Case summary

Background: A 60-year-old man with relapsing unstable angina a year after an anterior acute myocardial infarction treated with PCI to proximal left anterior descending (LAD) and proximal intermediate branch (IB), resulting a severely impaired LV function.

Investigation: Physical examination, laboratory test, transthoracic echocardiogram, rest ECG, coronary angiography.

Diagnosis: Severe in-stent restenosis to IB, with a bulky plaque involving distal left main, obtuse marginal and proximal circumflex.

Management: Percutaneous coronary intervention/coronary artery bypass grafting.

Keywords: Left main trifurcation,syntax score, heart team.

How should I treat?

Presentation of the case

A 60-year-old man was referred to our institution with the diagnosis of unstable relapsing angina. Comorbidities included smoking habit, hypertension, mild-to-moderate renal impairment and abdominal aortic aneurysm documented with a recent TC scan showing the presence of parietal thrombus.

In February 2009, he underwent coronary revascularisation with a drug eluting stent implantation to proximal left anterior descending (LAD) and ostial intermediate branch (IB) following a large anterior acute myocardial infarction resulting in a severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. That procedure was complicated by significant gastric bleeding after IIb/IIIa use, resolved by means of urgent endoscopy.

After the first percutaneous intervention he was well on medical therapy.

Since then, medical therapy included aspirin 100 mg/daily, clopidogrel 75 mg/daily, atorvastatin 40 mg/daily, carvedilol 6.25 twice/daily, ACE-inhibitor and gastric protection. When he was referred to us he had good blood pressure control, no major/minor bleeding complications and a substantial feeling of wellness until three days before admission.

At the admission, cardiac enzymes and troponin were normal while the LV ejection fraction confirmed being about 30% with hypokinetic anterior wall.

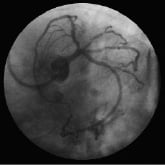

A further coronary angiography was indicated. It showed a bulky plaque involving distal left main (LM), ostial circumflex artery (CX), proximal IB, and an early obtuse marginal (OM) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. “Spider” view showing the bulky plaque involving distal left main, ostial obtuse marginal, ostial Intermediate branch and ostial circumflex artery.

Syntax score has been calculated as 30.

Possible therapeutic options such as further percutaneous interventions, coronary artery bypass or medical therapy even if this had not been deemed suitable were discussed with the cardiac surgeon, the patient and his family.

How could I treat?

We know that distal left main (LM) bifurcation percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) represents “a fake challenge” for interventional cardiology since the majority of randomised trials have shown the benefit of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in this lesions subset1. Therefore, cardiologists should refer these patients to surgery, especially when LM trifurcation is involved.

However, considering that interventional expertise can achieve a satisfactory outcome2-4, the decision to treat a distal LM percutaneously should be undertaken, in our opinion, after careful evaluation of a patient’s clinical history and lesion characteristics.

In the present case, a “surgical approach” could be recommended in view of the angiographic lesion complexity (SYNTAX score 30)5 and the presence of mild chronic kidney failure. Another issue to take into consideration is represented by previous anterior myocardial infarction which resulted in left ventricular dysfunction. Conversely, the relative young patient’s age, the clinical presentation (acute coronary syndrome), the absence of diabetes and the presence of a focal disease might suggest a percutaneous approach.

Despite this early assumption, our clinical decision on this case will be strongly related to assessment of plaque distribution in the distal left main. Indeed, the presence of three/four diseased segments in the context of a distal LM, makes the procedure more difficult and too complex. For these reasons, in our opinion, coronary intravascular ultrasound evaluation should be performed before the treatment. Only if the ostium of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the LM bifurcation carina are found without disease at the IVUS examination, our decision would be PCI with DES, otherwise CABG would be the preferred option.

Percutaneous management

In view of the presence of left ventricular dysfunction, the complexity of procedure and the left coronary artery dominance, a ventricular assistance with intra-aortic balloon pumping is highly recommended before starting the procedure. Considering the importance of the vessels, we think that a 2-stent technique might be advised after predilatation with kissing balloon and wiring of LCX and OM6. Despite the intention-to-treat strategy being a 2-stent technique, appearance of the lesion after kissing balloon is a requisite for making a decision concerning any further strategy.

