Abstract

Aims: To determine whether there are gender-based differences in in-hospital outcomes among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods and results: We studied a large cohort using clinical data from a registry of 130,985 PCI procedures in Belgium, from January 2006 to February 2011. Compared to males, females were significantly older (70.3 vs. 64.8 years), and were more frequently diabetic or hypertensive. Men smoked more and more frequently had previous myocardial infarction (MI), previous PCI or previous coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. Coronary artery disease (CAD) was less severe in women, and PCI to the left anterior descending artery was more common in female patients. Unadjusted in-hospital mortality rates were higher in females versus males (2.5% for women and 1.6% for men, p<0.0001). After multivariable analysis, female gender remained an independent predictor of mortality (odds ratio 1.35, 95% CI: 1.22-1.49, p<0.0001).

Conclusions: Gender-based differences in hospital mortality rates after PCI were observed in this large registry. Female sex remained an independent predictor of mortality after multivariable adjustment.

Introduction

Despite significant advances in the management of coronary artery disease (CAD), this pathology is still one of the major causes of death worldwide today1. Cardiovascular disease is the first cause of death in women in Europe. According to the European Heart Network, cardiovascular disease accounts for 42% of deaths in women under 75 years of age2. Even though the prevalence of CAD is greater in men than in women at any given age, several reports have shown that female gender is associated with worse outcomes in case of ischaemic heart disease3,4. Gender-related differences in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis5, in cardiovascular risk factors6, in clinical presentation7 and in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease8 are well known. Recently, analyses from the PROSPECT study showed that there were gender-specific differences in the extent and composition of coronary plaques in patients <65 years of age, suggesting that atherosclerosis development and progression were influenced by gender9,10. Differences according to sex have also been outlined in the management and outcomes after acute coronary syndromes11. Concerning outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the question is still debated and controversial. In earlier studies, female gender was identified as an independent predictor of adverse outcome after PCI12. In contrast, more recent studies have demonstrated that female gender had no or minimal impact on outcomes after adjustment for clinical and anatomical variables13,14.

The aim of this study was to analyse gender differences in in-hospital outcomes in patients who underwent PCI in Belgium from January 2006 to February 2011.

Methods

PATIENT POPULATION

The Belgian Working Group on Interventional Cardiology registry is a prospective procedure-based database. A web-based standardised case record form (CARDS database, European Heart House, Nice, France) is completed for each procedure, allowing collection of detailed data in all patients undergoing PCI in the 36 Belgian hospitals performing PCI. Data collection includes clinical, demographic, procedural and angiographic characteristics as well as in-hospital outcomes.

We analysed data from January 2006 to February 2011. During this period, 131,119 procedures were performed. Of these, 134 procedures were excluded from the analysis due to missing gender data.

ENDPOINTS AND STUDY DEFINITIONS

The primary outcome for this study was all-cause in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints included the need for coronary artery bypass grafting, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), major bleeding, major vascular complication, renal failure requiring dialysis, post-procedural myocardial infarction and acute stent thrombosis. A composite secondary endpoint only including major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) was also analysed. Standard definitions were used to define the most common clinical scenarios.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD. Differences were deemed significant if p<0.05. We used the chi-square test and Student’s t-test to compare groups, as appropriate. Regression analysis was performed using univariable then multivariable logistic regression modelling in order to identify the independent predictors of death and secondary endpoints. Multivariable models were formed by including significant univariable predictors for the outcome variable of interest. Variables with a value of p<0.10 in univariate analysis were incorporated into the model in a forward stepwise manner. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

