CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 53-year-old male with a prior history of refractory arterial hypertension was admitted to our institution because of headache and high blood pressure, 220/120 mmHg. With the suspicion of an aortic dissection a CTA was performed.

INVESTIGATION: The aortic CTA revealed an aortic coarctation with chronic type B dissection of the descending aorta up to both iliac arteries. Transthoracic echocardiography showed a bicuspid valve with severe regurgitation, but normal LV volume and function.

DIAGNOSIS: Bicuspid valve, aortic coarctation and chronic type B dissection of the descending aorta.

MANAGEMENT: Percutaneous stenting (covered stent) of the coarctation followed by a long stenting of the dissection.

KEYWORDS: coarctation, chronic descending aorta dissection, CP stent

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

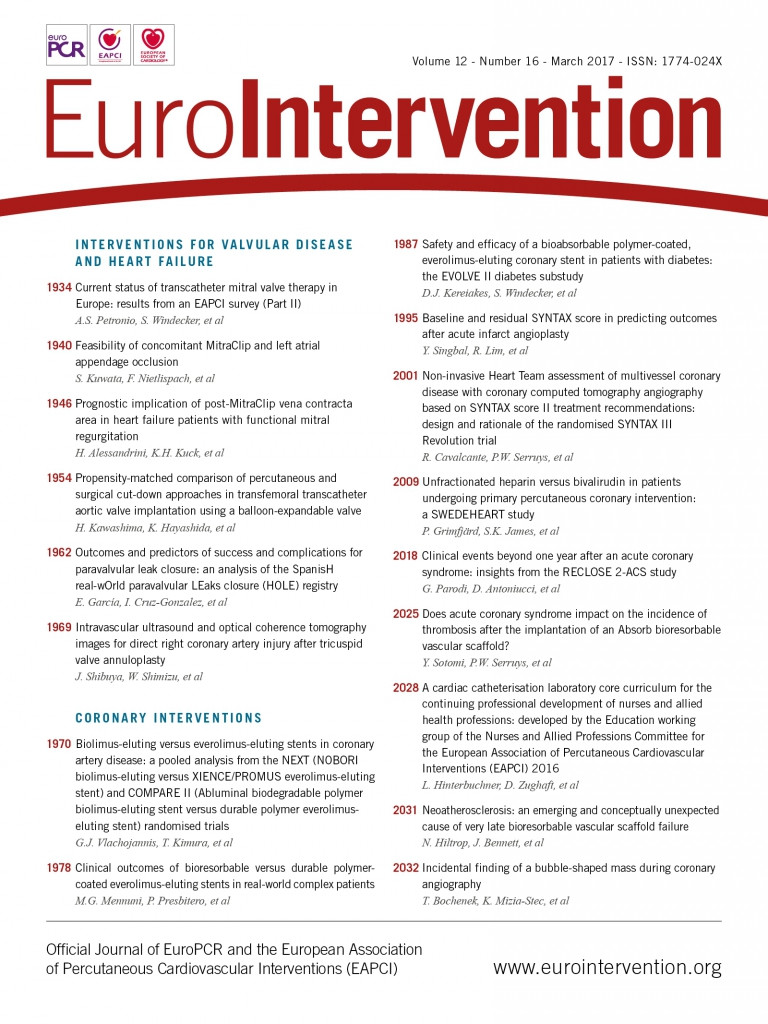

A 53-year-old male with a history of refractory arterial hypertension was admitted to our institution because of headache and high blood pressure. With the suspicion of an aortic dissection, an aortic CTA was performed revealing an aortic coarctation just below the left subclavian artery followed by a severe dilatation of the thoracic aorta (55 mm) due to a large chronic type B dissection (type B) (Figure 1A, Figure 1B). The true lumen diameter was 10 mm and all main arterial branches except the right renal artery kept their flow from this true lumen. The dissection progressed towards the left common iliac artery and got stopped at the external iliac branch.

