CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 70-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department for an acute anterior STEMI six weeks after a previous inferior myocardial infarction.

INVESTIGATION: Coronary angiography, transthoracic echocardiography, cardiac computed tomography.

DIAGNOSIS: Acute anterior myocardial infarction+posterior myocardial wall rupture.

MANAGEMENT: Minimal PCI, thrombectomy, cardiac surgery.

KEYWORDS: acute myocardial infarction, myocardial rupture, thrombectomy, ventricular false aneurysm

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

A 70-year-old man was referred to the emergency department for acute chest pain. His previous medical history included a recent inferior STEMI, which was treated six weeks before in a different institution by implantation of a 3.0×33 mm everolimus-eluting stent on the mid RCA. A significant lesion was diagnosed on the distal LAD during this procedure. The patient’s current treatment included aspirin 75 mg/d, clopidogrel 75 mg/d, atorvastatin 40 mg/d, enalapril 1.25 mg/d and bisoprolol 1.25 mg/d. Other significant medical history included systemic hypertension.

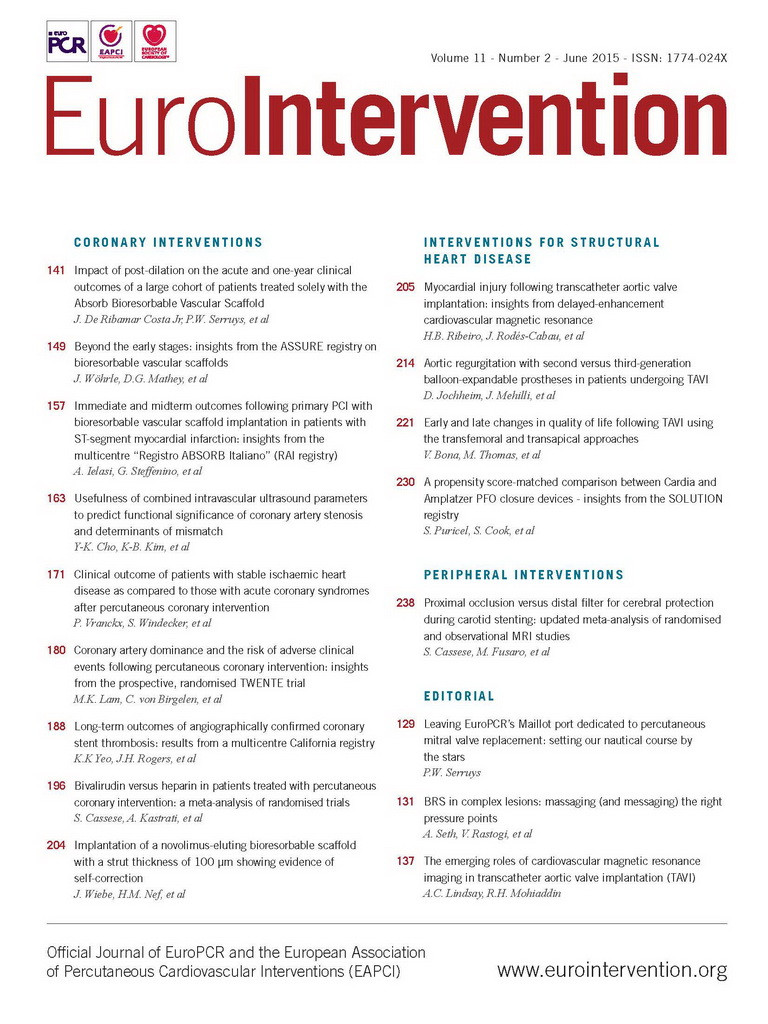

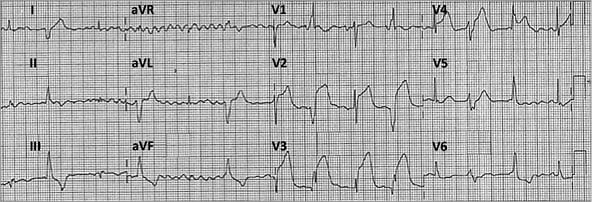

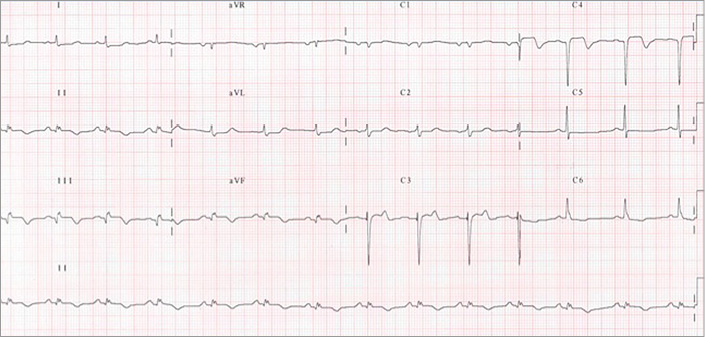

An acute STEMI was diagnosed on the admission electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1). The patient benefited from a transthoracic echocardiography in the ED and was transferred by mobile care unit to the cathlab for urgent coronary angiography. TTE revealed an apical severe hypokinesia (Figure 2A, Moving image 1) and the presence of a posterior left ventricle wall rupture, complicated by a large, partially thrombotic false aneurysm and mild pericardial effusion (Figure 2B, Figure 2C, Moving image 2, Moving image 3).