BASELINE, ANGIOGRAPHIC AND INTERVENTION CHARACTERISTICS

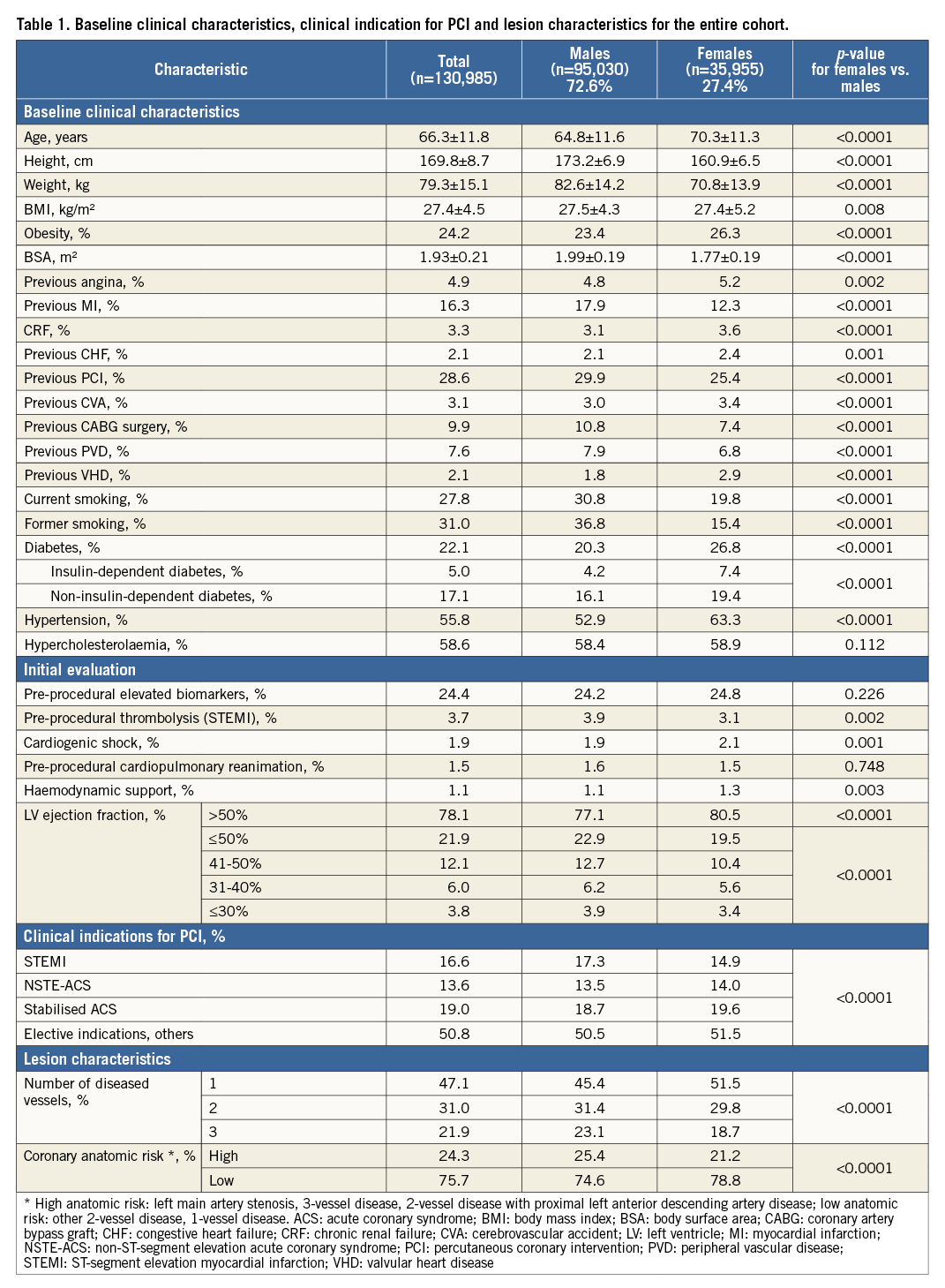

Among the 130,985 PCI performed, 35,955 were performed in women. Compared with men, women were significantly older and were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal failure (CRF), prior stroke, previous valvular heart disease (VHD) or previous congestive heart failure. Conversely, history of prior MI, prior PCI, prior CABG surgery or prior peripheral vascular disease (PVD) were less frequent in women than in men. Women were also less likely to be smokers. Of note, the proportion of patients with hypercholesterolaemia was similar in both groups (Table 1).

