CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 60-year-old man with a history of previous coronary artery bypass grafting (saphenous vein grafting [SVG] to native right coronary artery [RCA] and sequential left internal mammary artery [LIMA] jump grafting to his native first diagonal [D1] and left anterior descending [LAD] arteries), who had developed a previous ischaemic cerebrovascular accident following femoral angiography, re-presented with further ischaemic cardiac symptoms.

INVESTIGATIONS: Physical examination, electrocardiography, biochemistry including high-sensitive troponin, echocardiography, and trans-radial angiography.

DIAGNOSIS: Severe native 3 vessel disease including ostial occlusion of the LAD, distal left circumflex and obtuse marginal (LCX/OM) disease and proximal RCA occlusion; occluded SVG to RCA, and evidence of a critical stenosis in the mid LAD distal to the insertion of the tortuous LIMA jump graft (diagonal to LAD).

TREATMENT: PCI to mid LAD lesion via LIMA jump graft from left trans-radial approach.

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

A 60-year-old man presented to the emergency department following an episode of severe chest pain and breathlessness. During his initial work-up he developed ischaemic ventricular fibrillation (VF), from which he was successfully resuscitated.

His past medical history included treated arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, type 2 diabetes, and permanent atrial fibrillation (AF). He had also undergone previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in 1994, with saphenous vein grafting (SVG) to native right coronary artery (RCA) and sequential left internal mammary artery (LIMA) jump grafting to his native first diagonal branch (D1) and left anterior descending artery (LAD).

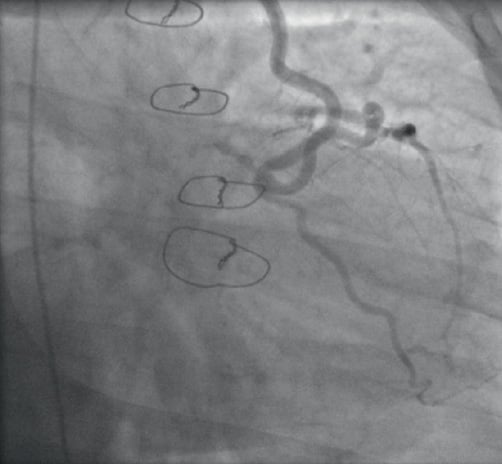

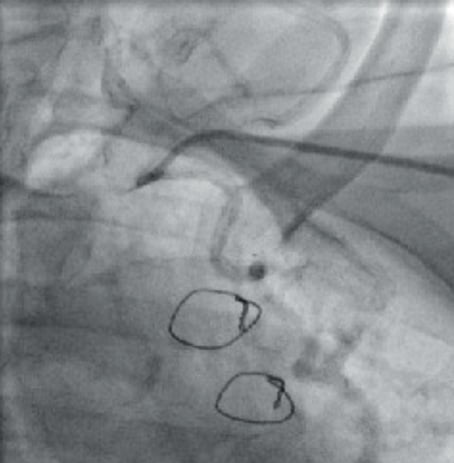

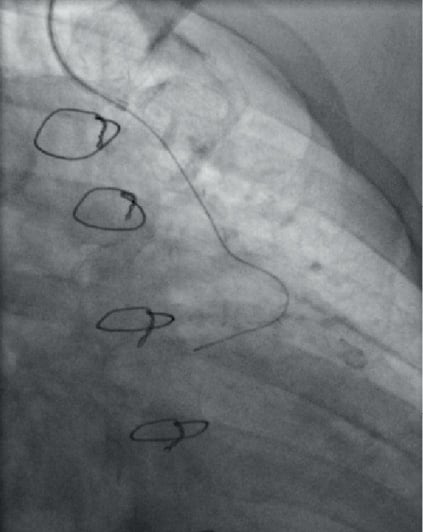

He had presented with similar symptoms in 2010, and underwent angiography and graft study from the right femoral approach (RFA). This showed severe native 3 vessel disease including, ostial occlusion of the LAD, distal left circumflex and obtuse marginal artery (LCX/OM) disease and proximal RCA occlusion. The only remaining functioning bypass graft was a sequential LIMA jump graft to LAD and D1. He was also found to have a severe stenosis in the mid LAD distal to the insertion of the tortuous jump graft (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1. Tortuous LIMA jump graft from D1 to LAD.

