CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 72-year-old patient presented with severe dyspnoea and peripheral oedema.

INVESTIGATION: Physical examination, electrocardiography, laboratory tests, echocardiogram, coronary angiography, aortography of the ascending aorta.

DIAGNOSIS: Severe aortic valve stenosis.

MANAGEMENT: Transaortic valve implantation (CoreValve).

KEYWORDS: aortic valve stenosis, CoreValve, paravalvular leakage, snare, TAVI

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

A 72-year-old patient (height: 168 cm; weight: 70 kg) was admitted to our hospital for a New York Heart Association functional Class IV of dyspnoea and oedema of the lower legs.

The transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a heavily calcified aortic valve and a severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. A transaortic pressure gradient of 56/33 mmHg (dPmax/dPmean) with a calculated aortic valve orifice area of 0.7 cm2 (continuity equation) was detected. As a consequence of the patient’s comorbidities (EuroSCORE 31, chronic lymphatic leukaemia), the decision in favour of transcatheter valve implantation (TAVI) (CoreValve Revalving System; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was taken. In order to rule out relevant coronary artery stenosis, to determine the optimal vascular approach and to define aortic root diameters, preoperative diagnostics were supplemented by angiography and transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) was spared because of renal failure and good quality of the TEE images. Based on the TEE and angiographic measurements (Table 1) a 26 mm inflow CoreValve® device was chosen.

The CoreValve procedure was performed as recommended1. First, valvuloplasty of the native aortic valve was performed with a 22 mm balloon (percutaneous aortic balloon valvuloplasty; NuMED Inc., Hopkinton, NY, USA) using rapid ventricular pacing (200 bp/min). Next, the 26 mm CoreValve prosthesis (Medtronic) was placed to a depth of 13 mm below the base of the aortic annulus.

Post-implantation haemodynamics revealed a complete release of the transvalvular pressure gradient. The left ventricular pressure tracing showed an end-diastolic pressure of 28 mmHg compared to 20 mmHg before TAVI. Aortic diastolic pressure decreased from 60 mmHg before to 40 mmHg after the procedure. As diagnosed by aortography and transoesophageal echocardiography, severe paravalvular aortic valve regurgitation was present (Moving image 1, Moving image 2). For a better apposition of the prosthetic valve a second balloon dilation with a 25 mm balloon (percutaneous aortic balloon valvuloplasty; NuMed) was performed, but no improvement of the regurgitation was achieved.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

Case selection, procedure and the severity of paravalvular aortic regurgitation

The case presented is of severe paravalvular aortic regurgitation (AR) related to low malpositioning of a 26 mm Medtronic CoreValve (MCV) bioprosthesis performed by a transaortic approach. The prosthesis was sized by two-dimensional transoesophageal (2-D TOE). The 23 mm annulus size by 2-D TOE is at the upper limit of that acceptable for a 26 mm MCV. Contrast CT would have been preferred but could not be performed due to renal failure. The valve is described as severely calcified on transthoracic echocardiography, itself a substrate for paravalvular regurgitation. A non-contrast cardiac CT would have been of value for quantification of both aortic valve and left ventricular outflow tract (or “landing zone”) calcification2. The end-diastolic pressure increased from 20 to 28 mmHg and the aortic diastolic pressure decreased from 60 to 40 mmHg. Therefore, the end-diastolic transaortic pressure gradient decreased from 40 to only 12 mmHg, indicative of significant aortic regurgitation. The aortic systolic pressure is not provided and so the AR index3 cannot be calculated.

The mechanism of paravalvular aortic regurgitation

The authors describe low malpositioning of the prosthesis 13 mm below the native annulus. Importantly, the covered skirt at the ventricular end of the MCV prosthesis measures 12 mm. Because of this, the leak occurs through the uncovered struts of the stent frame directly into the left ventricle. Due to this, it was extremely unlikely that post-dilatation would have improved the regurgitation as the mechanism is not that of stent frame malapposition.

Treatment options

While making a final decision and preparing for definitive manoeuvres, increasing the heart rate with the temporary pacemaker at 80-100 beats per minute can help by increasing the gradient between the LVEDP and aortic diastolic pressure, thereby stabilising the patient.

