The old adage “time is muscle” has, for the last 30 years, been the guide for treatment strategies in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). A timely reperfusion is, in fact, key to the survival of cardiac cells and therefore to decreasing the risk of mechanical and arrhythmic complications. In the era of primary PCI, a great effort has been made to minimise the time span between first medical contact and target vessel reopening. This has involved the creation of operative networks and dedicated facilities aimed at optimising the clinical management of patients with STEMI. However, in real practice, the ischaemic time of these patients is still highly variable and often exceeds the recommended delay from symptom onset to coronary reperfusion1. In this context, achieving an effective platelet inhibition as early as possible seems a reasonable means of facilitating reperfusion and reducing the risk of recurrent thrombotic complications after PCI. Early administration of oral P2Y12 inhibitors seems even more desirable in STEMI patients, as drug absorption can be slowed down by unfavourable haemodynamic conditions and drug-drug interactions (e.g., with morphine)2, and platelet activation is increased and sustained by the inflammatory process3. Moreover, the degree of platelet reactivity before primary PCI has been shown to be a strong determinant of subsequent adverse events, including mortality3. On the other hand, administering antiplatelet drugs before knowing the coronary anatomy could lead to an overtreatment of those patients who will not ultimately undergo stenting, potentially exposing them to an increased bleeding risk, especially in cases where bypass graft surgery is indicated. However, these cases are rare and less than 2% of patients receiving a diagnosis of STEMI need surgery, versus 10% being treated medically and approximately 90% receiving primary PCI4.

Despite the biological rationale for pretreatment with P2Y12 inhibitors in STEMI, the evidence supporting this practice is not so convincing. In fact, with the exception of PCI CLARITY5, all other randomised studies comparing early vs. delayed administration of P2Y12 inhibitors have failed to demonstrate any substantial difference in clinical outcomes between the two strategies4,6,7. The reasons for these negative results might be found in small sample size6,7, frequent use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI)7, or the short time interval between pretreatment and PCI4. As a consequence of the uncertainty regarding the optimal timing of treatment with P2Y12 inhibitors in STEMI, current European guidelines recommend administering these drugs generically before PCI, or at the latest at the time of the procedure1.

In this issue of EuroIntervention, Bellemain-Appaix et al8 present a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised studies dealing with this topic.

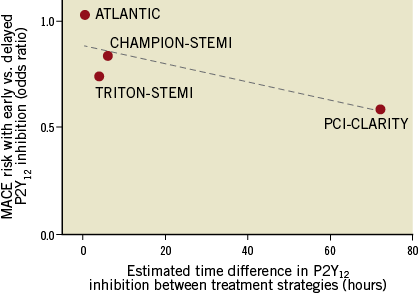

The authors, however, go beyond the mere comparison of different timings of antiplatelet treatment, but rather try to focus on the key issue, which is the timing of platelet inhibition. In fact, they also included in the analysis studies comparing drugs administered at the same time, but with different onset and intensity of action, therefore achieving diverse effects in terms of platelet inhibition (i.e., clopidogrel vs. prasugrel, clopidogrel vs. cangrelor). The meta-analysis showed that early vs. delayed platelet inhibition resulted in a significantly reduced risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), which was mainly driven by a lower incidence of recurrent myocardial infarction, but also led to an improved coronary flow before PCI, and less frequent bail-out use of GPI, with no significant difference in terms of bleeding risk. The authors should be commended for tackling this issue in a conceptually intriguing, but at the same time very practical fashion. While the inclusion of studies investigating the effects of several drugs, with very different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic features, might make it difficult to generalise the overall results, it should be interpreted as a “proof of concept”, in that the comparison is made between two strategies (i.e., early vs. delayed P2Y12 inhibition), independently of the drug used to achieve the goal. Nevertheless, the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution. In fact, the benefit of an early P2Y12 inhibition strategy seems no longer to hold true if we exclude from the analysis the old PCI CLARITY study, where the time interval between clopidogrel pretreatment and PCI was on average three days5. Moreover, the treatment strategy significantly interacts with the type of P2Y12 inhibitor and type of PCI in determining outcomes. Early P2Y12 inhibition seems to result in a larger benefit in studies of clopidogrel (vs. studies of new P2Y12 antagonists), and in secondary PCI (vs. primary PCI), proving once more the critical weight of PCI CLARITY in this analysis. In this perspective, one could argue that these results are outdated, as new P2Y12 inhibitors are now recommended in STEMI1. However, many patients are still treated with clopidogrel in real-world practice9, and this meta-analysis strongly supports the need for an early administration when using a slow-acting drug such as clopidogrel, in order to achieve as much platelet inhibition as possible at the time of PCI. Another key point emerging from this analysis is that there seems to be a correlation linking the time difference between early and delayed P2Y12 inhibition and the magnitude of the clinical benefit, i.e., the longer the interval, the greater the reduction of adverse events with an early strategy (Figure 1). Translating this into everyday practice, it seems reasonable to suppose that achieving early platelet inhibition would be even more beneficial when the delay to PCI is expected to be longer. Whether obtaining prompt platelet inhibition with faster and more potent P2Y12 inhibitors, using crushed pills or intravenous agents, could improve coronary flow and confer ischaemic protection at the time of PCI, even when ischaemic time is supposedly short, remains to be tested in dedicated clinical trials.

Figure 1. Time difference between early and delayed P2Y12 inhibition and magnitude of clinical benefit with an early strategy. Time was estimated based on pharmacodynamic data when different drugs were compared. Trials enrolling <1,000 patients were excluded.

Overall, and in line with current guidelines, this meta-analysis supports the practice of early P2Y12 inhibition in patients with STEMI, especially when long delays to PCI are expected, be it with a prompt administration of clopidogrel when this is the only pharmacological option, or using faster and more potent P2Y12 antagonists. However, the availability of many possible treatment strategies (i.e., different drugs, different administration modalities), which in time will increase, leaves room for individualised decisions based on patient- and environment-related variables (e.g., likelihood of STEMI diagnosis, haemodynamic conditions, expected ischaemic time, etc.). The goal is now set – the roads for getting there are many and yet to be explored.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.