Figure 2. Critical stenosis in the mid LAD distal to the insertion of the tortuous LIMA jump.

Unfortunately, the procedure was technically difficult due to vascular tortuosity and difficulty engaging the IMA origin, and was complicated by an acute ischaemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA) with development of a dense right-sided hemiparesis. Consequently, medical management of his coronary artery disease (CAD) was chosen at that time, including aggressive secondary prevention. He made a slow but excellent recovery from the CVA with mildly reduced power in his right upper limb (power 4/5).

His presenting electrocardiogram (ECG) at the time of the acute presentation showed AF with 2 mm ST depression and T wave inversions in the anterior leads (V1-6). His blood tests revealed a potassium level of 3.3 mmol/L and high sensitivity troponin (Hs-trop) was elevated at 101 ng/l. He was treated with loading doses of aspirin and clopidogrel (300 mg each). His international normalised ratio (INR) was therapeutic (>2) so no further anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was given. Echocardiography revealed mild septal hypokinesia with preserved LV systolic function (LVEF 50%) and no significant valvular abnormalities.

His case and previous angiogram were reviewed at multidisciplinary heart team meeting and the treatment options were discussed.

Repeat surgery was considered high risk on the basis of his EuroSCORE (10), his previous stroke, and his total coronary reliance on the existing LIMA graft. Femoral angiography had previously resulted in a cerebrovascular accident, most likely from torquing the catheter repeatedly in search of the LIMA origin, and the angle between the LIMA and left subclavian artery was >130 degrees and therefore not optimal for the trans-radial approach (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Extreme angle between the left subclavian artery and the LIMA take-off.

The patient was not keen for repeat percutaneous intervention from the femoral approach because of the previous complication. Therefore, it was felt that the lowest risk strategy would be attempted PCI to the mid LAD lesion via the LIMA jump graft from the left radial access route despite the acute angulation between the IMA and the subclavian artery.

Two major difficulties were envisaged. Firstly, engagement of the LIMA graft from the left subclavian, given the acute angle involved, and secondly delivering a balloon and stent around the tortuous curves of the LIMA to the diagonal vessel and from there to the LAD and across the lesion.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

The case presented is one of a high-risk patient with unstable symptoms, troponin elevation and a tight stenosis of the native left anterior descending coronary artery after the anastomosis of a left internal mammary artery (LIMA) jump graft, which is the last remaining vessel. Patients requiring secondary revascularisation frequently present more risk factors and hence diffuse disease.1,2

In this complex scenario, a number of difficulties have to be addressed, as were suggested by the treating team. It is entirely reasonable to reconsider a percutaneous approach, taking into consideration that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) often remains the revascularisation method of choice in view of the high risk associated with redo-surgery.3

Regarding the use of haemodynamic support devices, as the patient has preserved left ventricular systolic function, we would not use electively an intra-aortic balloon pump.4 However, it is important to ensure this is immediately available, if required.

The left radial artery would be our access of choice, with a standard 6 Fr sheath considering the difficulties in engaging the LIMA encountered in the prior attempt. In such a case, as adjunctive therapy we would use unfractionated heparin.

As for the guiding catheter we would use, in the first instance, an internal mammary artery (IMA) catheter. If this proved difficult, we would change to an IMA diagnostic catheter which can be easier to manipulate. Following this, one or two 0.014” coronary guidewires could be passed into the LIMA, before exchanging for a guiding catheter. The coronary guidewires of preference would be hydrophilic, as two standard guidewires in a diagnostic catheter may provide too much friction. The alternative option is to use a Bartorelli-Cozzi (Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA) diagnostic catheter, which is specifically designed to engage the LIMA from the left radial artery and, again, utilise two coronary guidewires to exchange for the guiding catheter.