1. Medical therapy with vasodilators.

This is an established therapy for significant native chronic AR4 but is a less preferred option in this acute setting.

2. Surgery.

Although surgery is an option, this patient carries a considerable operative risk and with a (logistic) EuroSCORE of 31 it may be considered futile.

3. Transcatheter valve-in-valve (V-in-V).

This is an established effective manoeuvre in this setting5. A relatively minor downside of V-in-V is an excess of pacemaker.

4. Snare and pull.

The MCV has two hooks at the aortic end of the stent frame that may be snared and the transaortic sheath would provide a good orientation for traction. This snare and pull technique6 is the most preferred initial therapy in this setting, although care must be taken to avoid embolisation, otherwise known as “dislocation”, to the aorta.

Conflict of interest statement

H. Jilaihawi is a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, St. Jude Medical and Venus Medtech. R.R. Makkar receives a research grant from Edwards Lifesciences, is a consultant for Abbott Vascular, Cordis, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical, and is a stockholder in Entourage Medical. T. Chakravarty has no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

Paravalvular aortic regurgitation (PVAR) is common following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Most PVAR is mild whilst some may improve with time, e.g., as the nitinol frame of the CoreValve prosthesis expands further7. Periprocedural assessment of the severity of PVAR is challenging and all available information should be taken into consideration. Colour Doppler echocardiography and contrast aortic root angiography can be misleading especially in the presence of severe AR with early diastolic pressure equalisation between the aorta and left ventricle (LV)8,9. The aortic pressure and LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) should be assessed prior to and after prosthesis implantation9. A low or decreased gradient between aortic diastolic pressure and LVEDP or a high or increased LVEDP indicates significant PVAR. The common reasons for PVAR are related to “deep” implantation, undersizing or underexpansion of the prosthesis, and each warrants a different management strategy10.

In this case, the imaging and haemodynamic data indicate severe PVAR following implantation of a 26 mm CoreValve prosthesis. The relative size of the aortic root and implanted prosthesis suggests that prosthesis undersizing is the likely cause of PVAR. The 23 mm annular diameter measured on transoesophageal echocardiography is at the cut-off point for selecting a 26 mm or 29 mm prosthesis. The aortic annulus is oval in shape and the measurement from a long-axis view of the echocardiogram is that of a tangent across the annulus rather than its true diameters11. Annular measurements by two- or three-dimensional echocardiography and contrast fluoroscopy are smaller than those by multidetector computed tomography12-14, which is the recommended imaging modality, and annular diameter can be derived from its area. Increasingly, three-dimensional transoesophageal echocardiography is being used, as it allows real-time assessment of aortic root geometry14. The only option to implant a second and larger prosthesis is to snare the eyelet situated closer to the inner curve of the aortic arch and pull the existing prosthesis into the ascending aorta before implanting the larger prosthesis.

PVAR in this case may be partly attributed to deep implantation of the prosthesis, 13 mm into the LV outflow tract. PVAR associated with the CoreValve can occur through the uncovered frame struts above the pericardial skirt, which is at least 12 mm in height. Generally, “valve-in-valve” implantation of a second prosthesis at a higher position is the preferred option10,15, and the aortic end of the prosthesis serves as an ideal landmark to guide the deployment of the second prosthesis. Attempting to “snare-and-pull” the prosthesis to a higher position may be efficient but has to be weighed against the risk of vascular complications. This strategy should be reserved for cases such as prosthesis undersizing or impingement to mitral valve function.

Post-dilatation is effective for PVAR due to prosthesis underexpansion caused by, e.g., unfavourable valvular calcification. Therefore, it was ineffective in this case. Post-dilatation should be performed under fast-rate pacing and the balloon size should not exceed the annular dimensions in order to avoid annular rupture.

Taking everything into consideration, we would initially “snare-and-pull” the prosthesis to a higher position within the annulus. If the improvement in PVAR was unsatisfactory, we would “snare-and-pull” the prosthesis into the ascending aorta to a position high enough for implantation of a 29 mm prosthesis. Careful assessment of the severity and mechanism(s) of PVAR is the key to a systematic approach to its management. This is vital as worse PVAR predicts poorer patient outcome16.

