Abstract

Unprotected left main (LM) bifurcation coronary lesions are challenging for interventionists because these lesions are associated with relatively poor outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Although the single-stent technique is a default treatment strategy for LM bifurcation lesions, elective double stenting is still used in patients with severely diseased side branches. The crush technique and its variants, the culotte technique and the simultaneous kissing stent technique, are applicable for distal LM disease, but none of these has proven to be superior to the others. Good long-term clinical outcomes are closely related to procedural success and optimisation of the stenting technique. The use of kissing balloon inflation during any double-stent technique is known to be an independent predictor of good angiographic and clinical outcomes by avoiding incomplete apposition or expansion. Moreover, procedural guidance using intravascular ultrasound may improve outcomes by helping to determine the appropriate stenting technique and optimise the stent procedure. Therefore, more attention should be paid to optimising the chosen technique than to choosing among techniques.

Introduction

Previous studies have reported comparable efficacy and safety between percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for unprotected left main (LM) coronary artery disease1,2. Based on those results, PCI is currently recommended by the 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines3. Nonetheless, PCI for distal LM lesions remains associated with relatively poor clinical outcomes4,5. Moreover, a debate exists on the best stenting technique, despite the double-stent technique being more frequently used for LM bifurcation than for non-LM lesions, due to concerns regarding the ischaemic volume applied to the myocardium6. In this review, we discuss the appropriate context for the use of the double-stent technique and how outcomes can improve after PCI for LM bifurcation lesions.

Indications for the double-stent technique

In spite of several randomised trials on bifurcation coronary lesions, there is still a lack of randomised studies comparing elective double and provisional stent techniques used for distal left main bifurcation lesions. Based on non-randomised studies6 and on extrapolations from non-LM bifurcation randomised studies7, the single-stent technique is considered the default strategy for bifurcation LM lesions. However, despite the current consensus on the single-stent technique, side branch (SB) occlusion after main branch (MB) stenting can lead to circulatory collapse and is a serious potential complication in LM bifurcation interventions. In a recent bifurcation stenting registry enrolling 2,227 cases of bifurcation PCIs treated by the one-stent approach, the incidence of SB occlusion was 13.4% for true and 4.0% for non-true bifurcation lesions8. Hence, the elective double-stent technique remains a viable option for LM bifurcation lesions.

The decision to pursue a specific strategy for individual LM bifurcation lesions should involve clinical and angiographic factors. Double stenting can be performed in patients with non-urgent clinical presentation and complex angiographic morphologies. Angiographic morphologies of the distal LM, which should be carefully evaluated, include the plaque distribution, the bifurcation angle, and the size and jeopardised area of the left circumflex artery (LCX)6,9. When the plaque is distributed along all segments of the LM, left anterior descending artery (LAD), and LCX, PCI for distal LM lesions is associated with a greater risk of repeat revascularisation9. Therefore, LM bifurcations having an LCX of ≥2.5 mm in size and ≥50% stenosis on angiography are potential candidates for double stenting10. In particular, when the LCX ostium has difficult access with diffuse stenosis, double stenting is often considered. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) examination allows more accurate evaluation of disease extent and stenosis for both MB and SB. An IVUS study showed that the majority of cases of LM disease had significant plaque at the ostial LCX even in lesions with mild or intermediate angiographic stenosis11. Nonetheless, some surgeons still adopt the single-stent technique regardless of LCX severity12.