An 8 Fr left XB guiding catheter is the guiding catheter of choice. Thus, we would perform the wiring of the ramus intermedius (RI), LCx and obtuse marginal (OM), choosing preferably a polymer guidewire as default for LCx and spring guidewires for RI and OM. After that, we would plan a kissing balloon between LCx and MO. If the ostium of OM will suffer after the execution of kissing balloon, a proper dilatation (single or in kissing fashion) should be considered. However, in our experience, the plaque shift phenomenon in the absence of bifurcation carina disease and a large bifurcation area is uncommon7. A V-stenting8 or simultaneous kissing stenting (SKS)9,10 between MO and LCx avoiding to implant a stent on RI, or alternatively a mini-crush (crushing the side as MO and implanting the main branch through the LCX) might be adopted11,12. Following both strategies, rewiring of the RI is strongly suggested in order to dilate the RI through the stents struts. We would conclude the procedure performing a triple kissing balloon between RI, LCX and MO, undersizing the balloon of OM in order to avoid vessel dissection13. However, if the OM will require stent implantation we would consider the internal crush technique or TAP stenting technique as bail-out techniques.

Regarding the antithrombotic therapy, we would administer a bolus of 100 UI/Kg UNF heparin at the beginning of the procedure as we do not plan to use GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors. However, we would give a reload of 600 mg of clopidogrel the day of the procedure and the dual antiplatelet therapy for twelve months after the procedure took place.

How could I treat?

The present case is particularly complex as there are four branches at the distal left main stem (LMS). The patient appears to have a dominant LCx system and should have revascularisation on the grounds of symptomatic and (probably) prognostic benefit. Although there is no specific evidence-base for such a complex patient, we can be guided by risk-assessment. Evaluation of disease anatomy gives an intermediate SYNTAX score of 30. Results of the one-third of patients in the randomised SYNTAX study with an intermediate SYNTAX score, demonstrate a 2-year rate of MACCE of 22.8% for PCI versus 16.4% for CABG, p=0.06, the difference driven by an increased need for repeat revascularisation after PCI.1 Specific results for the LMS subgroup (n=705) demonstrated no significant difference in the composite safety endpoint of death, myocardial infarction or stroke (10.2% for PCI versus 11.8% for CABG, p=0.48). Revascularisation was however higher in the PCI group (17.3% versus 10.4%, p=0.01). This is similar to a large (2,240 patients) non-randomised propensity-score matched study of LMS intervention, where there was no difference in mortality following PCI versus CABG, but revascularisation was higher in PCI-treated patients.2

However, we should also consider clinical factors, particularly the severely impaired left ventricle. The logistic EuroSCORE gives an estimated CABG operative mortality rate of 4.77%;3 similarly, the British Columbia PCI score gives a logistic risk score of 4% for 30-day mortality following PCI.4 Moreover, also relevant to this case, in a recent study of 2,511 CABG patients, those with mild renal dysfunction had a significantly increased operative mortality (5.7% versus 2.5%, p<0.05).5

The stent in the LAD appears good. In the absence of the need to revascularise the anterior wall, I would propose a strategy of PCI. This is significantly less invasive than CABG and associated with a much quicker recovery; the downside being that the patient must appreciate an increased risk of restenosis and potential need for repeat revascularisation.

PCI strategy

In view of the renal dysfunction, consideration should be given to renal protection with saline pre-hydration. With the abdominal aortic aneurysm, a radial approach would be preferred though ideally the case should be performed with an 8 Fr guiding catheter.

The single LAO caudal image provides somewhat limited anatomical information but, in principle, the branches should be protected with guidewires; IVUS is performed to evaluate plaque burden and assess the possible reason for the in-stent restenosis (ISR). Following pre-dilatation, the LCx ostium can be spot stented using a drug-eluting stent (DES). Intervention to the ostium of the OM (with kissing balloon dilatation) would only be undertaken if there was

How did I treat?

Actual treatment and management of the case

The patient firmly refused the surgical approach, therefore a percutaneous revascularisation was scheduled. Dual antiplatelet therapy was already ongoing and abundant hydration along with acetylcysteine administration was immediately started, with ultra-filtration and surgical stand-by.

The presence of the abdominal aortic aneurysm with thrombus apposition contraindicated the use of an intra-aortic balloon pump. With respect to the history of severe gastric bleeding, we decided not to use IIb/IIIa antagonists.

