Introduction

We are frequently confronted with a request to consider valve implantation in patients who will not live to see a clear overall improvement of their prognosis. The decision to withhold interventional treatment often does not come easily and should be made following ethically informed protocols and guidance.

We will review the various patient groups with reduced life expectancy, highlight the recommended decision pathways, refer to the available experience and guidelines, and discuss the management choices for this difficult cohort of patients.

Patient groups with limited life expectancy

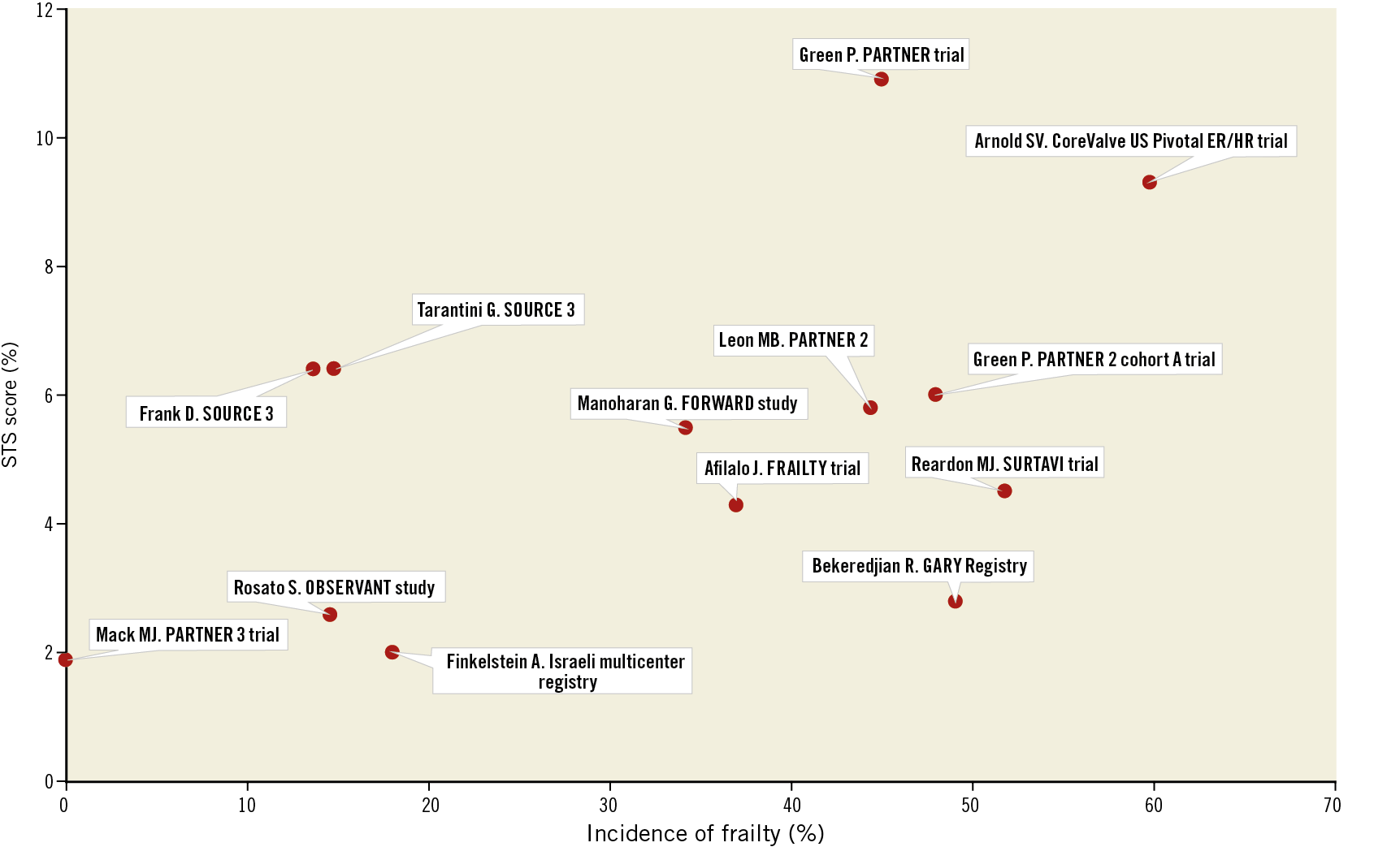

Many patients presenting to the heart valve service are elderly and frail, often with reduced mobility and conditions (cardiac and non-cardiac) which by themselves lead to reduced exercise capacity, breathlessness and volume overload. The most frequent comorbidities in elderly patients with aortic stenosis (AS) are arrhythmia, ischaemic heart and chronic lung disease, renal impairment, heart failure, dementia and frailty. Patients with comorbidities have a high mortality during follow-up after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), but they may still derive a substantial benefit in terms of quality of life1. Frailty is difficult to define and quantify, and the prevalence of frailty in reported cohorts shows a large variation2 (Figure 1). In the PARTNER A trial, patients with a prohibitive surgical risk and symptomatic AS were enrolled. In these patients, life expectancy was limited by the disease itself as well as comorbidities. While TAVI improved the prognosis3, mortality was high in treated patients, presumably due to the presence of comorbidities and frailty.