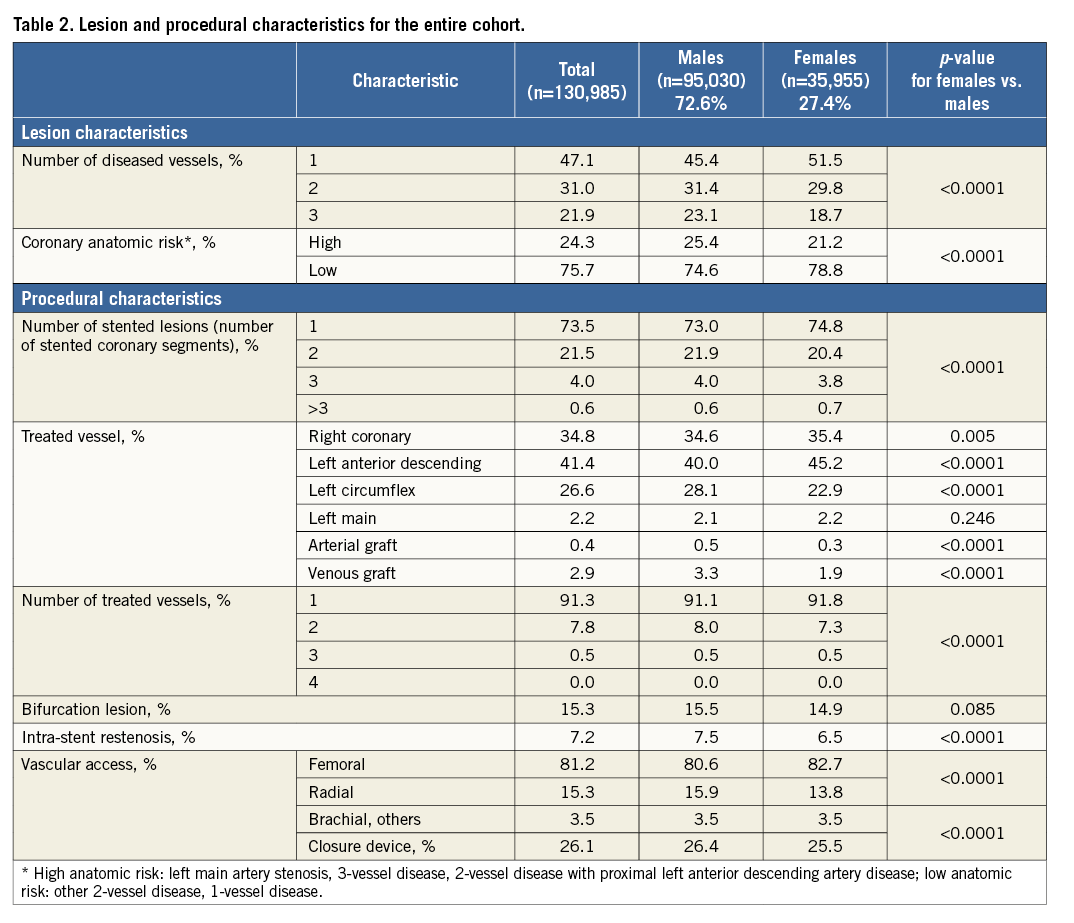

Regarding PCI indication, most cases were elective procedures in both groups but men were more likely to present with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Cardiogenic shock and inotropic support at presentation were more frequent in women. Reduced left ventricle function was more common in male patients. A significant gender-based difference was observed in the severity of CAD, with more frequent single-vessel disease in women and more high-risk coronary artery disease (defined as left main artery stenosis, 3-vessel disease, 2-vessel disease with proximal left anterior descending artery disease) in men. The lesions more often involved the left anterior descending coronary artery in women and more frequently the left circumflex artery and grafts in men. The procedural data showed a slightly greater number of treated vessels and treated lesions per patient in men (Table 2).

