Abstract

Aims: The aim of this study was to identify predictors of complete ST-segment resolution (STR) pre-primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients enrolled in the ATLANTIC trial.

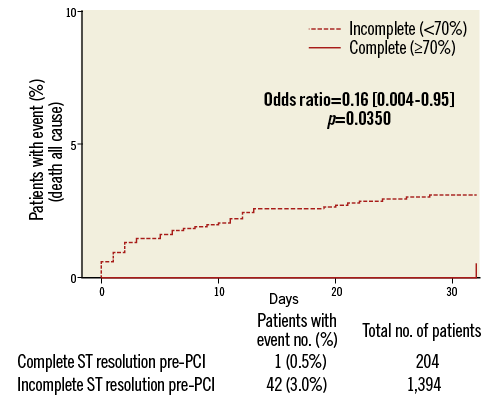

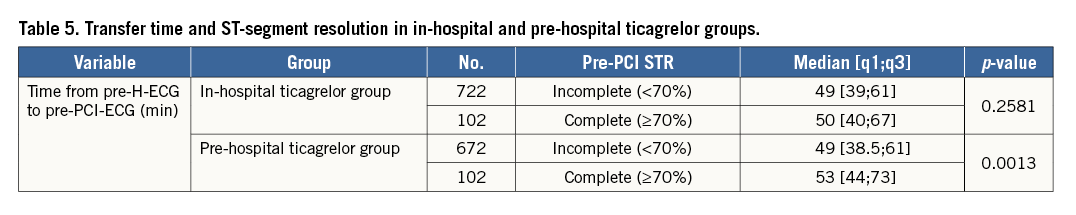

Methods and results: ECGs recorded at the time of inclusion (pre-hospital [pre-H]-ECG) and in the catheterisation laboratory before angiography (pre-PCI-ECG) were analysed by an independent core laboratory. Complete STR was defined as ≥70%. Complete STR occurred pre-PCI in 12.8% (204/1,598) of patients and predicted lower 30-day composite MACCE (OR=0.10, 95% CI: 0.002-0.57, p=0.001) and total mortality (OR=0.16, 95% CI: 0.004-0.95, p=0.035). Independent predictors of complete STR included the time from index event to pre-H-ECG (OR=0.94, 95% CI: 0.89-1.00, p=0.035), use of heparins before pre-PCI-ECG (OR=1.75, 95% CI: 1.25-2.45, p=0.001) and time from pre-H-ECG to pre-PCI-ECG (OR=1.09, 95% CI: 1.03-1.16, p=0.005). In the pre-H ticagrelor group, patients with complete STR had a significantly longer delay between pre-H-ECG and pre-PCI-ECG compared to patients without complete STR (median 53 [44-73] vs. 49 [38.5-61] mins, p=0.001); however, this was not observed in the control group (in-hospital ticagrelor) (50 [40-67] vs. 49 [39-61] mins, p=0.258).

Conclusions: Short patient delay, early administration of anticoagulant and ticagrelor if a long transfer delay is expected may help to achieve reperfusion prior to PCI. Pre-H treatment may be beneficial in patients with longer transfer delays, allowing the drug to become biologically active. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01347580.

Abbreviations

BMI: body mass index

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft

CI: confidence interval

GP: glycoprotein

MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events

OR: odds ratio

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

pre-H: pre-hospital

STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

STR: ST-segment elevation resolution

Introduction

In the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled ATLANTIC trial, pre-hospital (pre-H) administration of ticagrelor in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) appeared to be safe but did not improve pre-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) ST-segment elevation resolution (STR) and/or TIMI 3 flow in the culprit artery1. However, it is possible that the brief time interval from study drug administration in the ambulance to catheterisation laboratory (cathlab) may have limited the potential benefit of pre-H ticagrelor administration.

Since achievement of early myocardial reperfusion is one of the main goals in STEMI patients for improving prognosis, the identification of factors related to this objective may provide further insights into the optimisation of pre-hospital STEMI patient management. Therefore, we undertook an exploratory analysis describing the predictors, and clinical significance, of complete STR before PCI in STEMI patients enrolled in the ATLANTIC trial.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND PROCEDURES

The ATLANTIC trial was an international study that randomised patients presenting with ongoing STEMI to receive double-blind treatment with a 180 mg loading dose of ticagrelor either pre-H (in-ambulance) or in-hospital (in cathlab), in addition to aspirin and standard of care.

