CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 76-year-old male admitted for NSTEMI developed symptomatic progression of pericardial effusion. Pericardiocentesis was fluoroscopy-guided and echo-assisted, but the puncture and guidewire insertion were misinterpreted as being in the pericardium and the procedure continued with insertion of an 8 Fr pigtail drainage catheter. Contrast injection disclosed misplacement into the right ventricle.

INVESTIGATION: Pericardiocentesis, angiography, CT exams, 2D echocardiography.

DIAGNOSIS: Misplaced 8 Fr drainage catheter.

MANAGEMENT: Percutaneous sealing with a closure device.

KEYWORDS: cardiac tamponade, closure device, pericardial effusion, pericardiocentesis, right ventricular puncture

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

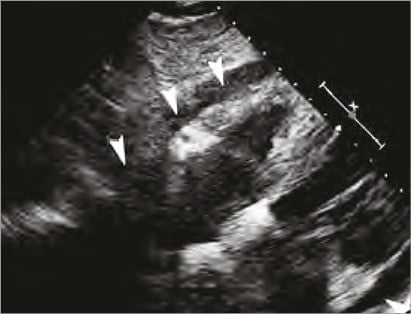

A 76-year-old male with a previous MI, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and asthma was admitted with atypical chest pain. At the admission cTnT was 2,096 ng/L and ECG without changes and 10 mm of symmetrical pericardial effusion was revealed at echocardiography. Thoracic CT excluded aortic dissection and also confirmed the pericardial fluid (Figure 1) beside 4 cm of pleural effusion. Twenty-four hours later echo was repeated due to low blood pressure and shortness of breath. It showed rapid progression of the pericardial effusion adding up to 25 mm in the pericardial sac with a mild systolic compression of the right atrium and right ventricle. Pericardiocentesis and coronary angiography followed immediately. Fluoroscopy-guided and echo-assisted drainage was performed from the subxyphoideal approach (Flexima 8 Fr; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA). During the puncture and guidewire insertion no changes were detected on ECG. The procedure was continued with placement of the pigtail drainage catheter. Contrast injection and saline test were performed and demonstrated a misplaced intracavital position of the drainage catheter within the right ventricle.

Figure 1. Echo on admission showing circumferential effusion in the pericardial space (white arrows).

The pigtail catheter had to be removed, but wouldn’t the large hole inflicted in the right ventricle then continue to fill the epicardial space?

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

Intraventricular placement of a pericardiocentesis catheter is a rare but well recognised event. In a series of 188 procedures over seven years published by Inglis et al, three patients (1.6%) suffered a ventricular puncture1. In other large series, the quoted risk of ventricular perforation with fluoroscopy-guided pericardiocentesis was <1%2.

The early recognition of ventricular perforation may not always be straightforward. Ventricular puncture and catheter placement may be surprisingly well tolerated with little in the way of ECG changes or haemodynamic shift. Final catheter position should always be checked by transthoracic echo and injection of agitated saline through the pericardiocentesis catheter. If there is any uncertainty as to the final position then confirmation should be sought with cross-sectional imaging.

Following confirmation of the pericardiocentesis catheter within the right ventricle, the initial question is whether these patients should be managed in a centre where rapid access to cardiopulmonary bypass and cardiac surgery is available. If the patient is being treated in a non-surgical centre and is haemodynamically stable enough to transfer then we would advocate this approach. The cardiothoracic surgical team should be made aware of the patient with a theatre on standby.

Percutaneous removal of the misplaced catheter under echocardiographic guidance would be the first choice approach in most centres, avoiding the need for general anaesthesia and a surgical procedure. Prior to removal of the drain, any anticoagulation should be appropriately reversed and blood samples sent for cross-matched blood products. Circulating platelet levels should be checked and corrected as necessary. Non-invasive or invasive blood pressure and ECG monitoring is mandatory.

