CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 28-year-old woman was admitted for an acute ischaemic stroke. She had a past history of traumatic dissection of the right carotid artery. Because the ischaemic stroke was considered a failure of antithrombotic therapy, we decided to treat the dissecting aneurysm.

INVESTIGATION: CT angiography and conventional angiography revealed a subpetrous extracranial right carotid aneurysm.

DIAGNOSIS: Symptomatic carotid post-dissection aneurysm.

MANAGEMENT: Endovascular therapy. We realised a telescopic implantation of three auto-expandable stents (Carotid WALLSTENT®; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) to exclude the aneurysm.

KEYWORDS: post-dissection aneurysm, carotid stent

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

A 28-year-old woman suffering from schizophrenia was admitted in our department for an acute ischaemic stroke in the territory of the right middle cerebral artery. She had a past history of traumatic dissection of the right carotid artery consecutive to a defenestration seven months previously. She had anticoagulant therapy for three months and thereafter was switched to aspirin due to the formation of a dissecting aneurysm. Because the ischaemic stroke was considered a failure of antithrombotic therapy, we decided to treat the dissecting aneurysm.

The different therapeutic options available to exclude this aneurysm were surgery or an endovascular approach with stenting1-3.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

The problem

Spontaneous or traumatic carotid and vertebral artery dissections are relatively common causes of stroke in young people4. Patients with dissecting pseudoaneurysms are at risk of distal thromboembolism, progressive enlargement leading to vessel occlusion or cranial nerve palsy and bleeding with intracranial or extracranial haemorrhage5. Since the incidence of adverse events is generally low, initial management is conservative with early antithrombotic therapy5,6. If recurrent cerebral embolism or progressive neurological deficits occur, despite adequate medication, aggressive surgical or endovascular treatment is generally warranted.

The treatment

No established consensus about the best treatment exists. Surgical and endovascular approaches are both valuable options. In this case, the distal extension into the skull base would necessitate extensive surgical exposure, and may result in cranial nerve injury or permanent damage of the vessel7. Thus, the treatment options are medical or endovascular therapy.

To be effective, endovascular treatment of symptomatic dissecting aneurysms needs an adequate technique to protect the brain during the procedure, avoiding thrombi dislodgement and embolisation, and an adequate technique to relieve carotid stenosis and exclude the pseudoaneurysm.

The first could be achieved by neuroprotection devices, such as distal filters or proximal protection with flow blockage or inversion. Proximal protection allows complete protection during all phases of carotid artery stenting and also during lesion crossing with the wire. It has shown higher efficacy than filters in reducing silent cerebral embolisation and it should be the first choice in treating symptomatic patients8.

Several techniques have been used to obtain aneurysm obliteration:

– Bare stent: two or more overlapping carotid stents can be used to increase the mesh density preventing clot migration and leading to secondary occlusion of the aneurysm9.

– Stent-assisted coil embolisation: coils are deployed under the stent struts, using the stent as a scaffold that prevents coil migration and dispersion; incomplete occlusion with recanalisation in up to 17% of cases has been reported10.

– Flow-diverter stenting: aneurysm obliteration could be achieved by a flexible, self-expanding nitinol stent with platinum microfilaments specifically designed to produce a haemodynamic flow diversion and to reconstruct laminar flow in the parent artery11.

– Stent grafts: commonly used to repair vascular lacerations, a covered stent deployed across the neck of the pseudoaneurysm could easily fix this problem12,13. Navigation of the stent grafts through the vascular loops can be challenging due to the rigidity of the system, particularly through tortuous, small vessels, or the distal internal carotid artery near the carotid siphon. This may lead to vasospasm, propagation of or new dissection at the ends of the stent, and even vessel rupture. Newly available self-expandable stent grafts are more flexible and have lower profiles to overcome delivery problems. Stent grafts may have a higher rate of thrombosis and restenosis compared to bare stents.

In the present case, the wide-neck aneurysm is located in the distal part of a relatively straight internal carotid artery with a well-developed Willis circle; it probably acts as a source of emboli despite oral anticoagulation. Therefore, a stent graft during endovascular clamping with proximal protection should be used. As an alternative, both flow-diverter and overlapping stents could be attempted, not precluding the use of a stent graft in the case of failure.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

Aneurysms of the extracranial carotid arteries (ECCA) can occur as a result of atherosclerotic degeneration, traumatic injury, dissection, local infection or as a complication after carotid endarterectomy. Extracranial carotid aneurysms are extremely rare compared to carotid atherosclerotic obstructive disease and intracranial aneurysms. Blunt cervical injury and carotid dissection typically involve the distal cervical segment of the internal carotid artery at the skull base.