The trial design and main results have been published1,2. Briefly, eligible patients were identified by ambulance personnel for inclusion in the study following diagnosis of STEMI of more than 30 minutes’ but less than six hours’ duration, and with an expected time from qualifying ECG to first balloon inflation of less than 120 minutes. Randomisation and first loading dose of ticagrelor or matching placebo took place immediately after ECG confirmed the diagnosis of STEMI. Patients were then transferred to undergo coronary angiography and PCI, and the second loading dose was administered in the cathlab. All patients then received maintenance treatment with ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily for at least 30 days, up to a maximum of 12 months. In-ambulance use of glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitors was discouraged, but left to the physicians’ discretion.

ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS, DEFINITIONS AND ENDPOINTS USED

ST-segment analysis was performed on ECGs recorded pre-H (at the time of inclusion) and in the cathlab before angiography. The degree of STR was assessed by an independent core laboratory (eResearch Technology, Peterborough, United Kingdom), blinded to study treatment. The STR was calculated as the mean ST-segment elevation pre-H minus the mean ST-segment elevation pre-PCI divided by the mean ST-segment elevation pre-H and expressed as a percentage, i.e., STR=(ST pre-hospital–ST pre-PCI]/STpre-hospital)×100. Complete STR was defined as ≥70% STR.

Clinical endpoints, evaluated up to the date of the last study visit (≤32 days), included composite major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular clinical events (MACCE; defined as death, myocardial infarction, stroke or urgent revascularisation), definite stent thrombosis, and total mortality.

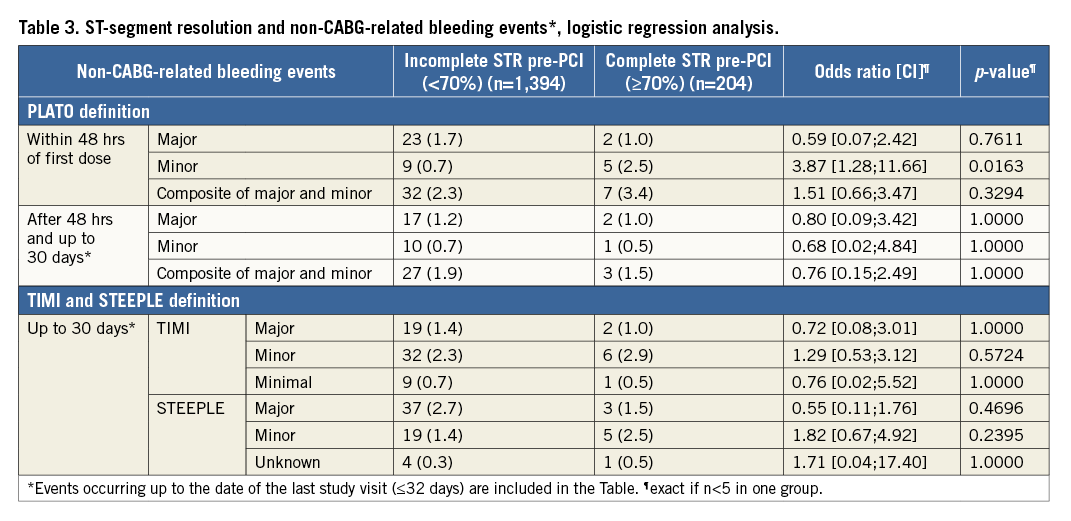

Safety endpoints analysed included major or minor bleeding (excluding coronary artery bypass graft [CABG]-related bleeding) within 48 hours of first dose and after 48 hours and up to the last study visit, using the Study of Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) definitions, or major, minor and minimal bleeding up to the last study visit, using TIMI, and Safety and Efficacy of Enoxaparin in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Patients (STEEPLE) definitions2. An independent adjudication committee conducted a blinded review of all clinical endpoints (except deaths and minimal bleeding events).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For continuous variables, mean, standard deviation and Student’s t-test p-value are presented in case of Gaussian distribution, or median, interquartile ranges, and Mann-Whitney’s p-value in case of non-Gaussian distribution. For categorical variables, number, percent and chi-square test p-value are presented, or Fisher’s test p-value is presented in case of low numbers of events.

