During chronic total occlusion (CTO) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), retrograde wire externalisation (RWE) is the standard technique after successful retrograde guidewire crossing. When RWE is unfeasible or undesirable, the tip-in and rendezvous techniques can be used1. In the tip-in technique, the retrograde wire is advanced into an antegrade microcatheter within the antegrade guide catheter. In the rendezvous technique, an antegrade wire is advanced into the retrograde microcatheter. The system is then converted to antegrade in both scenarios. We examined the frequency and outcomes of the tip-in and rendezvous techniques in a large, multicentre registry.

We analysed the baseline characteristics and procedural outcomes of 2,456 CTO PCIs with successful retrograde crossing, performed at 44 US and non-US centres between January 2012 and March 2023 in the PROGRESS-CTO (Prospective Global Registry for the Study of Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02061436) registry.

Technical success was defined as successful CTO revascularisation with <30% residual target lesion diameter stenosis and Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade 3 antegrade flow. Procedural success was defined as technical success without any in-hospital major adverse cardiac event (MACE). In-hospital MACE included death, myocardial infarction, urgent repeat target vessel revascularisation, tamponade requiring pericardiocentesis or surgery, and stroke prior to hospital discharge.

The tip-in and rendezvous techniques were utilised in 73 (3.0%) and RWE in 2,383 (97.0%) procedures. The clinical characteristics and the mean Japanese-CTO (J-CTO) (2.8±1.2 vs 3.0±1.1; p=0.18) and PROGRESS-CTO (1.4±1.0 vs 1.2±0.9; p=0.11) scores were similar between the two groups.

