Introduction

Histology and intracoronary imaging identified different types of calcified nodules (CN), such as eruptive and non-eruptive CN, each characterised by different underlying pathophysiology, which in turn can result in distinct histological and morphological features. To date, there is still no consensus on whether these characteristics can influence the applicability, effectiveness and long-term outcomes of calcium modification strategies and percutaneous coronary intervention.

Pros

Giulio Guagliumi, MD; Dario Pellegrini, MD

For years, calcified nodules (CN) have not been taken seriously by interventional cardiologists. They were just considered an unusual rocky form of culprit lesion, rarely observed by pathologists in sudden cardiac death. With the progressive increase of calcified coronary arteries due to patients’ ages and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes and chronic kidney disease) and the detection by intracoronary imaging of CN as a cause of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in one-third of severe calcified lesions, curiosity was transformed into a need to improve the outcomes of such complex interventions1.

Pathology and intracoronary imaging identify a CN as an eccentric, protruding calcified mass with fragments disrupting the fibrous cap, surrounded by thrombi. Cap disruption differentiates CN from nodular calcifications (NC) and, thus, provides an alternative definition of eruptive versus protruding nodules. However, both entities share common structures and origins2. In highly calcified coronary arteries, protruding nodules are frequently sandwiched between proximal and distal calcified plates (usually concentric). When tortuous right coronary arteries or other regions with hinge-like movements (ostia or bifurcations) are involved, the repetitive torsion may break the nodule, releasing calcium fragments and causing localised thrombosis, typical of CN. Thus, any NC may present as a CN, if granted enough mechanical stress and time. Based on this, it seems reasonable to consider all nodules equal for clinical management, while also taking into account that even optical coherence tomography, despite its great accuracy, may struggle to differentiate thrombi from calcified spikes, resulting in significant diagnostic overlap. Treatment strategy should rely on two main elements: clinical presentation and haemodynamic significance of the stenosis. The frequent detection of nodules in stable settings implies that the absolute risk of events is low. So, in the case of ACS presentation, antithrombotic therapy, and revascularisation only if needed (based on the imaging of the lumen area), may be a feasible strategy.

In the case of revascularisation, nodules present significant challenges. First, they are associated with suboptimal procedural results, as they reduce the minimum stent area (although a sufficient area is usually achievable); there is a higher incidence of strut malapposition (especially at the nodule shoulders due to the inherent limits of the metal alloy in adapting to this extreme geometry), stent eccentricity and underexpansion3. Optimal results may not be achievable despite aggressive post-dilation, which may only increase the risk of complications. In addition, the operator should account for severe calcifications in the proximal and distal segments and severe tortuosity which may prevent device delivery. Finally, the combination of tortuosity and nodule and hinge motion may increase the risk of stent fracture and target lesion failure.

Lesion preparation is mandatory. Balloon dilation works mainly through eccentric expansion of the healthy vessel wall opposite the nodule but with a higher risk of dissection and perforation and only marginal effects on the nodule itself. Rotational or orbital atherectomy may be attempted in order to tackle superficial calcifications, but the difficult interaction between the device and the nodule portends variable results4. Intravascular imaging provides detailed information for vessel sizing, the evaluation of the nodule and surrounding calcifications, and the assessment of lesion preparation. Careful imaging-guided burr escalation or an increase in crown speed may improve results and limit procedural risks. Intravascular lithotripsy is effective in eccentric calcifications and can also address surrounding heavy calcifications, so it is now often the first option for operators5. Still, more data are needed.

In conclusion, operators dealing with nodules should promptly identify the risks and challenges of these complex interventions, including the setting of calcified, tortuous vessels and elderly, comorbid patients. Imaging guidance may improve procedural outcomes and support the operator, especially in treatment optimisation and, if needed, in the difficult decision of refraining from additional treatment escalation, in case of an unfavourable benefit-to-risk ratio.

