Abstract

Aims: In the elderly population, bare metal stents (BMS) are often preferred over drug-eluting stents (DES) because of the longer duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) associated with the latter. The SENIOR trial is designed to determine whether one of the latest generation of DES can reduce major cardiovascular events compared to BMS, despite a similar short DAPT duration.

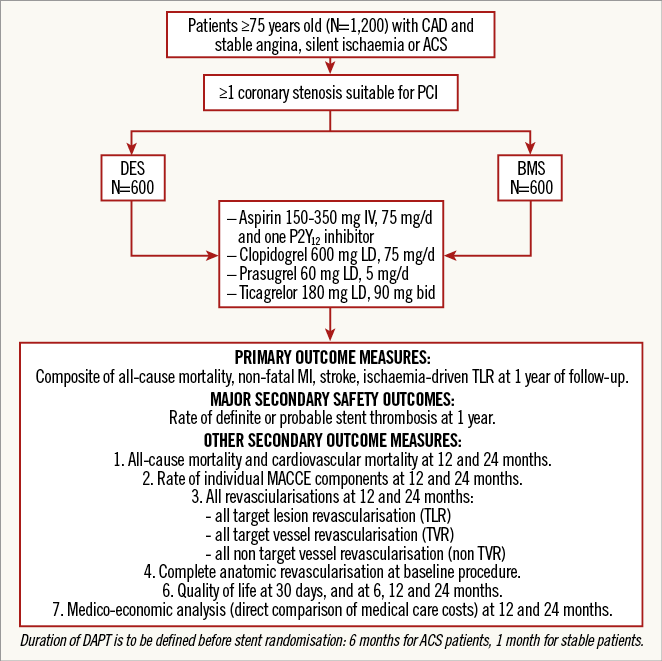

Methods and results: The SENIOR trial is a multicentre, single-blind, prospective, randomised trial comparing the latest generation DES (SYNERGY™ II; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) to BMS (Rebel™; Boston Scientific) in 1,200 patients ≥75 years old. DAPT will be given for one or six months according to clinical presentation, irrespective of stent type. The primary outcome is the composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke or ischaemia-driven target lesion revascularisation at one year. Secondary endpoints include the rate of major bleedings and the rate of stent thrombosis at one year.

Conclusions: This trial is designed to evaluate a new revascularisation strategy combining DES and short duration DAPT in elderly patients. It has the potential to decrease the need for target lesion revascularisation without a significant DAPT-related increase in bleeding compared to BMS.

Introduction

Despite age being a strong predictor of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)1,2, elderly patients have been largely excluded, under-represented or highly selected in randomised trials evaluating drug-eluting stents (DES). However, DES implantation in elderly patients could lead to a significant reduction in the rate of myocardial infarction (MI) and target vessel revascularisation compared to bare metal stent (BMS) implantation3.

New-generation DES have been demonstrated to be safer compared to first-generation DES4,5. In the Patient Related OuTcomes with Endeavor vs. Cypher stenting Trial (PROTECT), Camenzind et al reported a strong interaction between DES types and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) use, suggesting different vascular healing responses according to the type of DES6. More recently, in order to limit the potential long-term harm and toxicity associated with durable polymers7, DES with bioresorbable polymers have been developed8,9. Whether or not DES with a biodegradable polymer are safer than DES with a durable polymer is still a matter of debate10,11. However, Stefanini et al reported a lower risk of stent thrombosis and MI at four years with a biodegradable polymer DES in a pooled analysis including 4,062 patients12.

There is emerging evidence that reducing the duration of DAPT together with new-generation DES could represent a safe strategy. This might be particularly relevant for patients ≥75 years old, to reverse the unfavourable risk/benefit ratio associated with earlier-generation DES and long DAPT. Despite European Society of Cardiology and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines recommending 12 months of DAPT13-15, the optimal duration of DAPT after DES implantation remains largely unknown, particularly in patients ≥75 years old. Bleeding risk is higher in elderly compared to younger patients16, and is further increased with longer DAPT17-19 without clear reduction in stent thrombosis in several studies17,19,20. The potential impact of bleeding complications may explain why cardiologists are often reluctant to expose patients ≥75 years old to prolonged DAPT and why BMS are often preferred for PCI in these patients. Indeed, in a very recent registry from two reputable European centres, only about one out of four consecutive elderly patients undergoing PCI received at least one DES21.

