Recently, the results of the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial were published in the New England Journal of Medicine1. A group of high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) deemed non-surgical candidates were randomised to either transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) or standard medical therapy including balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV). The authors need to be congratulated on their excellent results. The one-year results showed a reduced rate of death to 30.7% in the TAVI group, compared to 50.7% in the standard therapy group. Safety assessment was however less in favour of the percutaneous technique, as 6.7% suffered a stroke or TIA 30 days within randomisation, compared to only 1.7% in the standard therapy patients (p=0.03). After one year, this difference was still significant (10.6% vs 4.5%, p=0.04).

Despite this increased incidence of thromboembolic events, the authors conclude that TAVI is the new golden standard for patients with severe AS who are too sick for surgery. However, in the spring of 2011, the trial will provide the long anticipated answers to whether randomisation to TAVI is superior to surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) in patients categorised as surgical candidates.

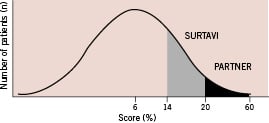

Since its introduction in 20022, TAVI has been used to treat high-risk or inoperable patients. In the PARTNER study as well, only high-risk patients were included having in the TAVI and standard therapy groups a mean Logistic EuroSCORE (LES) of 26.4% and 30.4%, respectively, and the Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) predicted risk of mortality scores of 11.2% and 12.1%, respectively. Other published data have also shown these high surgical risks in TAVI treated patients3,4. Bern and Rotterdam gathered data on 1,122 patients who underwent TAVI or AVR. In this cohort, the mean LES of patients treated with TAVI (n=114) or AVR (n=1,008) was 20.1%±13.4% and 9.1%±10.2%, respectively. Hence, the scores can be displayed in a distribution curve, with, in the far right, the group of patients treated with TAVI, similar to those in the PARTNER study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Expected EuroSCORE distribution of patients with AS, who undergo surgery (AVR or TAVI).

Now that a randomised study in high-risk patients has shown these promising results, the next step would be to consider TAVI in an intermediate risk group. European centres have implanted a total of 25,000 percutaneous valves. Over time, a broader spectrum of patients is being evaluated for TAVI, and more patients with lower scores are being treated. The upcoming prospective, multicentre, randomised controlled SURTAVI study will be evaluating the efficacy and safety of the Medtronic CoreValve System (Medtronic CoreValve, Irvine, CA, USA) compared to surgical AVR in patients with a lower surgical risk. Thus, these patients will be closer to the average AVR population (Figure 1).

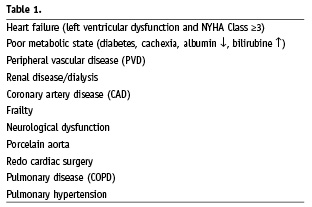

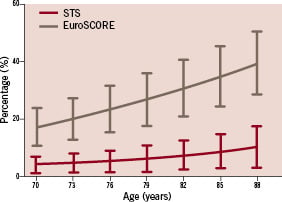

The identification of this patient group is however, easier said than done. An intermediate risk group could include patients between 70-74 years of age with ≥2 but ≤4 comorbid factors; 75-79 year-olds with ≥1 but ≤3 factors; and ≥80 years of age with ≤2 factors. If we convert these risk factors (Table 1) to corresponding STS score and EuroSCORE, this immediately shows the limitations of these scoring systems. The STS score ranges from 0.9% to 14.1%, while the EuroSCORE predicts mortality ranging from 9.1%-54.5% (Figure 2). Not only does EuroSCORE calculate scores many times higher than the STS score, the discrepancy is not consistent. This is caused by the incomparable magnitude in which comorbidities influence the score.

Figure 2. STS score and EuroSCORE range in a patient with two comorbidities.

One major shortcoming of both scores is the lack of entry fields. Both scores miss an entry for frailty and porcelain aorta. Other risk factors need to be entered in the STS score, but are not incorporated in the EuroSCORE, and vice versa. Therefore, a new score including all factors should be developed to identify which patients will benefit from TAVI or surgical AVR. This score should not only include hospital mortality, but also long-term benefit in terms of survival and quality of life. Registries and future trials should not only evaluate techniques, but also provide data that eventually can lead to the development of a new scoring system.