Abstract

Aims: To conduct a risk-adjusted gender-based analysis of clinical outcomes following drug-eluting stent (DES) versus bare metal stent (BMS) implantation in patients with coronary artery disease.

Methods and results: We compared risk-adjusted total mortality rate, myocardial infarction, and event-free survival (defined as freedom from death, myocardial infarction and/or repeat revascularisation) in a consecutive cohort of 7,662 patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention at our institution, including 1,835 (25.4%) women. Follow-up was six months to 6.2 years (mean: 3.5 years; median: 3.6 years). The women were older than men and more likely to suffer from diabetes, hypertension or congestive heart failure. Smokers were more often men, and men were more likely to have had prior coronary bypass surgery compared to women. A DES was used in 39.9% of males and 39.5% of females. Both genders derived a significant long-term clinical benefit from DES compared to BMS; advantages were observed for mortality (men: HR=0.78, 95% CI: 0.64-0.96, p=0.016; women: HR=0.62, 95% CI: 0.45-0.85, p=0.003) and major adverse cardiac events (men: HR=0.73, 95% CI: 0.63-0.84, p<0.001; women: HR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.52-0.84, p=0.001). Among BMS-treated patients, women had worse cumulative clinical outcomes than men. DES eliminated the gender differences in cardiac prognosis.

Conclusions: Our analysis indicated a profound prognostic advantage for DES versus BMS among both genders, though female patients appeared to derive the greatest benefit.

Introduction

Gender influences atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) risk1, and may conceivably affect the efficacy of coronary revascularisation procedures2. Drug-eluting stents (DES) have become important revascularisation tools. DES have been shown to decrease the frequency of restenosis in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in randomised clinical trials and large patient cohorts3. Accordingly, interest in the possible impact of gender on clinical outcomes following contemporary catheter-based interventions has been increasing4,5.

The field of “gender medicine” looks at the fundamental differences between men and women with regard to physiology and pathophysiology, particularly in response to therapeutic interventions6. The impact of DES on clinical and angiographic outcomes in women is of particular interest because CAD is a major determinant of morbidity and mortality among both genders, but particularly among elderly women7.

Over the last few years, we have managed a comprehensive database including all patients undergoing PCI at our medical centre. We recently published a risk-adjusted analysis of all PCI cases using “match-propensity score” analysis, showing that the DES improves long-term clinical outcomes among an “all comers” group of coronary patients treated at our institution8. In the current study, we aimed to explore the gender-specific and risk-adjusted clinical impact of DES use in female versus male patients with severe CAD.

Methods

Study population and data sources

The study population comprised all consecutive patients (n=7,662) undergoing PCI with stent implantation between 1 April 2004 and 31 December 2009 at our institution. Patients were distinguished by gender and two cohorts were generated for the current analysis. Atotal of 1,835 (25.4%) women and 5,827 (74.6%) men underwent PCI at the two hospitals of the Rabin Medical Center (Beilinson and Hasharon Medical Campuses). Overall, DES were utilised in 39.8% of patients (Cypher [Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA] 51.1%, TAXUS® [Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA] 12.7%, Endeavor® Sprint [Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA] 17.1%, XIENCE V/Promus [Abbott Vascular, Redwood City, CA, US] 13.6%, Resolute® [Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA] 3.0%, BioMatrix®/Nobori® [Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan] 2.5%). Early after the introduction of DES to the public health system in Israel, guidelines and reimbursement rules were formulated by the Israel Heart Society and the Ministry of Health. DES were to be used preferentially in proximal main vessels, diabetic patients, long lesions, in stent restenosis lesions and chronic total blocks. The logic for this choice was the greater expected benefit of reducing restenosis in these patients and also greater salvage of myocardium at jeopardy in case of restenosis.

Follow-up was six months to 6.2 years (mean: 3.5 years; median: 3.6 years). Outcome endpoints during follow-up included death, myocardial infarction (Q and non-Q wave), need for coronary bypass surgery (CABG), catheter-based target vessel revascularisation (TVR), and hierarchical composites of death or myocardial infarction (MI), TVR, or CABG (total major adverse cardiac events, MACE).

