In this issue of EuroIntervention Piriou et al1 present the logic and structure of the MITRA-HR prospective, multicentre, randomised trial.

This French trial, in a group of 330 high-risk surgical candidates with severe primary mitral regurgitation (MR), is designed to support the non-inferiority in efficacy and the superiority in safety of percutaneous mitral valve repair (PMVR) by means of the MitraClip® (MC) device (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) when compared to conventional reparative mitral valve (MV) surgery. The trial represents a real challenge for MC therapy. In fact, the community of French surgeons has historically shown its creativity and ability to manage primary MR by means of reparative techniques2.

Although we must praise the investigators for their commitment, we should not lose sight of our objective and critical spirit in trying to identify possible caveats that may lead, in the future, to a difficult interpretation of the MITRA-HR trial findings.

More specifically:

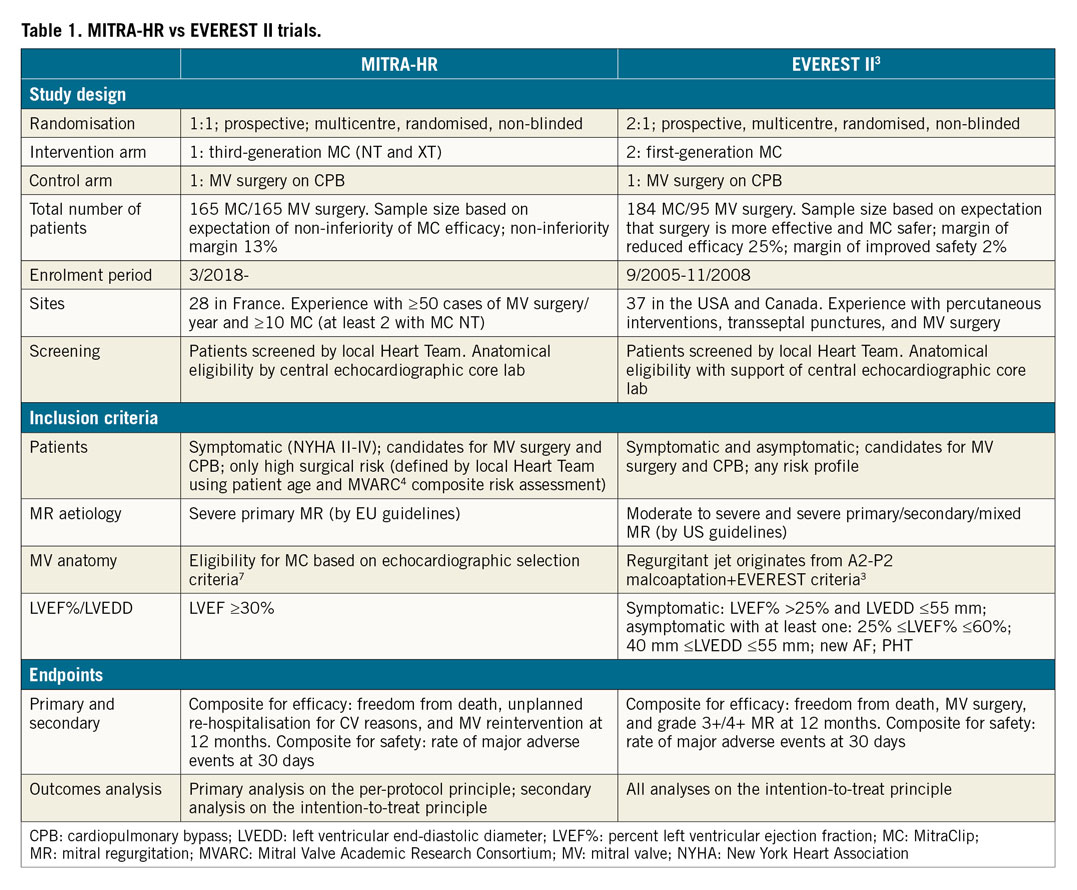

1) Since its introduction, percutaneous MV repair by means of the MC device has evolved significantly. Both device design and operator proficiency have improved. As a result, the structure of the MITRA-HR trial per se presents important differences when compared to previous MC trials such as EVEREST II3 (Table 1). At the beginning of the PMVR journey we were ready to accept the fact that MC therapy was less effective (mainly in terms of MR reduction) as long as its safety was superior to conventional surgery. The EVEREST II trial was sized and powered on these assumptions. Nowadays we should aim to demonstrate that MC technology is allowing us to treat patients with primary MR with surgical efficacy and improved safety, even when MR results from complex structural modifications of the native MV anatomy. In this contemporary context, the MITRA-HR study has undertaken this ambitious aim. If we accept the fact that it is now time to aim for equal efficacy between MC and surgery, we should stress the importance of factoring the degree of residual or recurrent MR into the equation. It should be emphasised that, differently from the EVEREST II trial, the MITRA-HR trial does not include MR grade 3+ or 4+ at 12 months within the composite primary endpoints; it focuses rather upon unplanned re-hospitalisation for cardiovascular reasons and MV reintervention at 12 months. Although the 2015 Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium (MVARC) document4 supports the fact that quantitative reduction in MR is a necessary condition for treatment effectiveness, it also states that MR is a surrogate endpoint that cannot serve as the primary effectiveness endpoint (either stand-alone or as a component of a composite measure). This is mainly based on the fact that MR reduction may not necessarily be associated with the patient’s clinical and functional improvement. In other words, there could be no clinical improvement even with a perfect MV repair. There is a possible logic to this statement when discussing secondary MR where progression of heart failure symptoms may continue as a result of myocardial contractility dysfunction and in spite of a reduction/correction of MR. Shall we extend the same logic to patients with primary MR where the reduction of MR should be the conditio sine qua non to define procedural efficacy? In fact, readmissions for cardiovascular reasons and reintervention on the MV may not necessarily occur even in the case of recurrent primary MR. This is particularly true if we focus on elderly patients with a low level of activity. In this context, it could well happen that the MITRA-HR trial will show us that the efficacy of MC therapy is similar to that of conventional surgery in spite of a significantly higher rate of recurrent MR. How shall we translate those findings to support the future management of younger and less comorbid patients for whom the consistent and durable reduction of MR will play a focal role in preventing non-reversible derangements of the cardiac function?