The symptoms of ECCAs vary according to their location, size and aetiology and can include a pulsatile mass, neurological symptoms, cranial nerve dysfunction, dysphagia, haemorrhage and rupture.

The primary objective in the treatment of such aneurysms is to prevent the permanent deficits that can arise from atheroembolism and thromboembolism. The choice of therapy must be tailored to the individual patient and based on the location, size and cause of the aneurysm. In this particular case the ECCA is considered symptomatic and therapy is warranted14,15.

Open surgical repair

In 1806 Sir Astley Cooper published the first common carotid artery ligation for the treatment of an aneurysm. Hemiplegia resulted on the eighth post-operative day and the patient died 13 days later. Ligation of the internal carotid artery typically results in thrombosis from the level of interruption up to the first intracranial arterial branch, usually the ophthalmic artery. Carotid ligation was previously associated with a 30-60% risk of stroke. Later series show a combined death and stroke rate of 12%. Anticoagulation is probably the key to these improved results. If a carotid artery ligation is considered, preoperative evaluation with a carotid balloon occlusion test and stump pressure measurements is mandatory/necessary. In patients who fail the balloon occlusion test and in whom a ligation is required, an extracranial to intracranial bypass could be considered.

The development of modern reconstructive vascular techniques has eliminated ligation as a standard therapy for ECCA15. Resection of the aneurysm and restoration of flow by an interposition graft (vein or prosthesis) has been the conventional standard of treatment. These surgical options are applicable to lesions involving the common and proximal internal carotid artery, but require further adjuncts to gain distal exposure and control (subluxation of the mandible, resection of the styloid process and distal control with an occlusion balloon).

The long-term results of open surgical reconstructions are usually very good. In general, surgical reconstruction is associated with a combined stroke and death rate of about 10%. Transient cranial nerve dysfunction occurs in about 20% of patients.

Endovascular therapy

The endovascular technique for ECCA involves two options. The technique of transstent coiling initially involves crossing of the aneurysm with a self-expandable stent. Transstent coil embolisation through a microcatheter can then be performed with detachable or platinum coils. The stent prevents migration of the coils into the distal carotid circulation. This technique is mainly applicable in (intra-cranial) saccular aneurysms or pseudo-aneurysms15.

In patients with a fusiform aneurysm, a stent-graft prosthesis (e.g., GORE® VIABAHN® [Gore Medical, Flagstaff, AZ, USA], iCAST™ [Atrium, Hudson, NH, USA], FLUENCY® [Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc., Tempe, AZ, USA] or WALLGRAFT® [Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA]) is a better treatment option12,16,17. In these cases optimal intra- and post-operative anticoagulation is mandatory due to the thrombogenic prosthesis surface.

The early results of endovascular repair of ECCA appear favourable compared to open surgical reconstruction (stroke and death rate around 5%), but there might be a selection bias in the available literature. Secondary interventions might be necessary for endoleaks. The midterm results of endovascular therapy for ECCA show that it is feasible and a durable alternative to conventional open repair.

How would we treat?

Considering the pathology (long lesion) and almost similar diameters proximal and distal of the lesion, our preference in this case would have been the implantation of a newer-generation stent-graft prosthesis (GORE® VIABAHN®). In this particular case we would have had some constraints towards transstent coiling for this long lesion, for thrombogenicity and (micro) embolisms.

A possible alternative could be a multilayer stent technology by Cardiatis (Isnes, Belgium). However, considering the lack of strong evidence with this device, age and critical lesion in this patient, we would be rather reticent about this technology.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE CASE