Data collection was approved by the hospital ethics committee in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with a waiver for the need for individual informed consent. All patients were initially prescribed lifelong aspirin and clopidogrel for at least three months after BMS implantation and three to 12 months following DES implantation.

Since 2007, all patients with a DES have been prescribed clopidogrel for at least one year following implantation, and treated with PCI following an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) event regardless of the type of stent implanted. All data regarding the index, subsequent procedures, and clinical and echocardiographic data were extracted and processed from the patients’ electronic medical record system. Demographic data and death dates were obtained from the medical centres’ demographic information system, which is linked to the Israel Ministry of the Interior data system and the General Sick Fund (health organisation) data warehouse. The accuracy of the mortality data was verified with the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. All data regarding prior and subsequent hospitalisations, including all ICD-9 diagnoses, were retrieved from the medical centres’ data warehouse. Laboratory data were retrieved from the medical centres’ central laboratory database. Definitions regarding ST-elevation MI (STEMI) were obtained from the Rabin Medical Center interventional cardiology database, which records detailed data regarding all STEMI patients.

Definitions

All patients with at least one DES implanted in the index PCI were included in the DES groups according to gender. A total of 4,750 (62% of the cohort) patients had echocardiographic data prior to the PCI date. All patients with moderate or worse left ventricular dysfunction defined in the echo record were flagged as “moderate to severe left ventricular dysfunction”. All patients who arrived at the PCI laboratory after resuscitation or with cardiogenic shock were flagged as “critical state”. PCIs for acute/recent MI or ACS were defined according to the indication as noted on the electronic record. Primary PCI for STEMI was defined by the prerequisites for inclusion in the STEMI registry: within 12 hours of symptoms, without prior thrombolysis. The number of vessels with coronary disease was determined by analysing the diagnostic catheterisation report. Significant disease was considered when >50% stenosis was noted. Treated territories were defined by analysing the angioplasty report. For each territory, PCI sites were counted (e.g., proximal left anterior descending [LAD] and mid-LAD, diagonal branch 1st or 2nd) and a simple score of sites/territories, termed “complexity”, was defined, which reflects the number of discrete lesions treated per territory. Whenever treatment involved at least one ostial or proximal main vessel (LAD, circumflex [CX], or right coronary artery [RCA]) or left main (LM), the procedure was flagged as “proximal main vessel”. Total stent length and “stent length/lesion” were calculated and filed for each procedure. Repeat hospitalisation was categorised as MI, ACS, or CABG according to the main relevant ICD-9 diagnosis. TVR was defined as a subsequent PCI to the same vessel as the index PCI.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.10 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All tests were two-tailed, and p<0.05 was considered significant. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed by the main author.

Cohort analysis

Baseline parameters were compared among genders and between groups distinguished by the type of stent using the Students t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. A propensity score was calculated for the female and male cohorts using a multivariable logistic regression model with receipt of a DES or BMS as the independent variable and all pre-PCI and intra-procedural variables as covariates. We included all clinically meaningful variables (e.g., age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, prior heart failure, smoking, prior creatinine, prior haemoglobin, prior platelet count, prior use of anticoagulants, prior CABG, known moderate to severe left ventricular [LV] dysfunction, prior dementia, prior malignancy [except superficial skin malignancy], PCI for STEMI, PCI for MI or ACS, severe state, the number of vessels with coronary disease, territories treated, complexity score, treatment of proximal main vessel, and total stent length) without pre-analysis to choose relevant variables. Cases were then sub-classified by quintiles of the propensity score, both for checking the balancing effect of the score and for the initial outcome analysis of the entire cohort. The balancing effect on the variables used for the propensity score was checked by logistic or linear regression (according to the variable) with each variable as the dependent variable and stent type and dummy coded strata variables as covariates. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier procedure with stratified analysis of the log-rank statistic according to the quintiles of the propensity score.

