Abstract

Aims: The Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting coronary stent has been shown to reduce the restenosis rate compared to bare metal stents and has impacted other clinical measures such as mortality, acute myocardial infarctions (AMI) and target vessel revascularisation (TVR).

Methods and results: Using pooled efficacy data from the Endeavor clinical trial programme, a model was developed to compare the cost effectiveness of the Endeavor drug eluting stent (DES) with the Driver bare meal stent (BMS) over a four year time period. Endeavor was more costly but had an improved clinical outcome compared to Driver BMS over four years with a 4% reduction in deaths, 33% reduction in AMI and a 45% reduction in TVR. Late stent thrombosis was the only event showing an increased incidence for Endeavor of 0.2% compared to 0% for Driver. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio was £3,757/quality adjusted life years (QALY).

Conclusions: Although much controversy has surrounded the appropriate way to assess the cost effectiveness of DES technology, a comprehensive analysis is presented and this suggests that by using extended clinical trial data out to four years, the Endeavor DES in particular, but DES technologies in general, are cost-effective approaches to percutaneous coronary intervention.

Introduction

Bare metal stents represent a significant clinical advance on previous technology such as balloon angioplasty1 and are now the standard of care for coronary intervention but patients can still be at risk of restenosis following stenting, leading to need for a repeat procedure. This is due primarily to neointimal proliferation caused by the vessel wall injury associated with deployment of a BMS2. Drug eluting stents were a major breakthrough in reducing the incidence of restenosis in coronary arteries due to the controlled release of antiproliferative agents designed to limit neointimal hyperplasia3,4.

While the short term advantage has been demonstrated in many clinical trials and meta-analyses5-7, the longer term advantages have been questioned due to the comparative paucity until recently of robust clinical trial data at longer follow-up8,9. More recently clinical data from DES trial programmes extending out to four and five years post-stenting have become available, however true cost-effectiveness is still questioned, with uncertainty compounded by the apparent disagreement on the value of DES between clinicians and economists.

It is the price differential between DES technologies and their BMS predecessors that forms the basis of questions about their cost-effectiveness. Attempts to answer the cost-effectiveness question have led to a wide variety of economic evaluations10-15. In the UK, cost-effectiveness of DES has most recently been evaluated by Bagust et al 200616, who led the group advising The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) during their appraisal of DES technology. Based on the Bagust16 analysis and other models, NICE has issued NHS guidance in 2003 and 2008 limiting the use of DES in the UK to lesions longer than 15 mm and arteries with a 3 mm calibre and has also specified that the price differential between DES and BMS can be no greater than £300. The NICE evaluation highlighted the need for subgroup analysis to determine the outcomes of those at particularly high risk of restenosis (generally recognised as those with longer lesions or smaller vessel diameters) but has excluded diabetic patients as a relevant subgroup population to be considered in the final recommendation. This is against the clinical evidence demonstrating an increased risk for restenosis in diabetic patients17.

The economic model presented here attempts to provide an alternative economic evaluation of DES in the UK setting enhanced by a more complete clinical trial dataset, whilst relying as far as possible on the assumptions of the models used in the assessment of DES by NICE. It uses the ENDEAVOR DES as the basis for evaluation.

Methods

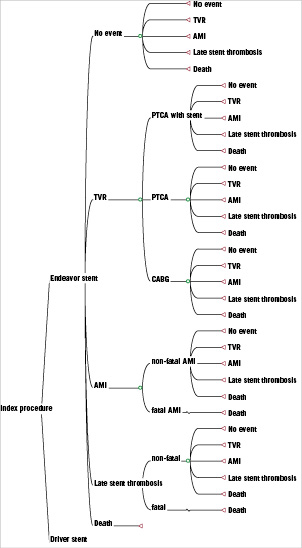

A cost effectiveness analysis of Endeavor DES compared to Driver BMS was undertaken using a Markov model by allowing patients to transition between health states in order to accrue costs and benefits (quality adjusted life years). This was performed from the perspective of the National Health Service (NHS) with costs and benefits discounted at the NHS standard yearly rate of 3.5%18 to reflect the time preference of receiving a health benefit sooner rather than later. The model predicts occurrence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) including death, AMI, TVR and late stent thrombosis over a four year time horizon. If a TVR were needed, treatment options were considered to be percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) with stenting, PTCA without stenting and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). For any further stenting required, it was assumed that patients would receive the same stent type as initially with no crossover between DES and BMS. A model decision tree is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decision tree of the Endeavor DES Markov model.