Figure 1. Aortic CTA and 3D reconstruction of the thoracic aorta. A) The aortic coarctation with the narrowest zone of 11×17 mm, localised below the origin of the left subclavian artery. B) Severe dilatation of the thoracic aorta (55 mm) with a large chronic dissection (type B) and large proximal entrance from the true lumen (10 mm) to the false lumen.

Because of the frequent association of aortic coarctation with the bicuspid valve, transthoracic echocardiography was performed showing severe aortic regurgitation due to a bicuspid valve with normal ventricular volumes and normal ejection fraction (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] 60%). The coronary CTA showed normal coronary arteries and no dilatation of the aortic root (35 mm).

The Heart Team discussed the case and it was considered that the aortic coarctation and dissection should be addressed first and that the aortic valve could be treated at a later time point if needed (since the patient was asymptomatic, and the ventricular volumes and EF were normal). Therefore, the percutaneous approach was favoured.

How should we deal with this complex coarctation with concomitant dissection of the descending aorta?

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERT’S OPINION

Bicuspid aortic valve is the supreme congenital cardiovascular anomaly, striking 2% of the population who have an autosomal dominant inheritance. The most common complications are aortic stenosis, regurgitation and infective endocarditis.

Coarctation of the aorta is considered a localised deformity, commonly distal to the left subclavian artery, but it must be deemed a diffuse arteriopathy and part of the spectrum of pathology associated with the bicuspid aortic valve. Moreover, 10% of patients with coarctation have intracranial aneurysms; this supports the hypothesis of a more diffuse arterial pathophysiology, due to a developmental abnormality of neural crest tissue that gives rise to the muscular arteries of the heart, aortic arch, and cervico-cephalic arteries.

The occurrence of a bicuspid valve increases the risk of dissection ninefold. The dissection hits younger patients, predominantly due to cystic medial necrosis and aortopathy. The apoptosis leads to the loss of smooth muscle cells in the aorta of patients with a bicuspid aortic valve. A genetic signal advances the apoptosis with the stimulus of hypertension. That is why there is a higher incidence of dissection and rupture with coexistent coarctation of the aorta. The scanty production of fibrillin-1 during valvulogenesis alters the formation of both the aortic cusps and root and reduces their structural integrity. This pathophysiology is crucial in the strategic mapping of the management of such complex cases with the choice of endovascular vs. open surgical repair.

The ESC guidelines for valvular heart disease in patients with a bicuspid aortic valve are based on patient age, body size, comorbidities, type of surgery, and the presence of family history, systemic hypertension, dissection and coarctation of the aorta.

When coarctation of the aorta is associated with one or more congenital or acquired cardiac defects, surgery is the first option and the gold standard, though there are no standard management guidelines for these complex and challenging pathological conditions.

Controversy exists not only as to which lesion should be corrected first, but also concerning the type and timing of the procedure. Surgery can be performed as a one- or two-stage hybrid procedure. The one-stage approach can be accomplished through a single or two incisions, and the two-stage approach involves two operations performed through a median sternotomy and a posteriolateral thoracotomy, respectively, with a gap of weeks to months. Both of these strategies have their merits and demerits. The option of choosing one of these procedures depends upon pathology and the experience of the managing team concerned.

For this particular case, we would recommend aortic valve surgery performed with concomitant correction of the aortic coarctation and dissection, with surgical de-branching of the left subclavian artery to the left common carotid artery. This should be followed by thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair (TEVAR) through a gradual dilation of the tight infantile adult aortic coarctation over one hour, with a covered stent graft of the first 15 cm distal to the left common carotid artery, and followed by endovascular fenestration and stenting to the right renal artery that is supplied from the false dissected lumen.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

The optimal management of patients with dissection of the descending aorta remains a major challenge and demands a multidisciplinary approach to assess each patient and decide whether endovascular or open surgical treatment, or further medical management is indicated. This case is further complicated by the presence of a previously unrecognised native aortic coarctation and severe bicuspid aortic regurgitation.

Firstly, the bicuspid aortic valve regurgitation, although severe when considered in isolation, does not meet current criteria for intervention but rather for surveillance as there are no symptoms referable to this lesion, the left ventricular volumes and function are normal and the ascending aorta is not dilated1.