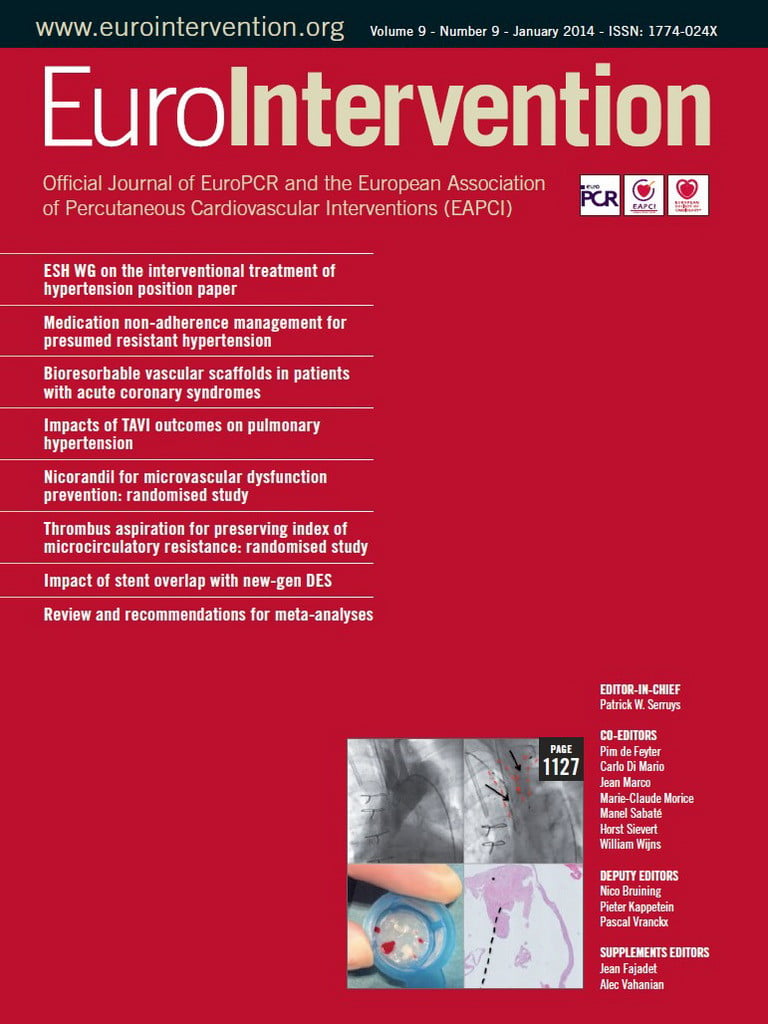

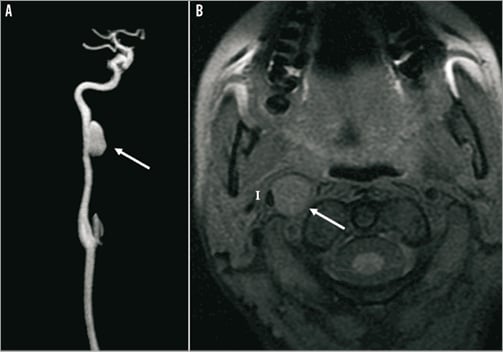

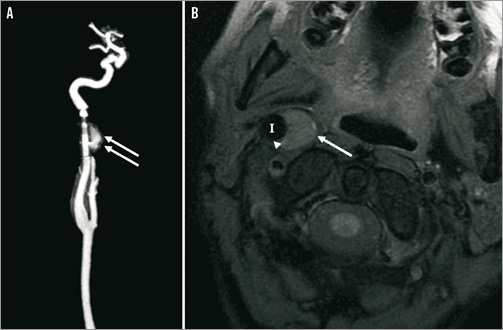

We decided to exclude the aneurysm by endovascular treatment since surgery was complex due to the localisation of the aneurysm. We realised a telescopic implantation of three auto-expandable stents (Carotid WALLSTENT®; Boston Scientific) to exclude the aneurysm. MR scans (A: gadolinium enhancement and B: T1 Fat Sat) show the evolution of the aneurysm before (Figure 1), one month (Figure 2) and six months (Figure 3) after the telescopic implantation. Note the progressive disappearance of the aneurysm (arrows), with a persistent leak at one month (Figure 2A, double arrows) and the enlargement of the internal carotid artery (I) lumen after stent implantation (Figure 2B, arrowheads).

Figure 1. MR scans (A: gadolinium enhancement; and B: T1 Fat Sat) show the presence of the post-dissection carotid aneurysm appearing as a round isointense structure (arrow), which has a mass effect on the carotid artery lumen (I).

Figure 2. MR scans (A: gadolinium enhancement; and B: T1 Fat Sat) showing the evolution of the aneurysm one month after the telescopic implantation of three auto-expandable stents. Note the reduction of the aneurysm size (arrow), with a persistent leak (double arrows) and the enlargement of the internal carotid artery (I) lumen after stent implantation (arrowheads).

Figure 3. MR scans (A: gadolinium enhancement; and B: T1 Fat Sat) showing the disappearance of the aneurysm and the leak six months after the stenting (arrow).

No periprocedural complication occurred and the patient remained free from any new neurological symptoms. The patient received dual antiplatelet therapy for six weeks and aspirin 75 mg thereafter.

The endovascular approach may be an alternative treatment for symptomatic chronic dissecting carotid aneurysm while on antithrombotic therapy.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.