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

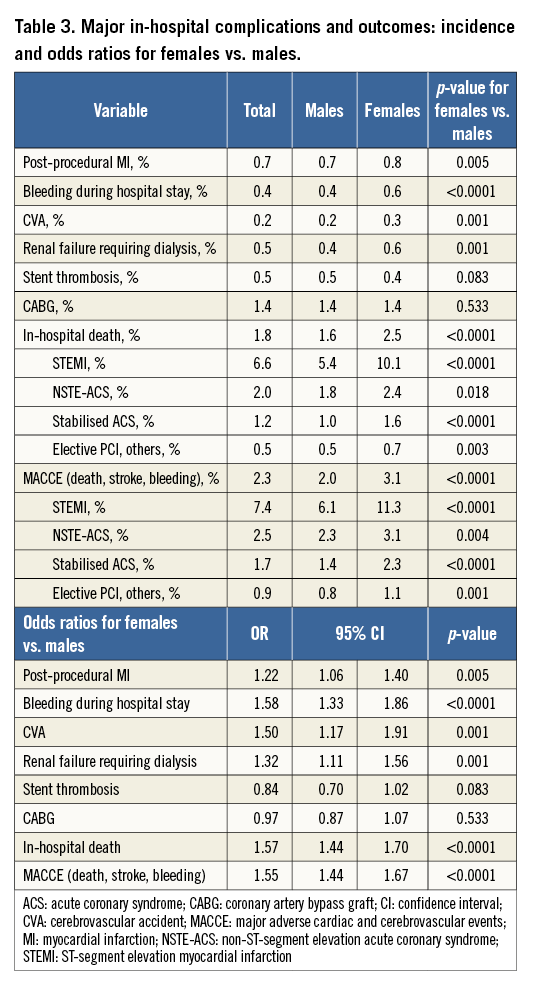

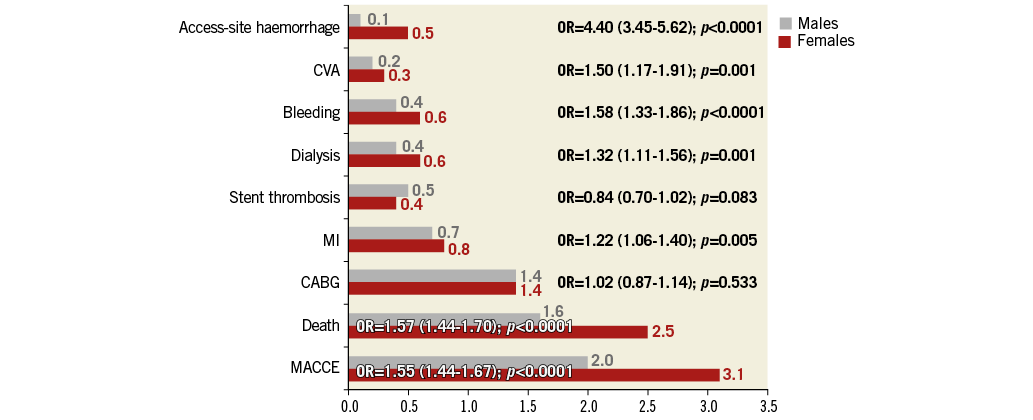

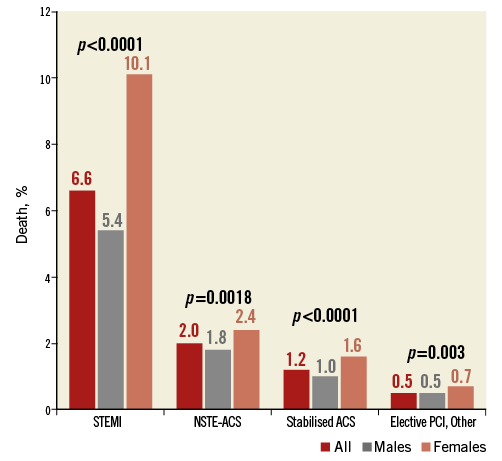

In-hospital death rate was 1.8% (n=2,297), and women had a significantly higher risk of death: 2.5% vs. 1.6% in men (p<0.0001), odds ratio (OR) 1.57, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.44-1.70, p<0.0001 (Table 3, Figure 1). Women had a higher risk of in-hospital death after PCI in all clinical settings (i.e., acute coronary syndrome [ACS] and stable angina), but the difference in death rate was particularly high in case of acute coronary syndrome, especially in case of STEMI. There was a graded relationship between mortality rates and clinical indication for PCI: elective PCI (0.7% vs. 0.5%, p=0.003), to NSTE-ACS (2.4% vs. 1.8%, p=0.018), to STEMI (10.1% vs. 5.4%, p<0.0001). In each clinical subgroup, a significant gender-related difference was seen, with the worst prognosis in women (p<0.0001) (Figure 2). Women were more likely to have a MACCE (death, stroke or severe bleeding) during hospital stay, with a rate of 3.1% in women and 2.0% in men (OR 1.55, 95% CI: 1.44-1.67, p<0.0001). The rate of severe bleeding was higher in female patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1. In-hospital complication rates after PCI for females vs. males and odds ratios for in-hospital complications for females vs. males. CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction

Figure 2. In-hospital mortality rate according to gender and indication for PCI. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

