Abstract

Aims: Carotid artery stenting (CAS) is still associated with higher periprocedural cerebrovascular events (CEs) compared to vascular surgery. The Roadsaver carotid artery stent is a double layer micromesh stent which reduces plaque prolapse and embolisation by improving plaque coverage. Its clinical impact on neurological outcome was unknown. The aim of this study was therefore to report the clinical results of a large real-world population from three different centres receiving a Roadsaver stent to treat carotid artery disease.

Methods and results: One hundred and fifty (150) patients (age 74±8 yrs, 75% male, symptomatic 29%) treated with CAS using the Roadsaver carotid stent in three high-volume Italian centres were included in the study. Intraprocedural optical coherence tomography (OCT) evaluation was performed in 26 patients, with an off-line analysis by a dedicated core laboratory. All patients underwent duplex ultrasound and neurological evaluation at 24 hours and at 30 days. CAS was technically successful in all cases (stent diameter: 8.6±0.8 mm, stent length: 25.0±4.5 mm). No in-hospital or 30-day CEs were observed. OCT evaluation detected a low rate of plaque prolapse (two patients, 7.7%). Duplex ultrasound showed stent and external carotid artery patency in all cases both before discharge and at 30-day follow-up.

Conclusions: The Roadsaver stent is a safe and promising technology for CAS, with a low percentage of plaque prolapse and good short-term clinical outcome. Larger studies with longer follow-up are necessary to confirm this favourable clinical outcome.

Abbreviations

CAS: carotid artery stenting

ECA: external carotid artery

ICA: internal carotid artery

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

OCT: optical coherence tomography

TIA: transient ischaemic attack

Introduction

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) is a safe and effective option to treat internal carotid artery (ICA) disease. Its clinical outcomes have been shown to be not inferior to surgical endarterectomy in a large number of studies with mid to long-term follow-up1-4. However, looking critically at clinical results obtained with CAS, a higher rate of 30-day cerebrovascular events compared to surgery has been reported5-7. Subsequently, every effort has been made to try to reduce procedure-related events that could influence neurological outcome. Distal embolisation is the major neurological complication occurring after CAS, not only periprocedurally but also in the first 30 days8. Embolic protection devices have now gained widespread diffusion since they have shown a favourable effect on clinical outcomes9. However, published data have revealed that cerebrovascular embolisation is not limited to procedural time10. The timing of stroke occurrence has suggested a role for the power of plaque retention by carotid stents in determining clinically relevant embolic events: after CAS the carotid plaque is retained by the scaffolding and wall-coverage properties of the stent, and the risk of plaque prolapse and distal embolisation is definitely influenced by stent geometry11. Actually, open-cell stents seem to be related to a higher risk of embolisation12, but until now clinical results have been conflicting and not definitive13.

The need for sustained embolic protection has led to the emergence of new dual-layer stents able to increase plaque coverage and subsequently reduce the risk of debris dislodgement through the stent struts, possibly by maintaining stent flexibility and conformability. The Roadsaver® carotid artery stent (Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan) has been designed to increase plaque coverage with its dual-layer design without losing the anatomical flexibility that can be useful in treating all types of lesion. It has been introduced into clinical practice and encouraging clinical results have been shown in a small population of patients14; however, no data about its real clinical effectiveness in everyday life are currently available. The aim of this study was therefore to report the clinical results of a large real-world population from three different centres receiving a Roadsaver stent to treat carotid artery disease.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

The study population comprised all consecutive patients who underwent CAS and received a Roadsaver stent between October 2014 and October 2015 in three high-volume Italian centres performing CAS with a different specialty background: Interventional Cardiology Unit of Maria Cecilia Hospital (Cotignola, Italy); Vascular Radiology Unit of San Giovanni Battista University Hospital (Turin, Italy); Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Unit of Siena University Hospital (Siena, Italy).

Patients were prospectively included in the registry if they were at least 18 years old and if they had evidence of a symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Patients were considered symptomatic if they had evidence of an ipsilateral TIA or stroke within the previous six months15. Symptomatic patients had to have a stenosis ≥50% as evaluated on duplex ultrasound; for asymptomatic patients the stenosis had to be ≥80% and suitable for treatment according to vascular and neurological specialists.