Ischaemic endpoint analyses were performed in the modified intention-to-treat population, i.e., those patients who underwent randomisation received at least one dose of the study drug and had complete data for STR pre-PCI. For each endpoint, the two groups (complete STR group and incomplete STR group) were compared with the use of a logistic regression model. The 95% confidence intervals for the odds ratio were calculated and results were also presented as survival curves using Kaplan-Meier estimates.

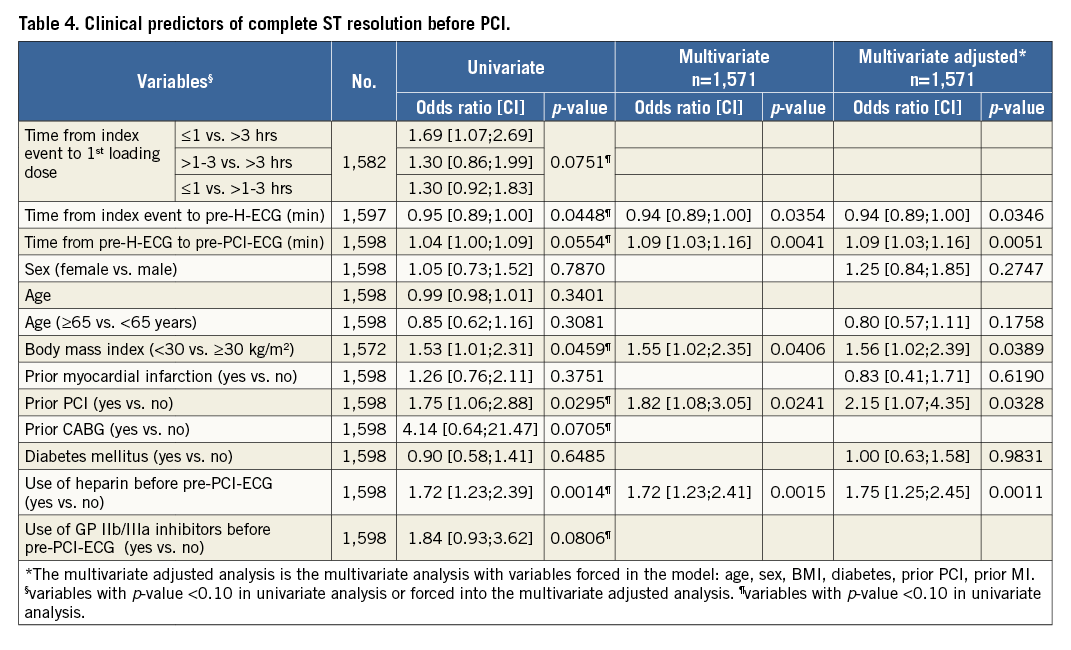

Potential predictors of complete STR before PCI were first identified as those variables with a p-value <0.10 in univariate analyses; these were then introduced in the multivariate analysis adjusted for baseline characteristics and major determinants of STR, including age, sex, body mass index, diabetes mellitus (DM), prior coronary intervention and prior MI, with a p-value <0.05 threshold for significance.

All tests had a two-sided significance level of 5% and were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