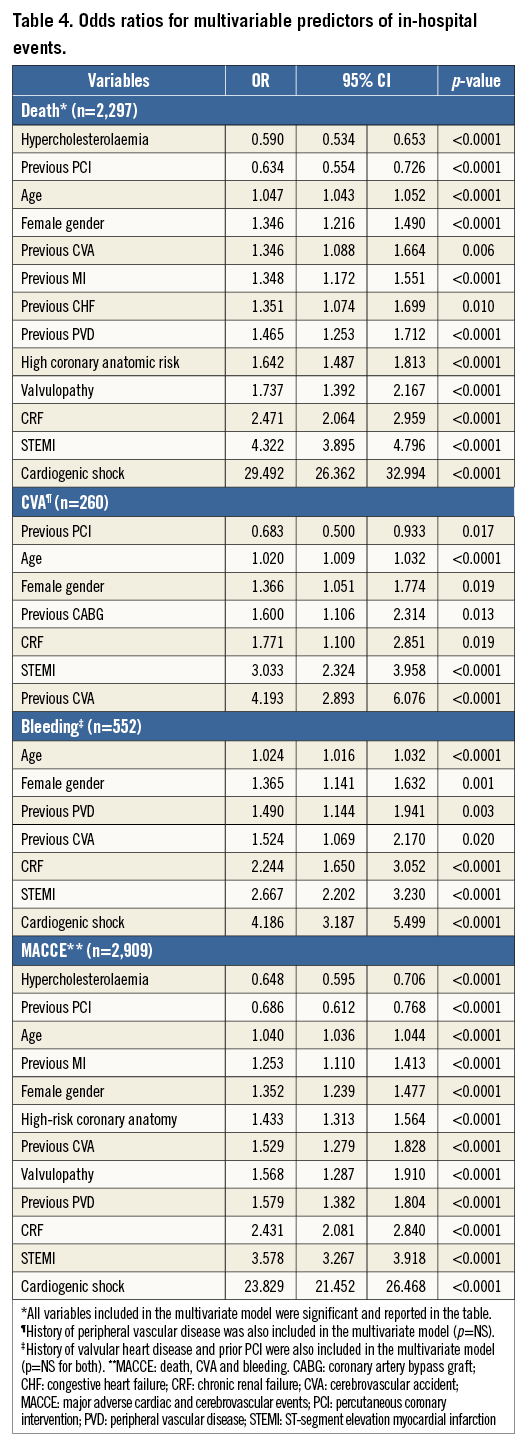

After univariate analysis of clinical, angiographic and procedural analyses, we identified independent risk factors for death in multivariate analysis (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, female gender was a significant independent risk factor for in-hospital death (OR 1.35, 95% CI: 1.22-1.49, p<0.0001). The other independent risk factors were age, prior MI (OR 1.35, 95% CI: 1.12-1.56, p<0.0001), hypercholesterolaemia, prior PCI, prior PVD, prior VHD, CRF, high coronary anatomic risk, STEMI and cardiogenic shock. In multivariate analysis, female gender was an independent risk factor for bleeding (OR 1.37, 95% CI: 1.14-1.63, p=0.001), stroke (OR 1.37, 95% CI: 1.05-1.77, p=0.019) and MACCE (OR 1.35, 95% CI: 1.24-1.48, p<0.0001) (Table 4).

Discussion

From the Belgian PCI registry, the main results of this study are marked gender-based differences in in-hospital mortality rates following PCI. Even after robust multivariable adjustment, female gender remained an independent predictor of mortality, bleeding, stroke and MACCE.

We observed significant differences between men and women in terms of clinical characteristics, angiographic characteristics, interventions and in-hospital outcomes. Baseline characteristics in our study showed that women were older at the time of PCI. It is known that women develop cardiovascular disease seven to ten years later than men, a difference thought to result, at least in part, from the protective role of endogenous oestrogen15. As hypertension and diabetes prevalence increases with age, the higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in our female cohort is partly in relation to the older age of female patients undergoing PCI. On the other hand, the higher prevalence of CAD in men16 is consistent with the higher rate of prior MI and PCI observed in this subset of patients. In the literature, the rate of severe CAD and multivessel disease is lower in the female population compared to males17,18. This was confirmed in our study: the OR for a high-risk coronary anatomy was 0.79 for women (95% CI: 0.77-0.81, p<0.0001) and coronary multivessel disease was less frequent in female patients. This apparent dissociation between a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and lower angiographic severity of ischaemic heart disease in women has been previously described19. However, the mechanism involved and the reasons explaining such discrepancy remain unclear. In cohort studies, gender bias could be responsible for decreased access to PCI for women with advanced CAD11. The mode of presentation of CAD, which varies according to gender, could also explain this observation: women more frequently have angina pectoris as first symptom whereas men present more frequently with MI, influencing the access to coronary angiography20. This difference in the proportions of acute and elective indications for PCI between male and female patients is confirmed in the present cohort.