Propensity score matching and subgroup analysis

Propensity score matching was performed separately for the male cohort and the female cohort using a “closest neighbour” algorithm attempting to match each DES patient with the BMS patient with the closest propensity score and a maximal difference of less than 0.25 times the standard deviation of the scores. Each pair was used once, and unpaired cases were not used in further analysis. The baseline characteristics were re-analysed as in the main cohort. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier procedure. Amultivariate Cox regression analysis was performed with stent type, propensity score, and any unbalanced variables as covariates9-11.

We also performed a gender-based analysis of the propensity matched outcomes distinguished by the clinical presentation (i.e., stable presentation, ACS, STEMI), stent type and according to age cut-off (≥/<65 years old).

Multivariate analysis

A Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed to determine the independent predictors of all-cause mortality and MACE. Variables were selected using a forward stepwise algorithm with entry and stay significance levels of 0.1. The multivariate analysis was designed to separate the independent effect of gender on outcome (death, MACE) from other co-variables (e.g., age, diabetes, congestive heart failure, acute MI, number of vessels treated, etc.).

Results

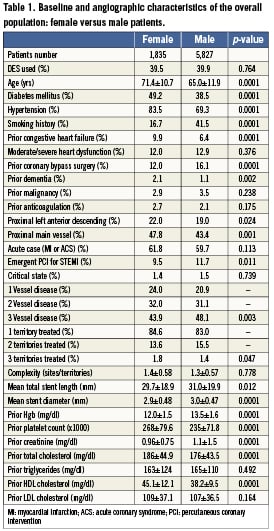

Women were more likely to be older, suffer from diabetes mellitus or hypertension, and to have sustained prior congestive heart failure compared to men (Table1). Smokers were more often male, and men were more likely to have sustained prior coronary bypass surgery compared to women. Men were treated more often for STEMI compared to women. However, the rate of PCI for acute coronary syndrome (including STEMI, non-STEMI, and unstable angina together) was similar for both women and men. Women were treated more often for proximal main vessel disease, but men were more likely to sustain three-vessel CAD (Table1). Mean stent diameter was 0.1 mm greater for men compared to women. The proportion of DES use was ~40% for both genders. Laboratory test differences between genders are summarised in Table1.

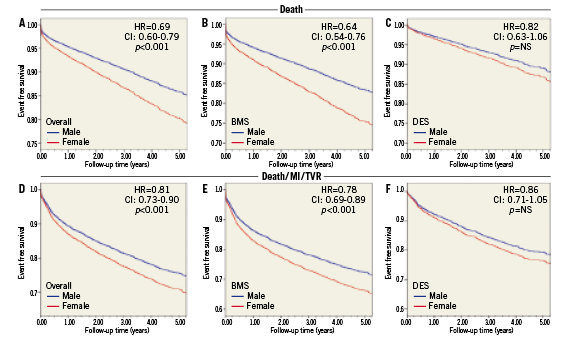

In the unmatched group of patients (n=7,662; 25.4% female) distinguished by gender and sub-categorised according to stent type, the mortality rate was greater among women compared to men during late follow-up (Figure1A). However, a different survival pattern emerged when the study group was divided according to stent type. Though mortality was significantly greater over time in BMS-treated women compared to BMS-treated men (Figure1B), similar survival curves were found for the DES-treated groups when comparing genders (Figure1C). A similar event-free survival pattern was noted in female patients for composite MACE (death/MI/TVR) in the overall population and BMS-treated patients compared to men (Figures1D and 1E). However, MACE was similar between DES-treated men and women (Figure 1F).