Figure 1. Admission ECG showed acute anterior myocardial infarction.

Figure 2. Transthoracic echocardiography. Acute apical severe hypokinesia on the four-chamber apical view (A) and presence of an inferior-posterior wall rupture (white arrow) on the two-chamber apical view (B) and parasternal short-axis view (C), complicated by a large ventricular false aneurysm and mural thrombus.

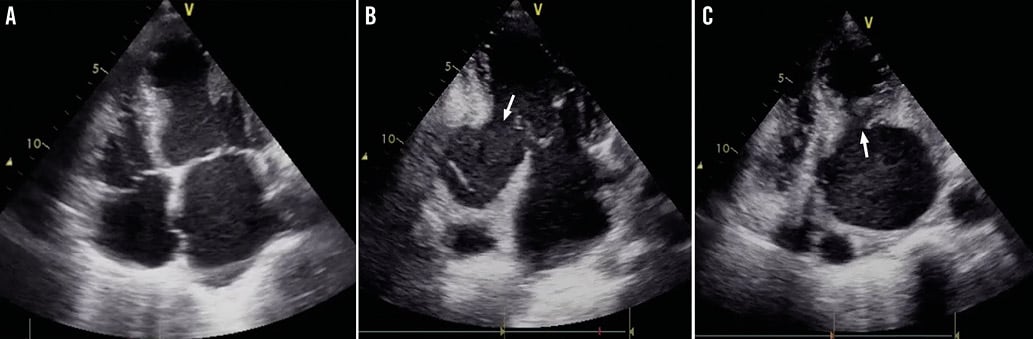

The patient’s haemodynamic condition was stable, with no sign of left ventricle dysfunction (Killip I): heart rate=87 bpm, blood pressure=115/76 mmHg. Coronary angiography (H+300 min after symptoms onset) revealed a permeable stent on the mid RCA (Figure 3A, Moving image 4) and acute thrombotic occlusion of the distal LAD (Figure 3B, Moving image 5).

Figure 3. Coronary angiography. Correct stent permeability on the mid RCA (A) and acute thrombotic distal LAD occlusion (B).

How should I treat this acute myocardial infarction associated with a myocardial rupture in a different coronary territory?

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERT’S OPINION

This 70-year-old gentleman with recent inferior wall STEMI which was treated by primary PCI with implantation of an everolimus-eluting stent in the mid RCA presents again with a STEMI, now of the anterior wall. The ECG shows widespread ST-segment elevations in many precordial leads. The heart rhythm is very irregular due to the presence of atrial fibrillation and ventricular ectopic beats. The interval between the ectopic beats is regular suggesting a ventricular parasystole, most probably originating in the posterolateral region of the left ventricle given the right-axis deviation of the QRS and the monophasic positive R wave in lead V1. The patient is on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) and on statins and ACE inhibitors.

The right coronary artery shows a patent stent in its mid portion.

The left coronary artery shows a fuzzy total occlusion in the distal segment of the LAD. Proximal to this occlusion there is 70% stenosis in the mid LAD just distal from the origin of the first septal branch. The lesion in the mid LAD has smooth contours without any evidence of a recent plaque disruption.

The echocardiogram shows the presence of a huge false aneurysm of the left ventricle in the posterobasal segment with a small neck in the parasternal cross-sectional images and a rather broad neck on the apical two-chamber views. Within the aneurysm there is dense spontaneous contrast and possibly there are thrombi present close to the neck of the aneurysm. Between the mitral valve annulus and the perforation there is only a very small rim of myocardium.

The acute occlusion of the distal LAD could be caused by an acute plaque disruption at the level of the previously described distal LAD stenosis. A coronary embolisation of thrombus originating from the thrombotic false aneurysm, the left atrium or less likely from the lesion in the mid LAD could be another alternative cause of this acute thrombotic occlusion. Given this possibility, I would start with thrombus aspiration after having advanced a soft tip coronary guidewire through the occlusion into the distal LAD.

If after aspiration there remains a significant stenosis in the distal LAD I would stent it. However, if there is no significant stenosis and no angiographic sign of plaque disruption, a coronary embolus is most likely, and in that case I would only stent the mid LAD lesion.