The main exclusion criteria were carotid obstruction or the presence of endoluminal thrombus, previous stenting in the same site, acute stroke within the last 30 days, myocardial infarction within 72 hours, intracranial haemorrhage in the last 12 months, bleeding or coagulative disorder and contraindication to antiplatelet therapy.

The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and patients gave written informed consent for the procedure.

REVASCULARISATION PROCEDURE

The choice of the revascularisation strategy regarding access site, neuroprotection device (proximal vs. distal), guiding catheter and length of stent was left to the operator. The agreed guiding criteria to decide when to implant a Roadsaver stent were the presence of a “soft” plaque at duplex baseline assessment and/or a high-risk carotid plaque (symptomatic patient or angiographic evidence of complicated plaque, including ulceration, dissection, etc.). Although all operators were from different areas of expertise, a tailored approach to each patient’s lesion and anatomy was used in every centre16. ICA tortuosity was acknowledged in the presence of any ripple or elongation in an “S” or “C” fashion17.

All patients were on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg/day) for at least three days before the intervention and until four weeks afterwards. Revascularisation procedures were performed through the transfemoral or transradial approach under local anaesthesia, with systemic heparinisation and 6 Fr-10 Fr introducers. Routine cerebral protection was attempted by a proximal (Mo.Ma Ultra; Medtronic Invatec, Roncadelle, Italy) or distal (FilterWire EZ™; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA or SpiderFX™; ev3, Inc., Plymouth, MN, USA or RX Accunet®; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) embolic protection device.

After positioning of the protection device, Roadsaver stents were implanted with or without balloon predilation. Post-dilation was performed with coronary balloons.

Procedural success was defined as successful ICA stenting under proximal or distal neuroprotection with achievement of residual stenosis of less than 20% by visual estimation.

OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY (OCT) STUDY

OCT images were acquired after stent deployment in a subgroup of patients. Both patients who received a distal filter and those with proximal neuroprotection underwent OCT evaluation according to different protocols which have been described elsewhere18,19.

Cross-sectional OCT images within the stented segment of the ICA were evaluated at 1 mm intervals for the presence of plaque prolapse. Plaque prolapse was defined as any appreciable tissue prolapse between the stent struts.

CLINICAL OUTCOME ASSESSMENT

An independent neurologist performed a neurological examination before and after the procedure using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

Patients were scheduled to undergo clinical and duplex ultrasound evaluations at baseline, at 24 hours from the procedure and at 30 days after CAS to assess stent patency and external carotid artery (ECA) patency.

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) was defined as focal brain ischaemia with resolution of symptoms within 24 hours after onset. Stroke was defined as a new neurological deficit of sudden onset with focal symptoms and signs consistent with focal ischaemia lasting at least 24 hours in the absence of primary haemorrhage, which was not explained by other causes (e.g., cardiac embolism, trauma, infection, or vasculitis). Stroke was considered minor if the neurological deficit resolved completely within 30 days or did not lead to a functional impairment in daily activities.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages and analysed with Fisher’s exact test, whereas continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation. A p-value <0.05 was planned to be considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, Version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

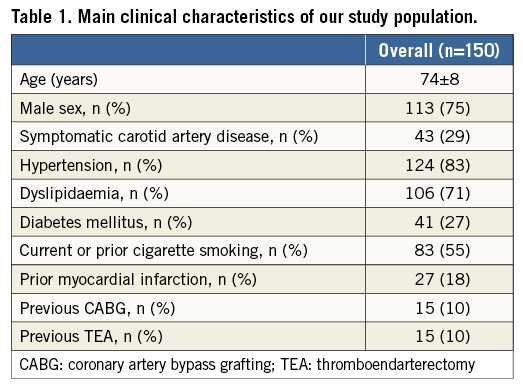

A total number of 167 patients were potential candidates for Roadsaver implantation. Of these, 150 patients (age 74±8 yrs, 75% male) definitely received a Roadsaver stent and were included in the registry. The main clinical characteristics of enrolled patients are reported in Table 1. In spite of a considerable prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and a previous cardiac history, most treated patients had an asymptomatic ICA stenosis (n=107, 71%).