Figure 1. Unadjusted mortality-free (A-C) and MACE-free (D-F) curves. (A) and (D): overall women vs. men; (B) and (E): bare metal stent (BMS) group; (C) and (F): drug-eluting stent (DES) group

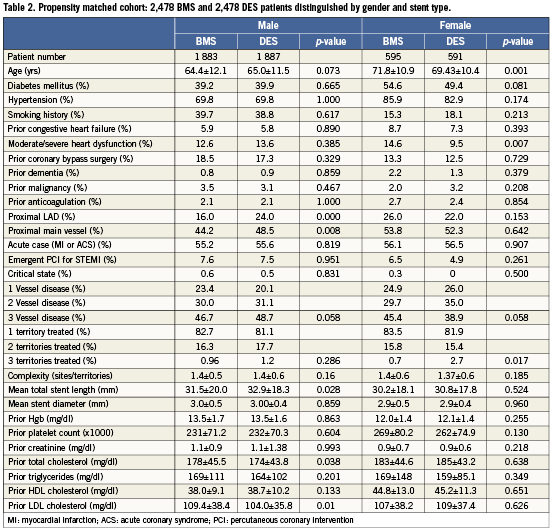

The propensity-matched cohort yielded a group of 1,883 BMS-treated versus 1,887 DES-treated males and 595 BMS-treated versus 591 DES-treated female patients. Due to the propensity matching process explained above, no major differences were noted in the vast majority of baseline, angiographic, anatomic, and laboratory characteristics between male and female patients who received DES compared to those who received BMS (Table2). Despite propensity matching, male patients were more often treated with a DES in the proximal LAD or any proximal main vessel. Female patients treated with BMS were somewhat older than men. Females were treated with a DES slightly more often than a BMS for three territories. Despite propensity score matching, LDL cholesterol levels were higher among BMS-treated males than DES-treated males, but this was not found to be the case among women.

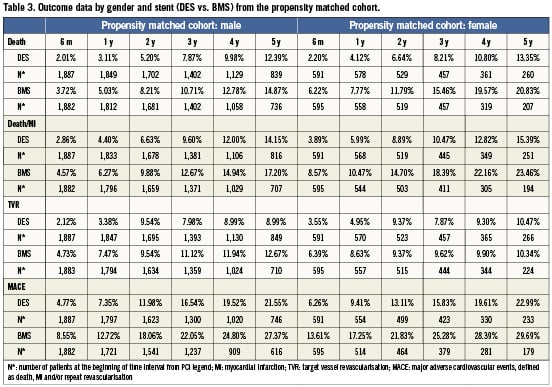

The outcome parameters of the propensity-matched cohort are presented in Table3 according to gender. Most of the endpoint parameters, including mortality, MI, the composite of MI/death, and overall MACE, occurred at higher rates in the BMS-treated women compared to the other groups. Patients treated using DES sustained less TVR compared to treatment with BMS, but no significant difference in the rate of TVR was found between women and men.

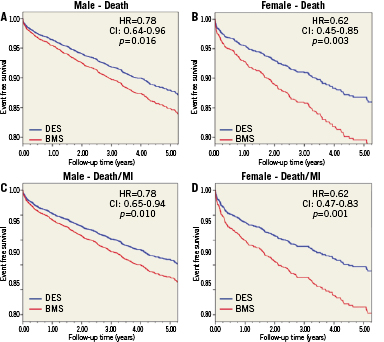

Propensity score–adjusted cumulative incidence curves for all-cause mortality according to gender and the type of stent used are presented in Figures2A and 2B. A mortality advantage was noted for both men and women treated with DES compared to BMS (men: HR=0.78, 95% CI: 0.64-0.96, p=0.016; women: HR=0.62, 95% CI: 0.45-0.85, p=0.003). The continued divergence of the curves indicates a persistent benefit of DES over BMS over time. The beneficial effect of DES seemed to be more profound among women, whereas the worst survival outcome was observed among BMS-treated women compared to the other groups. By examining the death or MI rates, the benefit of DES compared to BMS was also significant for both genders, but it seemed to be more profound among women (Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 2. Comparative outcomes of DES and BMS-treated patients from the propensity score model. (A): mortality among men; (B): mortality among women; (C): death/MI among men; (D): death/MI among women