Figure 1. Variation of the incidence of frailty in reported patient cohorts. Reproduced with permission from Petronio et al2.

A separate group of patients is defined by symptomatic severe AS, a life-threatening condition that impacts on their prognosis independently. Not infrequently we see patients with newly detected malignancies in the course of the diagnostic workup for TAVI. Also, we see patients referred from oncologists. These patients, after having been diagnosed with cancer, are found to have severe AS with or without symptoms. In these patients, who usually have a high functional level, the decision for treatment is based on the expected gain from treatment of both AS and the underlying health condition.

Decision process

It has previously been suggested that the indication for TAVI should be guided by: 1) clinical risk stratification; 2) geriatric risk stratification; 3) anticipated clinical benefit; and 4) assessment of patient goals and preferences4. For patients with limited life expectancy, the focus should be on the anticipated clinical benefit and patient preferences.

The relevance of the AS itself for prognosis and symptoms has to be clearly established. In patients with life-threatening non-cardiac comorbidities, a multidisciplinary discussion should identify individual prognostic factors. Of importance is the impact of TAVI on therapeutic options that may have a prognostic benefit. A typical example here would be cancer patients who would not be accepted for cancer surgery without correction of their severe AS.

Communication between specialities needs to be direct and focused on the individual patient, with a clear outline of the treatment options, expected consequences and associated risks. While it can often be difficult to estimate the life expectancy, it is important to document the best possible prediction. Therefore, it is essential to get a clear prognostic assessment from the oncology team before treatment decisions are made. Equally, the cumulative risks of all treatments should be considered.

In patients with a high frailty score and a limited chance of recovery to a good quality of life, the decision for palliative therapy is appropriate. The same is true for patients with an adverse short-term outlook, even following successful TAVI.

The scope of patients who can undergo TAVI is defined by generally accepted indications, local protocols and health economic considerations specific to the healthcare environment.

The threshold generally applied is 12 months expected survival. This is arbitrary and should be adjusted in individual cases. If TAVI has the potential for a substantial improvement in the quality of the remaining life, then patients with a shorter prognosis should be treated.

If the patient has a very low quality of life and TAVI is not likely to change symptoms in a relevant way, then even in light of a better prognosis the decision for palliative medical treatment can be appropriate.

A decision between palliation and intervention needs to take into account patient goals and preference. All considerations and outcomes of multidisciplinary team discussions need to be clearly communicated to the patient and the family involved.

Guidelines

The most recent ESC guidelines5 give a Class III recommendation: “Intervention should not be performed in patients with severe comorbidities when the intervention is unlikely to improve quality of life or survival”. They also give the 12-month survival as the arbitrary basis for the indication to intervene: “Early therapy should be strongly recommended in all symptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis because of their dismal spontaneous prognosis. The only exceptions are patients with severe comorbidities indicating a survival of <1 year and patients in whom severe comorbidities or their general condition at an advanced age make it unlikely that the intervention will improve quality of life or survival”. A gap in evidence and guidance is recognised, referring to missing valid criteria to decline treatment: “Criteria for when TAVI should no longer be performed since it would be futile need to be further defined”. The central role of the Heart Team in decision making and the involvement of patient and family are emphasised.

Interventional considerations

The role of balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) in the treatment of symptomatic patients with severe AS and comorbidities is controversial. The practice varies considerably with limited series reporting the outcome in contemporary practice. In PARTNER A, BAV was accepted in the palliative treatment arm and did not affect the survival in this group3. However, BAV can lead to acute improvement and help with stabilisation, reducing the hospital stay and allowing a safe discharge in patients presenting with acute decompensation. It can also be considered in patients with reduced long-term prognosis as a palliative measure to reduce the symptomatic burden. The benefit of BAV may be short-lived. In our experience, TAVI is more predictable and can be safely offered in the vast majority of patients where treatment of AS is indicated.

The choice between surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and TAVI may be affected by the presence of a terminal illness. The durability of the valve implant is of no relevance in patients with a predicted survival of even 5-10 years. Hence, in this patient group the choice of TAVI over the more invasive SAVR appears to be in the patient’s best interest.

Conclusion

Decision making in patients with symptomatic severe AS and reduced life expectancy can prove challenging. A full understanding of the prognostic and symptomatic status is essential and often requires multidisciplinary communication. The focus of the decision lies in achieving what is in the individual patient’s best interest, taking into account the estimated procedural risk, symptomatic benefit and patient goals. The quality of life in the remaining lifetime of the patient is the metric we should apply, knowing that this is a parameter much more difficult to quantify than mere survival.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Baumbach reports personal fees from MicroPort, SINOMED, Abbott Vascular and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. M. Mullen reports personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Edwards, outside the submitted work.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.