CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 70-year-old female patient with acute inferior myocardial infarction was transferred to our cardiac centre for primary percutaneous intervention. Her chest pain had started two hours before.

INVESTIGATION: ECG and coronary angiography.

DIAGNOSIS: Ostial thrombotic occlusion of the right coronary artery

TREATMENT: Primary percutaneous intervention

KEYWORDS: Myocardial infarction, thrombosis, ostial, angioplasty, thrombectomy

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

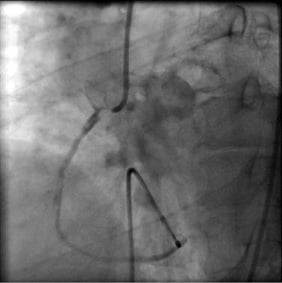

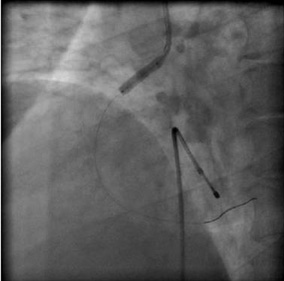

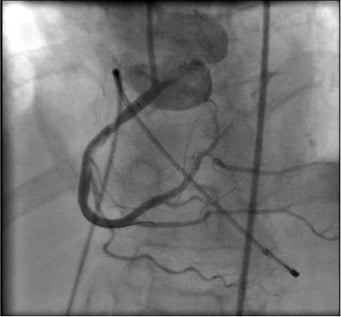

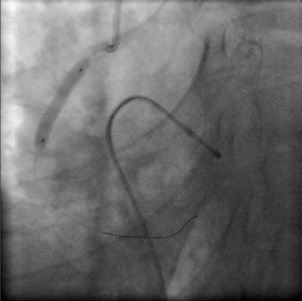

A 70-year-old female patient with acute inferior myocardial infarction was directly (without any pre-hospital thrombolysis) transferred to our cardiac centre for primary angioplasty. The chest pain had started two hours previously and was ongoing. ECG revealed 3rd degree AV block and 2-3 mm ST elevation in leads D2-D3 and aVF with reciprocal ST depression in leads V1-2 and D1-aVL. Right precordial leads also revealed ST elevation proving right ventricular infarction as well. Her past medical history was unremarkable except for poorly controlled hypertension. Blood pressure at presentation was 90/50 mmHg with a ventricular rate of 35-40 beats/minute. The patient was immediately transferred to the catheterisation laboratory, arterial and venous sheaths were introduced and a temporary pacemaker was inserted. Blood pressure measured directly at that point was 85/40 mmHg. Fluid infusion was started. Coronary angiography was performed. There was a middle left anterior descending artery (LAD) stenosis of borderline severity; the circumflex artery (LCx) was unobstructed (Figure 1). At the time of left coronary injection, a thrombus image was suspected at the right coronary artery (RCA) ostium. A diagnostic Judkins catheter was used cautiously to view RCA. The RCA was immediately occluded at the ostium by a large thrombus (Figure 2 and Moving image 1). There was TIMI-1 distal flow. A dissection extending to the mid-RCA was also observed. She had already been given aspirin; clopidogrel 600 mg was loaded and enoxaparin IV was injected. Tirofiban infusion was started.

Figure 1. No significant stenosis in the LAD or LCx.

The RCA ostium was lightly engaged by a side-holed 6 Fr Judkins guiding catheter, again cautiously not to allow deep intubation. A regular floppy guidewire was smoothly passed through the lesion and advanced distally without any dislodgement of the thrombus (Figure 2). At this stage, we considered what could be the most appropriate interventional management of the lesion. There was clearly a risk of antegrade embolisation and no-reflow. However, we were also concerned about retrograde embolisation to the aorta during manipulation of any device in the ostial thrombotic lesion, and then retraction of the device into the guiding catheter. The following alternatives were considered as the first line of management with further intervention to be decided following establishment of antegrade flow and re-evaluation of the lesion:

Figure 2. Large thrombus immediately at the ostium of RCA occluding the RCA flow (Moving image 1).

1. Undersized balloon angioplasty

2. 1-to-1 sized balloon angioplasty with long duration inflation

3. Thrombus aspiration (Export aspiration catheter was available in our centre)

4. Insertion of a distal protection device (availability limited to elective procedures in our centre)

5. Direct stenting (considering also the use of covered stents and mesh covered stents)

6. Intracoronary infusion of a thrombolytic agent.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

This is an interesting case of acute inferior and right ventricular infarction with an advanced AV block caused by a large thrombus at the ostium of the right coronary artery (RCA). Indeed, treatment of haemodynamic instability and appropriate anticoagulation is essential. A large thrombus was observed at the ostium of the RCA with TIMI-1 flow and an abrupt termination of flow in the posterolateral branch. Very likely, this was a sign of a distal embolisation. It is not clear whether a dissection or a filling defect due to slow flow was observed in the RCA.