Conflict of interest statement

O. Franzen is a TAVI proctor for Edwards Lifesciences. L. Søndergaard is a TAVI proctor for Medtronic. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE CASE

Aortic valve regurgitation is a frequently observed aspect after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)17-20. Balloon dilation is often useful in case of malapposition or underexpansion of the device, but it failed to improve the result in this case, probably due to the deep implantation and the small size of the valve.

Although the patient was stable, rapid deterioration of the haemodynamic situation had to be expected as a consequence of the preceding left ventricular failure and the acute increase in ventricular volume load. As a consequence of the patient’s comorbidities an open cardiac surgery was not an option. An interventional attempt to occlude the paravalvular leakage by using AMPLATZER® vascular plugs (St. Jude Medical Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) failed. The last choice was to implant a 29 mm CoreValve prosthesis after removal of the 26 mm device. As illustrated in a previous case report by Hoffmann et al21, repositioning of a CoreValve prosthesis by using a snare resulted in a nearly complete release of severe paravalvular regurgitation.

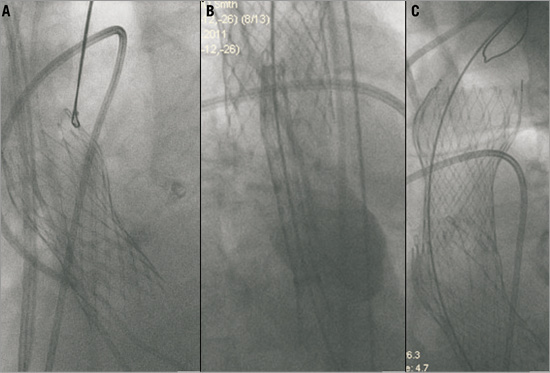

The CoreValve® device has two hooks at the distal end of the stent frame in order to allow attachment to the delivery catheter. One of these hooks of the already positioned and released 26 mm valve was snared with a 25 mm EN snare (Merit Medical Systems Inc., South Jordan, UT, USA) from a left brachial access (Moving image 2 and Moving image 3). Afterwards the device was pulled back into the ascending aorta. Finally a 29 mm CoreValve® was implanted via a femoral access. Control aortography revealed only mild aortic valve regurgitation (Figure 1, Figure 2, Moving image 4 and Moving image 5). The patient was discharged and referred for rehab 3 weeks after the procedure.

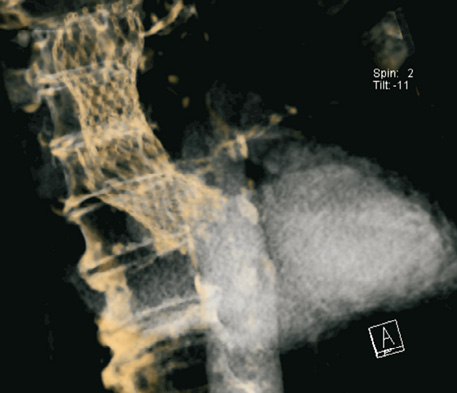

Figure 1. Computer tomographic 3-D reconstruction after retraction of the 26 mm CoreValve® prosthesis and implantation of a 29 mm device.

Figure 2. Retraction of the 26 mm CoreValve® device (A) followed by implantation of a 29 mm prosthesis (B, C).

This case report illustrates that severe paravalvular leakage after CoreValve implantation can be managed by implanting a larger valve after retracting the smaller prosthesis.

Conflict of interest statement

H. Ince serves as a proctor for the CoreValve procedure of Medtronic, Germany. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Online data supplement

Moving image 1. Final angiographic evaluation.

Moving image 2. Severe paravalvular leakage after implantation of a 26 mm CoreValve, depicted by transoesophageal echocardiography.

Moving image 3. Snared 26 mm CoreValve prosthesis.

Moving image 4. Retracted 26 mm CoreValve prosthesis and release of the larger 29 mm valve.

Moving image 5. Fluoroscopic illustration of the two implanted valves.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Moving image 1. Final angiographic evaluation.

Moving image 2. Severe paravalvular leakage after implantation of a 26 mm CoreValve, depicted by transoesophageal echocardiography.

Moving image 3. Snared 26 mm CoreValve prosthesis.

Moving image 4. Retracted 26 mm CoreValve prosthesis and release of the larger 29 mm valve.

Moving image 5. Fluoroscopic illustration of the two implanted valves.