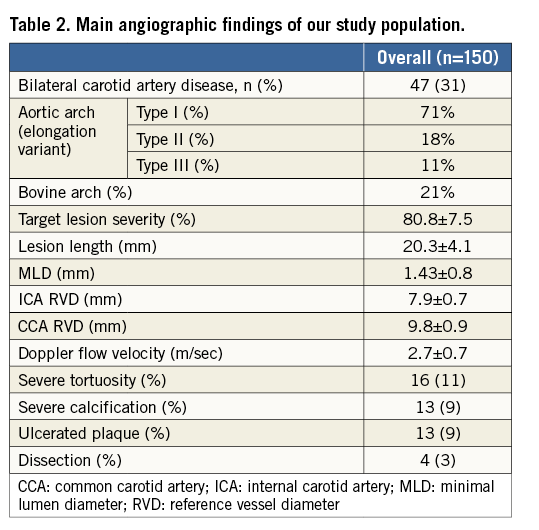

All patients had evidence of a “soft” plaque at duplex assessment. The angiographic characteristics of the patients are summarised in Table 2. Of note, CAS was performed in a wide range of anatomic aortic arch variants, with 11% of procedures performed in the presence of a type III elongated arch and 21% in a bovine aortic arch.

An ulcerated plaque, as assessed by selective ICA angiography, was present in 9% of the patients.

PROCEDURAL RESULTS

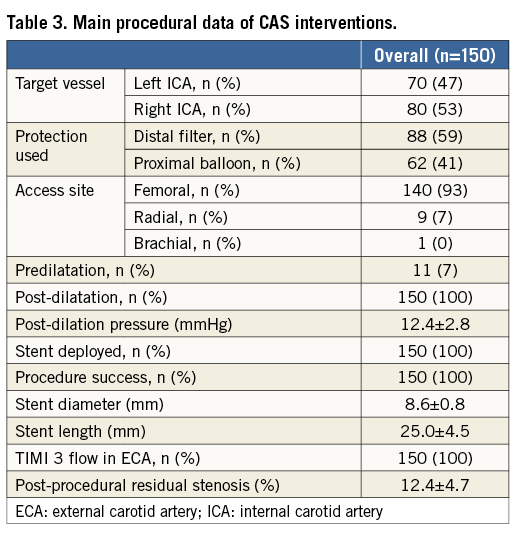

Table 3 summarises the main CAS procedure data. Procedural success was obtained in all patents.

Proximal protection was used in 62 patients (41%), whereas distal protection was used in 88 patients (59%). Proximal neuroprotection was preferred in case of symptomatic status, since it was performed in 35 symptomatic patients (82%). In five patients treated with proximal protection (8%), some potentially embolic debris was aspirated; no patients treated with filter had evidence of any material in the device.

The treated lesions were relatively short (mean stent length: 25±4.5 mm) and predilation was performed in only 11 patients (7%). No patients had evidence of plaque prolapse at angiography.

The final angiographic result was good in all patients, including in those with ICA tortuosity.

No access-site vascular complication was reported. No cerebrovascular event occurred during the procedure.

OCT RESULTS

OCT was performed in 26 patients (17.3%) and was not driven by the presence of any plaque prolapse at post-stenting angiography. OCT was obtained with proximal protection in 11 cases (42.3%), whereas the other 15 patients (57.7%) had an OCT assessment with a distal protection device.