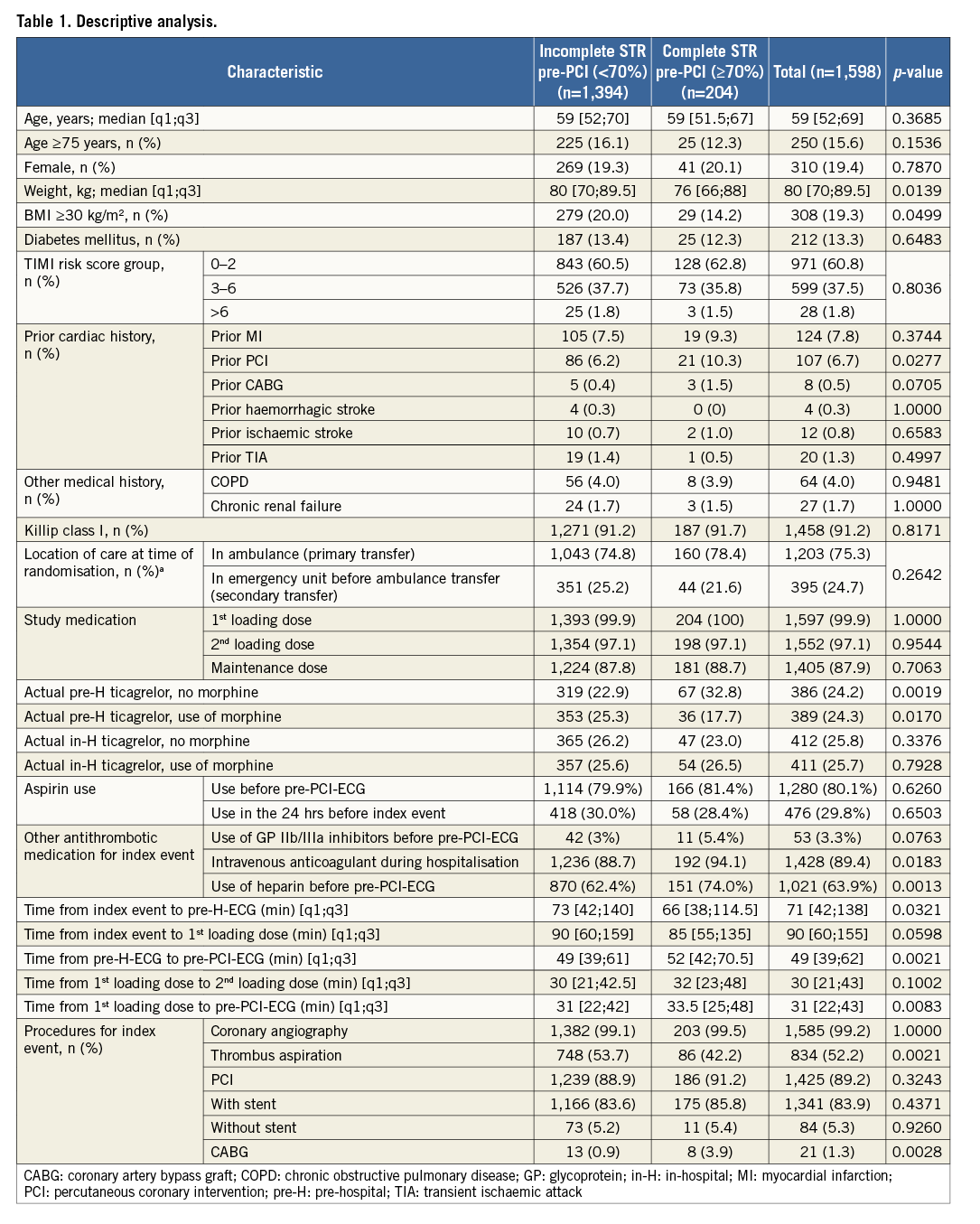

A complete descriptive analysis of patients with pre-PCI complete STR compared to incomplete STR is shown in Table 1.

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

A total of 1,598 patients with both pre-H and pre-PCI-ECGs available were included in the present analysis. Complete STR pre-PCI occurred in 12.8% (n=204/1,598) of patients. Patients with complete STR were less frequently obese (weight: median [q1;q3], 76 [66;88] vs. 80 [70;89.5] kg, p=0.014; body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m², 14.2% vs. 20%, p=0.0499) compared with incomplete STR. Patients with a prior PCI more often had complete STR (10.3% vs 6.2%, p=0.028). No other patient demographic characteristics were significantly different between the two groups.

PRE-HOSPITAL PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT

Use of aspirin before pre-PCI-ECG (80.1%) or its use in the 24 hours before the index event (29.8%) as well as the use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors before pre-PCI-ECG (3.3%) was not different between the complete STR and incomplete STR groups. Conversely, the use of heparin (any type) before pre-PCI-ECG was more frequent in the complete STR group (74% vs. 62.4%, p=0.001).

Moreover, the complete STR group more frequently received pre-H ticagrelor administration without concomitant morphine use, compared with the incomplete STR group (32.8% vs. 22.9%, p=0.002). Conversely, the concomitant use of morphine and pre-H ticagrelor was more frequent in the incomplete STR group compared with the complete STR group (25.3% vs. 17.7%, p=0.017). The use of in-H ticagrelor with or without concomitant use of morphine was similar in the complete vs. incomplete STR group.

