“At some point, everything's gonna go south on you and you're going to say, this is it. This is how I end. Now you can either accept that, or you can get to work. That's all it is. You just begin. You do the math. You solve one problem and you solve the next one, and then the next. And if you solve enough problems, you get to come home.” – Mark Watney from the movie “The Martian”.

Stoicism is an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy that has become popular in the 21st century as a guide to how to live our lives. The key goal of Stoic philosophy is to live by virtue and achieve tranquillity, i.e., absence of negative emotions (such as fear, anger, grief) and presence of positive emotions (such as joy). In addition to improving the overall quality of our life, achieving tranquillity can have a profound effect on the outcomes of complex procedures, such as chronic total occlusion (CTO) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

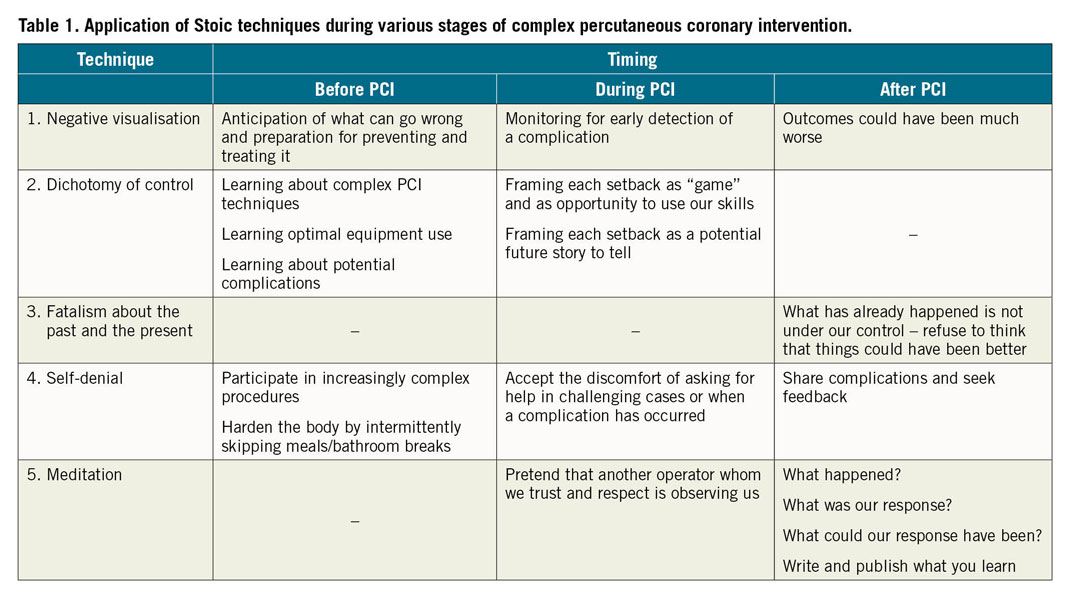

William B. Irvine in his book “A guide to the good life” lists five key Stoic techniques1:

1. Negative visualisation: consideration of how things could be much worse than they are, which can make us happier for having what we have.

2. Dichotomy of control: we should occupy ourselves only with what is under our control, as it makes no sense to occupy ourselves with things we do not control.

3. Fatalism about the past and the present. This is an application of the dichotomy of control: we cannot change the past and the present, hence there is no point in thinking or wishing that they were different. Whatever happened or is happening now will not change, no matter how much we wish it did.

4. Self-denial, i.e., voluntary discomfort, which prepares us to face future setbacks and adversities.

5. Meditation. Recount the events of the day to determine whether we are responding to the events of life according to Stoic principles.

Here is how the aforementioned techniques can help to optimise the outcomes of complex PCI, before, during and after the procedure (Table 1).

1. NEGATIVE VISUALISATION

Negative visualisation can help the operator to prepare for the procedure: thinking about what could go wrong before the procedure helps the operator prepare for it, by learning how to prevent each complication and how to treat it should it arise. For example, having covered stents and coils in the catheterisation laboratory is important for treating a coronary perforation promptly and effectively. Negative visualisation is also important during the procedure: by thinking about what could potentially go wrong, the operator can detect a complication early and take corrective action. Monitoring during PCI2 is a form of negative visualisation: it involves imagining what could go wrong and checking on whether it actually has. Finally, negative visualisation is useful after the procedure is completed, in case of failure or a complication. Things could always be worse: if the procedure fails but the patient experiences no complication, we can be grateful for the latter. If the patient has a treatable complication, we can be grateful it can be treated. If the patient dies, we can be grateful that we are alive. Almost regardless of how bad things are, they could always have been worse, and this alone is reason to give thanks3.