Since the patient is haemodynamically stable with no signs of tamponade, I would keep him on IV bivalirudin and DAPT and order a cardiac computed tomographic angiography examination in order to assess the 3D anatomy of the pseudoaneurysm with special attention to the size of the orifice of the perforation and to the myocardial rim between the mitral valve annulus and the perforation.

If feasible, a percutaneous closure of the perforation under live 3D transoesophageal echocardiography using the previously described method should be considered as an alternative to surgical closure1. Given the need for DAPT after recent multiple stent implantation, a percutaneous closure would provide a clear advantage over cardiac surgery. On the other hand, the presence of ventricular arrhythmias most probably originating from the margins of the infarct favours surgical resection of the pseudoaneurysm.

Funding

The Department of Cardiology at Antwerp University has received research grants from Medtronic, Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERT’S OPINION

This case poses two different problems requiring specific considerations and possibly two different treatments.

One is emergent, namely the treatment of an anterior STEMI in a patient with previous damage to the inferior wall. The other is the management of a subacute mechanical complication with non-haemodynamic relevance at the moment of observation, but with potentially fatal consequences, a situation that should be made clear to the patient and his relatives.

Regarding the first consideration, in favour of primary PCI are the persistence of angina and ST-segment elevation, despite a rather late presentation (>5 hours) with still preserved R waves in the involved leads suggesting tissue viability in the jeopardised territory. Unlike an ordinary STEMI presentation, a great deal of caution is needed in this specific case regarding anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy to reperfuse a relatively small territory (apical) supplied by an occluded distal LAD. Indeed, aggressive antithrombotic drugs may compromise the fragile equilibrium of the spontaneously sealed ruptured myocardial wall.

A primary PCI with the sole aim of limiting the area of necrosis would be my first attempt, with a minimum intravenous dose of unfractionated heparin (3,000 to 5,000 U), manual aspiration and a gentle balloon dilatation to restore flow and avoid stenting, since it would be better to interrupt dual antiplatelet therapy and switch to aspirin alone.

Management of the pseudoaneurysm should be guided by clinical evolution. The echocardiographic images show a small but still present partially organised pericardial effusion, meaning that the rupture is not recent, but may still be alimented by some blood flow. The rupture occurred sometime between the discharge after the inferior infarction and this new presentation. It generally happens one to two weeks after STEMI, and that is at least three weeks before the present anterior STEMI. A magnetic resonance after PCI would provide useful information to help understand the morphology of the pseudoaneurysm better.

Elective surgical repair seems to be the most reasonable approach in a stable patient without haemodynamic impairment. Surgery of the pseudoaneurysm could be performed at any time after PCI of the LAD since the damage of the previous infarction occurred six weeks earlier and has probably healed by fibrotic replacement. Ideally, it would be better to postpone it until the subacute phase of the ongoing anterior infarction2. During this 48 to 72-hour watchful/waiting period an accurate clinical and echocardiographic monitoring is mandatory to anticipate surgery in case of an increment of the pericardial effusion or the occurrence of signs or symptoms indicative of late re-bleeding and further expansion in the pericardial space (heart rate changes without haemodynamic reasons, anxiety, nausea or pain can anticipate late ruptures)3.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE CASE

This challenging case dramatically illustrates the dilemma between the need for anticoagulation therapy in this acute myocardial infarction and the risk of severe bleeding and complete aneurysm rupture favoured by this therapy.

As the patient’s condition involved cardiac surgeons, interventional cardiologists and intensive care unit specialists, we got together with our institution’s Heart Team in the cathlab to decide on a consensual management. As coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) mortality is increased within the first 24 hours of STEMI evolution, our objectives were consequently to open the LAD culprit lesion promptly with minimal anticoagulant support and to propose delayed surgical therapy including myocardial rupture repair+coronary artery bypass. We then opted for a hybrid two-step strategy including minimal PCI with thrombectomy alone followed by deferred surgery.

Left anterior descending artery de-occlusion was performed (Moving image 6) by manual thrombectomy alone (Eliminate™; Terumo Europe, Leuven, Belgium), with an additional 20 mg unfractionated heparin bolus but no anti-GP IIb/IIIa support. TIMI 3 flow was obtained after three passes (Moving image 7), leading to chest pain cessation and regression of ST-segment elevation (Figure 4). No additional stent was implanted, but residual stenosis was observed on the proximal LAD.

Figure 4. Post-thrombectomy ECG control.