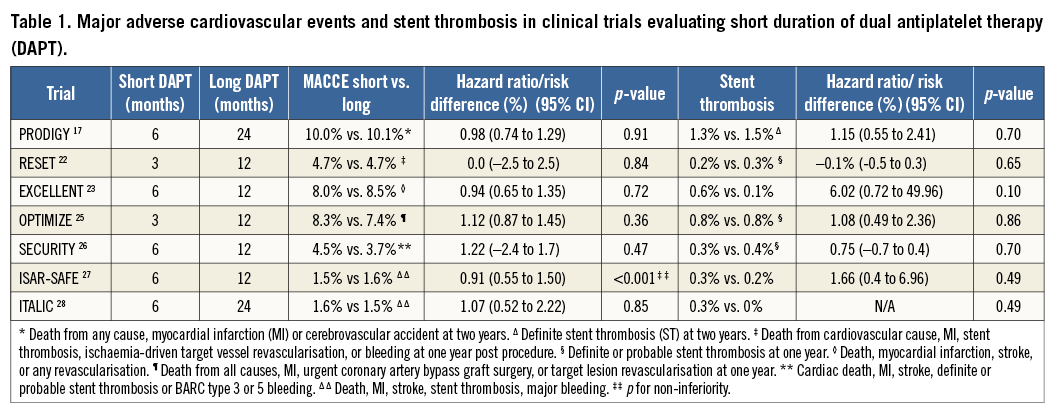

Several trials have reported similar efficacy and safety with short vs. long DAPT duration after PCI (Table 1). Three months of DAPT was non-inferior to 12 months of DAPT with respect to the occurrence of stent thrombosis or MACCE in the RESET (REal Safety and Efficacy of three-month dual antiplatelet Therapy following Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent implantation) trial22. MACCE at 12 months were non-inferior after six months vs. 12 months of DAPT (4.8% vs. 4.3%, p<0.001) in the EXCELLENT (Efficacy of XIENCE/Promus versus Cypher to rEduce Late Loss after stENTing) trial23. DAPT beyond 12 months was not more effective than aspirin alone in reducing the rate of MI and cardiac death in 2,701 patients treated with DES (HR 1.65, 95% CI: 0.80-3.36, p=0.17)24. In the PROlonging Dual antiplatelet treatment after Grading stent-induced Intimal hyperplasia studY (PRODIGY), patients receiving clopidogrel for six vs. 24 months had a similar rate of ischaemic events and stent thrombosis at two years17. Furthermore, in 3,119 patients treated with zotarolimus DES, the rates of death, MI, stroke and major bleeding at one year were similar with three months or 12 months of clopidogrel25. More recently, the SECURITY (Second Generation Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation Followed by Six- Versus Twelve-Months Dual Antiplatelet Therapy) trial26 and the ISAR-SAFE (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Safety And EFficacy of six months Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After drug-Eluting Stenting) trial27 reported similar rates of MACCE in patients with 12 months of DAPT compared to six months only (3.7% vs. 4.5%; difference 0.8%; 95% CI: –2.4-1.7; p=0.469, and 1.5% vs. 1.6%; HR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.55-1.50; pforsuperiority=0.70, respectively). Similarly, in the ITALIC plus (Is There A LIfe for DES after discontinuation of Clopidogrel) trial, the 2,031 patients treated with new-generation DES (XIENCE V®; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) had a similar rate of MACCE (death MI, stroke, TVR, major bleeding) whether they were treated with clopidogrel for six or 24 months (1.6% vs. 1.5%; HR 1.07, 95% CI: 0.52-2.22; p=0.85)28.

Registry data have shown increased one-year stent thrombosis rates after DAPT discontinuation within 30 days post PCI but not after one month (3.6% vs. 0.1%, log-rank p<0.001). DAPT interruption >1-12 months was provocatively associated with a lower rate of stent thrombosis compared to patients with no DAPT interruption within a year (0.1% vs. 0.8%, log-rank p<0.001)29. In a real-world registry, Mehran et al reported that thrombotic events after PCI largely occur while patients are still on DAPT, with an early risk of events due to disruption, irrespective of stent type (DES or BMS)20.