Clinical data

The efficacy and safety of Endeavor DES has been evaluated through an extensive clinical trial programme including Endeavor I19,20 (ClinicalTrials.gov trial ID NCT00248079), Endeavor II22 (NCT00614848), Endeavor II Continued Access (CA)23, Endeavor III24 (NCT00217256), Endeavor IV (NCT00217269) and Endeavor V25 (NCT00623441). There were small variations in the inclusion criteria for patients with single de novo native coronary artery lesions for each of these trials. Endeavor I included patients with reference vessel diameter between 3.0–3.5 mm and lesion length <15 mm19. Endeavor II, Endeavor II CA, Endeavor III included patients with reference vessel diameter between 2.25–3.5 mm and lesion length: 14–27 mm22,23, Endeavor IV included patients with reference vessel diameter between 2.5-3.5 mm and lesion length <27 mm26, and finally Endeavor V enrolled all patients presenting with coronary artery lesions suitable for stent implantation25.

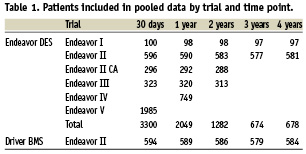

Pooled clinical data for a follow-up duration out to four years from the trials included in the Endeavor clinical trial programme were utilised in the economic model including mortality, AMI, TVR and late stent thrombosis. Of these trials, only the Endeavor II trial has directly compared the clinical and radiographic efficacy of Endeavor DES with Driver BMS and it was from this trial that clinical data on the efficacy and safety of Driver BMS were derived. A summary of the sample size of patient data available at different time points from each of the trials contributing to the pooled data is found in Table 1. Pooled trial data were used in the basecase which considers it through a four year time-point.

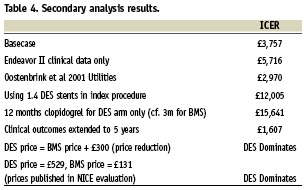

Secondary analysis was performed to test the impact of alternative input variables in the model. The efficacy for year five was predicted for BMS using Benestent I trial data27, and for Endeavor DES in year five it was conservatively assumed that it has no advantage over BMS in year five. For late stent thrombosis, it was assumed that the advantage of BMS over DES would continue according to a meta-analysis of DES stents28. In other secondary analyses, alternative inputs that were explored including considering clinical trial data exclusively from the Endeavor II trial as opposed to pooled data, using alternative utility values29, using an average of 1.4 DES stents in the index procedure instead of 1.12 DES stents as suggested by an observational registry of Taxus6,30, and alternative DES and BMS pricing scenarios using NICE recommended prices47.

Cost and utility data

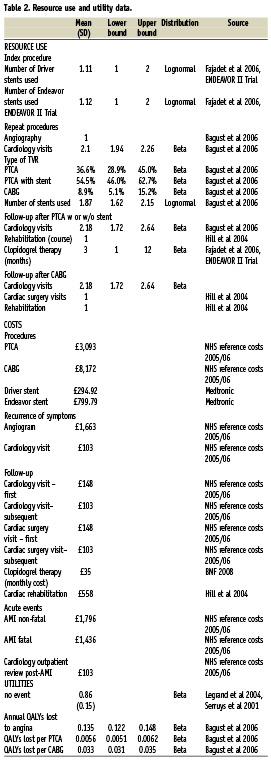

Utility data for the basecase were derived in line with a recent UK cost effectiveness study of DES stenting in a UK setting by Bagust and colleagues16. Although the Bagust publication has been criticised31, these data were chosen because they were an essential element of the UK study that to date has been the most critical of the cost effectiveness of DES. A baseline utility of coronary artery disease requiring stenting of 0.86 was calculated based on ARTS (arterial revascularisation therapies studies)32,33. Alternative utility data presented by Oosterbrink et al 200129 were also tested in the secondary analysis.

