intrinsic weaknesses - single-centre study, use of a sealed-envelope random system, self-reported bleeding episodes and treatment discontinuation and, more importantly, limited sample size12. In addition, there are no studies on the de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment enrolling only AMI patients treated by PCI with the use of newer-generation drug-eluting stents (DES). In the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) study, only 60% of the population were scheduled for PCI and the patients who underwent PCI received older-generation DES.

Therefore, we sought to investigate the efficacy and safety of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in AMI patients with no adverse event during the first month after the index PCI with newer-generation DES.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

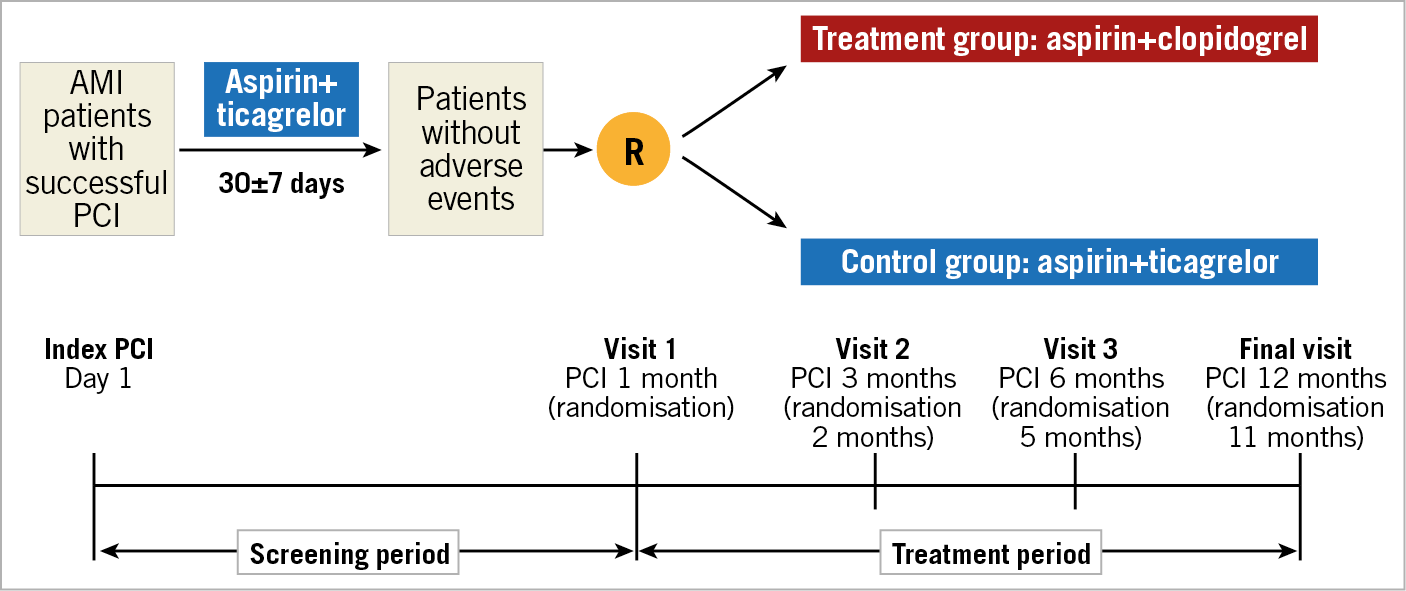

The TALOS-AMI trial (TicAgrelor Versus CLOpidogrel in Stabilized Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT 02018055) is a phase IV prospective, multicentre, randomised, open-label parallel group trial to compare the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel versus ticagrelor in approximately 2,600 stabilised patients with AMI after PCI. The study flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flow chart. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; R: randomisation