Finally, extending the duration of DAPT was not associated with a reduction in all-cause death (OR [95% CI] 1.15 [0.85-1.54], p=0.36), MI (OR 0.95 [0.66-1.36], p=0.77), stent thrombosis (OR 0.88 [0.43-1.81], p=0.73), or cerebrovascular events (OR 1.51 [0.92-2.47], p=0.10) in a meta-analysis including 8,231 patients18.

Recently, in the large Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT) study, patients treated with 30 months of DAPT exhibited a substantial reduction of stent thrombosis (0.4% vs. 1.4%; HR 0.29, 95% CI: 0.17-0.48; p<0.001) and MACCE (4.3% vs. 5.9%; HR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.59-0.85; p<0.001), associated with a higher all-cause mortality (2.0% vs. 1.5%; HR 1.36, 95% CI: 1.00 -1.85; p=0.05) and increased rates of severe or moderate bleedings (2.5% vs. 1.6%; HR 1.61, 95% CI: 1.21 to 2.16; p=0.001) compared to patients treated with only 12 months of thienopyridine30.

However, only selected patients were included in the trial, since investigators randomised patients who had already safely completed twelve months of DAPT after DES implantation. This represents a significant selection bias and implies that the DAPT results are only applicable to a selected population with global low ischaemic as well as bleeding risks. In addition, a large number of the patients were treated with first-generation DES associated with known delayed vascular healing, pro-inflammatory polymer or limited antirestenotic effect. In subgroup analysis, the effect of prolonged DAPT on MACCE was not similar among the different DES subtypes (p for heterogeneity=0.048)30.

More recently, the ZEUS trial (Zotarolimus-eluting Endeavor Sprint Stent in Uncertain DES Candidates) used a different approach to tackle the issue of efficacy versus safety in patients at risk for bleeding and/or thrombosis. This trial tested a zotarolimus-eluting stent (ZES) with an ultra-fast drug-eluting profile, followed by a variable DAPT duration based on patient comorbidities. The study demonstrated that ZES combined with an abbreviated and tailored DAPT regimen resulted in a lower risk of one-year MACCE in these uncertain candidates for DES implantation31. Nevertheless, these ZES are associated with a less powerful inhibition of neointima hyperplasia compared with the latest generation, slower eluting DES31. Altogether, the improved safety of new-generation DES and the lack of strong evidence supporting prolonged DAPT in the elderly population clearly support the need for a dedicated trial assessing the balance of efficacy and safety in patients ≥75 years old treated with PCI.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

A total of 1,200 subjects will be enrolled in the SENIOR (SYNERGY II Everolimus elutiNg stent In patients Older than 75 years undergoing coronary Revascularisation associated with a short dual antiplatelet therapy) trial, a prospective, single-blind, randomised multicentre trial registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02099617. The first patient was included on 25 May 2014.

OBJECTIVES

The primary objective of this superiority study is to assess the effectiveness and safety of new-generation DES (SYNERGY™ II; Boston Scientific), compared with BMS (Omega™ or Rebel; Boston Scientific), in patients ≥75 years old in preventing the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke and ischaemia-driven TLR at one year.

The secondary objectives are to assess the safety of PCI with DES versus BMS with identical duration of DAPT with respect to the rate of definite and probable stent thrombosis (Academic Research Consortium definition) at one year32.

Additional secondary outcome measures include all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, MI (periprocedural, spontaneous, Q-wave and non-Q-wave)33, stroke (all, ischaemic, and haemorrhagic) and all revascularisations (ischaemia-driven and non-ischaemia-driven) at 12 and 24 months. In addition, bleeding complications type 2, 3, and 5 according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium34 will be evaluated at one year.

Quality of life will be measured at 30 days post-procedure and at six, 12 and 24 months, and economic evaluation including direct comparison of medical care costs will be calculated at 12 and 24 months. Final cost-effectiveness will be assessed by the incremental cost per quality-adjusted year of life at two years.