Although they say that many ways lead to Rome, I do believe there is one optimal approach in this case due to the increased risk of embolisation.

Step one: Advance a floppy guidewire distally. Next, advance a thrombus aspiration catheter with continuous aspiration. If the syringe remains empty, remove the aspiration catheter during continuous aspiration. In case of no retrograde blood flow in the guiding catheter together with the damping of blood pressure curve, attach a large syringe on the side port of the Y connector and try to aspirate blood.

Step two: If the aspiration is not successful, it is very likely that the thrombus has been displaced into the guiding catheter. In that case, remove the guiding catheter during aspiration, followed by rinsing of the catheter.

Step three: After successful thrombus aspiration a control angiogram should follow and thrombus aspiration should be repeated at the site of distal embolisation, if necessary. If this is successful, perform stenting of the diseased segments. You may also chose to stent the proximal RCA, followed by repeated thrombus aspiration at the site of distal embolisation.

In some cases no additional interventions would be necessary after successful thrombus aspiration1. I would not use an undersized balloon, as it has been shown that thrombus aspiration is superior to balloon dilation in primary PCI2. You may consider 1-to-1 size balloon dilation, but this will increase the risk of retrograde embolisation. No benefit of the use of distal protection devices has been shown in primary PCI3. Direct stenting could be considered, however the sizing of the stent would be challenging. Theoretically, covered or mesh stents could decrease the risk of distal embolisation, although the risk of embolisation while crossing the lesion is the same as with direct stenting. Moreover, the side branches would be closed. Small studies showed promising results of intracoronary thrombolysis4, although more evidence is necessary.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERT’S OPINION

This is a complex case in which a large thrombus can be seen in the ostium of the right coronary artery with evidence of distal embolisation and a large dissection extending to the mid vessel in the setting of an acute inferior myocardial infarction. There is a significant risk of further antegrade distal embolisation and no reflow, which is an independent predictor of longer-term mortality in the setting of primary PCI1, as well as the possibility of retrograde embolisation into the aorta. Balloon angioplasty or direct stenting of the thrombus-laden lesion would significantly increase the risk of thrombus embolisation and slow flow/no-reflow. Delivery of equipment distal to the thrombus, such as distal protection devices, would carry a significant risk of distal embolisation as well as the potential to extend the dissection beyond the mid RCA.

I would advocate mechanical thrombectomy with an aspiration catheter (taking care not to extend the mid vessel dissection more distally), since its routine use in the setting of primary PCI has been shown to improve angiographic and ECG markers of myocardial reperfusion in a number of studies2 and the Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous coronary intervention in Acute myocardial infarction Study (TAPAS) has demonstrated a reduction in 1-year mortality3. Intracoronary (IC) administration of the initial IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI) glycoprotein bolus may yield local concentrations high enough to not only inhibit further thrombus formation but to actively disperse thrombi that have already formed. IC GPI has been shown to improve early ST resolution in the Leipzig study4, whilst the CICERO trial5 has demonstrated improved myocardial reperfusion as assessed by myocardial blush grade and a smaller enzymatic infarct size. A recent meta-analysis has also demonstrated improvements in short-term mortality associated with IC GPI compared to IV administration with no difference in rates of bleeding6. If residual thrombus burden remains despite optimal mechanical thrombectomy and pharmacotherapy, isolated case reports have shown intracoronary thrombolytic therapy as an effective treatment option for the management of patients following failed thrombectomy, although this strategy would increase the risk of bleeding complications substantially given the adoption of the femoral access site in this case. Following mechanical and pharmacological treatment of the thrombus, I would then direct stent the proximal lesion with one or more long drug-eluting stent(s) to cover both the proximal lesion and the distal dissection.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF CASE

After passing the guidewire, we decided on direct stenting of the ostial thrombotic lesion. We thought that this option would be the most straightforward approach that would involve the least manipulation in the lesion before it was stabilised. As noted before, we were concerned about retrograde embolisation with use of any device, but particularly with aspiration of the thrombus by the Export catheter. The thrombus was extending immediately to the junction of the ostium and the aorta and any dislodgement during aspiration carried with it the high risk of systemic embolisation. There was no fluoroscopic sign of calcification in the lesion.