2. DICHOTOMY OF CONTROL

Understanding what is under our control has profound implications regarding how we prepare and perform complex PCI. The outcome of complex PCI is only partially under our control: what we control is our preparation and execution, and how we respond to potential setbacks during the procedure. We do not control the patient’s coronary anatomy and comorbidities, or the performance of the other members of the team. It is, therefore, possible for us to do our best, but still have a suboptimal clinical outcome. At the same time, focusing on what we control increases the likelihood of a good procedural outcome. What we control includes the following:

a. Overall knowledge and experience: doing, watching and reading about as many clinical scenarios as possible improves our treatment algorithms and manual dexterity.

b. Understanding how to use the available equipment optimally, especially those things which are infrequently used, such as covered stents, coils and snares.

c. Learning what can go wrong and how to prevent and treat it.

d. How we frame setbacks: we just crossed a CTO, but had difficulty delivering a balloon and lost guidewire position. A common response to this scenario is anger and frustration, which in turn reduces the chance of successfully recrossing the CTO. Keeping calm and collected increases the likelihood of succeeding in recrossing the CTO and achieving a good final outcome.

How we frame every difficulty, complication or setback is under our control and can tremendously affect how we respond and how we feel. For example, we just crossed a CTO with a guidewire after several hours of attempts, but no balloon can cross the lesion. We can view this as an unfair and cruel additional difficulty, as a “conspiracy of nature”. This framing of the balloon uncrossable challenge will probably result in negative emotions (“victim” mentality – “life is not fair”). Alternatively, we can frame it as a “game”: we are given an opportunity to show our resourcefulness and skills! Using the “game frame” will probably lead to better emotions and a better response compared with the “victim” frame. Perceiving potential threats as opportunities for personal growth and thriving in changing environments is a key component of mental toughness4.

The “storytelling” frame can also be useful, for example thinking what a great story this case will make in the future if it eventually goes well. This can help shift the operator’s focus from frustration and anger to searching for a solution to the problem, which could subsequently be shared with others, potentially helping them. The fluoro-store function, available in all contemporary X-ray systems, is very useful for capturing on film an unexpected event after it has occurred, hence building the blocks for our future story.

3. FATALISM ABOUT THE PAST AND THE PRESENT

Fatalism about the past and the present can be useful in case of poor outcomes or tough time points during the procedure. Blaming ourselves or others will not change anything and will make things worse. By refusing to think how things could have been better we can focus instead on how things currently are and find solutions to our problems.

4. SELF-DENIAL

Complex PCI will often lead to uncomfortable moments, when unexpected challenges (such as inability to engage the coronary artery, inability to advance a guidewire, and inability to deliver equipment to the target lesion) or complications arise. “You have to be comfortable being uncomfortable” is a frequent piece of advice to complex PCI operators. However, “comfort” arises from experience: the first time we witness a perforation or lose a stent we will probably be more stressed than after we experience several of those complications. This does not imply that we should go out of our way to inflict complications so that we can become adept in treating them! Instead, we can seek voluntary discomfort by participating in increasingly complex procedures, ideally with the help of a proctor or a more experienced operator. Occasionally skipping meals and bathroom breaks can help us to become more confident that we can handle physical distress during prolonged complex procedures. Accepting the discomfort associated with sharing our misadventures with others can help us learn what we could do better in the future.

5. MEDITATION

Meditation in the setting of complex PCI means reviewing each challenging or complicated case focusing on the following:

i. What happened?

ii. What was our response to what happened?

iii. What could our response have been?

The goal of this review is to learn and improve. Meditation is a form of “being observed”. We behave better when we know that someone is observing us, for example during visits of the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Knowing that we will review our actions after each difficult case can help to improve our response during the course of each case. We can also pretend that another operator whom we trust and respect is constantly observing us: what would Dr XYZ do under these circumstances? How would he or she respond?

Writing and publishing challenging or complicated cases in print or in social media is another form of meditation. It can help to clear our thoughts about what happened, help others learn and often leads to constructive feedback. A few years ago one of my patients who had prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery died during CTO PCI due to distal vessel perforation5. That experience helped me to prevent similar complications subsequently, and publishing it was also very helpful when the case was peer reviewed. Presentations of complications and poor outcomes (for example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ta_qwiFS2-Y&t=4s) are often the most anticipated content during both in-person and online meetings.

Achieving tranquillity makes us function better, but what is the ultimate goal of all we do, including when performing complex PCI? Helping others. According to Musonius Rufus, one of the Roman Stoic philosophers, “I am bound to do good to my fellow creatures and bear with them”. The goal of every medical act, including PCI and complex PCI, is to help the patient. The primary goal is not to impress others or personal gain. The Stoics’ advice to be content with what we have and to limit our desires prepares us well to do what is best for each patient who entrusts us with his or her care.

Conflict of interest statement

E. Brilakis reports consulting/speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular, American Heart Association (associate editor Circulation), Amgen, Asahi Intecc, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Innovations Foundation (Board of Directors), ControlRad, CSI, Elsevier, GE Healthcare, Infraredx, Medicure, Medtronic, Opsens, Siemens, and Teleflex, being the owner of Hippocrates LLC, and being a shareholder in MHI Ventures, Cleerly Health.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.