2) The MITRA-HR trial has been sized mainly on the basis of the non-inferiority of MC therapy in terms of the primary outcome (efficacy). When designing such a trial, the non-inferiority margin will determine the necessary patient sample size, given a pre-specified power (80%) and alpha risk (2.5%). The non-inferiority margin simply tells us how much difference in primary outcome we will comfortably accept. The higher the non-inferiority margins, the smaller the required sample size. Although the 13% non-inferiority margin for an expected primary outcome of 20% proposed in the MITRA-HR trial represents a step forward (the EVEREST II trial had a specified margin of reduced efficacy of MC therapy of 25% for the comparison of strategies), it could represent a future limitation in the correct interpretation of the primary endpoint. Although the proposed primary endpoint is a mixture of hard and soft outcomes, it still means that, if the primary outcome in the surgical cohort has an occurrence of 20%, the study will accept as statistically non-significantly different a primary outcome up to 33% in the MC therapy group. Of course, all this is done mainly with the aim of reducing the number of patients to be enrolled and the relative costs. Because the study is mainly based on French government academic funds, we believe that, in the future, extending the trial to high-volume recruiting European Union (EU) centres, and consequently gaining access to EU funds, may represent a logical evolution that could lead to a natural increase in patient enrolment.

3) Differently from the EVEREST II trial where all analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle, in the MITRA-HR trial the primary analysis is carried out on the per-protocol population; a secondary intention-to-treat analysis will be performed to show the consequences of patient exclusion. We believe that this will add to the controversy in the correct interpretation of findings. In light of the possible migration of patients after randomisation (high-risk patients who will be treated preferably with a minimally invasive percutaneous approach), imbalance between the two groups may occur. As a result, the per-protocol analysis will be inherently biased, because it violates the intention-to-treat principle. This questions the reason to design today a randomised trial if in the future the analysis will be performed outside of the randomisation criteria.

4) Patient inclusion criteria have a significant impact upon the outcomes of prospective trials. Recently, two MC therapy trials focusing on the treatment of secondary MR came to discordant conclusions, mainly based on the fact that they used different inclusion protocols and they treated patients at different stages of the pathology5,6. In the MITRA-HR study, a centralised core laboratory validates the patients’ echocardiographic eligibility for MC therapy which is based mainly on previously published echocardiographic selection criteria7. Within the proposed criteria, patients enrolled could present a large variation in MV degeneration, starting from a localised P2 prolapse and including multiple scallop prolapse and annular enlargement. In this context, the MITRA-HR trial has the goal of enrolling a “real-world population”. At the same time, it should be remarked that MC therapy outcomes in primary MR may change according to operator experience and to the complexity of MV pathology8. Primary MR may present a far greater challenge for inexperienced MC operators. The fact that, in the MITRA-HR trial, study centres with an experience of only 10 MC procedures can decide to treat even complex MV anatomies will add uncertainty to the data interpretation. Finally, the lack of a central eligibility committee, together with the limited sample size, could skew patient selection in some centres and result in single site outcomes, in either treatment arm, being outliers. All these will further complicate the outcomes analysis. In conclusion, outcomes will possibly change a lot in relation to the complexity of MV degenerative disease and to centre experience, particularly for the MC arm. Although limited by the sample size, sub-analyses will possibly lead to important observations in this sense.

5) The initial data of the MITRA-HR study will be limited to a 12-month follow-up. It is reasonable to believe that MC therapy will show a higher short-term safety when compared to conventional surgery in patients with primary MR and a high-risk profile. Moreover, MV surgery with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass will possibly lead to a greater acute reduction of MR but will also result in a systemic derangement of the organism of these highly comorbid patients. This impact may last for months after surgery and could, in theory, affect one-year mortality in the surgical arm. Once the “negative” impact of the surgical approach has lapsed, we will possibly start to realise if and how the quality of the MR correction will influence longer follow-up outcomes. A recent propensity-weighted analysis in elderly patients with primary MR has shown that patient survival after MC therapy drops significantly, in comparison to the surgical cohort, only after one year from the procedure. In this context, recurrence of MR is associated with an increased follow-up mortality8.

We believe that, beyond the 12-month follow-up milestone, the interesting part of the match will start and the MITRA-HR trial will give us a good initial basis to understand whether suboptimal correction of primary MR with MC is to be considered an acceptable compromise in those high-risk candidates who are referred to our practices daily.

In conclusion, we commend the MITRA-HR investigators highly for their courage; the race has actually already started and “meanwhile, magicians and astrologers gravitate around the circus, promising the unwary spectator to predict the name of the winning charioteer” (Marcus Tullius Cicero. De Divinatione. 44 B.C.).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.