The presence of refractory hypertension, native aortic coarctation, severe dilation (55 mm) of the proximal descending aorta and evidence of chronic descending aortic dissection with a 10 mm communication between the false and true lumen are factors that mitigate against medical management being a successful long-term strategy2.

The initial management of this patient should be focused on the control of blood pressure to reduce aortic wall stress. The definitive management choices are then surgical, endovascular or a combined surgical and endovascular approach. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair may be optimal for treating descending aortic dissection. However, evidence is limited by the paucity of randomised trials2.

The available imaging for this opinion is insufficiently detailed to conclude a final plan dealing with the extensive descending aortic dissection, aneurysm and coarctation while maintaining adequate perfusion of the multiple important aortic branches.

If suitable proximal and distal landing zones are present, then a covered self-expanding aortic stent graft insertion seems the optimal choice. A surgical carotid to subclavian bypass may be required and would allow extension of a stent graft more proximally to a more favourable landing zone. Spinal cord ischaemia and paraplegia is a risk with intervention, though less with endovascular than with surgical repair. The coarctation may require further balloon dilation after deployment of a stent graft due to insufficient radial force if there is a residual gradient. Ideally the gradient across the coarctation segment should be abolished - dilation within a covered stent graft makes this less risky in this aneurysmal and dissected segment. Care also needs to be taken when considering the optimal access route as the report describes extension of the dissection towards the left common iliac artery. On this basis, a right femoral/iliac approach seems preferable.

Finally, the headache, while possibly solely because of hypertension, may be a consequence of intracranial aneurysms as these occur more commonly in patients with aortic coarctation3.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE CASE

The initial strategy was to use two different stents to cover the coarctation and dissection. The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia and guided by fluoroscopy and transoesophageal echocardiography. The right femoral artery was surgically exposed and a 24 Fr sheath (GORE® DrySeal; Gore, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) was inserted. A right humeral artery was obtained with the aim of creating an arterio-arterial loop. Finally, the left femoral vein was acceded for the transitory pacemaker for rapid pacing during stent implantation. A full dose of heparin (100 IU/kg) was given at this point.

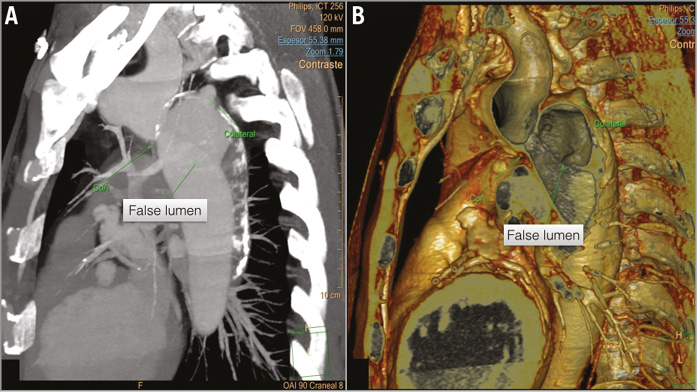

LAO angiography confirmed the presence of the coarctation and the type B dissection. To get a better support for the stent implantation an arterio-arterial loop was created. The coarctation was crossed with a 0.035” Terumo wire (Terumo Corp. Tokyo, Japan) and exteriorised with an Amplatz GooseNeck® Snare (Covidien/Medtronic, Dublin, Republic of Ireland) through the humeral access. Using a straight catheter, the wire was exchanged for a Lunderquist® Extra-Stiff Wire (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) (Moving image 1). First, a 20×45 mm (18 mm BIB) Covered CP Stent™ (NuMED, Inc., Hopkinton, NY, USA) was implanted just below the subclavian artery (Figure 2A). To get better precision and stability, the implant was helped by rapid pacing (180 bpm) and respiratory apnoea. Immediately, a 28-24-150 mm Valiant® thoracic endograft (Medtronic) was deployed (Figure 2B, Figure 2C, Figure 2D). Having the dissection protected, the CP stent was post-dilated with a Reliant® balloon (Medtronic) (Figure 2E). The final angiogram revealed a good apposition of both stents covering the coarctation and sealing completely the entry of the dissection (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. Consecutive implantation of two stents to treat both the coarctation and the dissection. A) & B) A CP Covered Stent is implanted at the coarctation zone. The stent is implanted at nominal pressure with no initial post-dilatation. C) & D) The Valiant stent is placed overlapping the CP stent. E) The CP Covered Stent is post-dilated. F) The final angiogram revealing an adequate opening of the coarctation and adequate sealing of the dissection.