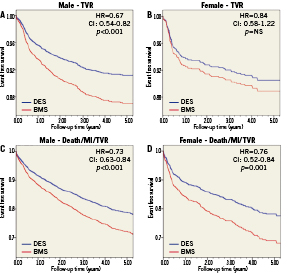

When the rates of clinically-driven TVR were evaluated (Figures 3A and 3B), an advantage of DES over BMS was noted in men (H =0.67, 95% CI: 0.54-0.82, p<0.001), and it was not significant among women (HR=0.84, 95% CI: 0.58-1.22, p>0.05). As depicted in Figure 3A, a clear benefit of DES was noted in the first 12 months after implantation with a persistent trend over time. An advantage of DES treatment was also noted in both genders when MACE was examined (men: HR=0.73, 95% CI: 0.63-0.84, p<0.001; women: HR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.52-0.84, p=0.001; Figures 3A and 3D).

Figure 3. Comparative outcomes of DES and BMS-treated patients from the propensity score model. (A): TVR among men; (B): TVR among women; (C): death/MI/TVR among men; (D): death/MI/TVR among women

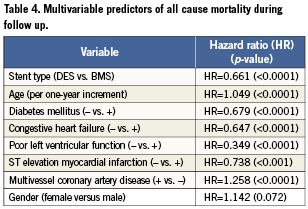

In a multivariate analysis of all patients treated by PCI at our institution, gender did not emerge as a significant independent predictor for mortality or MACE during the follow-up period. The HR for mortality (women versus men) was 1.142 (95% CI: 0.99-1.32, p=0.072) and 1.06 for MACE (95% CI: 0.95-1.17, p=0.279). Independent predictors of mortality during follow-up among our treated patients are listed in Table4. The variables that were predictive of mortality were stent type (DES versus BMS), age increment, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, poor LV function, STEMI, and multi-vessel CAD.

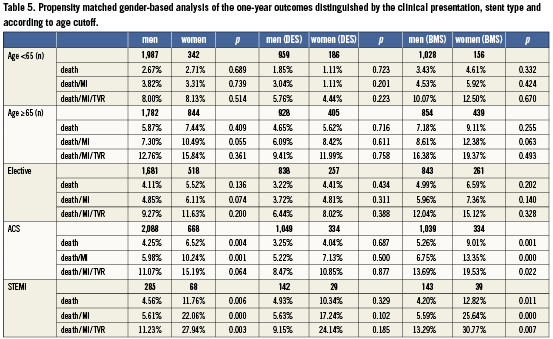

The one-year outcome of the subgroup analysis is shown in Table5. It indicates a remarkable prognostic difference in favour of men primarily in the acute (i.e., ACS/STEMI) cases and especially among BMS-treated patients. However, the gender difference was remarkably attenuated in DES-treated patients and the number of STEMI patients was too small to indicate meaningful differences. No significant age-related interaction was found between the subgroups.

Discussion

Our risk-adjusted long-term outcome analysis indicated a prognostic advantage of using DES for both genders. In addition, female patients appear to derive as many clinical benefits, or even a greater medical advantage, from treatment with DES. In fact, women who received a BMS had the worst prognosis in our PCI cohort, whereas the benefit of DES among females attenuated the observed gender difference in cardiac prognosis. The study confirms that women referred for PCI in general are older and have a higher risk profile resulting in higher rates of adverse clinical events. Thus, our results may indicate the potential need for closer follow-up of women focusing on gender-specific issues and risk-factor management.

Both groups experienced less TVR following DES implantation, but the difference was significant only for men. This difference may have been due to sample size differences, and it may indicate that areduction in TVR is not the sole determinant of the clinical benefits of using DES in ischaemic patients, particularly women, treated with stents. It should also be acknowledged that we were able to track only clinically-driven TVR that might have been less in women, not because of less restenosis but rather because of fewer referrals for repeat catheterisations. Regardless, the overall MACE was improved in both groups with the use of DES compared to BMS.