Conflict of interest statement

G. Guagliumi reports receiving grants from Infraredx and consulting fees from Abbott. D. Pellegrini has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Cons

Gary S. Mintz, MD; Akiko Maehara, MD

Histopathology studies2 show that an eruptive calcified nodule is characterised by multiple nodular fragments of calcification penetrating and disrupting the overlying fibrous cap and protruding into the luminal space with evidence of endothelial cell loss and an occlusive or non-occlusive platelet/fibrin thrombus. An eruptive CN appears to be initiated through fragmentation of necrotic core calcifications and is the third most common cause of an acute coronary syndrome. Conversely, non-eruptive nodular calcium (NC) is composed of areas of nodular calcification of varying sizes, often accompanied by fibrin with a thick, intact fibrous cap; it occurs within the plaque, is related to the extent of the underlying calcification, does not involve disruption of the fibrous cap and, therefore, does not involve contact with the lumen.

Using standard resolution intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), it is difficult to identify thrombus or an intact versus a ruptured fibrous cap. Thus, it is likely that published articles employing standard resolution IVUS used the term calcified nodule indiscriminately to include eruptive CN, non-eruptive NC, or both. At most, the clinical scenario of patients included in some of these articles may be used to infer the underlying morphology particularly if a study is limited to ACS patients. For example, in a study by Sugane et al6 that included only ACS patients, an eruptive CN was associated with high rates of major adverse cardiac events (57%) and ACS recurrence (37%) during the observational period (median=1,304 days).