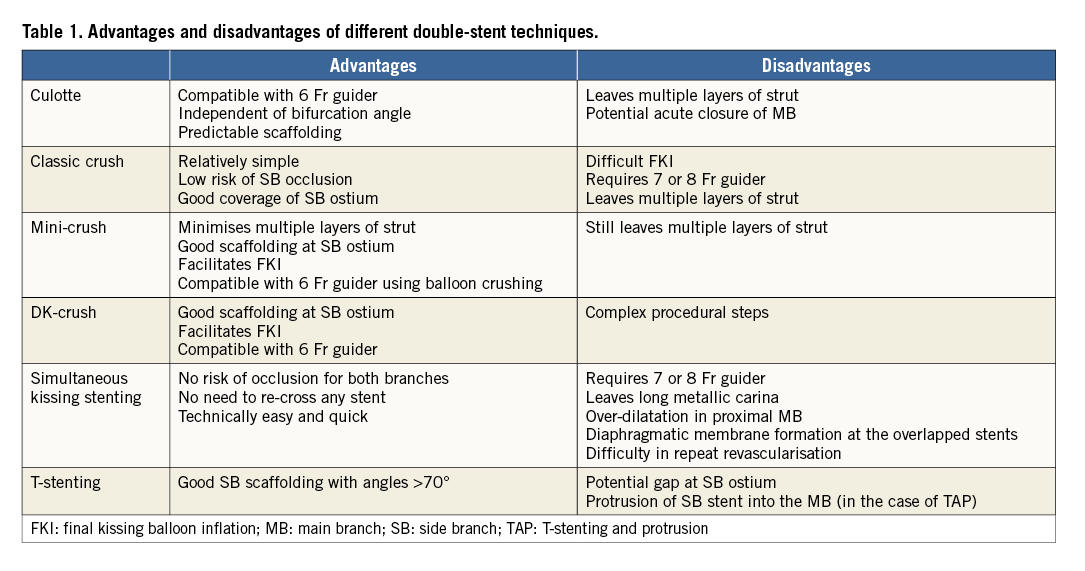

Strengths and weaknesses of various double-stent techniques

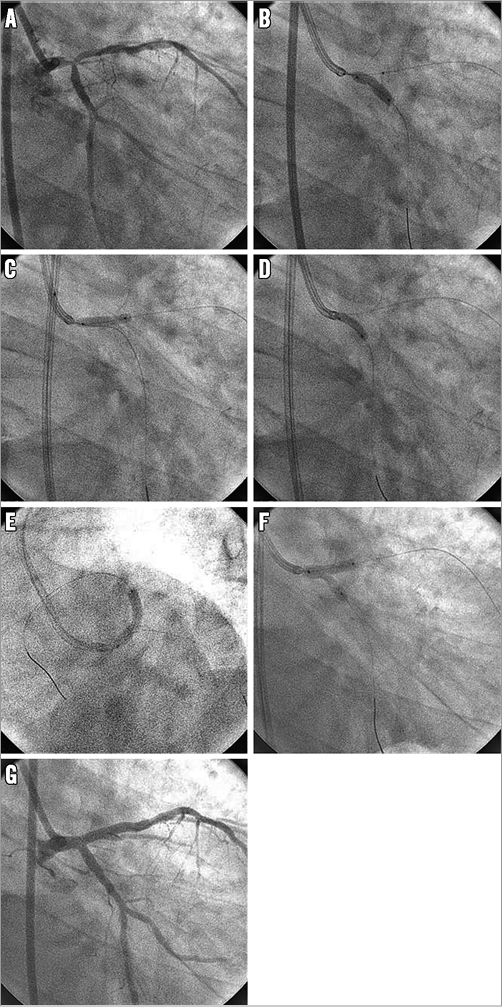

The advantages and disadvantages of each technique are listed in Table 1. The crush technique is a modified version of the T-stent technique, in which the MB stent crushes the SB stent against the MB wall. The classic crush technique is performed as the SB stent is retracted 4-5 mm into the MB lumen before being crushed by the MB stent. To overcome the weakness of T-stenting, which leaves unstented gaps at the SB ostium, the crush technique provides excellent coverage of the SB ostium. On the other hand, three layers of struts covering the SB ostium just after the MB stent make the final kissing balloon inflation (FKI) laborious and this is sometimes associated with unsatisfactory results. Therefore, as a variation of the crush technique, the mini-crush technique was recently developed, involving minimal (usually 1-2 mm) retraction of the SB stent into the MB before crushing. Moreover, by adopting the balloon crush, this technique enables optional balloon dilation of the crushed SB stent before MB stent implantation, reducing two layers of stent strut to be rewired for FKI to one layer. Ormiston et al showed minimised residual metallic stenosis at the SB ostium and facilitated FKI after the mini-crush technique13. In addition, to enhance stent apposition further and facilitate FKI, the double-kissing (DK) crush technique includes additional kissing balloon inflation between SB crushing and MB stenting. Moreover, since there is no need for the simultaneous introduction of two stents, the procedure can be performed with 6 Fr guidance. A randomised study on data from the DKCRUSH-III trial showed a superior angiographic result for the DK-crush technique compared to the culotte technique for LM bifurcation lesions14. The step-crush, which is also called the balloon-crush technique, also facilitates FKI and stent manipulation and has 6 Fr compatibility as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Left main bifurcation stenting with step-crush (balloon-crush) technique. A) Left main (LM) bifurcation lesions involving both the ostial left anterior descending artery (LAD) and the left circumflex artery (LCX). B) Stenting for proximal LCX (zotarolimus-eluting Resolute Integrity stent, 3.5×15 mm; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with a LAD balloon behind in the main branch (non-compliant balloon 3.5×15 mm). C) Crushing of an LCX stent using a LAD balloon. D) Rewiring and inflation of an LCX balloon (compliant balloon, 2.5×20 mm). E) Stenting for LM and LAD (zotarolimus-eluting Resolute Integrity stent, 3.5×30 mm). F) Rewiring and final kissing balloon inflation (non-compliant balloons, 4.0×15 mm for LAD and 3.5×15 mm for LCX). G) Final angiogram.