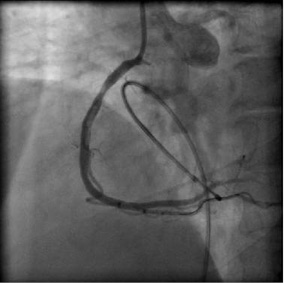

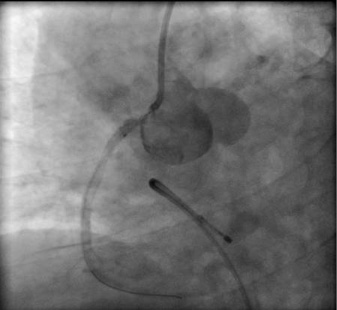

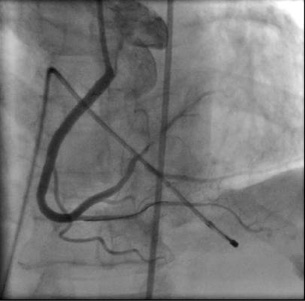

A bare metal stent (4.0×16 mm Gazelle™, Biosensors International, Morges, Switzerland) was implanted at the ostial lesion; care was taken to cover the thrombus completely and also to extend the stent to cover the RCA ostium (Figure 3). The thrombus was covered; however, the exact starting point of the ostium was difficult to assess and was left unstented. No distal embolisation occurred, and TIMI-3 flow was obtained in the RCA (Figure 4). The rhythm converted to normal sinus rhythm. A second stent (4.0×9 mm Gazelle™, Biosensors International) was placed in order to cover the ostium and extend to the aorta 2-3 mm as well as to overlap with the first stent (Figure 5). The result was satisfactory in the ostium (Figure 6).

Figure 3. A bare metal stent is implanted at the ostial lesion.

Figure 4. The thrombus was covered by the stent. The flow in RCA was re-established. However, the result was not optimal at the ostıum of RCA.

Figure 5. A second stent was located as such the ostium of the RCA was covered.

Figure 6. Satisfactory result at the ostium after the second stent.

An embolic occlusion in the distal posterolateral branch was observed after the inflation. Distal to the first implanted stent, at the middle RCA level there was haziness in the lumen. Angiographic appearance, especially in the anteroposterior cranial view, was suggestive of dissection and overlying thrombus. Since there was the impression of dissection and the lesion would be finally stented, we did not attempt thrombus aspiration. A third stent (4.0×23 mm Gazelle™, Biosensors International) was implanted to this segment overlapping with the proximal stent edge (Figure 7). The result was good.

Figure 7. Mid-RCA dissection is treated with a third stent.

Starting from the ostium, the stents and the overlapping segments were further dilated by a non-compliant balloon (4.0×15 mm NC Sprinter RX; Medtronic, Minnneapolis, MN, USA) inflated to the rated burst pressure. The final result was satisfactory (Figure 8). Also, the flow in the distal posterolateral branch improved. The patient was transferred to the coronary care unit. Tirofiban and enoxaparin were continued. At 90 minutes after the procedure, ST-segment elevations were more than 70% resolved suggesting good tissue perfusion. The patient was discharged on the third day of admission without any complications.

Figure 8. Final result after implantation of the three stents and post-dilatation with a non-compliant balloon (Moving image 2 and Moving image 3).

Thrombus aspiration devices have been used increasingly in the setting of acute myocardial infarction to improve distal perfusion1,2. The TAPAS study3 and the results of a meta-analysis4 of the previous studies have demonstrated that use of thrombus aspiration devices is beneficial in primary percutaneous intervention. However, it is not known whether these results can be directly translated to real-life settings. With regard to the lesion characteristics of the presented case, we did not know how safe and efficient was the use of aspiration catheters for ostial lesions. Even with the proximal-to-distal aspiration approach, the thrombus may dislodge proximally during aspiration and then retraction of the aspiration catheter. As long as the thrombus remains within the coronary lumen, this can be tackled by further aspiration. However, proximal dislodgement to the aorta can lead to systemic embolisation. In fact, the meta-analysis of the previous studies worrisomely disclosed a probable increase in the stroke incidence with use of the aspiration catheters4. Some case reports have also reported systemic embolisation complicating thrombus aspiration5. Another potentially catastrophic consequence can be proximal dislodgement of a thrombus from either LAD or LCx to the left main stem, which then jeopardises territories of both arteries6.

Finally, it should be once again underlined that in the TAPAS study direct stenting was not a treatment option. The treatment arms were thrombus aspiration followed by stenting or balloon angioplasty followed by stenting. However, compared to stent implantation following predilatation, direct stenting may also confer a better outcome in the management of acute myocardial infarction. In the recent sub-study of the HORIZONS-AMI trial, compared to stenting following balloon predilatation, direct stenting was associated with significantly better ST-segment resolution at 60 minutes and lower one year all-cause mortality and stroke rates7. Hence, until another study demonstrates that thrombus aspiration followed by stenting is superior to direct stenting in acute myocardial infarction, direct stenting (without thrombus aspiration) should still be regarded as an evidence-based approach. In the presented case with direct stenting, we tried to keep the procedure as simple as possible to promptly restore flow in the RCA without causing any systemic emboli. While no-reflow would not be unexpected in our case, we opted to manage it medically if it had occurred.

It is clear that thrombus aspiration has a promising role in improving tissue perfusion and long-term outcome in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. However, we believe that suitability of the lesions for thrombus aspiration should be assessed individually and risk of proximal dislodgement and systemic embolism should always be considered.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.