Once the LIMA has been engaged, we would continue to work with two guidewires, one across the lesion and one in the LIMA for extra support in view of the extreme tortuosity. We would then proceed to adequately pre-dilate the lesion and aim to implant a stent as short as feasible. The choice of stent is important, as the patient has chronic atrial fibrillation, possibly requiring chronic anticoagulant therapy. However, the patient is diabetic which increases the likelihood of restenosis. Taking these factors into account, we would choose a drug-eluting stent with good trackability and flexibility, such as the Promus Element (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA). It is increasingly suggested that only three months of dual antiplatelet treatment may be sufficient following everolimus-eluting stent implantation with Xience V® and Xience Prime™ (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) stents, which recently received CE mark in Europe for this indication.

If the tortuosity proves too much to allow the passage of a stent, a further strategy that could be employed is the use of the GuideLiner (Vascular Solutions Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) which may improve visualisation and stent delivery. An alternative solution would be to use multiple short stents (8 mm lengths), which have proven to be very trackable.

Finally, it is important to be aware that severe spasm may occur in the LIMA graft, therefore intracoronary nitrates should be used liberally throughout the procedure. The spasm may lead to reduced visualisation, and it is imperative that the PCI is performed quickly as the LIMA does not tolerate hardware for long periods. Indeed, it may be necessary to remove the wires if significant severe spasms occur with the hope that this will settle with ample intracoronary nitrates.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this manuscript.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERT’S OPINION

The present case offers several challenges during a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the mid-left anterior descending (LAD) coronary arterial lesion. When approaching the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft via left trans-radial access, there is an acute angle between the subclavian artery and the LIMA. The steep angle causes a non-coaxial orientation of the guide inside the LIMA ostium which hampers wiring and increases the risk of a LIMA dissection that could be life-threatening, considering the status of the coronary system. The extreme tortuosity of the LIMA will then render the passage of balloon catheters and stents into the LAD difficult. In such challenging anatomical situations, an excellent back-up of the guide catheter is of paramount importance. In the present case, with the difficult engagement of the LIMA, however, it is unlikely that an excellent back-up of the guide can be assured by conventional means. While larger diameters of the guide and stiffer guidewires can theoretically increase back-up, in the present case, the radial access route and the LIMA tortuosity will limit such options. In addition, deep intubation of the guide1 will be difficult and associated with an increased risk of dissecting the proximal segment of the LIMA.

I would, therefore, start wiring the LIMA graft with a flexible guidewire with a hydrophilic coating, after administration of adequate doses of heparin and intracoronary nitrates. I would then opt for up-front use of the GuideLiner catheter (Vascular Solutions Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), a rapid exchange guide catheter extension system that is used to improve both support and coaxial alignment of the guide2-5. I would try to advance the flexible tubular end of the GuideLiner deeply into the LIMA. While the distal tip is relatively soft, there is still a low residual risk of dissecting vessels that one should be aware of. Use of a buddy wire may help to advance the GuideLiner safely and could also be useful for the further treatment steps, such as advancing balloon catheters and finally a stent.6

An additional challenge, that should not be underestimated, is the nature of the LAD lesion. The lesion is located just distal to the LIMA anastomosis. Because of the close proximity between lesion and anastomosis, stenting is likely to involve the fibrous, rigid segment of the anastomosis. The first two challenges (difficult engagement and extreme tortuosity of the LIMA) are likely to augment difficulties in advancing a stent into the mid-LAD lesion. Sufficient lesion preparation can significantly facilitate the procedure and may be mandatory in the present case.