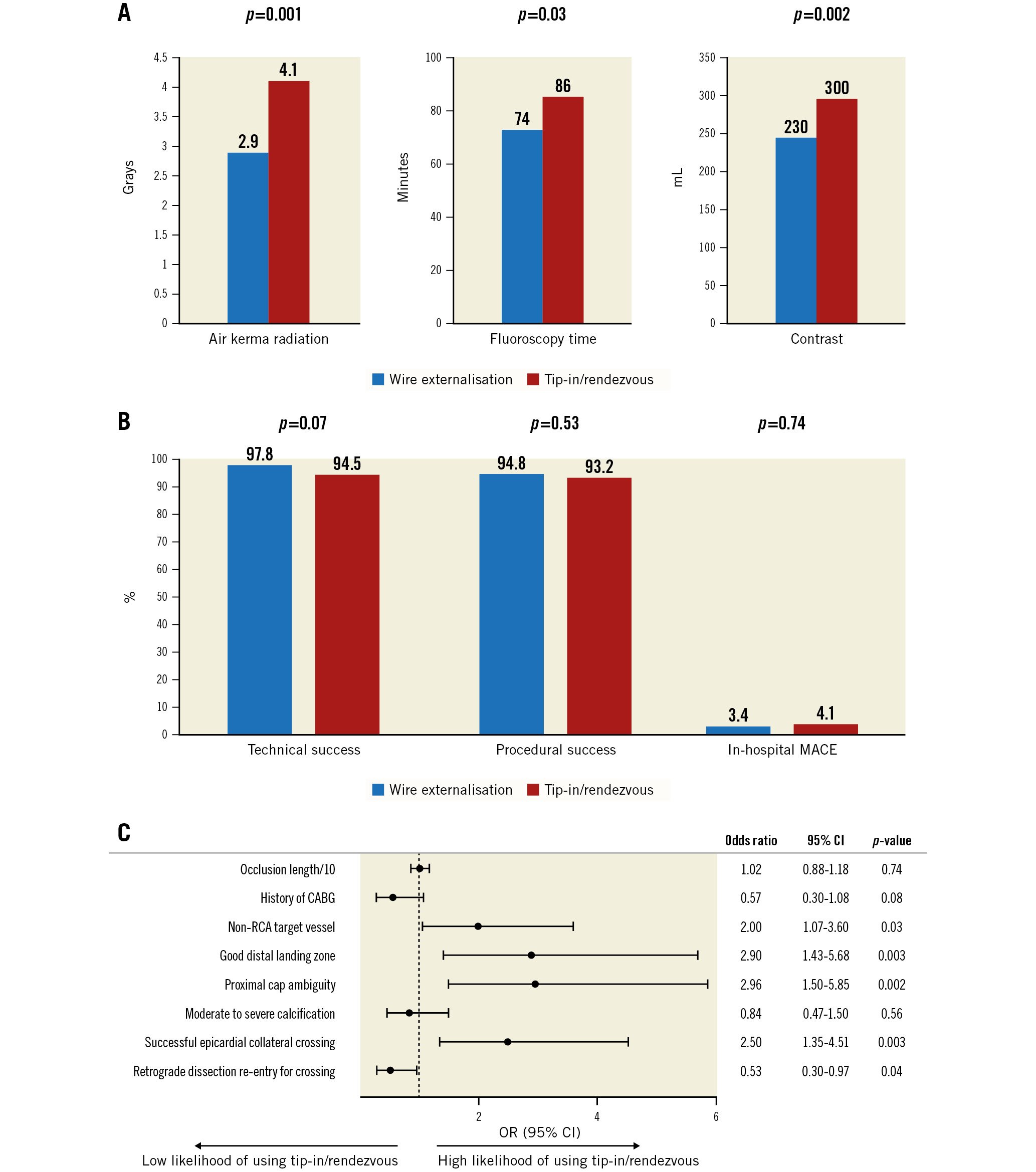

Successful retrograde epicardial collateral crossing (35.2% vs 18.1%; p<0.001) and retrograde true lumen crossing were higher (56.2% vs 33.5%; p<0.001) in the tip-in/rendezvous group. Procedures requiring tip-in/rendezvous were associated with worse procedural metrics (Figure 1A).

The microcatheter and wires most used for the tip-in/rendezvous techniques were the Finecross (Terumo) (23.2%) and polymer-jacketed wires (33.3%), respectively. The most common reasons for use of these techniques were inability of the retrograde microcatheter to reach the antegrade guide catheter (35.4%), operator preference (18.8%), use of epicardial collaterals (16.7%), severe stenosis distal to the target lesion or bifurcation stenting (12.5%) and avoidance of a second access with RWE through an ipsilateral collateral into a single guide (8.3%). The rendezvous technique was performed in 8.4% of the procedures, 4.2% within the CTO segment.

There were no significant differences in technical (94.5% vs 97.8%; p=0.07) or procedural (93.2% vs 94.8%; p=0.53) success and in-hospital MACE rates (4.1% vs 3.4%; p=0.74) between the tip-in/rendezvous and RWE groups (Figure 1B), even after propensity matching (odds ratio for technical success=0.41, 95% CI: 0.13-1.34; p=0.136; odds ratio for in-hospital MACE=1.58, 95% CI: 0.42-5.92; p=0.495).

On multivariable logistic regression, a non-right coronary artery (RCA) target vessel, a good distal landing zone, use of epicardial collaterals, and proximal cap ambiguity were independently associated with a higher likelihood of using the tip-in and rendezvous techniques over wire externalisation (Figure 1C).

The tip-in and rendezvous techniques can facilitate retrograde CTO PCI. Azzalini et al reported their use in 9% and 7% of ipsilateral (76% epicardial) retrograde procedures, respectively, reflecting the operators’ desire to avoid the haemodynamic strain and risks associated with epicardial crossing and convert the system to antegrade2. In our study, the use of epicardial channels was independently associated with the use of these techniques.

When CTO treatment involves distal vessel or bifurcation stenting, the tip-in/rendezvous technique can establish antegrade access to the target vessel or side branch distal to the distal cap, likely explaining the independent association of a non-RCA target vessel with a higher likelihood of utilising these techniques in our study.

When the retrograde microcatheter fails to cross the occluded segment, use of the tip-in technique can be advantageous. When the retrograde wire fails to cross the occlusion, the rendezvous technique can be performed within the CTO segment3. Nihei et al described 10 cases of successful retrograde crossing using intralesion tip-in/rendezvous techniques without performing reverse controlled antegrade and retrograde tracking4.

The tip-in/rendezvous techniques have worse procedural metrics, as many of these are performed after failed RWE. Nevertheless, the success and in-hospital MACE rates between the two groups were similar. Externalised wires offer superior support for the passage of coronary equipment, which is lost when the system is converted to antegrade.