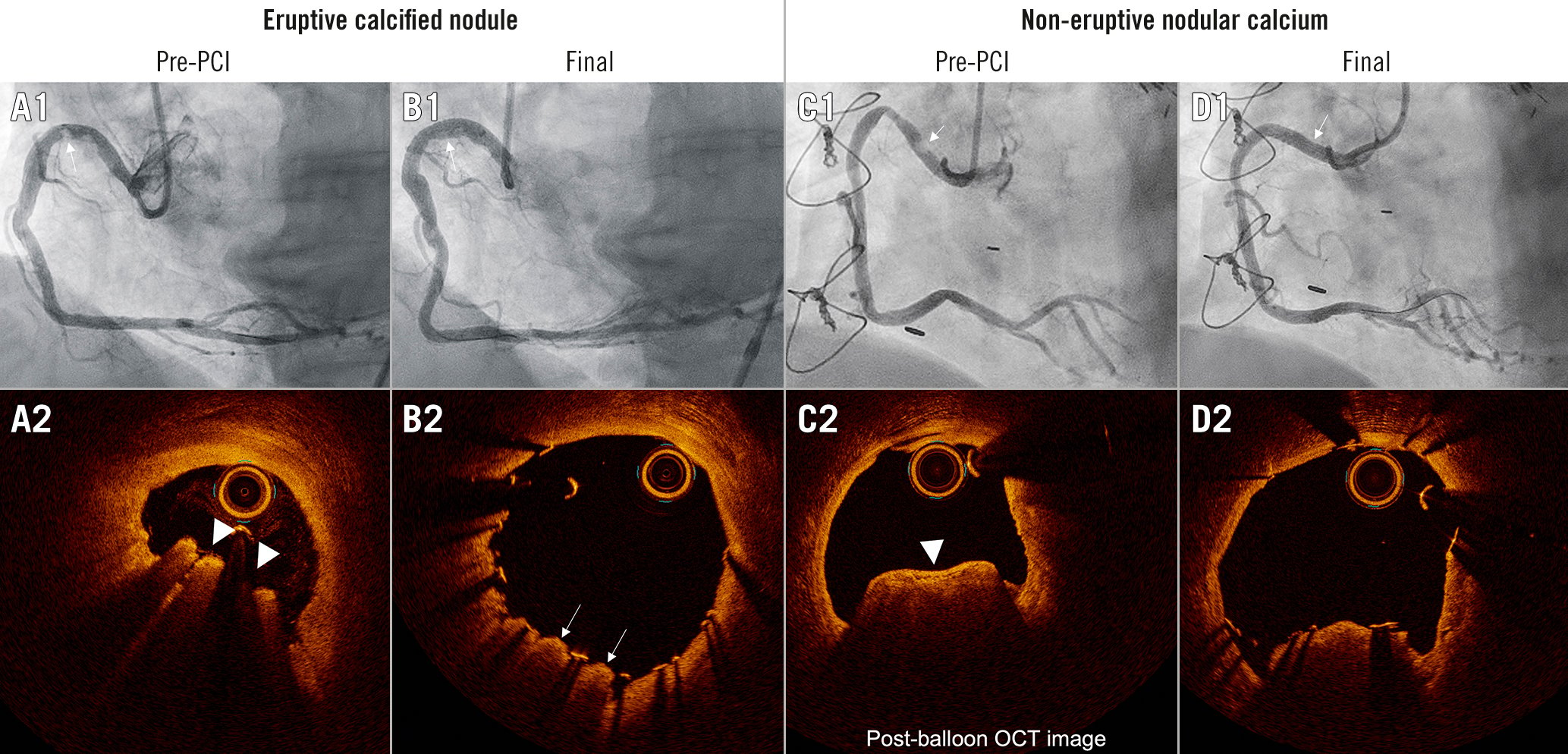

Unlike standard resolution IVUS (and there are currently no studies using high-definition IVUS), optical coherence tomography (OCT) can differentiate an eruptive CN from non-eruptive NC (Figure 1). In a secondary analysis from the CLIMA natural history registry and based on OCT findings, Prati et al reported that the composite incidence of cardiac death and/or target lesion myocardial infarction occurred in 20% of unstented patients with an eruptive CN versus 2.7% with non-eruptive NC (p<0.001)7. We recently used OCT to compare patients with an eruptive CN versus non-eruptive NC who were treated with stenting. Stent implantation was associated with the deformation of an eruptive CN but not of non-eruptive NC (Figure 1); although stent expansion was greater, the protrusion of small calcium fragments was more frequent and target lesion revascularisation was twice as common in lesions with eruptive CNs versus non-eruptive NC (18.3% vs 9.6%; p=0.04)4. (Sato T, et al. Impact of eruptive versus non-eruptive calcified nodule morphology on acute and long-term outcomes after stenting. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. In press.) Eruptive CN are also more likely to cause problems with equipment delivery and even stent dislodgement due to the intraluminal calcified spicules that are not seen with non-eruptive NC. Finally, stent implantation into an eruptive CN has been associated with a high prevalence of recurrence of the eruptive CN within the stent, especially in the first year post-stenting, although the exact mechanism (acute intrusion at the time of stent implantation, late intrusion, stent fracture, or continued growth) has yet to be elucidated67.

Eruptive CN and non-eruptive NC have distinct and different histopathological and OCT imaging morphologies27, long-term outcomes when treated medically7, and acute and long-term responses to percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation68 (idem Sato et al). The only thing they have in common is that they can both be difficult to manage. Despite anecdotal case descriptions, there are currently no data regarding the use of calcium modification (yes/no) or the best calcium modification device prior to stent implantation when treating either an eruptive CN or non-eruptive NC.

Figure 1. Representative cases of eruptive CN and non-eruptive NC. A1-D1) Coronary angiograms. A2-D2) The OCT images corresponding to the white arrows in A1-D1. Eruptive CN is an accumulation of small calcium fragments, protruding and disrupting the overlaying fibrous cap typically with small amounts of thrombus (white triangles in A2). Non-eruptive NC is an accumulation of small calcium fragments with a smooth intact fibrous cap without overlaying thrombus (white triangle in C2). Usually, eruptive NC will be deformed by stenting, archiving a round-shaped stent with an optimal minimum stent area. Sometimes protrusion of parts of the eruptive CN can be observed (white arrows in B2). On the other hand, non-eruptive NC (C2) will not be deformed by stenting, resulting in an oval-shaped smaller stent area achieved by stretching the non-calcified circumference (D2). Notice that the angiographic appearance was identical in the two cases. CN: calcified nodule; NC: nodular calcifications; OCT: optical coherence tomography

Conflict of interest statement

G. Mintz is a consultant for and receives honoraria from Boston Scientific and Gentuity. A. Maehara is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Philips, and Shockwave Medical.