If the pericardial effusion is still present and accessible with ultrasound guidance, we would advocate the placement of a second drain into the pericardial space at the same or alternative site before removal of the primary misplaced drain. This allows absolute control over the pericardial fluid and prevention of tamponade developing. Gentle traction and removal of the misplaced drain under direct echocardiographic guidance should be performed either in the coronary care unit or in an appropriate operating room. It may be necessary to use an appropriately sized guidewire within the pigtail catheter in order to straighten the catheter tip out to aid smooth withdrawal. Echocardiograms should be performed regularly thereafter to ensure there is no rapid increase in effusion size. If a second drain has not already been placed, then further pericardiocentesis equipment should be close at hand in case rapid pericardial tamponade develops.

Passive tamponade of the ventricular perforation is usually enough to seal the defect; however, Petrov et al report an interesting adjunct to percutaneous removal of a misplaced catheter by deployment of a vascular closure device (Angio-Seal™; St. Jude Medical, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to seal the right ventricular perforation with an excellent result3.

If a second pericardial drain is deemed too high risk then a surgical pericardial window could be considered. The ESC guidelines issued in 2004 recommend consideration of a subxiphoid pericardiotomy when a percutaneous pericardiocentesis is relatively contraindicated and in this situation it may be a more prudent strategy4.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

Percutaneous ventricular access was first utilised for diagnostic purposes in the 1950s. More recently, entry into the left ventricle (LV) has been employed for a multitude of structural and congenital heart interventions. The LV is thicker and more muscular than the right ventricle (RV) due to its exposure to high systemic pressures and is potentially a safer site for intervention. Since during systole LV pressure is high and the myocardium is actively squeezing, the puncture site typically closes. In diastole, the intracavitary pressure is relatively low, further minimising the overall likelihood of bleeding. Nonetheless, early complication rates of this technique were high, predominately due to haemothorax from bleeding at the LV puncture site. Contemporary experience of the “off-label” use of nitinol devices to close LV entry has allowed for a more secure approach, especially with sheath sizes greater than 6 Fr5.

The right ventricle, on the other hand, is a thin-walled structure, unable to seal during ventricular systole. Perforation of the right ventricle is a rare occurrence, less than 1% of pericardiocentesis, but can be life-threatening due to continued bleeding and tamponade. Mortality rates associated with venous catheter perforation can be as high as 65%. This case describes an 8 Fr pigtail catheter inadvertently placed into the RV. The question remains whether removal of this pigtail catheter would lead to bleeding into the pericardial space and further haemodynamic compromise. For patients who have undergone prior cardiac surgery, it may be possible that the surgically scarred pericardium can be haemostatic. However, this is not the case for this patient and consideration for closure should be strongly considered.

Options for closure have included both surgery and percutaneous intervention. Early experience of right perventricular access with the placement of a purse-string suture has resulted in successful entry and exit of 7 Fr to 10 Fr sheaths without complication6. Surgical exposure under direct visualisation allows for immediate confirmation of adequate closure. On the other hand, percutaneous options are limited and have required the “off-label” use of currently available devices. Amplatzer Muscular Ventricle Septal Defect and Septal Occluders (mVSD and ASO; St. Jude Medical, Minneapolis, MN, USA) have been reported as permitting successful closure after ventricular penetration with large diameter sheaths7,8. For this case, we would recommend the placement of an 18 mm Cribiform ASO device (St. Jude Medical) as it has a short waist and relatively small length when compared to the mVSD and ASO devices, potentially creating a better seal of the thin-walled RV. A 4 mm ASO device can also be considered with a waist length of 3 mm. Moving image 1 details the steps of ventricular closure (LV in this scenario) with the use of an mVSD occluder. Prior to placement of a device, pericardial fluid should be drained. Positioning with a safety wire in the RV prior to deployment is useful as re-access to the perforation is unlikely.

Conflict of interest statement

C. Kliger has received speaking honoraria from St. Jude Medical. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE CASE