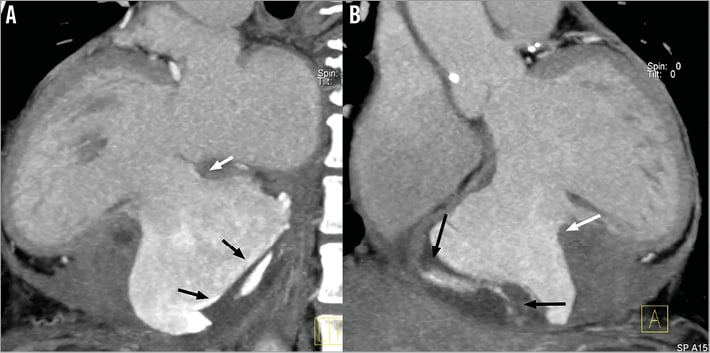

The patient was then transferred to the cardiac care unit in a stable condition. Post-procedural CPK peak was 2,034 IU/L and LVEF was 35%. Computed cardiac tomography was performed and confirmed the presence of a 68×82 mm left ventricle false aneurysm with residual mural thrombus. The aneurysm neck diameter was measured as 40 mm and was surrounded by thinner myocardial scar related to the previous inferior myocardial infarction six weeks before (Figure 5, Moving image 8, Moving image 9).

Figure 5. Cardiac CT scan reconstructions (sagittal views). A) & B) Posterior wall rupture (white arrow) and existence of a large ventricular false aneurysm with presence of abundant mural thrombus (black arrows).

Anticoagulation regimen included aspirin (75 mg/d)+clopidogrel (75 mg/d) for four days then aspirin alone for three days. Cardiac surgery was performed seven days after STEMI onset and included left internal mammary artery to distal LAD CABG+ventricular rupture repair with a pericardial patch under extracorporeal circulation (119 min). The patient was discharged at day 20 and is currently doing fine.

Discussion

Acute myocardial infarction complicated by ventricular rupture is a rare condition associated with poor prognosis. This rupture could involve the interventricular septum or ventricle free wall. This latter location is rarely identified in clinical practice since very few patients survive until the diagnosis can be performed. Hence, in post-mortem examinations, cardiac rupture is present in 30.7% of MI-related mortality4. In most cases, the ruptured myocardial muscle is vascularised by the recently occluded infarct-related coronary artery (IRA). Thus, the present case is highly unusual because of the conjunction of two acute severe cardiac conditions (anterior STEMI and ruptured posterior free wall) that are not obviously related to each other, representing a true therapeutic challenge. Data from the literature regarding the best option for management of this particular situation are very limited. Cardiac surgery is the only reliable solution to treat ventricular free wall rupture, although this method is associated with high mortality when performed during acute STEMI5. On the other hand, standard PCI treatment of the culprit lesion involves stent implantation, prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy and, potentially, use of anti-GP IIb/IIIa agents or bivalirudin6. As we observed echocardiographic signs that could be associated with false aneurysm potential rupture within the pericardium (mural thrombus, mild pericardial effusion), we felt that the anticoagulation strategy widely used in STEMI might worsen the patient’s condition and lead to uncontrollable bleeding and pericardial tamponade.

Although the real benefit of thrombectomy remains debated in an all-comers population7, the use of this technique in STEMI treatment is acknowledged as an effective support to decrease thrombus burden within the culprit lesion8. Previous works reported the feasibility of a deferred stenting strategy following manual thromboaspiration or the use of thrombectomy alone to treat selected patients with acute STEMI9-11. In these series, the rate of reocclusion after thrombus removal was very low and seemed compatible with emergent and safe treatment of STEMI. This approach can be used if the optimal antegrade flow is restored in the IRA and reperfusion is achieved, as witnessed in our case by the TIMI 3 flow grade, regression of ST-segment elevation and cessation of chest pain. This strategy appeared the most appropriate in this situation, as it avoids stent implantation and the need for dual antiplatelet therapy that would have affected cardiac surgery outcome by increasing the bleeding risk12.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Online data supplement

Moving image 1. Initial transthoracic echocardiography: four-chamber view showing apical severe hypokinesia.

Moving image 2. Initial transthoracic echocardiography: two-chamber view, depicting posterior wall rupture and false aneurysm.

Moving image 3. Initial transthoracic echocardiography: parasternal short-axis view, depicting posterior wall rupture and partially thrombosed false aneurysm.

Moving image 4. Coronary angiography showing permeable right coronary artery.

Moving image 5. Coronary angiography showing acute thrombotic occlusion of the distal left anterior descending artery.

Moving image 6. Culprit lesion PCI: thromboaspiration with Terumo Eliminate™ device.

Moving image 7. Initial post-thrombectomy results after three passes, showing restoration of a TIMI 3 flow and mild diffuse spasm.

Moving image 8. Cardiac CT scan animated views confirmed the presence of a large left ventricle false aneurysm with mural thrombus.

Moving image 9. Cardiac CT scan animated views confirmed the presence of a large left ventricle false aneurysm with mural thrombus.