The culotte technique consists of sequential implantation of two stents into both branches, with the MB stent implanted through the SB stent and protruding into the MB lumen. Consequently, it leaves the proximal MB covered with two overlapping stents. This technique is suitable for all angles of bifurcation and provides good coverage of the SB ostium15,16. However, it may cause intraprocedural acute closure of the MB after SB stenting, which is catastrophic in PCI for distal LM disease. Another disadvantage is that, like the crush technique, it leaves double stent layers, potentially leading to delayed endothelialisation and subsequent stent thrombosis. Lastly, the distal MB stent at the ostial LAD can be underexpanded because it is positioned through the SB stent strut. To overcome the drawbacks of the culotte technique, the DK mini-culotte technique was also recently introduced, and its clinical benefit is being evaluated17. In this technique, the balloon catheter is placed in the MB before SB stenting to prepare acute closure of the MB. Moreover, kissing balloon inflation is performed before and after MB stenting.

The simultaneous kissing stent technique consists of the delivery and implantation of two stents together with a two-barrel metallic carina in the LM. The main advantage of this technique is that it guarantees the patency of both branches during the procedure and does not require rewiring for FKI. This technique is applicable in narrow angle bifurcations where the LM diameter is much bigger compared to that of the LAD and LCX. Nevertheless, this technique is now rarely used because of several concerns, e.g., difficulty in placing the stent proximal to the double barrel, formation of a new diaphragmatic membrane at follow-up, and difficulty in wiring in the case of restenosis18. However, its technical ease and rapidity make it an appropriate option for patients in highly unstable presentations, such as ST-elevation myocardial infarction involving the LM. In a case where the two stents just touch together not making a metallic carina of considerable length, this technique is called the V-stent technique. The V-stent technique is suitable for lesions which spare the LM shaft (Medina 0,1,1).

Few studies have reported stenting techniques for trifurcation LM stenosis. Recently, the long-term clinical outcomes of 84 patients with trifurcation LM stenosis from the Milan-New Tokyo registry were reported19. In that study, 13% of patients receiving the triple-stenting technique experienced a very high restenosis rate of 55%. Therefore, the triple-stent technique should be reserved as a bail-out strategy, considering the risk of stent distortion caused by this complex technique.

Procedural factors for good outcomes

Despite the unique strengths and weaknesses of each technique, none of the double-stent techniques has proven to be superior to the others. Although better outcomes were reported with the DK-crush technique than with the culotte technique in the previous DKCRUSH-III trial14, these results have not yet been validated in further research by other investigators. Considering the results of previous studies on non-LM bifurcation lesions20, no single double-stent technique is universally applicable to all LM bifurcation lesions. Instead, the outcomes of double-stent techniques may be related to procedural success and to optimisation of the method.

Several procedural factors can influence the clinical outcomes of stenting. FKI should be accompanied in all double-stent techniques to avoid incomplete apposition or underexpansion of stents13,21,22. IVUS is also useful to evaluate bifurcation lesions and to optimise stenting techniques. The cut-offs of IVUS-measured minimal stent areas to prevent in-stent restenosis were reported as approximately 5 mm2 for ostial LCX, 6 mm2 for ostial LAD, 7 mm2 for polygon of confluence, and 8 mm2 for LM23. A meta-analysis showed that IVUS guidance is likely to improve clinical outcomes24. Therefore, more emphasis should be placed on how to perform the optimal stenting procedure than on the actual double-stent technique that should be used.

Conclusions

Due to the large jeopardised area in the LCX territory, double stenting is still a viable treatment approach for LM bifurcation lesions in contrast to non-LM bifurcation lesions. When double stenting is chosen, attention should be paid to optimise the chosen technique. Meticulously performed FKI and IVUS guidance is helpful to achieve optimised procedural results and subsequently to improve clinical outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.