There is controversy about mortality and adverse event rates between men and women undergoing PCI. Early studies analysing gender differences in clinical outcomes showed that interventions in women were associated with higher rates of complications and higher rates of intervention failure21. It has been argued that these results were secondary to unadjusted analyses, clinical characteristics and comorbidities being responsible for the observed differences. Currently, it remains clear that in unadjusted analysis women have poorer outcomes than men following PCI. To identify the role of gender on outcomes, several studies with adjusted analyses for clinical characteristics (i.e., robust multivariate analysis or propensity score analysis) have been reported recently with varying results. Some studies show a persistent gender-related difference in outcomes after adjustment12,22, while others show that sex is not an independent factor of outcomes13,23. The most recent large studies performed in the DES era do not show gender-specific differences in mortality following PCI after adjustments14,24. Conversely, female gender was an independent correlate of long-term mortality in the PCI arm of the SYNTAX trial, despite adjustments for risk factors25,26. In our study, there is a significant difference in in-hospital mortality between men and women after PCI. Even after multivariate analysis and multiple adjustment for confounding factors, female gender remains an independent predictor of in-hospital death and MACCE.

Mortality rate after PCI varies according to PCI indication, as observed in the European registry Euro Heart Survey of PCI27. Significant sex-related difference in mortality is observed in each clinical subgroup, particularly in patients presenting with STEMI. A worse prognosis in women admitted for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) contributes to the difference in mortality rates between women and men.

The difference in mortality rate between genders can be explained partly by older age and more frequent comorbidities in the female cohort. Nevertheless, in our study, female gender is an independent predictor of death after multivariate analysis with an increase in risk of death of 35%. Complications, such as severe bleeding, acute renal failure or stroke are more frequent in female patients, particularly in patients presenting with ACS. These complications may be considered as a factor contributing to the increased mortality rate in females undergoing PCI.

The influence of female gender on outcomes might be explained by differences in coronary physiology, anatomy and in cardiovascular risk factors. As some of these factors may be under-evaluated or unknown, female gender may appear as an independent predictor of adverse outcome even though it may be associated with other causative factors (hormonal status, endothelial dysfunction, micro-circulation disorders, etc.)5.

There is a lack of consistency across studies concerning the influence of gender on clinical outcome after PCI. Many earlier studies relied on relatively small samples, were single-centre studies, focused on different populations or did not analyse the same factors. Additionally, thanks to better PCI techniques and medical management, adverse event rates have decreased in high-risk populations, including women. Nowadays, it is statistically more difficult to show significant event rate difference among groups, and large population analyses are needed28.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, as a multicentre registry, it offers observational data on selected patients undergoing PCI. Thus, it is limited to patients who have had PCI and does not account for the outcomes of women who undergo cardiac catheterisation without intervention and women who are referred for CABG. Second, even though multivariate analysis was performed, we cannot exclude the influence of confounding factors in our results. Finally, SYNTAX scores were not registered and are lacking in the analysis. SYNTAX scores would probably be more sensitive to determine the influence of lesion severity on the outcomes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate a significant difference in in-hospital mortality rates between men and women undergoing PCI. This difference is particularly marked in patients undergoing PCI for ACS. After robust adjustment for known predictors of mortality, female gender remained an independent predictor of death, being associated with a 35% increase in risk of death as compared to male gender. However, there is a lack of consistency in findings across studies evaluating gender difference in outcomes after PCI. Larger studies in populations treated with current PCI techniques and cardiovascular medical treatment are needed to identify factors explaining these differences in outcomes.

| Impact on daily practice Female gender is associated with worse outcomes in case of ischaemic heart disease and after PCI, particularly in patients undergoing PCI for ACS. After adjustment for clinical and anatomical variables, results vary between studies and the influence of gender as an independent risk factor for outcomes after PCI is still under debate. In daily practice, gender differences in terms of presentation of CAD and outcomes after PCI have to be considered. |

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.