PRE-HOSPITAL INTERVAL TIMES

Interestingly, the complete STR group exhibited a shorter time interval from the index event to pre-H-ECG (median [q1;q3], 66 [38;114.5] vs. 73 [42;140] mins, p=0.032); conversely, a longer time interval from pre-H-ECG to pre-PCI-ECG (median [q1;q3], 52 [42;70.5] vs. 49 [39;61] mins, p=0.002) and a longer time interval from the first loading dose to the pre-PCI-ECG (median [q1;q3], 33.5 [25;48] vs. 31 [22;42] mins, p=0.008).

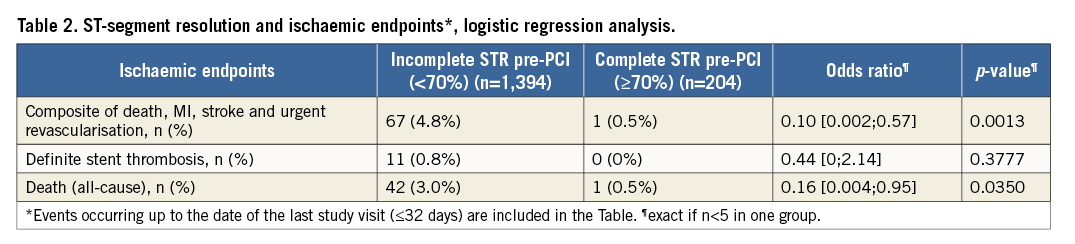

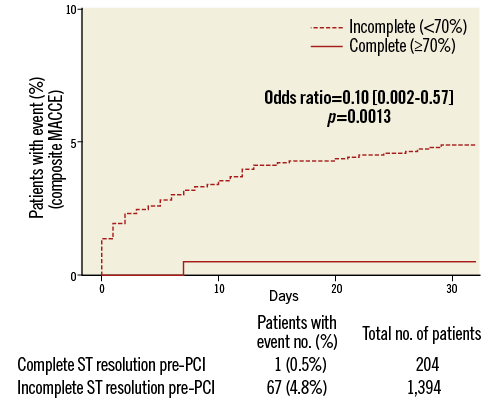

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF PRE-PCI COMPLETE ST RESOLUTION

On logistic regression analysis, complete STR predicted both lower composite MACCE (OR=0.10, 95% CI: 0.002-0.57, p=0.001) and total mortality (OR=0.16, 95% CI: 0.004-0.95, p=0.035) but not definite stent thrombosis (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. There was no association between complete STR and increased bleeding risk, with the exception of minor non-CABG-related bleeding events (PLATO definition) within 48 hours of first dose (Table 3).

Figure 1. Composite MACCE Kaplan-Meier curves in relation to complete and incomplete STR.

Figure 2. Total mortality Kaplan-Meier curves in relation to complete and incomplete STR.

PREDICTORS OF PRE-PCI COMPLETE ST RESOLUTION

Univariate and multivariate analysis of pre-PCI complete STR is presented in Table 4. At multivariate adjusted analysis (with age, sex, BMI, diabetes, prior PCI and prior myocardial infarction as variables forced into the model), modifiable independent predictors for complete STR were the time interval (mins) from index event (onset of symptoms) to pre-H-ECG (OR=0.94, 95% CI: 0.89-1.00, p=0.035), which may represent “patient delay” time, the time from pre-H-ECG to pre-PCI-ECG (OR=1.09, 95% CI: 1.03-1.16, p=0.005), which may represent the transfer delay from ambulance to cathlab, and lastly the use of heparin before pre-PCI-ECG (OR=1.75, 95% CI: 1.25-2.45, p=0.001). Further independent predictors, but non-modifiable in relation to the early management of patients, were BMI <30 kg/m2 (OR=1.56, 95% CI: 1.02-2.39, p=0.039) and prior PCI status (OR=2.15, 95% CI: 1.07-4.35, p=0.033).

EFFECT OF PRE-HOSPITAL TICAGRELOR ON ST RESOLUTION PRE-PCI

There was no significant difference between the pre-H group and the in-H group in terms of the proportion of patients who had complete STR before PCI (13.2% vs. 12.4%, OR=1.07, 95% CI: 0.8-1.44, p=0.63, respectively). In the pre-H ticagrelor group, patients with complete STR had a significantly longer delay between pre-H-ECG and pre-PCI-ECG compared to patients without complete STR (median 53 [44-73] vs. 49 [38.5-61] mins, p=0.00); this was not observed in the control group (in-hospital ticagrelor) (50 [40-67] vs. 49 [39-61] mins, p=0.258) (Table 5).