For that reason, I would first carefully pre-dilate the lesion with an adequately sized balloon catheter at pressures of at least 14 atm, resulting in an adequate balloon expansion. In the case of this relatively young diabetic patient with very advanced coronary artery disease, I would certainly choose to implant a drug-eluting stent (DES) despite the chronic oral anticoagulation therapy. The fact that the patient experienced ventricular fibrillation during clinical workup underlines the vital importance of maintaining patency of the LIMA. In such challenging cases, operators tend to use stents with favourable clinical performance that are well known to them. In the present case, I would select one of the novel third-generation DES that were designed to improve stent deliverability and are available in our catheterisation lab.7 I would avoid stent undersizing and generally implant the stent at 14-16 atm (and sometimes even 18 atm). In a well pre-dilated lesion, stenting with such pressure can result in a very favourable angiographic result, even without postdilation. However, in case of stent waisting, I would post-dilate the stent with a modern, non-compliant balloon catheter at pressures of at least 20 atm, as is often performed in our centre in both clinical trials and routine clinical practice.8,9

At the end of the PCI, I would carefully withdraw the GuideLiner from the LIMA, visualise the proximal LIMA segment in two angiographic projections, and then, in the absence of a dissection, pull the guidewire out of the LIMA to finish the procedure after a last documentation of the final angiographic result.

Conflict of interest statement

The author is a consultant to Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic and has received a lecture fee from MSD.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF CASE

Left radial access was achieved (6 Fr) and a weight adjusted dose of heparin given. An IMA guide catheter would not engage the ostium of the internal mammary artery, as expected. Attempts were made to “remote wire” the LIMA ostium using hydrophilic coronary guidewires with both an acute bend, and also a hairpin bend, as is used sometimes to access difficult side branches within the coronary circulation.1 These wires however passed only an inch into the LIMA before prolapsing (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Backward angled curve on the guidewire enabling the first inch of the wire to enter the LIMA.

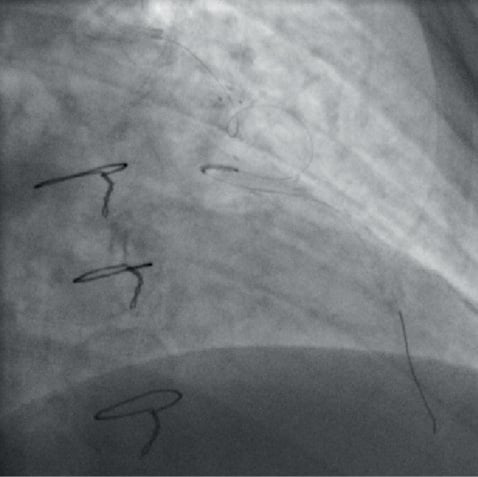

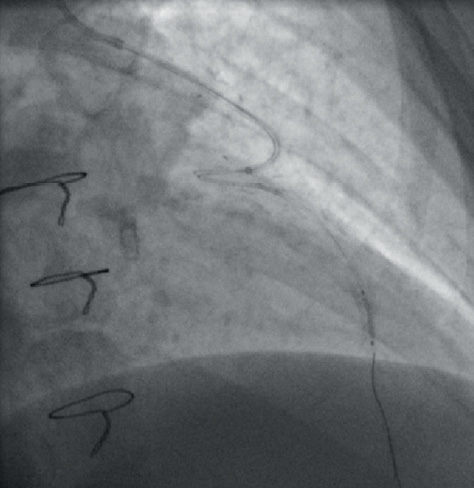

Subsequently a 4 Fr pigtail catheter was passed down the coronary guide and the tail extended to achieve the backward angle required to selectively intubate the LIMA enabling passage of a 0.035” Terumo floppy wire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) deep into the vessel (Figure 5). The pigtail catheter was advanced further into the IMA graft and the guide catheter passed without resistance over the catheter to mid thoracic level (Figure 6). The Terumo wire was exchanged for a 0.014” Runthrough wire (Terumo), which was advanced down the LIMA to the diagonal, then to the LAD and successfully across the critical LAD lesion. The lesion was pre-dilated without difficulty using a 2.5×12 mm Maverick balloon (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) (Figure 7).

Figure 5. A 4 Fr pigtail catheter within a 6 Fr IMA catheter used for deep insertion of Terumo wire into the artery.

Figure 6. Deep seated 6 Fr IMA catheter and Terumo 0.035 inch floppy wire.