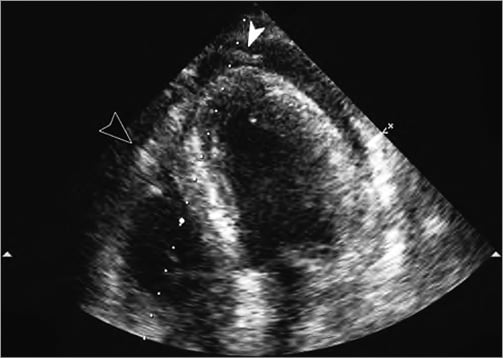

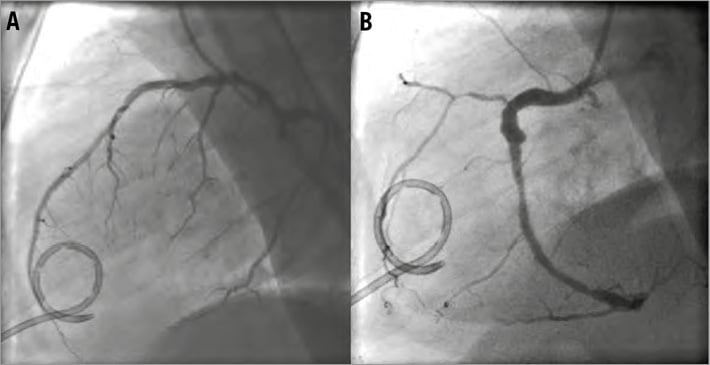

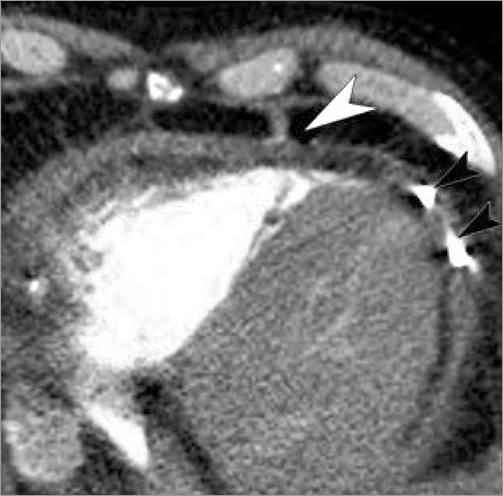

The catheter was retracted over a guidewire and the inflicted 8 Fr catheter hole was sealed with an 8 Fr vascular closure device (Angio-Seal™; St. Jude Medical, Minneapolis, MN, USA) (Figure 2). A new drainage was then correctly placed effortlessly more laterally. Coronary angiography was performed demonstrating no occlusion but a significant stenosis on the first diagonal branch with TIMI 3 flow (Figure 3). No coronary intervention was performed. After the procedure 700 ml fluid was drained from the pericardium. The following day a control CT confirmed the presence of the closure device (Figure 4, Figure 5). After a total of 900 ml of pericardial effusion at day three, the drainage could be removed as no further effusion was detected during the control echo. At day four, fever-elevated inflammatory parameters were observed and diagnosed due to an infection in the urinary tract. The patient was discharged from the hospital at day five in good clinical condition. At one-month follow-up the patient was without symptoms and scheduled for an elective PCI.

Figure 2. Control echo after pericardiocentesis. The drain visualised on the top (white arrow). On the left, the black arrow points to the plug.

Figure 3. Coronary angiogram with the pigtail drainage.

Figure 4. Control CT was performed the next day. The arrow points to the collagen plug. The pericardium is due to the plug being compressed against the heart.

Figure 5. Control CT demonstrating positioning of the collagen plug (white arrow) and the pericardial drainage (black arrows).

Discussion

Drainage of the pericardium carries the risk of perforation of the ventricular wall, but contrast injection and guidewire placement and echocardiography will normally disclose and prevent any misplacement. However, if a large diameter catheter has been inserted into the right ventricle, it can cause a potentially life-threatening situation, should the catheter be removed due to the inflicted large hole in the ventricle, which may lead to open heart surgery. In this case report, sealing of the puncture hole could be performed successfully with a vascular closure device. The distance from the skin to the pericardium needs to be relatively small to allow the tamping tube of the closure device to tighten the self-tightening Roeder knot. Case reports about iatrogenic closing of large artery perforations, such as the brachial, carotid, and subclavian artery as well as the descending aorta with a closure device, have previously been reported3,9-14. In one report a closure device was used in similar circumstances3. These reports suggest that the method can be attempted as a minimally traumatising and potentially life-saving off-label procedure in experienced hands.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Online data supplement

Moving image 1. The steps of ventricular closure (LV in this scenario) with the use of an mVSD occluder.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.