Our study has limitations. PROGRESS-CTO is an observational registry without independent adjudication of clinical events or core laboratory angiographic assessment. The database did not capture whether RWE was attempted before using the tip-in/rendezvous techniques. Utilisation of these techniques is operator dependent; in our study, 3 centres performed 60.3% of all tip-in/rendezvous procedures.

The tip-in/rendezvous techniques are alternative strategies to RWE in retrograde CTO PCI and are associated with worse procedural metrics but similar technical and procedural success and in-hospital MACE.

Figure 1. Procedural outcomes and utilisation of the tip-in and rendezvous techniques. A) Procedures using tip-in/rendezvous required longer fluoroscopy time (86 [60, 118] vs 74 [54, 99] minutes; p=0.03) higher air kerma radiation dose (4.1 [2.4, 7.7] vs 2.9 [1.7, 4.8] Grays; p=0.001) and higher contrast volume (300 [185, 450] vs 230 [162, 320] mL; p=0.002). B) The tip-in/rendezvous techniques were associated with similar technical and procedural success and in-hospital MACE. C) Forest plot of multivariable analysis of variables associated with a higher likelihood of utilisation of the tip-in/rendezvous techniques. CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CI: confidence interval; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; OR: odds ratio; RCA: right coronary artery

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the philanthropic support of our generous anonymous donors and the philanthropic support of Drs Mary Ann and Donald A. Sens, Mrs Diane and Dr Cline Hickok, Mrs Wilma and Mr Dale Johnson, Mrs Charlotte and Mr Jerry Golinvaux Family Fund, the Roehl Family Foundation and the Joseph Durda Foundation. The generous gifts of these donors to the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation (MHIF) & Science Center for Coronary Artery Disease (CCAD) helped support this research project. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at the MHIF, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Conflict of interest statement

S.S. Allana is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Abiomed.N. Abi-Rafeh is a proctor and has received speaker honoraria from Boston Scientific and Shockwave Medical. K. Alaswad is a consultant and speaker for Boston Scientific, Abbott Cardiovascular, Teleflex, and Cardiovascular Systems, Inc. L. Azzalini has received consulting fees from Teleflex, Abiomed, GE HealthCare, Asahi Intecc, Philips, Abbott Vascular, Reflow Medical, and Cardiovascular Systems, Inc. J.W. Choi has received speaker honoraria from Shockwave Medical. R. Davies has received speaker honoraria from Abiomed, Asahi Intecc, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Siemens Healthineers, Shockwave Medical, and Teleflex; and is on the advisory boards for Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Rampart. A. ElGuindy has received consulting honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Asahi Intecc, and Terumo; and has received proctorship fees from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Asahi Intecc, and Terumo. D. Karmpaliotis has received honoraria from Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, and Abiomed; and equity from Saranas, Soundbite, and Traverse Vascular. F.A. Jaffer has done sponsored research for Canon, Siemens, Shockwave Medical, Teleflex, Mercator, Boston Scientific, HeartFlow, and Amarin; is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Siemens, Magenta Medical, International Medical Device Solutions, Asahi Intecc, Biotronik, Philips, Intravascular Imaging, and DurVena; has equity interest in Intravascular Imaging Inc, and DurVena; and has the right to receive royalities through Massachusetts General Hospital's licensing arrangements with Terumo, Canon, and Spectrawave. J.J. Khatri has received personal honoria for proctoring and speaking from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Terumo, and Shockwave Medical. P. Poommipanit is a consultant for Medtronic, Asahi Intecc, and Abbott Vascular. W. Nicholson is a proctor and is on the speakers’ bureau and advisory board for Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Asahi Intecc; he reports intellectual property with Vascular Solutions. W. Jaber has received consulting fees from Inari Medical and Medtronic. S. Rinfret is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Teleflex, Medtronic, Abbott, and Abiomed. E.S. Brilakis reports consulting/speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular, American Heart Association (Associate Editor of Circulation), Amgen, Asahi Intecc, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Innovations Foundation (Board of Directors), ControlRad, CSI, Elsevier, GE HealthCare, IMDS, InfraRedx, Medicure, Medtronic, Opsens, Siemens, and Teleflex; has received research support from Boston Scientific, GE HealthCare; is the owner of Hippocrates LLC; and is a shareholder in MHI Ventures, Cleerly Health, and Stallion Medical. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.