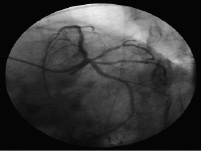

An 8 Fr guiding catheter, three Balance Middleweight™ and a Whisper Extra Support™ wires were used, the latter for the MO (Figure 2a). A first predilation was done to the OM and then a “kissing balloon” predilation to OM and CX (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. A (left side): predilation to obtuse marginal; B (right side): kissing balloon predilation to obtuse marginal and circumflex artery.

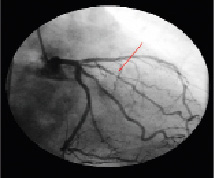

A drug eluting stent was then deployed to the distal LM/proximal CX (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. A (left side): Stent deployment to the distal left main/ostial circumflex artery; B (right side): plaque shift to the ostial Intermediate branch and ostial obtuse marginal.

Thereafter, a significant plaque shift determined the sub-occlusion of the OM and IB (Figure 3b) which resulted in ECG changes along with chest pain and sudden decrease of the blood pressure. “Jailed” wires in the OM an IB were exchanged and a kissing balloon inflation rapidly done to OM and IB in order to restore adequate downstream flow.

This provoked an impaired flow to the CX, probably as a consequence of a distorted geometry of the stent.

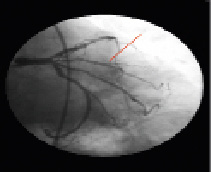

We therefore decided to try passing three balloons. This manoeuvre was feasible through the inner lumen of the 8 Fr catheter (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Simultaneous inflation of three balloons, after wire exchange.

During the balloon inflation, transient gross ECG changes along with significant chest pain occurred again.

The final result was very good, showing a wide patency of the stent in the distal LM/proximal CX, a very good acute gain in the OM and a wide patency of the stent of the IB (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Final result.

At the end of the procedure, 300 ml of contrast had been injected.

Post-procedure

The patient was monitored for two days in the coronary care unit due to a transient further decrease of the LV function which resulted in pulmonary oedema. This was completely resolved on day three after the procedure. The rest of the hospitalisation was event free and he was discharged on day six after procedure.

Three-month angiographic follow-up

Due to the complexity of the treatment and the crucial anatomical site, we proposed to the patient an early angiographic follow-up that he accepted.

At three-month follow-up, patient was asymptomatic, with negative treadmill stress test. Very good angiographic results showed a mild neointimal proliferation to LAD and a moderate stenosis distal to the stent to IB (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Three-month follow up showing a mild neointimal proliferation to LAD and a moderate stenosis to IB distal to the stent.

Mid-term follow-up

After eight months, the patient suffered from a relapse of angina. He presented at the emergency department where cardiac enzymes were negative at the double sampling. No ECG changes were observed. He then underwent stress-echo that documented a reduction of coronary flow reserve to the anterior wall.

A further coronary angiogram was accomplished. The lesion to IB, distal to the stent was seen to have progressed (Figure 7) and thus treated with direct stenting with good final results (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Right caudal view showing the moderate plaque to IB distal to the stent.

Figure 8. Final result of PCI to IB.

The patient was subsequently discharged with a medical treatment of: aspirin 100 mg/daily, clopidogrel 75 mg/daily, atorvastatin 80 mg/daily, carvedilol 6.25 mg twice/daily, ACE inhibitor and gastric protection.

After six months, the patient was asymptomatic and underwent a negative treadmill test.

Discussion

Some considerations need to be taken into account. This report highlights the need of a “heart team” able to discuss together the therapeutic options and deal with the overall management before and after the procedure, which means, in this particular case, the prompt availability of intensive care, surgical back-up and advanced renal function support.

The refusal on the part of the patient for the surgical approach clearly drove the choice of percutaneous revascularisation.

Management of left main disease is still a matter of great debate. The Syntax trial results along with the diffusion of the Syntax Scores from recent major cardiological congresses unfortunately did not resolve the issue of patient selection1,2. Informed patient consent, clinical evaluation and a risk stratification are all co-actors in the “tailored” decision-making process. A Syntax score of 30 did not overcome the patient’s desires.

The complexity of the lesion required a precise planning of the materials which obviously facilitated the procedure. In particular, the use of a 8 Fr catheter, despite being prone to large blood loss, actually allowed the risky manoeuvre of inflating three balloons at the same time. Moreover, the “overall” complexity of the patient required an adequate preparation in order to minimise the inherent risk of the procedure and possible complications.

A comprehensive assessment of the clinical scenario, a collegial critical evaluation of possible strategies along with adequate expertise played a key role in the success of this complex procedure.