STUDY POPULATION

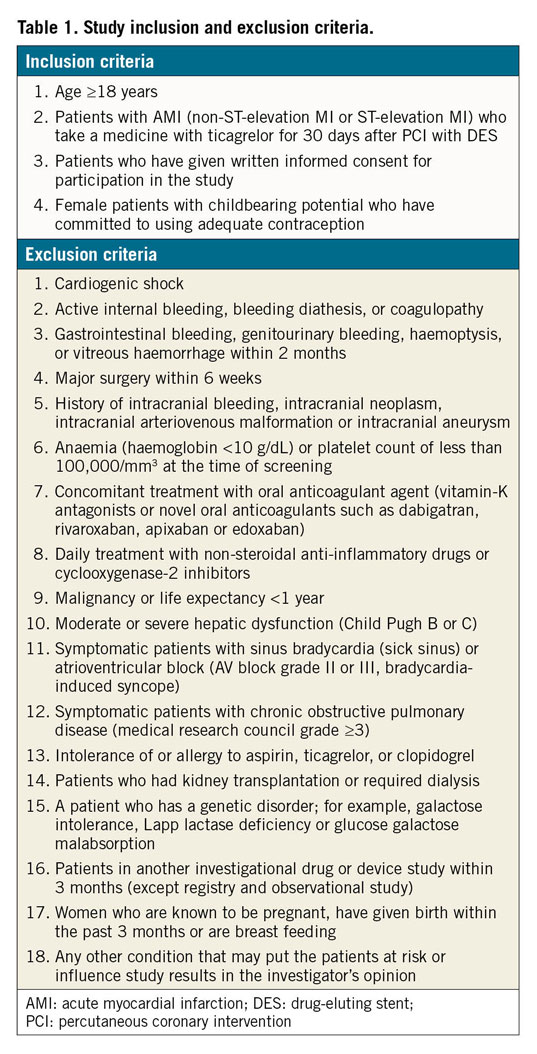

The primary enrolment criteria are as follows: patients with biomarker-positive AMI (non-ST-segment elevation or ST-segment elevation MI) undergoing PCI with DES, treatment with aspirin and ticagrelor for one month after the index PCI, no major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) during one month after the index PCI and age ≥18 years old. The definition of AMI is based on the third universal definition of myocardial infarction13. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. In order to investigate the possibility of selection bias during enrolment and to investigate the effects of enrolment criteria on recruitment, the screening logs of all patients who are eligible or not eligible for this study will be collected from each site.

RANDOMISATION AND FOLLOW-UP

Before PCI, a 250-325 mg loading dose of aspirin is given to patients who are naïve to treatment and all patients receive a loading dose of ticagrelor 180 mg. Discharge medication consists of aspirin 100 mg once and ticagrelor 90 mg twice per day. All patients receive treatment with aspirin plus ticagrelor for one month after the index PCI (screening period) (Figure 1). At 30±7 days after the index PCI, eligible patients are randomly assigned either to 1) aspirin 100 mg plus clopidogrel 75 mg daily (treatment group), or to 2) aspirin 100 mg plus ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily (control group), in a 1:1 ratio. The randomisation sequence will be created by an independent statistician using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and will be stratified by study centre and type of AMI (STEMI or NSTEMI) with a 1:1 allocation using hidden random block size. At one month after the index PCI, subjects meeting the eligibility criteria are assigned to a study treatment group following access to the interactive web-based response system (IWRS; Medical Excellence Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea). In the treatment group, when switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel, patients take 75 mg clopidogrel without a loading dose at the time of the next scheduled dose after the final dose of ticagrelor (e.g., ≈12 hours from last dose of ticagrelor). The monitoring process for the safety issue of switching protocol from ticagrelor to clopidogrel is detailed in Supplementary Appendix 1. After randomisation, patients continue the same medication for 11 months according to their group allocation (treatment period) (Figure 1). Patients will be evaluated at 3 (2 months after randomisation), 6 (5 months after randomisation), and 12 (11 months after randomisation) months after the index PCI and will be monitored for the occurrence of clinical events. The investigators will follow the patients, by office visits (preferred) or by telephone contact, as necessary.

STUDY ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoint is a combination of the ischaemic and bleeding endpoints (net clinical benefit), which is a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death, MI, stroke (ischaemic, haemorrhagic, or unknown aetiology), and bleeding type 2, 3 or 5 according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria from 1 to 12 months after the index PCI14. Main secondary endpoints include 1) a composite of BARC bleeding type 2, 3 or 5, 2) a composite of CV death, MI, stroke or BARC bleeding type 3 or 5, and 3) a composite of CV death, MI or stroke between 1 and 12 months after the index PCI. Detailed definitions of all outcomes are provided in Supplementary Appendix 2.

GENETIC TESTING

We will perform genotyping associated with the pharmacogenetics of clopidogrel and ticagrelor (CYP2C19, CYP2B6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, P2RY12, ABCB1, PON-1) and genetic exploration related to the occurrence of MI using single-base extension methods15 in patients who sign an additional written informed consent independent of consent to participate in the main study. The role of genetic testing is not for decision making in the current study protocol but for a future genetic substudy. A blood sample will be collected during or shortly after the PCI procedure. The genetic testing will be performed in the central lab. A 6 to 10 mL sample is collected and mixed well in a Vacutainer® tube (Becton, Dickinson and Company [BD], Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). This is separated and kept in BD Falcon™ tubes in a −80°C freezer. Collected samples are moved to a central lab every six months or regularly. The storage period is five years from the day of transport and afterwards they are disposed of.

STATISTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

SAMPLE SIZE CALCULATIONS

The present study is designed to show non-inferiority for the treatment group with aspirin plus clopidogrel versus the control group with aspirin plus ticagrelor. The sample size is based on the combined occurrence rate of ischaemic and bleeding events between 1 and 12 months after AMI. According to the PLATO investigators, the event rate of the primary efficacy endpoint including CV death, MI or stroke was 5.28% in the ticagrelor group and 6.60% in the clopidogrel group between 1 and 12 months after the index event1. There were no reported data on the bleeding event rate associated with ticagrelor from 1 to 12 months after AMI, especially the BARC bleeding rate at the time of the present study design. Therefore, we assumed the event rate of BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding from the event rates of non-coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)-related PLATO major or minor bleeding because the content of BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding was conceptually quite similar with non-CABG-related PLATO major or minor bleeding. With regard to the assumption of the bleeding rate from 1 to 12 months after the index PCI, we calculated the expected bleeding rate using a proportional equation under the assumption that the occurrence ratio of non-CABG-related major bleeding of the first 30 days to that of after 30 days and the ratio of non-CABG-related major or minor bleeding of the first 30 days to that of after 30 days could be equal. Thus, for the event rate of BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding associated with ticagrelor from 1 to 12 months after AMI, the event rate was assumed from the event rates of non-CABG-related PLATO major or minor bleeding during a year of ticagrelor therapy (8.7%) and non-CABG-related major bleeding of the first 30 days (2.47%) and after 30 days (2.17%) in the PLATO trial. For the event rate of BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding associated with clopidogrel from 1 to 12 months after AMI, the event rate was assumed from the event rates of non-CABG-related PLATO major or minor bleeding during a year of clopidogrel therapy (7.0%) and non-CABG-related major bleeding of the first 30 days (2.21%) and after 30 days (1.65%) in the clopidogrel group of the PLATO trial7. After applying a proportional equation (Supplementary Appendix 3), we estimated that the BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding would be 4.07% in the ticagrelor group and 2.99% in the clopidogrel group. Thus, the expected event rate of the primary endpoint from 1 to 12 months after the index PCI was 9.35% (ischaemic event of 5.28% + bleeding event of 4.07%) in the ticagrelor group and 9.59% (ischaemic event of 6.6% + bleeding event of 2.99%) in the clopidogrel group.

We chose the non-inferiority margin in accordance with clinical judgement and other relevant studies with a non-inferiority design for the present study design. The non-inferiority margin of two contemporary trials of antiplatelet treatment after PCI that were available up to that time was equivalent to a 40% increase in the expected event rate16,17. The steering committee decided that the non-inferiority margin in our study should be less than a 40% increase compared to the expected event rate of the control group. After considering clinically acceptable relevance and the feasibility of study recruitment, we finally selected the non-inferiority margin of 3.0%, which was equivalent to a 32% increase in the expected event rate. Sample size calculations (PASS 13; NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA) were initially performed based on a one-sided α of 0.025 and a power of 80%. To achieve these goals, a total of 2,230 patients was needed. After considering a follow-up loss rate of 10%, there should be at least 1,644 per group and a total of 3,288 patients (Supplementary Appendix 4).