Discussion

The ATLANTIC ST-segment resolution substudy represents, in the primary PCI era, the largest prospective cohort of STEMI patients focusing on early myocardial reperfusion expressed as complete STR during patient transportation for primary PCI.

Because achieving early myocardial reperfusion is the main goal in STEMI patients, this study evaluated the possible factors influencing early coronary reperfusion before primary PCI. The fact that a longer delay during patient transportation (the time from pre-H-ECG to pre-PCI-ECG) emerged as an independent predictor of complete STR suggests that pre-H antithrombotic treatment may become effective when there is a longer transfer time, allowing the drug to become biologically active. Moreover, it was only in the pre-H ticagrelor group that patients with complete STR had a significantly longer transportation delay compared to patients without complete STR; conversely, this was not observed in the control group (in-H ticagrelor), thus suggesting a possible effect of pre-H ticagrelor administration in patients with longer transfer delay. The possible efficacy of pre-treatment with antiplatelet agents should be viewed in the perspective of an early or delayed access to coronary angiography and revascularisation3. Short medical contact-to-balloon times may explain the absence of a detectable benefit of in-ambulance ticagrelor before the PCI procedure1. However, whereas the short time to PCI achieved in the ATLANTIC study1 represents excellent practice, it may not reflect routine practice. Despite remarkable improvement4, the timeliness of reperfusion therapy for STEMI patients transferred for primary PCI is often prolonged, with a significant proportion of transferred patients not achieving a guideline-recommended5,6 door-to-balloon time of less than 90 minutes4,7. It is evident, therefore, that, in the real world, early administration of potent antiplatelet therapy may represent an opportunity for improving pre-PCI myocardial reperfusion8. This analysis provides further support for a pre-H ticagrelor strategy in STEMI patients, especially for those who still present with a long transfer time. Although this finding can only be considered as hypothesis-generating, the potential benefit of pre-H ticagrelor administration should not be denied, especially considering its proven safety1. This is in line with the last ESC Guidelines which recommend giving P2Y12 inhibitors at “the time of first medical contact”9, a recommendation which is more specific as compared to the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guidelines which state that P2Y12 inhibitors “should be given as early as possible or at time of primary PCI”6.

A new opportunity to accelerate the onset of action of the antiplatelet effect could be the use of crushed or chewed rather than whole tablets10,11; conversely, the use of morphine was shown to delay the absorption and onset of action of ticagrelor1,12. Moreover, the possible delay in ticagrelor absorption in the setting of STEMI cannot be overcome by increasing loading dose regimens13. Pre-H administration of a fast-acting antiplatelet agent, such as cangrelor14, may represent a new strategy to be tested in order to improve pre-PCI reperfusion.

The importance of in-ambulance treatment is also suggested by the fact that early use of heparin (before pre-PCI-ECG) was an independent predictor of complete pre-PCI STR. This suggests that the earlier heparin is instituted, the greater the therapeutic benefit. This is in line with current guidelines that strongly recommend, despite the paucity of evidence15,16, early administration of an anticoagulant at the time of diagnosis, and also with the common practice among many European emergency medical services to give an anticoagulant as soon as possible, including in the pre-H setting.

Interestingly, complete STR was more frequent in patients with lower weight and BMI, and BMI <30 kg/m2 emerged as an independent predictor of complete STR. This may reflect the possible influence of BMI on the efficacy of antithrombotic therapy17; however, ticagrelor efficacy is not influenced by BMI18.

Another independent predictor of complete STR was short “patient delay” (the time from index event to pre-H-ECG). This emphasises, once more19,20, that the delay between symptom onset and diagnosis (first ECG) should be minimised as much as possible. The early period after symptom onset represents a golden opportunity for antithrombotic therapy, because the platelet content of the fresh coronary thrombus is maximal and more susceptible to powerful antiplatelet agents21. Moreover, early reperfusion after symptom onset has the maximal life-saving potential, through myocardial salvage. Patient education is an important component in reducing this delay22, and it is interesting that, in this analysis, prior PCI status was another independent predictor of complete STR. One might speculate that these patients recognised the symptoms of acute myocardial infarction and took timely action to seek medical help.