DEFINITIONS

All-cause mortality is defined as any cause of death from inclusion until latest follow-up. Acute MI is defined by the evidence of myocardial necrosis in a clinical setting consistent with acute myocardial ischaemia according to the third universal definition of myocardial infarction33. Stroke is defined as appearance of a new focal neurologic deficit, with symptoms lasting less or more than 24 hours. Confirmation of the diagnosis with computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging will be used to differentiate between haemorrhagic and ischaemic strokes. All reported focal neurologic deficits reported during the study will be adjudicated. Ischaemia-driven target lesion revascularisation (TLR) is defined as any TLR for myocardial ischaemia (clinical evaluation or non-invasive assessment) under optimal medical treatment. All clinical events reported as being part of the primary endpoint, bleeding complication, or stent thrombosis will be reviewed by a dedicated, independent, clinical endpoint committee, unaware of the patient’s treatment group.

PATIENT POPULATION

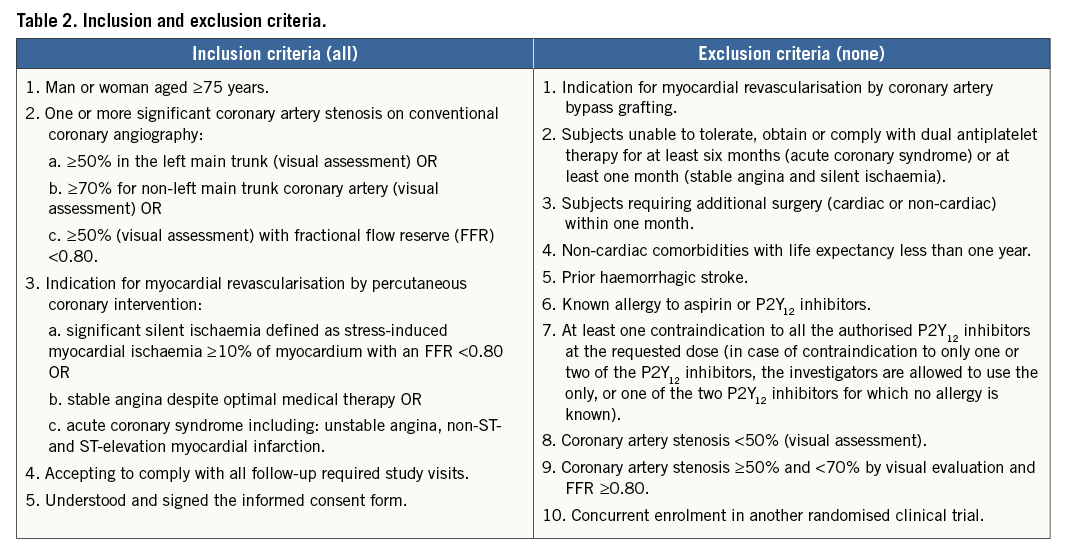

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Table 2. Recruitment flow is summarised in Figure 1. The steps in determining trial eligibility and obtaining informed consent are designed to mirror daily clinical practice closely in order to optimise recruitment.

Figure 1. SENIOR study design.

Consecutive subjects above 75 years of age in whom revascularisation by PCI of at least one coronary artery stenosis with visually assessed diameter stenosis ≥70% (≥50% in the left main) will be identified and screened for study eligibility. Subjects eligible for enrolment as per the general inclusion and exclusion criteria will be asked to sign an informed consent for the randomised trial.

INFORMED CONSENT

All subjects must provide informed consent in accordance with the local institutional review board (IRB)/ethics committee (EC), using an IRB/EC-approved informed consent form. Final eligibility for the trial will be confirmed based on the pre-intervention angiography. Local ethics committee approval was obtained on 16 April 2014 (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France III: 2014-A00281-46).

RANDOMISATION

Randomisation is carried out through a web-based system available 24 hours per day, all year round, and maintained by a data coordinating centre (Cardiovascular European Research Center, CERC, Massy, France).

The choice of antiplatelet agent and duration of DAPT are stratified upfront and are required to be entered in the Interactive Web Response System (IWRS) at randomisation, to avoid inequality between the two groups based on an unblinded physician’s decision.