However, while the study was actively underway, the government policy on investigator-initiated trials (ITTs) changed: it was decided not to allow national health insurance to charge for the medical care costs of participating patients in ITTs. Soon after, the government was forced to permit the application of national health insurance to ITTs on the condition that researchers should obtain approval for their studies by the head of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment service. However, during this turmoil, researchers’ willingness to register patients had been compromised, and they could not register patients as planned within the period. Thus, the steering committee held an emergency meeting with data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) members and independent statisticians and decided to recalculate the sample size for the timely completion of the trial. In recalculating the sample size, we adopted a one-sided α of 0.05 instead of 0.025. According to the CONSORT statement of non-inferiority and equivalence in trials18, a one-sided α of 0.05 was acceptable for the non-inferiority clinical trials. Moreover, in the large-scale TROPICAL-ACS (Testing Responsiveness to Platelet Inhibition Chronic Antiplatelet Treatment for ACS) trial (one of the famous CV drug trials similar to the TALOS-AMI trial), the researchers adopted a one-sided α of 0.05 for the sample size calculation4. Furthermore, of 110 CV non-inferiority trials published in JAMA, The Lancet or the New England Journal of Medicine from 1990 to 2016, a one-sided α was 0.05 in 66 trials19. Based on this external harsh environment and a review of the sample size calculation in previous large-scale randomised trials published in high-impact journals, we recalculated the sample size by using a one-sided α of 0.05, a power of 80% and a follow-up loss rate of 10%. As such, the sample size was reduced from 3,288 to 2,590 (1,295 patients in each group) (Supplementary Appendix 5).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Primary analyses will be performed on an intention-to-treat basis. In addition, per-protocol analyses will be performed. Continuous variables will be presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) and compared using the Student’s t-test. Categorical variables will be presented as frequencies (percentage) and compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. The cumulative event rates for the primary endpoint will be estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank tests. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) will be calculated with Cox hazards regression analysis. If the upper limit of the one-sided 95% CI of the absolute difference is less than the pre-specified non-inferiority margin, clopidogrel treatment will be considered to be non-inferior to ticagrelor treatment. The analysis will be performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

PRESENT STATUS

The TALOS-AMI study is currently ongoing. The first patient was enrolled in February 2014 and the last patient was enrolled in December 2018. A total of 2,697 patients were enrolled, and the follow-up of the last patient was completed at the end of December 2019. A total of 32 major cardiac centres in Korea which perform high-volume PCI (>500 PCI/year) and are located throughout the country have participated in the present study. The DSMB reviewed the safety data after enrolment of 1,500 patients (57.9% of total enrolment) and recommended continuation of enrolment without protocol alterations. The number of patients initially planned to be enrolled was 2,590; however, the actual number of registered patients was greater than this (2,697). The randomisation of the current trial was performed using an interactive web-based response system and patients were competitively enrolled in 32 institutions. Despite the competitive registration among participating institutions, the random system did not have a lock on it, resulting in registration of 107 more patients than the initially planned number. When the DSMB closely monitored the status of additionally registered subjects, its members agreed that there were no safety issues and they obtained approval from the institutional review board (IRB) for using the data of additionally registered patients for the statistical analyses.

Clinical follow-up was performed by office visits or by telephone contact. The proportion of the two methods at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after the index PCI was as follows: 84.7%/16.3%; 78.4%/21.6%; 83.6%/16.4%, respectively.

Discussion

The primary and major secondary endpoints will be analysed in pre-specified subgroups to evaluate the consistency of results among subgroups of interest. Outcomes will be evaluated in the following subgroups: STEMI versus NSTEMI; implanted stent type; diabetes mellitus; age (≥ vs < median and ≥ vs <75 years); gender; chronic kidney disease, defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/m²; high bleeding risk versus low bleeding risk according to the ARC criteria20; CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele carrier versus non-carrier; left ventricular ejection fraction (≥ vs < median and ≥ vs <40%) (Supplementary Appendix 6).

Limitations

We estimated the BARC bleeding rate using PLATO bleeding. Thus, the estimated bleeding rate may be different from the actual event rate.

>Conclusions

The TALOS-AMI study is a prospective, multicentre, randomised, open-label trial to compare the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel versus ticagrelor in stabilised AMI patients after PCI. We expect that this study will provide a clearer answer regarding the net clinical benefit of a de-escalation strategy of P2Y12 inhibitors in AMI patients.

|

Impact on daily practice The TALOS-AMI trial tests the efficacy and safety of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilised AMI patients with no adverse event during the first month after the index PCI. Although current guidelines strongly recommend potent P2Y12 inhibitors for one year in AMI patients undergoing PCI, de-escalation after the index PCI is not uncommon in real-world clinical settings. However, data from well-powered randomised controlled trials are very limited. When the primary endpoint is met and the trial shows that the treatment group (aspirin plus clopidogrel) is non-inferior to the control group (aspirin plus ticagrelor), this study can provide strong evidence that switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilised AMI patients at one month after the index PCI is a clinically safe and efficacious strategy to optimise the balance between the early ischaemic benefit and late bleeding risk of potent P2Y12 inhibitors. |

Funding

This trial is supported by grants from Chong Kun Dang (Pharmaceutical Corporation. Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.