The ATLANTIC ST-segment resolution analysis highlights the elements that may help to achieve reperfusion before primary PCI. This is particularly relevant considering that this substudy confirmed19,23,24 the prognostic importance of electrocardiographic assessments of early reperfusion, showing that pre-PCI complete STR represents a valid surrogate marker for cardiovascular clinical outcomes, namely MACCE and death (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Finally, the reduction in ischaemic complications associated with pre-PCI complete STR was not associated with an excess of major bleeding. This result was consistent across all the definitions and types of bleeding adjudicated by the clinical endpoint committee, with the exception of a signal for more early minor bleeding.

Limitations

First, this analysis was a post hoc analysis and therefore should be viewed as hypothesis-generating. Second, continuous ST-segment monitoring was not used, thereby precluding the identification of dynamic changes that may be observed during the acute phase of STEMI. Third, this analysis considered only STR as a marker of myocardial reperfusion and did not consider TIMI 3 flow in the culprit artery. However, patients with STR are likely to have a patent infarct artery25. Moreover, STR can be considered a surrogate for tissue-level reperfusion23 and, in the fibrinolytic era, STR showed a prognostic power that persists even after accounting for the effects of epicardial blood flow26. Overall, there was a small difference between the different time intervals that have been considered; however, this study identified clear independent predictors of outcome with clinical applicability. Finally, the possibility of unaccounted confounding related to the non-randomised administration of heparin cannot be excluded; therefore, the potential benefit of early heparin administration requires confirmation in future studies.

Conclusions

Pre-PCI complete STR is a valid surrogate marker for cardiovascular clinical outcomes. Short patient delay, early administration of an anticoagulant and ticagrelor if a long transfer delay is expected may help to achieve reperfusion prior to PCI. The fact that a longer delay during patient transportation emerged as an independent predictor of complete STR suggests that pre-H treatment may be beneficial in patients with longer transfer delays, allowing the drug to become biologically active.

| Impact on daily practice In patients with STEMI being transported for primary percutaneous coronary intervention, pre-hospital treatment with an anticoagulant and ticagrelor in addition to aspirin if a long transfer delay is expected may help to achieve reperfusion prior to PCI. This provides support for a pre-hospital strategy treatment for those who still present with a long transfer time. |

Funding

This study was supported by AstraZeneca.

Conflict of interest statement

L. Bolognese reports receiving personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Menarini Ind Farma, Abbott, AstraZeneca, and Iroko Cardio International, outside the submitted work. W. Cantor reports receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. A. Cequier reports receiving research grants from AstraZeneca, Abbott, Medtronic, Spanish Society of Cardiology; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Ferrer International; and lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly and Servier. M. Chettibi reports receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, during the conduct of the study. S. Goodman reports other support from AstraZeneca Canada, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. C. Hamm reports receiving grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Lilly, Sanofi-Aventis, and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. C. Hammett reports receiving grants from AstraZeneca, during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen, and The Medicines Company, outside the submitted work. M. Janzon reports receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca during the conduct of the study. F. Lapostolle reports receiving grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca; grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, Lilly, Correvio, Daiichi-Sankyo, The Medicines Company, during the conduct of the study; and grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Merck-Serono, Roche, outside the submitted work. J. Lassen reports receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. G. Montalescot reports receiving grants from ADIR, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celladon, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, ICAN, Fédération Française de Cardiologie, Medtronic, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and The Medicines Company, and personal fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Berlin Chimie AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical, Brigham Women’s Hospital, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, CME Resources, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Europa, Elsevier, Fondazione Anna Maria Sechi per il Cuore, Gilead, Janssen, Lead-Up, Menarini, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, The Medicines Company, TIMI Study Group, WebMD, outside the submitted work. R. Storey reports receiving grants from AstraZeneca, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Correvio, The Medicines Company, Medscape, grants and personal fees from PlaqueTec, personal fees from Aspen, ThermoFisher Scientific, other from Medtronic, outside the submitted work. J. ten Berg reports receiving grants from ASTRA, personal fees from MSD, Daiichi-Sankyo Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. A. van ‘t Hof reports receiving grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, during the conduct of the study; grants from Medtronic, Daiichi-Sankyo, personal fees from Iroko Cardio, outside the submitted work. E. Vicaut reports receiving grants from Boehringer, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Pfizer, Sanofi, LFB, Abbott, Fresenius, Medtronic, Hexacath, CERC, Novartis, Eli Lilly, grants from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. U. Zeymer reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, personal fees from Bayer Healthcare, The Medicines Company, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, Novartis, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.