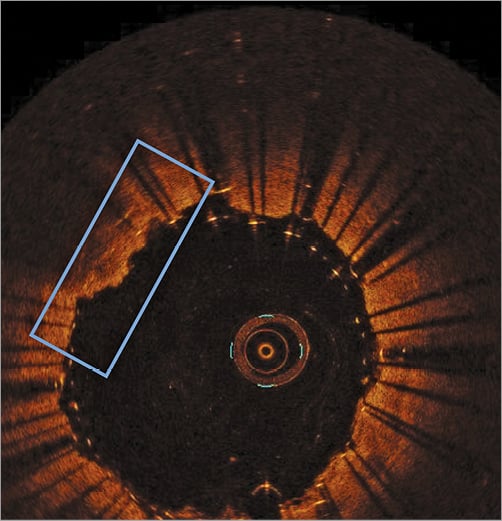

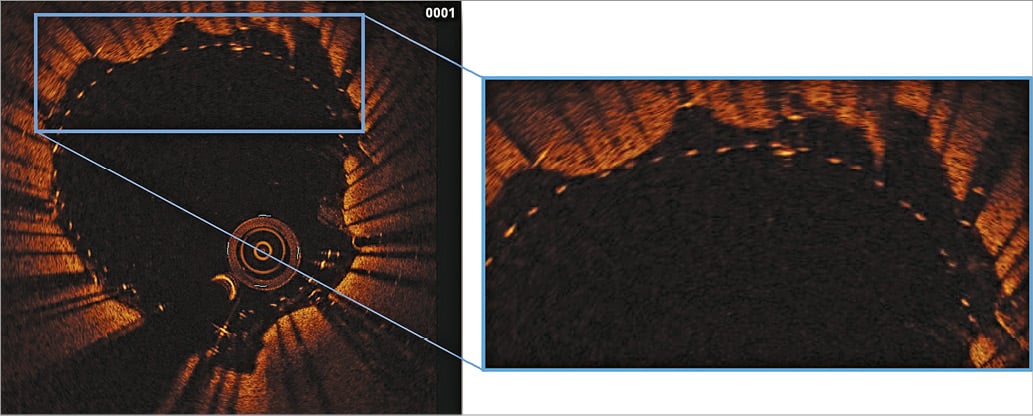

Some mild plaque prolapse was detected in only two patients (2/26, 7.7%) (Figure 1). Both patients had a “soft” lesion at preliminary Doppler assessment. However, in both cases no further treatment was performed. The majority of patients had evidence of plaque protrusion from the inner layer of the stent (15/26, 57.7%), but plaque material never went beyond the second row of struts (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Plaque prolapse (2/26, 7.7%). Evidence of some plaque material protruding out of the two layers of struts of the Roadsaver stent.

Figure 2. Plaque entrapment between stent layers (15/26, 57.7%). Evidence of carotid plaque material between the two Roadsaver layers but not beyond the inner row of struts.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

All patients were discharged without any major vascular complication. At the 24-hour and 30-day ultrasound examination, ECA was patent in all cases; all ICA stents were patent without in-stent restenosis. No cerebrovascular event was reported either at discharge or at 30-day follow-up assessment. Patients’ compliance to dual antiplatelet therapy at 30-day follow-up was 100%.

Discussion

CAS has shown clinical results comparable to surgery except for the earlier periprocedural phase20. Actually, stent scaffolding properties and wall coverage are associated with 30-day neurological events in patients with high-risk plaques treated with CAS, with a proportional relation between complication rate and free cell area21. New dual-layer stents have been introduced into clinical practice in order to help increase plaque coverage and decrease the risk of debris dislodgement through the stent struts. Preliminary results of the CGuard™ stent (InspireMD, Boston, MA, USA), a novel mesh-covered carotid stent, have been favourable22, while data supporting clinical outcome with the Roadsaver stent are currently scarce14.

This is the largest published population of patients treated with CAS receiving a Roadsaver stent. Our registry put together experience from different areas of expertise (interventional cardiology, vascular radiology, vascular surgery) with a high volume of procedures and the common purpose of choosing a CAS strategy according to patient and lesion characteristics.

The main findings of our study are the following:

1. The Roadsaver stent is safe and can be deployed easily in a wide variety of anatomies and lesions by expert operators performing CAS in high-volume centres.

2. Plaque prolapse, as assessed by OCT, is relatively low with this novel device.

3. 30-day clinical outcome is good after Roadsaver stenting with neuroprotection.

Current evidence shows that CAS is a reasonable alternative to surgical endarterectomy for a high proportion of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients only if performed in experienced high-volume centres23. Our decision to include in our registry data from CAS procedures performed by three different types of specialists was aimed at providing a faithful snapshot of the real-world best treatment options currently available. Our results show that the Roadsaver stent can be easily and safely deployed in all patients, independently of aortic arch anatomy and the presence of proximal or distal neuroprotection devices and in a mixed population of both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Of note, we report a 100% procedural success with ECA patency (confirmed at 30 days) in all cases and no intraprocedural adverse events. This confirms the success of a tailored CAS procedure implying the choice of a specific neuroprotection device according to the patient’s anatomy in order to minimise embolisation during the procedure24,25.