MEASUREMENTS

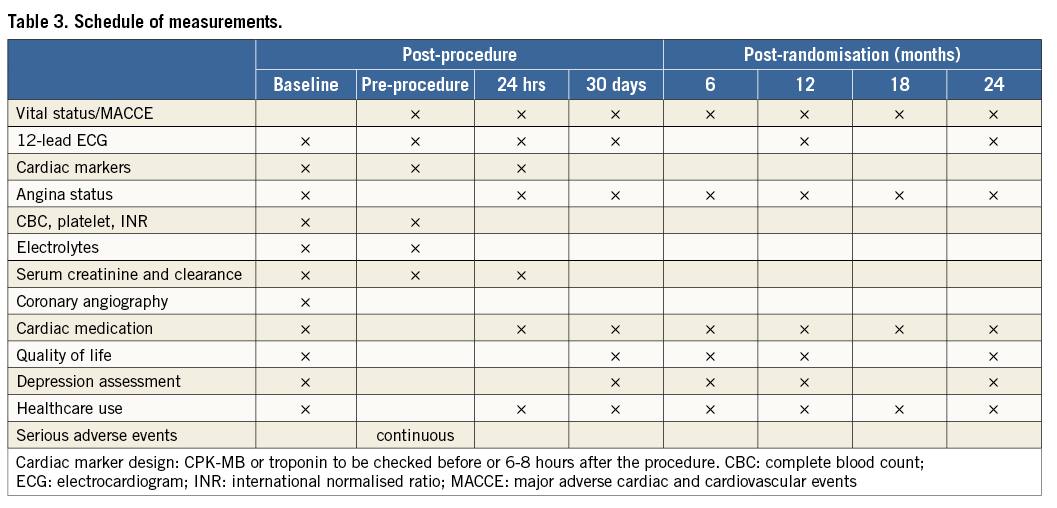

Table 3 summarises the schedule of measurements at 24 hours, 30 days and 180 days post procedure and annually thereafter for the duration of the study. In addition, telephone interviews will be conducted semi-annually to control vital status and identify intervening MACCE since the last in-hospital visit. Quality of life and depression data will also be collected at six and 12 months in the hospital.

REVASCULARISATION PROCEDURE

The transradial approach is recommended in experienced centres. The choice of guiding catheters, guidewires, predilatation, atherectomy devices, post-dilatation, and intracoronary imaging system is left to the investigator’s discretion. A final inflation using non-compliant balloons is recommended. The final objective is to obtain a <20% residual stenosis with a TIMI grade 3 distal flow without the loss of any side branch ≥2.0 mm in diameter. Only one type of stent is allowed in a patient during the index procedure, should he receive >1 stent. The randomisation process will determine which stent is allocated for any patient. In case of a staged procedure, PCI will be performed within a month after inclusion with the same study stent(s).

ANTITHROMBOTIC REGIMEN

Antithrombotic regimens in the cathlab, including unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin and bivalirudin are left to the physician’s discretion. DAPT duration will be one month after PCI for stable angina and silent ischaemia, and six months after PCI for acute coronary syndromes, irrespective of the type of stent. Aspirin will be given at a loading dose of 150-300 mg (orally) or 80-150 mg (intravenously) and at an oral maintenance dose of 75-100 mg daily, indefinitely. The P2Y12 inhibitors added to aspirin before or immediately after PCI could be either clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose and 75 mg/d), prasugrel (60 mg loading dose and 5 mg/d orally, half the maintenance dose given to <75-year-old patients) or ticagrelor (180 mg loading dose and 90 mg/bid orally). In case of a staged procedure, the duration of DAPT will be six months from the index procedure in patients with acute coronary syndrome at baseline or one month starting from the final PCI in patients with stable or silent ischaemia at baseline.

SAMPLE SIZE

The study is powered to test the superiority of DES with a relative 25% reduction in the primary endpoint compared to BMS. Assuming a primary endpoint event rate of 31% for BMS at one year (interpolated from the most contemporary and accurate references)14-17, a minimum time to follow-up of one year and a constant dropout rate yielding 15% lost to follow-up at one year, then a sample size population of 560 subjects per arm will provide 80% power to demonstrate superiority using a chi-square test (two-sided alpha=0.05) comparing the event rates at one year from the Kaplan-Meier curves. A total of 1,200 patients (600 in each arm) will be randomised. The sample size calculation was performed in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) using 10,000 simulations. Results from individual or secondary endpoints will only be considered to be hypothesis-generating.