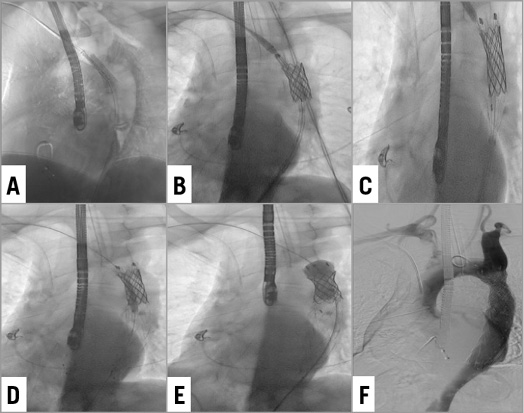

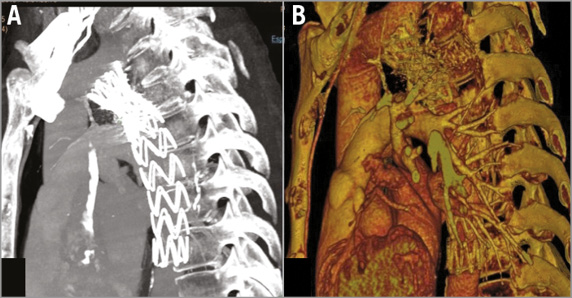

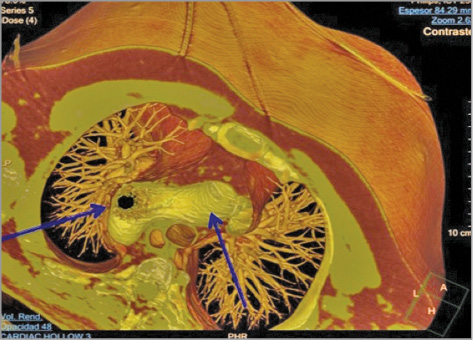

A control CTA was performed at one week showing a good expansion and apposition of both stents (Figure 3A, Figure 3B, Figure 4). The patient was asymptomatic and blood pressure was controlled with medical therapy. No immediate complication related to the procedure was observed.

Figure 3. Aortic CTA – 1-week follow-up. A) Both stents are well apposed and expanded. B) 3D reconstruction.

Figure 4. Aortic CTA – 1-week follow-up. Transversal view.

Discussion

We present an unusual case of a patient with aortic coarctation and concomitant type B dissection. The percutaneous approach has been favoured in adult patients with aortic coarctation and even in patients with type B dissection. However, the simultaneous approach of both pathologies presents some technical difficulties. First, the designs of the stents used for coarctation and dissection are different. The largest CP Covered Stent was too short to cover both the coarctation and dissection, and the stents used for dissection do not have enough radial force to treat a coarctation properly. Therefore, the use of two different stents was completely necessary in this particular case. Second, opening the coarctation might have augmented the flow through the dissection and therefore increased the risk of rupture. For this reason, implanting both stents consecutively with no time delay proved crucial to avoiding major complications. Finally, the patient had a bicuspid valve with severe regurgitation and, despite there being no criteria for surgery at the time, any complication, in particular major bleeding, might have been poorly tolerated. Therefore, the success of the procedure relied on a well-planned strategy and impeccable management of the case.

This case illustrates how a simultaneous aortic coarctation and dissection can be successfully treated percutaneously. The consecutive use of two different stents allowed an adequate expansion of the coarctation and a perfect sealing of the dissection. Since there is no dedicated stent to approach both pathologies, this appears to be an acceptable approach to address this complex case.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

Moving image 1. Stent deployment.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Stent deployment.