Our data, although obtained in a non-randomised series of real-world patients, report a favourable short-term outcome after CAS procedure using the Roadsaver stent, with no cerebrovascular event described at 30-day follow-up. These results are in line with the good outcome observed in the CARENET trial at 30-day follow-up: no clinical event was reported after CGuard stenting, with all but one periprocedural lesion assessed at weighted MRI completely resolved at one month22. Furthermore, recently published data from the CLEAR-ROAD confirmed (in a prospective and solid design) the good clinical result of the Roadsaver stent in the periprocedural phase26.

Since for both stents the exact relation between stent design and outcome could be only postulated, we performed OCT assessment in a small subgroup of patients: we found a low percentage of plaque prolapse beyond the two layers of struts (2/26 studied patients). OCT is a helpful tool to evaluate the results of carotid stenting using both an occlusive and a non-occlusive technique27. Although no definite data are available, the prevalence of plaque prolapse after CAS, as assessed by OCT, has been estimated between 29% for closed-cell design and 69% for open-cell design18. In addition, a higher incidence of plaque prolapse has been described in patients with lipid-rich plaques28. This is definitely the most suitable population to receive a Roadsaver stent. The clinical usefulness of these values is still debated but, since the use of a dual-layer stent has been advocated in order to reduce plaque material prolapsing between stent struts, measuring the amount of plaque prolapsing from the struts should be mandatory. Actually, our data suggest that only 8% of patients showed a small plaque protrusion, which, in any case, was not clinically relevant. Of note, in the vast majority of cases plaque material was entrapped between the two layers of struts, thus explaining the sustained antiembolic action of the stent up to 30-day follow-up.

Study limitations

Our results should be interpreted cautiously because of a number of limitations of the present study. First, the lack of randomisation and the absence of a control group could have resulted in a low-risk population receiving a Roadsaver stent, which could be partly confirmed by the higher proportion of asymptomatic patients. In this population, our results are definitely in keeping with recent data showing that in asymptomatic patients CAS is a safe and effective alternative to endarterectomy29. However, the decision to deploy a Roadsaver stent was usually driven by the presence of a “suitable” lesion at duplex assessment (“soft” plaque) more than by the patient’s risk profile. In fact, this should be considered as the real setting for use of the Roadsaver stent, with a stronger emphasis on the need for an accurate CAS strategy in the different patients than on the use of a specific stent for all cases16. Nevertheless, the absence of a routine brain functional test at follow-up could have prevented the detection of subclinical cerebrovascular events possibly related to distal microembolisation after CAS. Second, the impossibility of assessing by OCT all implanted stents could have resulted in the selection of a subgroup of patients in whom procedural success was quicker and easier, thus possibly reflecting the presence of a lower-risk lesion. However, the absence of any plaque prolapse at angiography should confirm that patient selection was not a key factor in the OCT results.

Conclusions

The Roadsaver stent is a safe and promising technology for CAS with favourable short-term clinical outcome. OCT showed a low percentage of plaque prolapse after Roadsaver stenting, which could partly explain the lack of clinically relevant embolic events at 30 days. Larger prospective studies with longer follow-up will be needed to confirm this favourable clinical outcome and the role of plaque prolapse as assessed by OCT in determining short-term embolic cerebrovascular events.

| Impact on daily practice The Roadsaver double-mesh carotid stent has recently been introduced into clinical practice. This study represents the largest real-world population receiving CAS with the Roadsaver: procedural results were good in that they showed stent safety and effectiveness on the lesion independently of the strategy and the specialty-related experience of the operator. OCT analysis after stent deployment showed a low percentage of plaque prolapse. Stent safety was confirmed at 30-day follow-up when no clinically evident cerebrovascular events were reported. Roadsaver stent implantation should be strongly considered in patients with an adequate risk profile and suitable carotid lesions. |

Conflict of interest statement

F. Castriota, A. Micari and A. Cremonesi have received consultancy fees from Terumo though not in relation to the present article. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.