Figure 7. Predilation with 2.5×12 Maverick balloon.

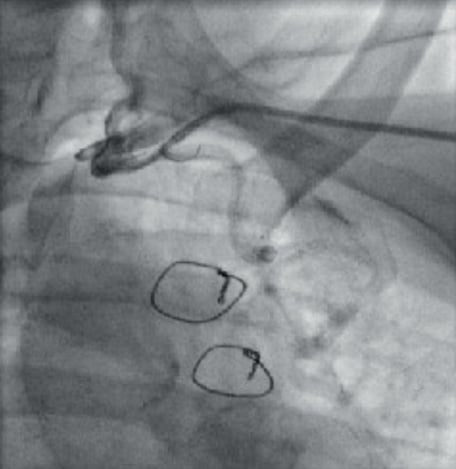

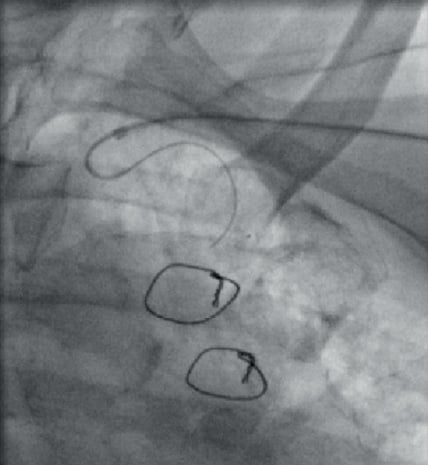

Stent delivery however was challenging. A Promus Element 3×12 mm (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was chosen for deliverability but would not pass one of the many tortuous sections of the LIMA (Figure 8). Introduction of a second Runthrough “buddy” wire for further support did not aid passage of the stent. To achieve better support a GuideLiner catheter (Vascular Solutions, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used and passed far down the LIMA without difficulty, and this enabled successful delivery of the stent to the LAD (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 8. Failed stent delivery due to significant graft tortuosity.

Figure 9. Deep seated GuideLiner to enable stent delivery.

Figure 10. Final result.

Discussion

This case highlights both clinical and technical challenges.

From a technical perspective, there are two important discussion points, firstly the angle for intubating the LIMA graft from the left radial, and secondly, negotiating graft tortuosity successfully.

When the angle into the LIMA is unfavourable and cannot be selectively engaged with conventional guiding catheters, novel use of a 4 Fr pigtail advanced within a standard 6 Fr guiding catheter and the tail unfolded can produce the angles required to enable vessel wiring. This technique offers significant wire back-up support and stabilisation.

The GuideLiner catheter is now a firmly established part of the interventional armamentarium and has been described extensively in the literature.2,3 The GuideLiner catheter is a unique coaxial “mother and child” guide extension allowing deep seating, added back-up support and coaxial alignment. In this particular case deep seating the GuideLiner enabled stent delivery through a particularly tortuous vessel segment, where conventional use of two guidewires failed. It should therefore be considered as an alternative to aid stent delivery through severely tortuous coronary or graft segments.

From a clinic perspective, PCI was selected as the most appropriate way to revascularise this patient despite having significant 3-vessel disease and a failed vein graft, due to high surgical risk and patient preference. Irrespective of a higher mortality and morbidity, redo-bypass surgery is associated with less complete relief of angina and reduced graft patency.4

It was assumed that the trans-radial approach to the LIMA would reduce the risk of a recurrent stroke. The radial approach is associated with a small reduction in stroke risk5 and in the context of vascular tortuosity and a previous cerebrovascular accident complicating femoral angiography, this approach seemed sensible.

Conflict of interest statement

D. Hildick-Smith is on the Advisory Boards and Consultancy for Boston Scientific and Terumo. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Online data supplement

Moving image 1. Tortuous LIMA jump graft from D1 to LAD.

Moving image 2. Critical stenosis in the mid LAD distal to the insertion of the tortuous LIMA jump graft.

Moving image 3. Extreme angle between the left subclavian artery and LIMA take-off.