A base year of 2007 was used for the costing. Costs of procedures, repeat procedures, follow-up, cardiac events and cerebrovascular events were extracted from publicly available sources and inflated to 2007 costs when necessary. For purposes of validation and comparability, model inputs were aligned with those from Bagust et al 200616 wherever possible. A summary of model input data can be found in Table 2.

Model analyses

The cost effectiveness model was designed to calculate expected cost effectiveness as as well as allowing for a probabilistic analysis in order to consider variability in the input data. For the probabilistic analysis, a beta distribution was applied to MACE event occurrences and mortality but no variance in costs was tested in line with the Bagust model. The model did not consider any specific subpopulations but considered all patients who were eligible for enrolment in the clinical trial programme. A one way deterministic sensitivity analysis was performed by varying key variables by ±20%. The relative influence of each variable on the incremental net benefit of Endeavor versus Driver was represented with a tornado diagram.

Results

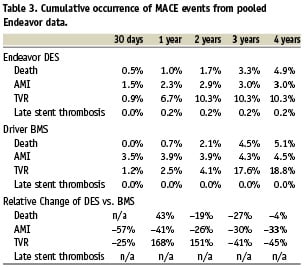

Pooled clinical data of occurrences of selected MACE events at time points 30 days, one year, two years and three years from the Endeavor clinical trial programme (Endeavor I, Endeavor II, Endeavor II CA, Endeavor III, Endeavor IV and Endeavor V) are presented in Table 37,20,25,26.

Based upon pooled data over a four year time horizon the number of patients needed to be treated with Endeavor instead of Driver in order to prevent MACE events would be 500 patients to avoid one death, 67 patients to avoid one AMI and 12 patients to avoid one TVR.

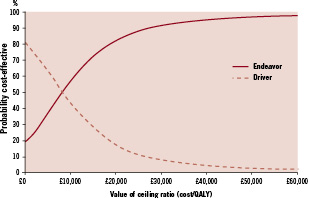

In the basecase over a four year period, the total cost of care with Endeavor was £5,739±£191 and the total cost of care with Driver was £5,636±£128. The total QALYs gained for these two arms were 3.11±0.66 and 3.08±0.57 respectively. Therefore the incremental cost effectiveness ratio of Endeavor versus Driver was £3,757/QALY gained. This was found to be 62% likely to be cost effective at a threshold of £20,000/QALY and 81% likely to be cost effective at a threshold of £30,000/QALY (Figure 2) (£20,000 to 30,000 being the range beyond which interventions are unlikely to be considered cost-effective by NICE37).

Figure 2. Cost effectiveness acceptability curve.

Besides the basecase assumptions, several other scenarios were tested in secondary analyses and the resulting ICERs are presented in Table 4.

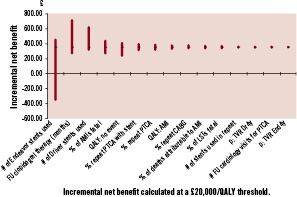

One way sensitivity analysis was performed indicating the most sensitive variables in the model in order of influence were the number of Endeavor stents used, the length of clopidogrel therapy after stenting, number of Driver stents used and the percent of AMIs that were fatal, and the baseline utility score (Figure 3). However, Endeavor’s ICER increases above £20,000/QALY gained –a threshold currently accepted as the maximum society is willing to pay for health benefits in the absence of other special considerations – only if the average number of Endeavor stents used in the index procedure increase to above 1.85.

Figure 3. Tornado diagram – sensitivity analysis. Incremental net benefit calculated at a £20,000/QALY threshold.