The present analysis is an extension of our prior investigation ascertaining the long-term safety, efficacy, and pattern of DES use in our routine clinical practice8. We previously reported on 6,583 consecutive patients who underwent PCI at our institution, 2,633 of whom were treated using DES and 3,950 with BMS. Over a mean follow-up period of three years and after propensity score matching, the cumulative mortality was 12.85% in the DES group and 14.14% in the BMS group (p=0.001). In our previous analysis, the use of DES compared to BMS reduced the occurrence of MI, clinically-driven TVR and the MACE composite endpoint of death/MI/TVR (23.38% vs. 26.07%; p<0.001). Thus, the current analysis expands upon our previous observation, and it focuses on gender-related issues in the characterisation, management, and prognostication of women treated by contemporary PCI for symptomatic CAD compared to men.

Our analysis is one of the largest single-centre registries comparing DES and BMS implantation, with the longest period of follow-up. The results also emphasise that, even in the current PCI era, the outcome is poorer for female patients than men. Although the difference was not sustainable in our multivariate analysis model, it does not refute the odds that gender-related differences still exist for cardiac prognosis. However, our results highlight the advantage of DES implantation among both female and male patients by reducing the most crucial clinical endpoints, including death and the composite of death/MI, in addition to previously published advantages, such as reduced TVR and MACE. The benefits of reduced mortality and MI with DES were even more apparent among women, whereas the decline in TVR was more intense among men.

Earlier studies have suggested that women sustain increased mortality following PCI compared to men, which may be explained by differences in comorbid clinical conditions2. The morphology of CAD was found to be similar among women and men, though women have smaller vessels on average12. The gender differences in clinical and angiographic outcomes following PCI seem to be more profound in acute coronary syndromes, particularly following MI events5,6. It is of interest that in our analysis, DES attenuated the prognostic advantage of men versus women primarily among ACS patients treated using PCI. The explanation for this phenomenon remains to be determined.

In the modern PCI era, several studies have explored the impact of gender on clinical and angiographic outcomes following various type of DES implantation13-18. In general, women were older and more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, renal insufficiency, congestive heart failure and smaller coronary vessels. The relative extent of reduced angiographic and clinical restenosis with DES compared to BMS was similar for men and women resulting in asignificant reduction in the one, two or three-year rate of MACE driven by a lower incidence of TVR/TLR rates in both genders. Female gender was not an independent predictor of binary restenosis or clinical outcomes in multivariate analysis, regardless of stent type. However, late loss data were not identical among women or men for the various type of DES examined13-18.

Strengths and limitations

The present study was our experience at a single centre (two hospitals). However, it is a large primary and tertiary centre with homogeneous policy, practice, and treatment standards. We chose an “all-comer” cohort of female and male patients reflecting our “real-world” experiences. Nonetheless, our study is not a randomised or prospective clinical trial, and the allocation of DES or BMS was according to the operator’s clinical judgement. Our analysis did not indicate gender bias in treatment selection because the proportion of DES use was similar between genders. However, unmeasured confounders may still have theoretically influenced the selection of stents in our study, which could impact patient outcomes. We approached this potential bias by utilising a propensity-matching scheme that balanced all known confounders in both gender groups. Data regarding long-term pharmacological medical treatment is not provided. Although we could not obtain data regarding the duration of clopidogrel use following PCI, we can assume that patients with DES used clopidogrel for long periods due to our homogenous treatment policy. This applies to all coronary patients regardless of their sex. In addition, data on the use of oral contraceptives is lacking in our analysis. This might have been an important determinant of the risk of restenosis in young women. Finally, our study was self-funded, without any industry involvement.

Conclusions

Using an unselected PCI population, our gender-specific and stent-based risk-adjusted analysis indicates a profound prognostic advantage for DES compared to BMS in both genders. Female patients appeared to derive an even greater benefit from DES treatment. BMS-treated women experienced the worst prognosis among our PCI cohort. Thus, our data encourage that the use of DES be maximised among both women and men in order to attenuate the potential difference in cardiac prognosis between genders.

Funding

No grants or financial support were used for this study, or any relations with industry.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.