QUALITY OF LIFE, AND DEPRESSION ANALYSIS

Quality of life will be assessed using the SF-12v235 and the EuroQol-5D36 self-administered questionnaires. These questionnaires have been validated in populations with coronary artery disease37. Quality-adjusted survival for each treatment group is estimated on the basis of observed clinical outcomes (survival) and country-specific utility weights.

Depression state will be assessed with the short version of the Geriatric Depression Scale used extensively in the elderly38.

COST-EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS

Medical care costs for the initial hospitalisation and for the one- and two-year follow-up periods will be assessed by a combination of “bottom-up” and “top-down” methods using patient-level detailed resource utilisation from the CRF, and DRG-specific costs from the national hospital activity-based costing study.

CARDIAC CATHETERISATION LABORATORY COSTS

Detailed resource use will be recorded for each procedure, and the cost of each item estimated on the basis of the most recent hospital acquisition cost for the item. Costs of additional disposable equipment, overheads, and depreciation for the cardiac catheterisation laboratory will be estimated from the DRG-specific average cost per procedure39.

OTHER HOSPITAL COSTS

All other hospital costs will be determined by using the national cost schedules, which provide itemised DRG-specific costs on a yearly basis. Hospital costs will be determined by multiplying the per diem itemised hospital costs (excluding procedural costs) by the actual length of stay of each patient in the trial. The most recent cost study available will be used.

OTHER COSTS

Outpatient services will be assessed by patient self-report of medication and service utilisation, and their costs will be estimated from the most recent national cost schedules.

OUTCOMES

Since the primary endpoint is a reduction in MACCE, the primary endpoint for the cost-effectiveness analysis is the incremental cost per event avoided by DES compared with BMS. This disease-specific cost-effectiveness ratio will be calculated by dividing the difference in mean one-year and two-year medical care costs for the two treatment groups by the difference in event rates over the same time frame. Final cost-effectiveness will be assessed for cost per quality-adjusted year of life gained at two years.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All primary analyses will be carried out using the intention-to-treat principle. The rates of the primary endpoint at one year in both groups will be determined from a Kaplan-Meier curve and compared by means of a chi-square test. In addition, a relative risk estimate with a 95% confidence interval will be provided. The rates of definite and probable stent thrombosis at one year will be analysed similarly. Cost data will be reported as both mean and median values and compared by t-tests. To estimate the uncertainty surrounding the cost-utility ratio, we will calculate bias-corrected CIs by the bootstrap method using 1,000 repeated samplings of the study population. All statistical analyses will be described in a statistical analysis plan, which will be finalised before the end of the study.

Limitations

The design of the SENIOR trial will only allow definite conclusions with regard to the primary combined endpoint, in view of the planned sample size. Given the expected relative scarcity of stent thrombosis and major bleeding complications, as well as all-cause mortality, dedicated trials in much larger populations of elderly patients will be needed to address the safety/benefit ratio of combining DES and short DAPT duration in these high-risk patients.

Conclusions

The SENIOR trial is designed to compare a new-generation DES with standard BMS in elderly patients receiving a similarly short duration of DAPT. A strategy combining the efficacy of this latest generation of DES to reduce ischaemia-driven revascularisations and re-hospitalisations with the safety of a short duration of DAPT could be of particular benefit in a high bleeding risk population such as the elderly.

| Impact on daily practice Improved outcomes associated with newer-generation stents without increased bleeding risk may alter the unfavourable risk/benefit ratio associated with first-generation DES and thus modify PCI strategies in elderly patients with coronary artery disease. |

Acknowledgements

Clinical trial operational management of the study is performed by CERC.

Funding

The study is funded by an unrestricted educational grant through the Investigator Research Program, from Boston Scientific.

Conflict of interest statement

O. Varenne has received speaker fees from Boston Scientific and Abbott Vascular. T. Cuisset has received consulting or speaker fees from Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards, Eli Lilly, Hexacath, Iroko Cardio, Medtronic, Servier and Terumo. M. Sabaté has received consulting fees from Abbott Vascular. O. Hanon has received consulting or speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer, Boston Scientific, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and Vifor. I. Durand-Zaleski has received consulting or speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Sanofi, Janssen, BMS, Pfizer, and Medtronic. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.