Discussion

Drug eluting stents have demonstrated consistently superior clinical efficacy over bare metal stents6,38. However, DES comes at a price premium compared to BMS. This model has demonstrated that Endeavor stent is cost effective for all patients included in the clinical trial programme compared to a cost effectiveness threshold of £20,000/QALY with a basecase incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £3,757/QALY using conservative estimates for both efficacy and utilities. Although this is lower than ICERs that have been reported previously, this is reflective of a longer period of trial data that has confirmed that the benefits of DES extend at least as far as four years and comes from an understanding and use of true costs involved. Endeavor is likely to be even more effective in certain patients than others as has been found in other subpopulation evaluations such as in diabetics, those patients with smaller vessel diameter and in patients with a longer lesion length16,39-44. Subgroup analyses were not undertaken here due to insufficient powering (especially at longer follow-up) and because the objective of this model was to confirm Endeavor’s (and likely other DES) cost effectiveness in a general population instead of limited high risk populations uniquely. It must also be considered that this model includes only single vessel disease and will not accurately represent the cost effectiveness in patients with multiple diseased vessels.

Although both TLR and TVR are commonly used metrics of restenosis, in this analysis TVR was selected as the key outcome over TLR. Since TLR only considers restenosis within the lesion itself whereas TVR considers the entire vessel where the stent is located, TVR was considered to be a more stringent measure of efficacy. This was also considered to be more clinically relevant than the unconventional outcome used by Bagust et al 200616 where all revascularisations were considered to be relevant to the presence of the stent, regardless of proximity of the stenosis to the stent.

Occurrence of late stent thrombosis in DES patients has been identified as being either equal to or more common than late stent thrombosis in BMS patients, which has been hypothesised as being related to stent design45. Pooled analysis of clinical trials of CYPHER and SIRIUS have indicated that compared to BMS, stent thrombosis is at a similar level through the first year. However, after that first year, occurrence of late stent thrombosis is more common for DES than BMS (SIRIUS 0.6% versus BMS 0.0% p=0.03; CYPHER 0.7% versus BMS 0.2% p=0.03)28. Data for Endeavor on late stent thrombosis used in this model through year four indicates that late stent thrombosis was also more common in Endeavor than in BMS (Endeavor 0.1% versus BMS 0.0% p=0.11) without reaching statistical significance. Late stent thrombosis is a relatively uncommon occurrence, therefore it is possible that there is insufficient statistical power to detect differences in this population28 and some of the difference in late stent thrombosis rates in DES patients can be explained by baseline characteristics46.

This model demonstrated better cost effectiveness for Endeavor DES compared to other DES models. Other DES modelling in a UK setting has identified a cost per QALY of £29,587 for Taxus® (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) stents and a cost per QALY for Cypher® (Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA) ranging from £9,702 (diabetic patients) to £29,259 (no risk factors present)6. Given the similar efficacy and costs of Endeavor, Taxus and Cypher stents6,7,28, it might be expected that they would have similar cost-effectiveness results. However, these other cost effectiveness analyses were based upon two years or less of trial data. In contrast, this model incorporates four years of efficacy data for Endeavor. This provides an opportunity to replace previous conservative assumptions about DES efficacy beyond the then-limited trial data for important clinical factors such as TVR.

Data used in this model are largely based upon efficacy derived from clinical trials performed under tightly controlled conditions. Both BMS and DES efficacy are measured in this context, so it is still possible to make a meaningful comparison between the two even if the full efficacy might not be achievable in general clinical practice. In a recent registry, the late stent thrombosis rate for DES patients at three years was 1.3% compared to 0.2% observed in the ENDEAVOR trial programme although this analysis was not specific to Endeavor DES and did not have a relevant BMS control arm46. Sufficient long term patient registry data must be collected for DES and BMS before differences in effectiveness can be fully tested.

There are several limitations to the analysis. These include the reliance on the Endeavor clinical trial programme to inform many different resource use variables including stent use. Secondly, several parameters (including type of TVR performed) were used from the original modelling performed by Bagust et al 200616 despite the fact that their model was heavily criticised. These parameters were chosen to reflect conservative assumptions regarding DES and to minimise the changes in data from previous analyses. This enables us to highlight the link between improvements in cost effectiveness and the use of new efficacy data out to four years.

Conclusion

The evaluation presented here demonstrates that even under conservative assumptions, over a four year time frame Endeavor is likely to be cost effective for patients in whom stenting is appropriate. This is further evidence that drug eluting stents appear to be a cost effective way of treating symptomatic angina.